Recently, I’ve been revisiting an old idea about creating a topological model of alignment. The machine translation task has been solved largely by using deep learning models. My idea was to leverage the unique structure of Wikipedia to learn to translate using non-parallel texts. The links in many case provide hints that could be used to tease out more and more word pairs and phrases that are translations.

Today I want to revisit this idea. I’m sure that even if it is only an idea, now I know more, like how to create embeddings for each language. How to make word sense embeddings, and how to create cross-language embeddings. This approach may be more feasible. I also learned how to represent a word as a word context pair. This is an idea that might have been useful in the original version. We also have wiki data with even more cross-language information unavailable.

On Tuesday, New York District Attorney Alvin Bragg announced that Luigi Mangione, 26, had been charged with first-degree murder in relation to the killing of UnitedHealthcare CEO Brian Thompson in Manhattan, New York, United States on December 4.

19 grudnia 2024 roku prokurator okręgowy Nowego Jorku Alvin Bragg ogłosił, że Luigi Mangione, 26 lat, został oskarżony o first-degree murder (morderstwo pierwszego stopnia) w związku z zabójstwem Briana Thompsona (dyrektora generalnego UnitedHealthcare) na Manhattanie 4 grudnia.

The Opening sentence from two stories in Wikinews with named entities highlighted. Although not makerd explicitly these matching landmarks induce a topology via neighborhoods on the remaining words that suggests which words and phrases might be in correspondence.

Also underlined are two items that are linked which have cross language links to 20+ languages.

While the in Wikipedia are what makes it a wiki they are just a step in the right direction. One can easily envision using linked data to highlight parallel-structure across a corpus. For news articles appearing in temporal-proximity this might be easier. But it should be possible to do so for any corpus of similar texts. With enough such links one can uncover a vast hierarchy of related words, terms, phrases, idioms, relations and events. And once a high percentage of these have been learned the rest of the text may be translated using this translation model. If we want to do even better we could list the most likely translations for the remaining words and phrases and subject them to further analysis. A RL agent might be trained to look for new items to add to the corpus and keep improving the translation model as a curriculum learning task.

This was based on work on Wikipedia, where hints like cross-language links, Wikidata, and templates provide valuable resources for learning translations, even when text varies or translations are incomplete. Over time, I became aware of more resources that could be used, such as movie subtitles, book translations, and parallel corpora. However, news articles and blogs are often not parallel; they can contain similar information.

I thought about this when I first took a class in topology in my second year at university. What we learned was that topologies have an interesting property. The product of a topology is also a topology, and also that topological properties are preserved by a homeomorphism.

I did not possess the modern view that the translation problem is one of alignment and segmentation. I was considering translation from the point of view of decryption, where one considers the incidence of coincidence that two tokens co-occur together and so on. I thought that what might scale better1 for translation is to find semantic compatible neighborhoods around semantic equivalent landmarks in texts that cover the same material2 and then use these as candidates for learning to translate. The text might be divergent, but if they covered the same content, many local neighborhoods must be very similar. If we see them several times. The landmarks might be to see how well words at different distances in that neighborhood to equivalent landmarks; these might allow us to learn to translate into parts that are small enough around proper nouns we should have many equivalent segments. And many more that are not. But we might be able to see if we can swap out various inverse images of the same segment. (Or perhaps check them for similarity) The inverse images are in the same language, so we only need to test for similarity in the same language, which is apparently an easier task.

1 i.e. this seems a self-supervised approach

2 e.g. new articles on recent breaking news

3 using cross-language links if they have an article or using a phonemic similarity

So, the crux is rather than looking at two parallel texts and trying to segment them into aligned units. I wanted to find local neighborhoods in the text that might be aligned and test the hypothesis that they are translations of each other. For example, in Wikipedia, there are many sections with common titles. These sections often contain similar information and many named entities that one can match 3. This would then allow one to tackle sections with less common titles. We might not learn to translate them, but we could perhaps learn how likely they are to be equivalent. (Using a simple vector base similarity with a threshold)

I thought that words in an article have neighborhoods that capture meanings. However, there are often alternate versions of the same article in many languages. Translation is generally hard - we must align the words in the source and target. Also, sometimes words are missing or there are extra words.

A second issue was that the texts in different language editions are not translations but independent works. (Although sometimes an editor will translate a whole or parts of an article rather than write it from scratch.) So, using non-parallel text to learn translation seems like a problem. I was young and optimistic. Surely, over time, more and more of Wikipedia’s articles converge across languages, so there would be many sections with equivalent content. If we could consider them locally, we might tease out a way to learn to translate. Say we could find landmark words like names of places or people we already knew how to translate. If we tracked these in the English and French versions, we get a neighborhood of words more likely to be equivalent if not a translation of each other. The more landmarks we could find, the smaller the neighborhoods would be and the more likely we could find translations or decide that certain neighborhoods are incompatible4. All one would need is to map the text into neighborhoods and then find neighborhoods highly likely to be translations of each other. We might consider the words in their neighborhoods as candidates for translation. This would be easier the more neighborhoods we could translate. 5

4 we would exclude incompatible neighborhoods from further analysis, but such incompatible neighborhoods are of great interest as well, if not for translation, for understanding how each culture thinks about each topic differently

5 Another direction is to look at some global metric that could be used to assign rewards for finding translations and matches and use these for RL-type planning.

This seems hopeless at first.

However, the many links in the wiki might hint at how to align certain words.

I was convinced that learning to translate might be done by considering many problems one at a time. One would start by using cross-language information that links the articles across languages. Collect statistics on neighborhoods for these landmarks. Check their inverse image. (Inverse images of different sizes can detect/fix certain alignment errors.)

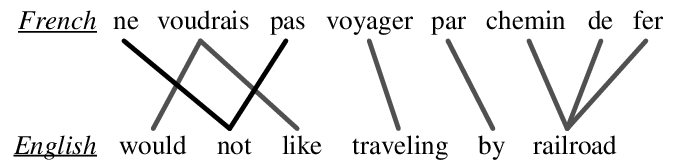

in figure 1

I had heard about LDA (citationneeded?), which allows the creation of cross-linguistic representations by simply appending similar text in different languages.

This was an example of a semantic algorithm.

I considered that the links in a wiki i.e., between articles, define

If we look at the Twitter feeds, we can see that people often tweet the same news in different languages. This is a good source of parallel data. We can run this through a translation model and then use the output to learn alignment and segmentation. It would be even more useful if we captured sequences of tweets about the same news item. In this case, we might look at aligning or predicting emojis.

Ideally, one would like to learn unsupervised alignment and segmentation by simply deleting parts of one document and then trying to predict the missing parts using the other document. The model could learn to do this better by segmenting and aligning the documents.

Another interesting idea is to learn ancillary representation for alignment and segmentation for each language. This is an idea I got from my work on language evolution. Instead of learning the whole grammar, we might try to model the most common short constructs in each language. With a suitable loss function, we might find a pragmatic representation useful for alignment and segmentation for a language pair. Of course, such representations would be useful for other tasks as well.

This might be much easier if we provide chunks of decent size for training. We might first use very similar documents (from a parallel corpus) and later move to new articles or papers that are more loosely related.

Segmentation and Alignment are two related tasks that are often done together and, in this abstract view, more widely applicable than just in translation, e.g., DNA and time series. However, this post will focus primarily on translation.

I guess the algorithm should need to:

find a segment in the source, and decide if

there is a similar segment in the other text.

multiple segments match. (due to morphology, metaphor, or lack of a specific word in the target language)

the segment is missing in the other text.

a conflicting segment is present in the other text.

if the segment is a non-text segment (markup, templates, images, tables, etc.)

if the segment is a named entity or a place name that requires transliteration or lookup in a ‘knowledge base’

The original idea was to use these hints to learn to align the documents at a rough level by providing a rough topology for each document. The open sets would be mappable to each other. They could then be concatenated to learn Latent Semantic Alignment or Latent Dirichlet Allocation.

Topologies can then be refined by using cross-language word models on the segments deemed to be similar.

One tool that might be available today is to use cross-language word embeddings.

These should allow us to align the documents at a much finer level.

Word embeddings are often unavailable for all words, such as names, places, etc. This is where the hints come in. Learning transliteration models can be a second tool that can help.

A second notion is to develop phrase embeddings. These could be used to better handle one too many mappings arising from the morphological differences between languages.

A second idea is that once we have alignments, we can learn pooling priors for different constructs and achieve better translation defaults.

The Phrase embeddings might have combined a simple structural representation and a semantic representation. The structural representation would be used to align the phrases, and the semantic representation would be used to align the words within the phrases. The semantic representation would be grounded in the same high-dimensional semantic space as the word embeddings.

BITEXT AND ALIGNMENT

A bitext B = (Bsrc , Btrg ) is a pair of texts B_{src} and B_{trg} that correspond to each other.

B_{src} = (s_1 , ..., s_N ) and B_{trg} = (t_1 , .., t_M )

Empty elements can be added to the source and target sentences to allow for empty alignments corresponding to deletions/insertions.

(p || r) = (s_{x1} , .., s_{xI} )||(t_{y1} , .., t_{yJ} ) with 1 ≤ x_i ≤ N for all i = 1..I and 1 ≤ y_j ≤ M for all j = 1..J

An alignment A is then the set of bisegments for the entire bitext.

This should be a bijection, but it is not always the case.

bitext links L = l_1 , .., l_K which describe such mappings between elements s_x and s_y : l_k = (x, y) with 1 ≤ x ≤ N and 1 ≤ y ≤ M for all k = 1..K. The set of links can also be referred to as a bitext map that aligns bitext positions with each other. Such a bitext map can then be used to induce an alignment A in the original sense

Extracting bisegments from this bitext map can be seen as the task of merging text elements in such a way that the resulting segments can be mapped one-to-one without violating any connection.

- Text linking

-

Find all connections between text elements from the source and the target text according to some constraints and conditions that describe the correspondence relation of the two texts. The link structure is called a bitext map and may be used to extract bisegments.

- Bisegmentation

-

Find source and target text segmentations such that there is a one-to-one mapping between corresponding segments

Segmentation

is the task of dividing a text into segments. Segmentation can be done at different levels of granularity, such as word, phrase, sentence, paragraph, or document level.

For alignment, to successfully align two texts, the segments should be of the same granularity.

It is often frustrating to align Hebrew texts with their rich morphology to English because one Hebrew word frequently matches several English words. Annotators will then segment the Hebrew words with one letter in some segments, which may correspond to a English word e.g. a particle.

Different granularity of segmentation are:

morpheme (sub-word semantic segmentation)

character segmentation

word segmentation

token segmentation

lemma segmentation (token clusters)

n-gram segmentation

phrase segmentation

sentence segmentation

paragraph segmentation

syntactic constituent segmentation

Basic entropy/statistical tools should be helpful here to identify and learn good segmentation for the different languages and possibly how to align them.

I.e., where morpheme boundaries lie and where clause/phrase boundaries lie.

This is where another idea comes in. Some advanced TS models can combine local behavior and long-term behavior into a single model.

Further work

look into:

Citation

@online{bochman2024,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

date = {2024-10-01},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/posts/2024/2024-10-01-alignment/2024-10-01-alignment.html},

langid = {en}

}