It is important to understand the connection between using mixture models for classification and other procedures that are commonly used out there for classification. One example of those procedures that has a strong connection is linear discriminant analysis. And also, by the way, quadratic discriminant analysis. But let’s start with linear discriminant analysis.

And to illustrate that connection, let’s start with a very simple mixture model.

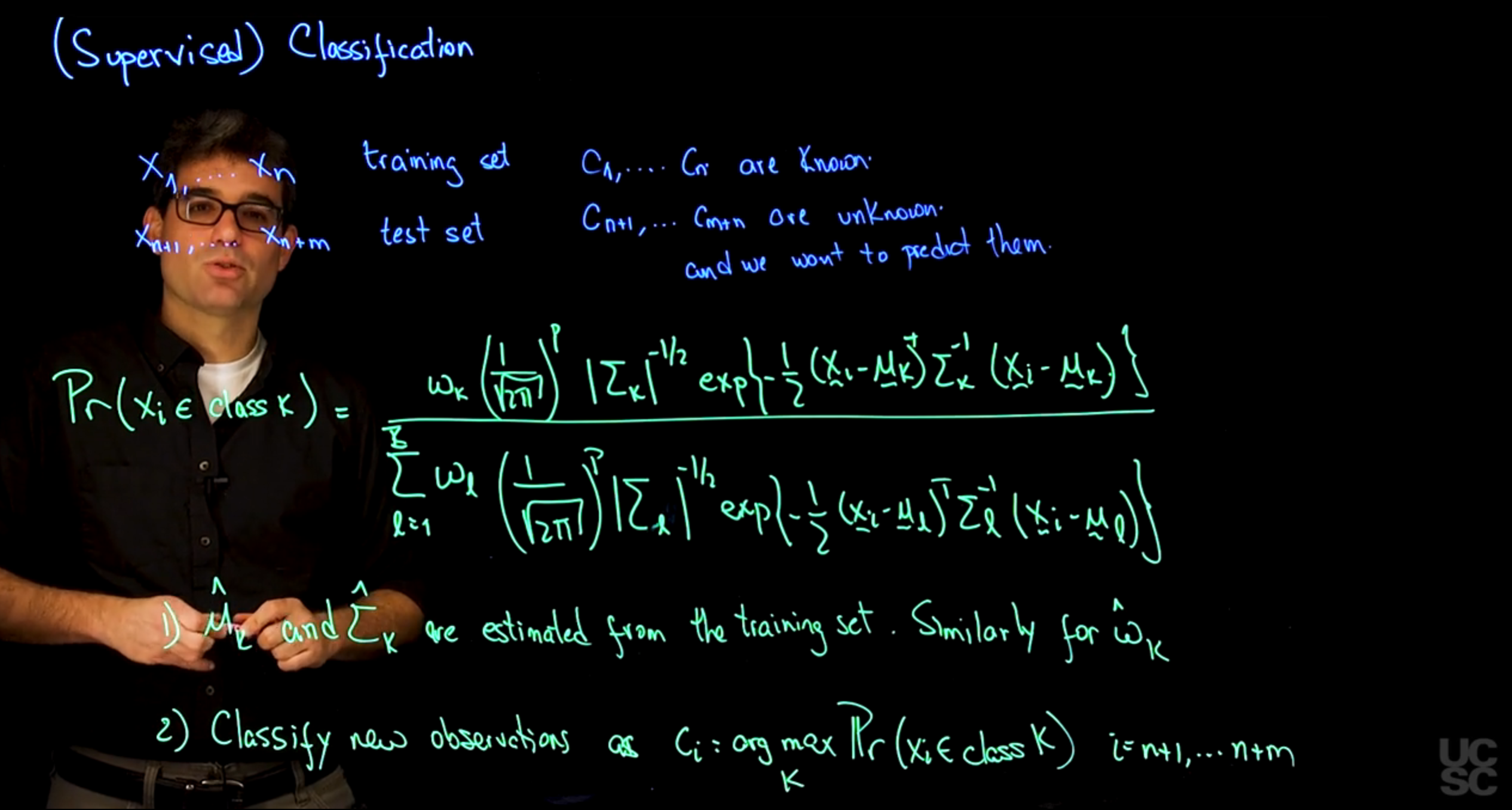

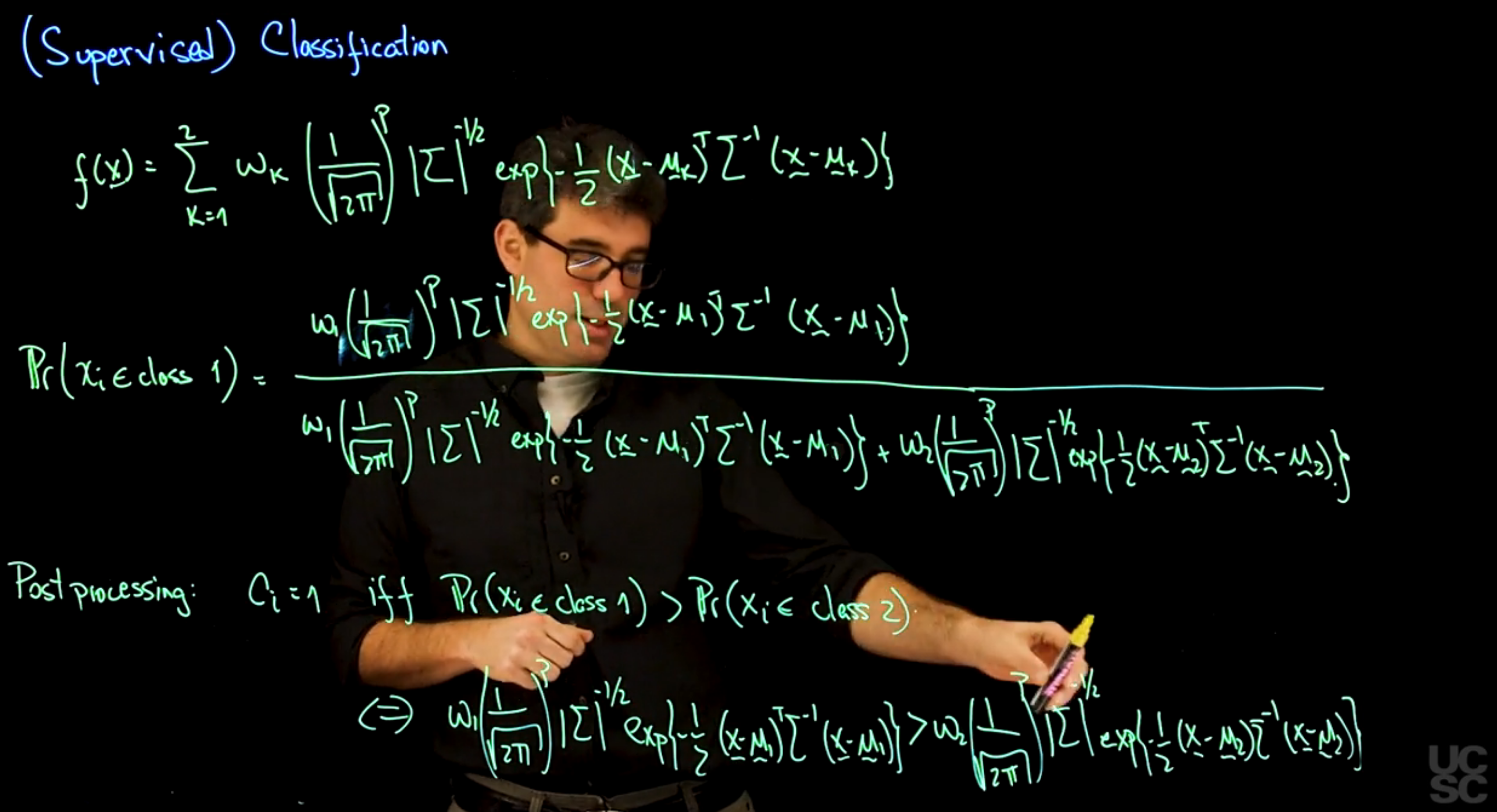

So let’s start with a mixture model of the form, f(x) = the sum from 1 to 2. So I’m going to be working only with two components of omega k, 1 over the square root 2pi to the p determinant of sigma to the -1 half, x- 1 half, x, mu sub k, transpose sigma inverse, x- mu sub k. So this is two-component mixture with locations bearing with a component, but the same variance-covariance matrix for the two components that I have in the mixture.

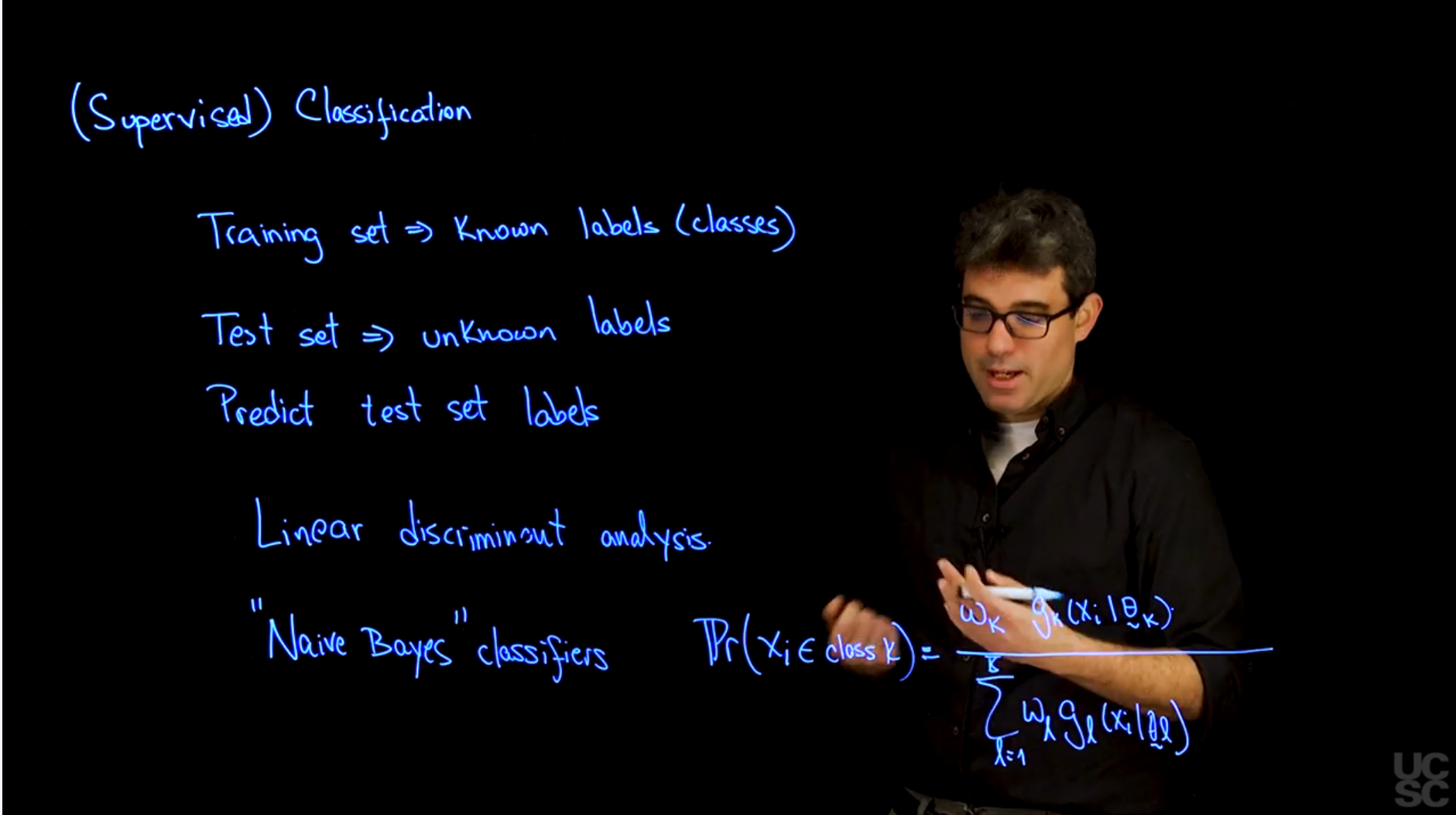

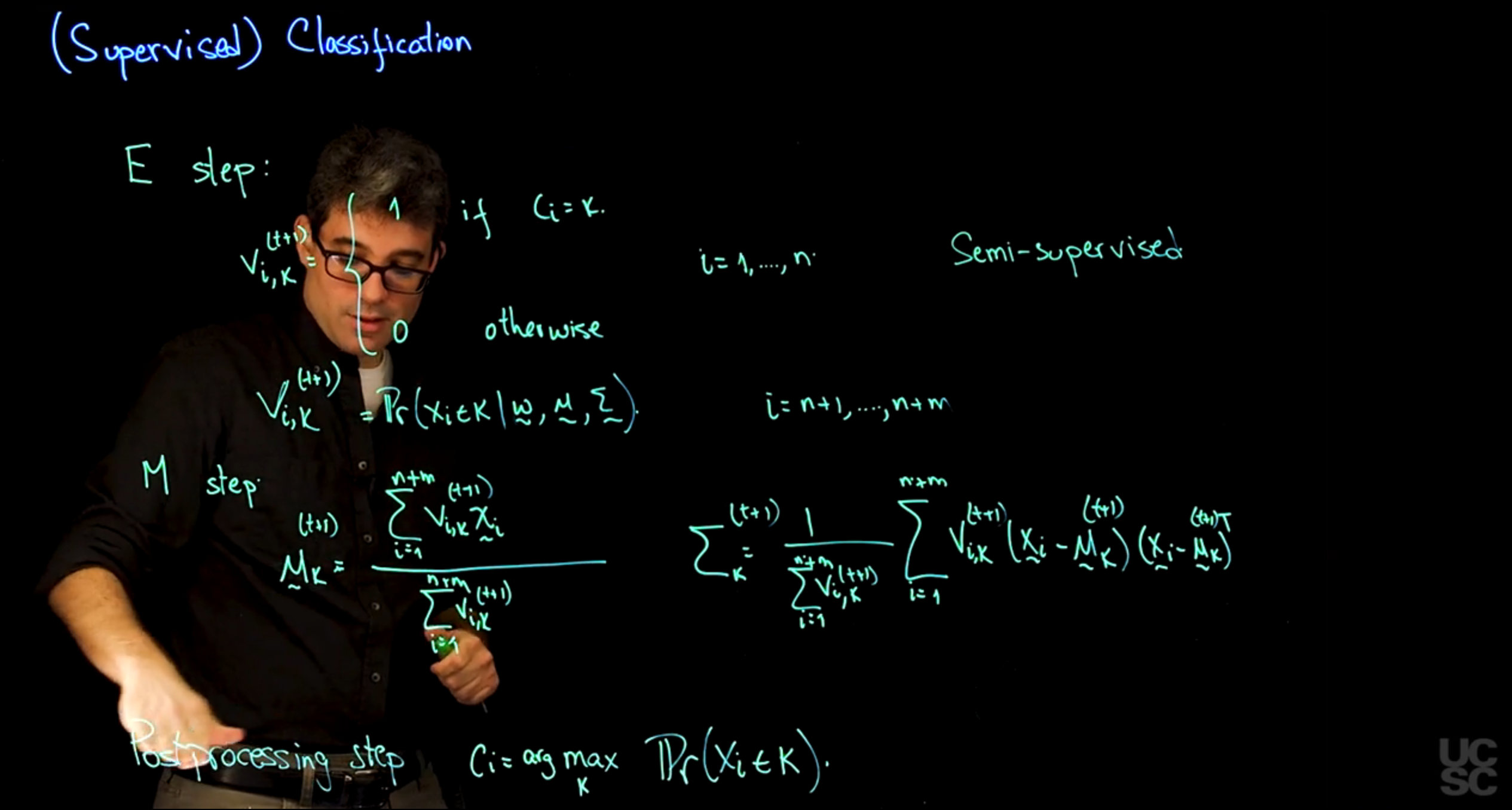

And let’s think about how the procedure would look like if we were to do Naïve Bayes classification using this mixture. If I follow the unsupervised example that I have discussed before, the probability that I put observation i in class, 1, say, I only have two classes.

So as you see again, consider one of them and the other one is just 1- the numbers that I get here. It’s going to be equal.

And I’m going to expand this in all its glory. It’s going to be a little bit long. So it’s going to be omega 1, 1 over the square root 2pi to the p determinant of sigma to the- 1 half, x of- 1 half, x- mu k transpose sigma inverse x- mu k. And in the denominator, we’re going to have the same expression first. And then we’re going to have omega 2, that is just 1- omega 1 but 2pi to the p determinant of sigma to the- 1 half x- 1 half x- mu 2, sigma inverse x- mu 2. Okay, and we know that the probability that xi belongs to class 1 is exactly the same expression but replacing mu, 1 which is what should be up here, replacing mu1 with mu2.

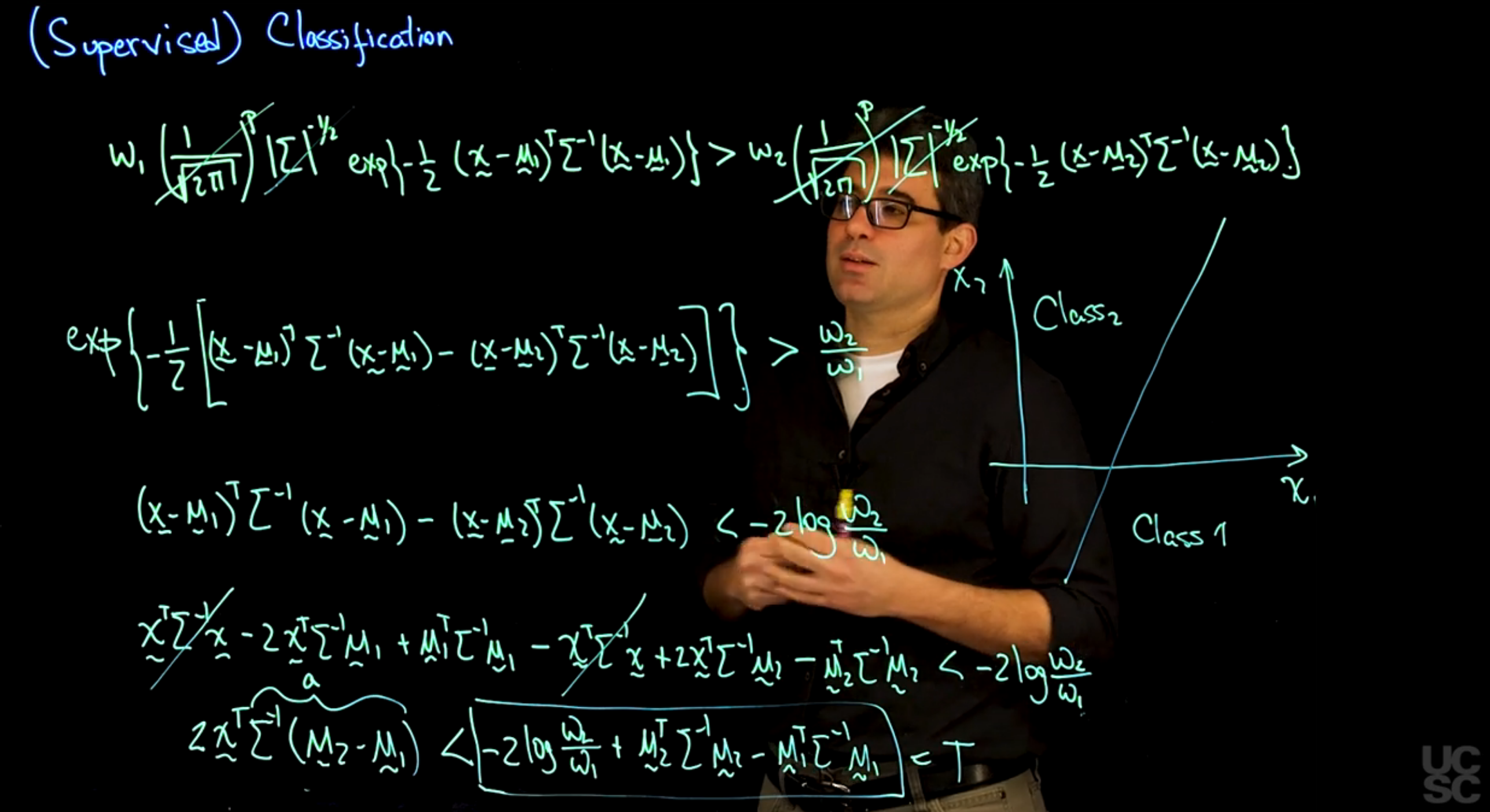

So, in the post processing step, we are going to assign C sub i = 1 if and only if the probability that xi belongs to class 1 is greater than the probability that xi belongs to class 2. And because the two expressions are the same in the denominator, the only thing that changes is the numerator, then this happens if and only if omega 1, 1 over the square root 2pi to the p determinant sigma to the- 1 half x- 1 half, X- mu1 transpose sigma inverse x- mu1, Is greater than omega 2, 1 over the square root 2pi to the p determinant of sigma to the- 1 half x of- 1 half x- mu2, sigma inverse x- mu2. So probability of class 1 greater than probability of class 2 only if this quantity is greater than the same thing but evaluated for the second component in the mixture. So let’s do a little bit of algebra and let’s try to simplify this expression a little bit and we will see that that simplification leads to a very nice expression that matches exactly what you get out of linear discriminant analysis. So now we want to simplify this expression that corresponds to the situation where we’re going to label an observation coming from class 1, and we want to make it much more compact. So a few things that we can observe. So one of them is we have 1 over square root 2pi to the p on both sides, so we can cancel that. The other thing that we observe is that we have the determinant of the variance-covariance matrix on both sides. And because we’re assuming that the two components have the same variance- covariance matrix, we can again just simplify both terms on either side. And the next thing that I’m going to do is I’m going to move all the omegas to one side and bring all the terms with the exponentials to the other side. If I do that, I’m going to end up on the left hand side with the exponent of- 1 half, X- mu1 transpose sigma inverse x- mu1. And then this term came to the other side in the denominator, but that just means that when it goes into the exponential, I need to change all to reverse signs. So it’s going to be- x- mu2 transpose sigma inverse x- mu2. So that’s the expression once you move this to the denominator and combine the two exponentials. And this needs to be greater than omega 2 divided by omega 1. Now, some further simplifications. I can take the logarithm on both sides and I can multiply by -2 on both sides, and I end up with an expression that looks like x- mu 1 transpose sigma inverse x- mu1- x- mu 2 transpose sigma inverse x- mu 2 has to be less than, because I’m going to end up multiplying by a -2. So less than -2 log of omega 2 divided by omega 1. So now we have this difference of two quadratic forms needs to be less than a certain constant that depends on what are my prior weights for each one of the two components. Now, to finish simplifying this, we need to expand these two squares, which is pretty straightforward. So first we’re going to have x sigma inverse x transpose sigma inverse x. This is just a square. So it’s going to be 2 times x transpose sigma inverse mu1. And finally, \mu_1 transpose sigma inverse \mu_1. And then we need to subtract a similar expression but using mu2 for it turns. So it’s going to be x transpose sigma inverse x. It’s going to be +, in this case, 2x transpose sigma inverse mu2. And finally, again,- mu2 transpose sigma inverse mu2, and all of these needs to be less than -2 log of omega 2, Divided by omega 1. So you can see that the expressions are relatively straightforward.

And one of the things that is very nice, and it’s a consequence of having the same variance-covariance matrix for each one of the components, is that now this quadratic term of the data is going to cancel out. And so, we can just basically learn together a couple of terms. So we can write, 2 times, X transpose sigma inverse multiplied by mu2- mu1. So I’m taking this term and combining it with this term. So, the term here and the term here.

And then I’m going to say that this has to be less than -2 times log of omega 2 divided by omega 1, and I’m going to move this two terms to the right. So,+ mu2 transpose sigma inverse mu2- mu1 transpose sigma inverse mu1. So this is actually quite a bit of simplification and it’s a very interesting one. Because you can think about this, Thing on the right hand side, just call this T for threshold. So this is your sum threshold and that threshold is basically computed based on the training data. So if I know the classes of some observations, I can get what the means for each one of the classes are, I can estimate the common sigma, and I can estimate the relative frequencies. And with that, I can obtain a stress score from the training set. And I can think about this matrix product as sum vector a. The form of this simplified expression is very interesting. You can see that the right-hand side, all this expression in the box, it’s just a threshold that can be easily computed from the training set. We can estimate the weight and we can estimate the mean and the covariance of the two components. And then, this product of the variance-covariance or the inverse of the variance-covariance matrix times the difference of the means corresponds to a vector a that can also be computed from the training set. So essentially, the decision of whether we classify an observation in class 1 or class 2 is going to depend on whether a linear combination, and that’s what x transpose times a is, is just a linear combination of the values of x. So whether this linear combination of the values of x is greater than a given threshold or not. In other words, what we’re doing, In a setting where we only have two variables, for example, x1 and x2, the linear combination of the entries is just a line on the plane. So this product just corresponds to a line. And by deciding whether we are above the line or below the line, we’re just saying that one of the regions corresponds to class, 2, and the other region corresponds to class 1. So this is the reason why the procedure is called linear discriminant analysis because it uses a straight line to decide whether observations should be classified in class 1 and class 2. Now, there are some more interesting things that you can do.

For example, you don’t have to assume that the sigmas are the same, you could assume that the \sigma_i are different. If you were to do that, then you’d be in a situation that is analogous to this one with the main difference being that now these terms here wouldn’t necessarily simplify.

But then, you can rearrange terms in such a way that now, you’re going to have a quadratic form of x being less than a certain threshold. And in that case, you’re separating hyperplane.

Instead of being a hyperplane or line, it’s going to be a quadratic form. And that is the reason why when you’re doing Naïve Bayes and you’re working with kernels that are Gaussian and have different variance-covariance matrices, you call the procedure quadratic discriminant analysis. Because it uses a quadratic form, a parabola or something like that to separate the two classes that you’re working with.

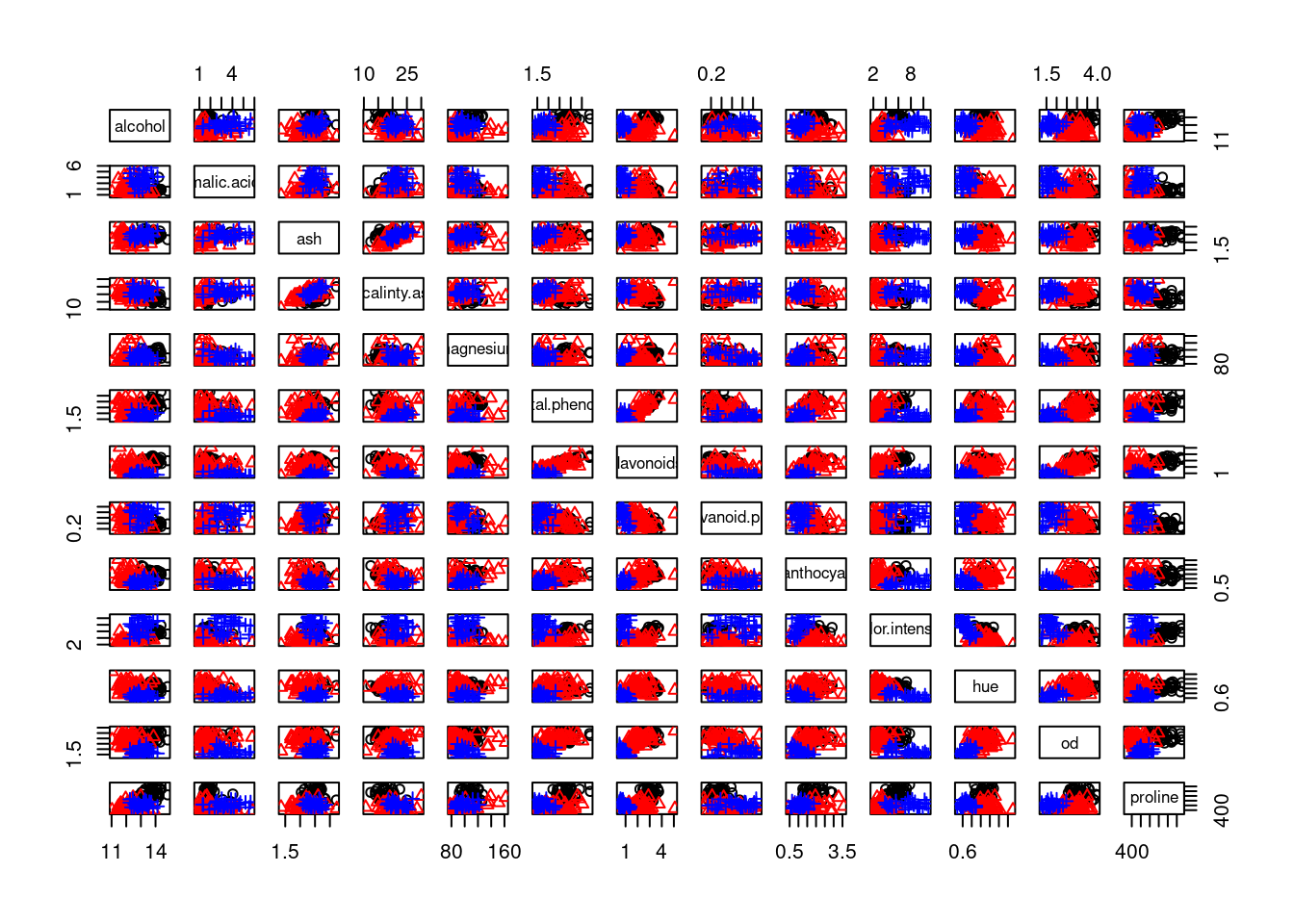

The nice thing about thinking about this classification procedures in the context of mixture models is again, thinking about ways in which you can generalize and address the shortcomings of the procedure. It’s clear that the main issue with classification procedures based on Gaussians is that data in the real world sometimes doesn’t look like multivariate Gaussian distributions.

One possible extension is to instead of considering the density, this ps here to be a single Gaussian, you can kind of use mixtures a second time and borrow some ideas from when we did density estimation. And say well, I’m going to have a mixture and each component of that mixture is in turn a second mixture that may have a few components. And that may allow for the shape of the clusters to be much more general, and that’s what we call mixture discriminant analysis.

As before, if you instead of doing the Algorithm and the simple maximum likelihood estimation that I described before, you instead use Bayesian estimators for your process, then you will have Bayesian equivalent of linear discriminant analysis and quadratic discriminant analysis. So it is very useful to think about your statistical methods in the context of mixture models for the purpose of both generalizing and understanding the shortcomings of what you’re doing.