Lecture 14a Learning layers of features by stacking RBMs

Training a deep network by stacking RBMs

- First train a layer of features that receive input directly from the pixels.

- Then treat the activations of the trained features as if they were pixels and learn features of features in a second hidden layer.

- Then do it again.

- It can be proved that each time we add another layer of features we improve a variational lower bound on the log probability of generating the training data.

- The proof is complicated and only applies to unreal cases.

- It is based on a neat equivalence between an RBM and an infinitely deep belief net (see lecture 14b).

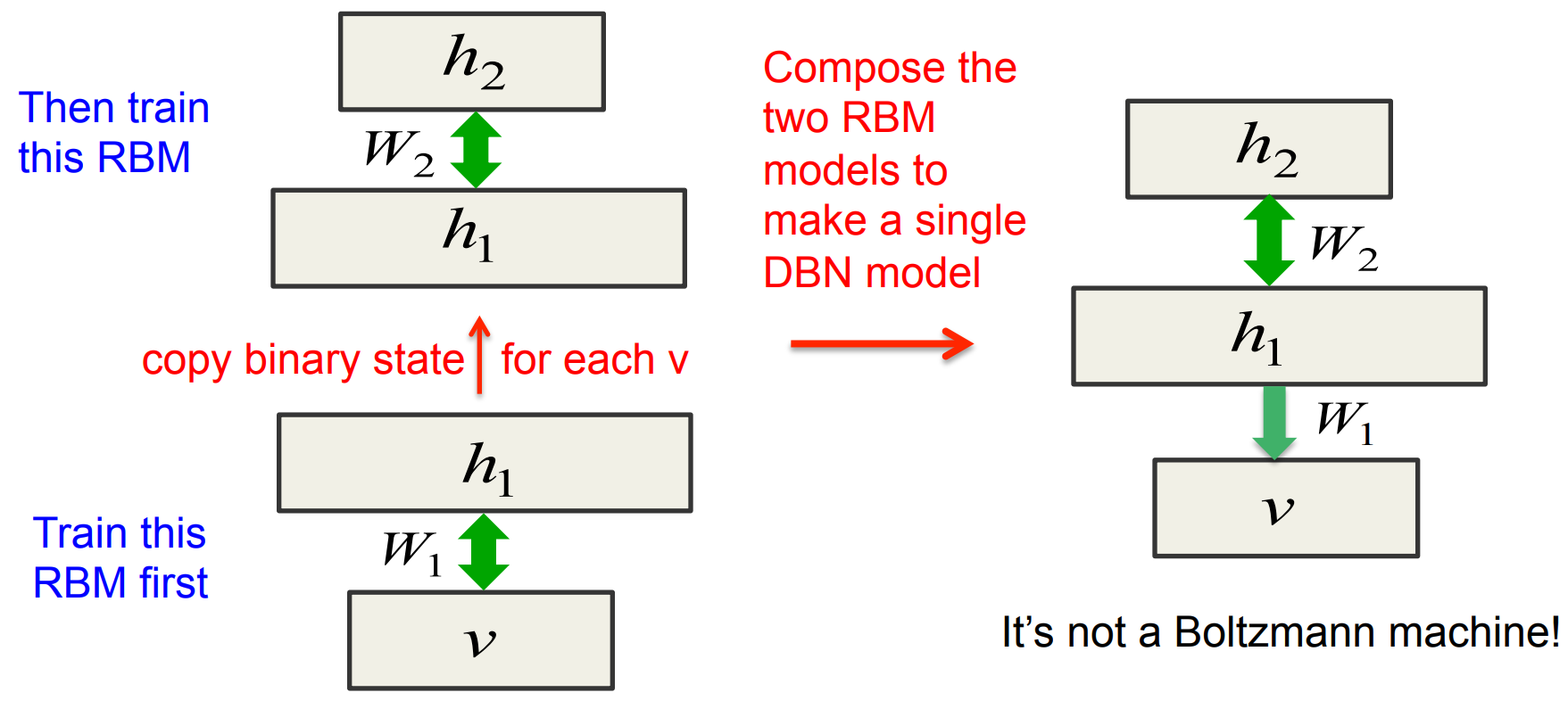

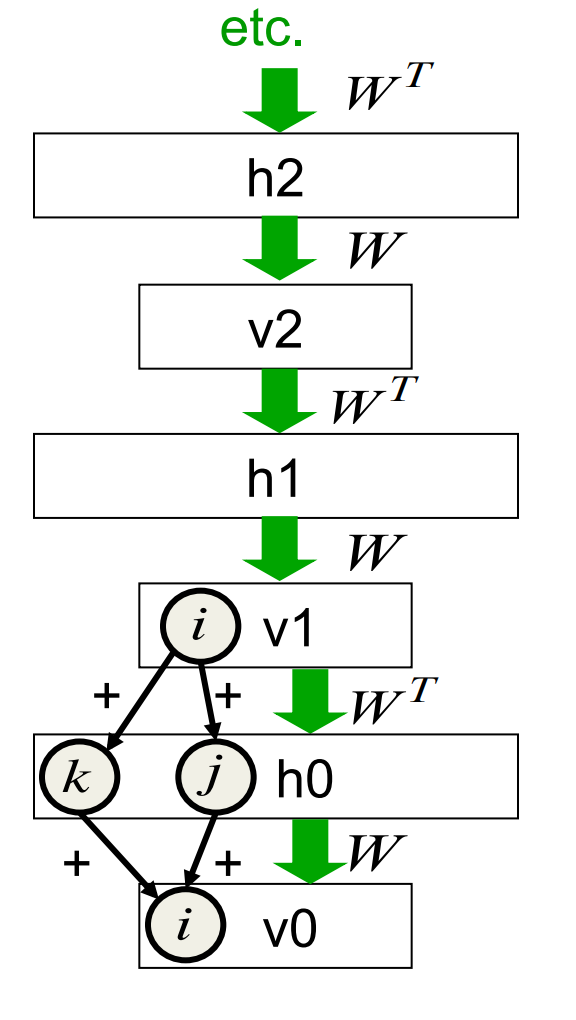

Combining two RBMs to make a DBN

To generate data:

- Get an equilibrium sample from the toplevel RBM by performing alternating Gibbs sampling for a long time.

- Perform a top-down pass to get states for all the other layers.

The lower level bottom-up connections are not part of the generative model. They are just used for inference.

An aside: Averaging factorial distributions

- If you average some factorial distributions, you do NOT get a factorial distribution.

- In an RBM, the posterior over 4 hidden units is factorial for each visible vector.

- Posterior for v1: 0.9, 0.9, 0.1, 0.1

- Posterior for v2: 0.1, 0.1, 0.9, 0.9

- Aggregated = 0.5, 0.5, 0.5, 0.5

- Consider the binary vector 1,1,0,0.

- in the posterior for v1, p(1,1,0,0) = 0.9^4 = 0.43

- in the posterior for v2, p(1,1,0,0) = 0.1^4 = .0001 – in the aggregated posterior, p(1,1,0,0) = 0.215.

- If the aggregated posterior was factorial it would have p = 0.5^4

Why does greedy learning work?

The weights, W, in the bottom level RBM define many different distributions: p(v|h); p(h|v); p(v,h); p(h); p(v).

We can express the RBM model as

p(v)= \sum_h p(h) p(v \mid h)

If we leave p(v|h) alone and improve p(h), we will improve p(v).

To improve p(h), we need it to be a better model than p(h;W) of the aggregated posterior distribution over hidden vectors produced by applying W transpose to the data.

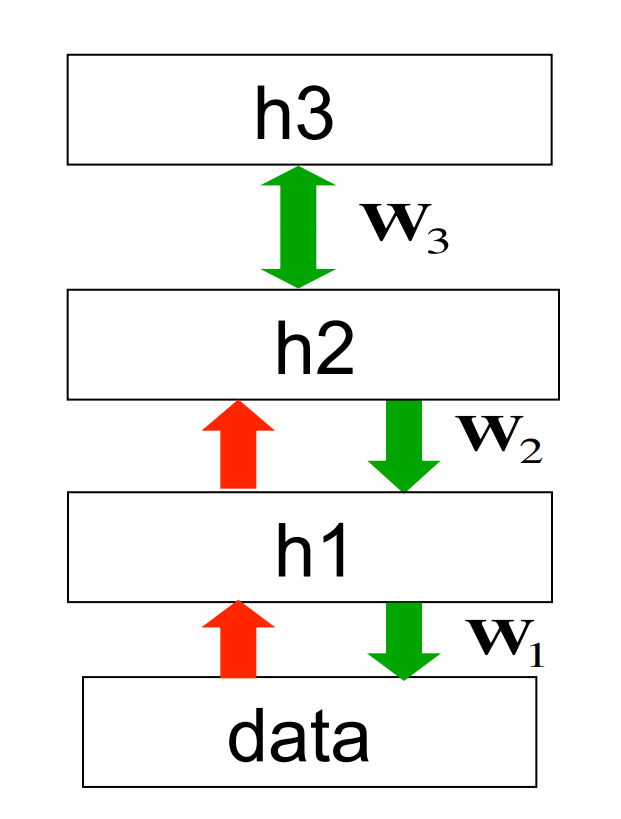

Fine-tuning with a contrastive version of the wake-sleep algorithm

After learning many layers of features, we can fine-tune the features to improve generation.

- Do a stochastic bottom-up pass

- Then adjust the top-down weights of lower layers to be good at reconstructing the feature activities in the layer below.

- Do a few iterations of sampling in the top level RBM

- Then adjust the weights in the top-level RBM using CD.

- Do a stochastic top-down pass

- Then Adjust the bottom-up weights to be good at reconstructing the feature activities in the layer above.

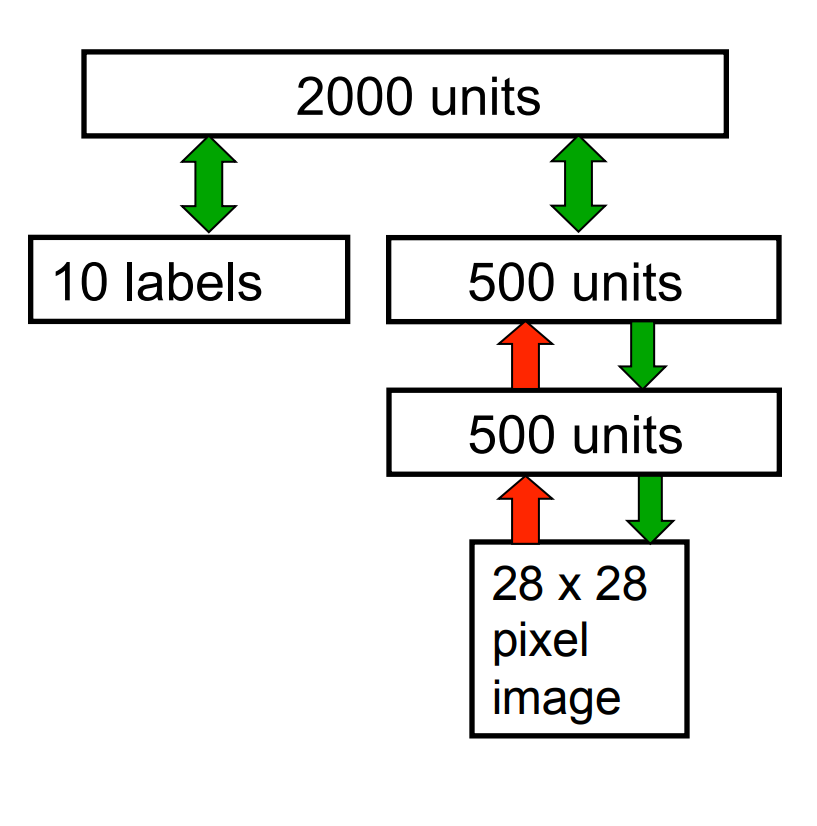

The DBN used for modeling the joint distribution of MNIST digits and their labels

- The first two hidden layers are learned without using labels.

- The top layer is learned as an RBM for modeling the labels concatenated with the features in the second hidden layer.

- The weights are then fine-tuned to be a better generative model using contrastive wake-sleep.

Lecture 14b Discriminative fine-tuning for DBNs

Fine-tuning for discrimination

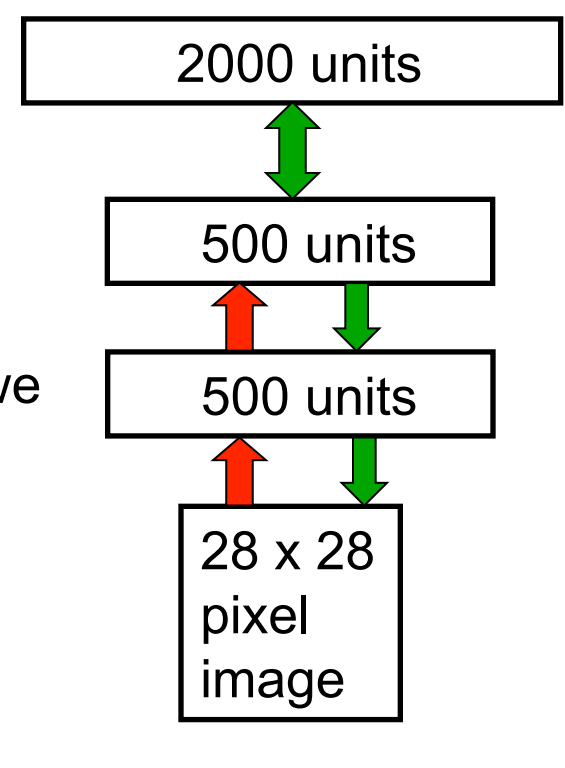

- First learn one layer at a time by stacking RBMs.

- Treat this as “pre-training” that finds a good initial set of weights which can then be fine-tuned by a local search procedure.

- Contrastive wake-sleep is a way of fine-tuning the model to be better at generation.

- Backpropagation can be used to fine-tune the model to be better at discrimination.

- This overcomes many of the limitations of standard backpropagation.

- It makes it easier to learn deep nets.

- It makes the nets generalize better.

Why backpropagation works better with greedy pre-training: The optimization view

- Greedily learning one layer at a time scales well to really big networks, especially if we have locality in each layer.

- We do not start backpropagation until we already have sensible feature detectors that should already be very helpful for the discrimination task.

- So the initial gradients are sensible and backpropagation only needs to perform a local search from a sensible starting point

Why backpropagation works better with greedy pre-training: The overfitting view

- Most of the information in the final weights comes from modeling the distribution of input vectors.

- The input vectors generally contain a lot more information than the labels.

- The precious information in the labels is only used for the fine tuning.

- The fine-tuning only modifies the features slightly to get the category boundaries right. It does not need to discover new features.

- This type of back-propagation works well even if most of the training data is unlabeled.

- The unlabeled data is still very useful for discovering good features.

- An objection: Surely, many of the features will be useless for any particular discriminative task (consider shape & pose).

- But the ones that are useful will be much more useful than the raw inputs.

First, model the distribution of digit images

The top two layers form a restricted Boltzmann machine whose energy landscape should model the low dimensional manifolds of the digits

The network learns a density model for unlabeled digit images. When we generate from the model we get things that look like real digits of all classes.

But do the hidden features really help with digit discrimination? Add a 10-way softmax at the top and do backpropagation.

Results on the permutation-invariant MNIST task

| paper | Error rate |

|---|---|

| Backprop net with one or two hidden layers (Platt; Hinton) | 1.6% |

| Backprop with L2 constraints on incoming weights | 1/4% |

| Support Vector Machines (Decoste & Schoelkopf, 2002) | 1.4% |

| Generative model of joint density of images and labels (+ generative fine-tuning) | 1.25% |

| Generative model of unlabelled digits followed by gentle backpropagation (Hinton & Salakhutdinov, 2006) | 1.15%->1.0% |

Unsupervised “pre-training” also helps for models that have more data and better priors

- In Ranzato et al. (2006) the authors used an additional 600,000 distorted digits.

- They also used convolutional multilayer neural networks.

Back-propagation alone: 0.49% Unsupervised layer-by-layer pre-training followed by back-prop: 0.39% (record at the time)

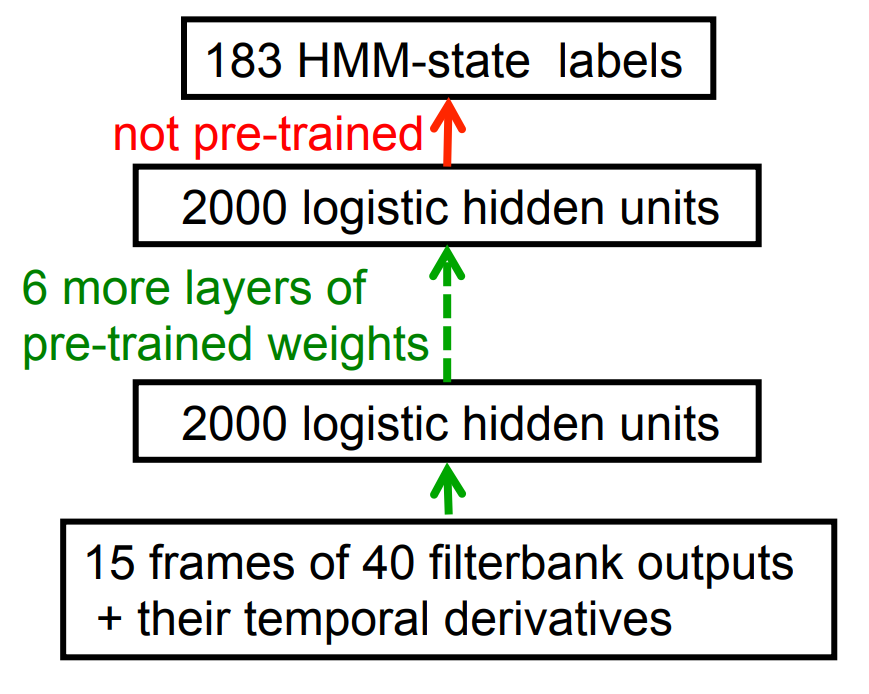

Phone recognition on the TIMIT benchmark (Mohamed, Dahl, & Hinton, 2009 & 2012)

- After standard post-processing using a bi-phone model, a deep net with 8 layers gets 20.7% error rate.

- The best previous speaker independent result on TIMIT was 24.4% and this required averaging several models.

- Li Deng (at MSR) realized that this result could change the way speech recognition was done. It has!

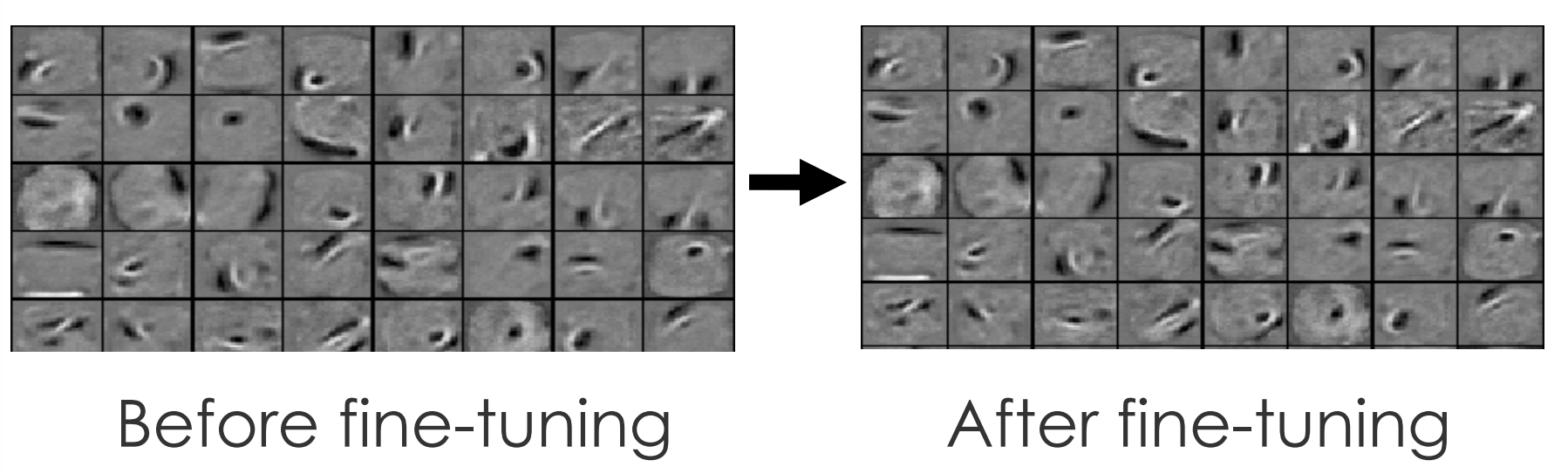

Lecture 14c What happens during discriminative fine-tuning?

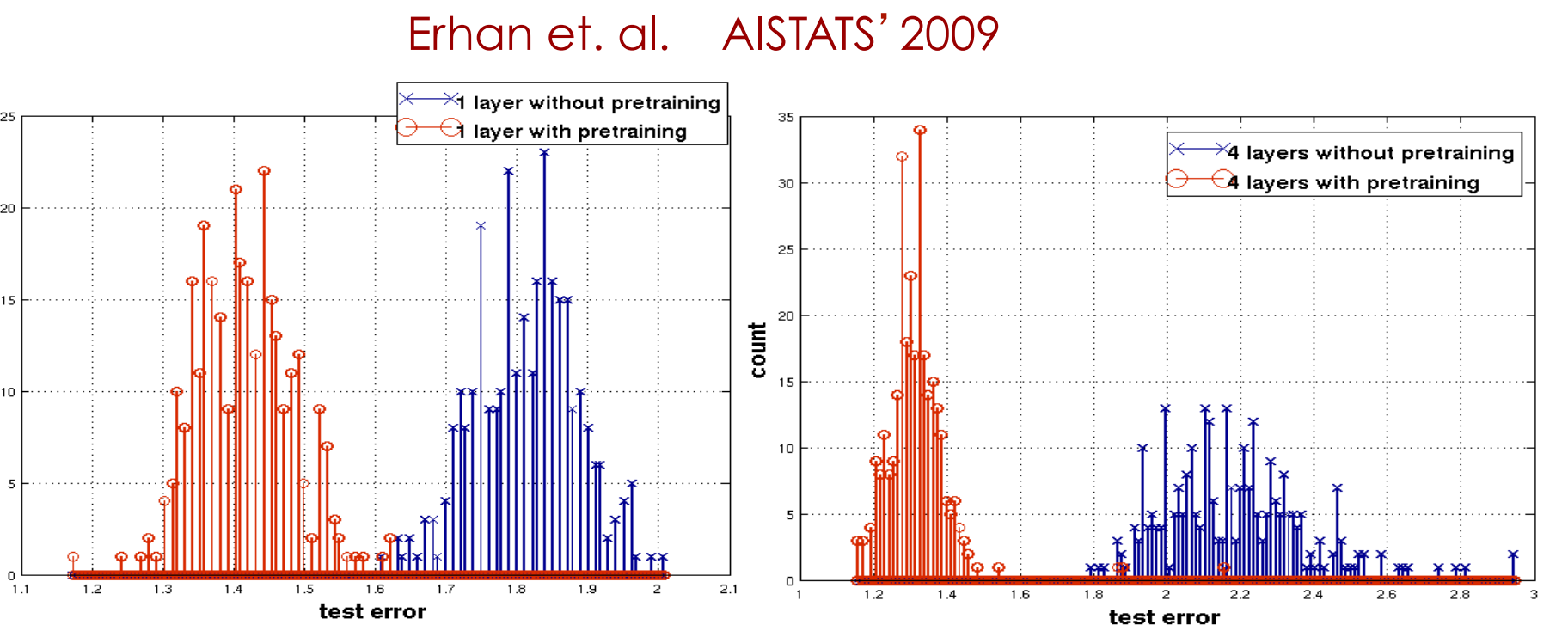

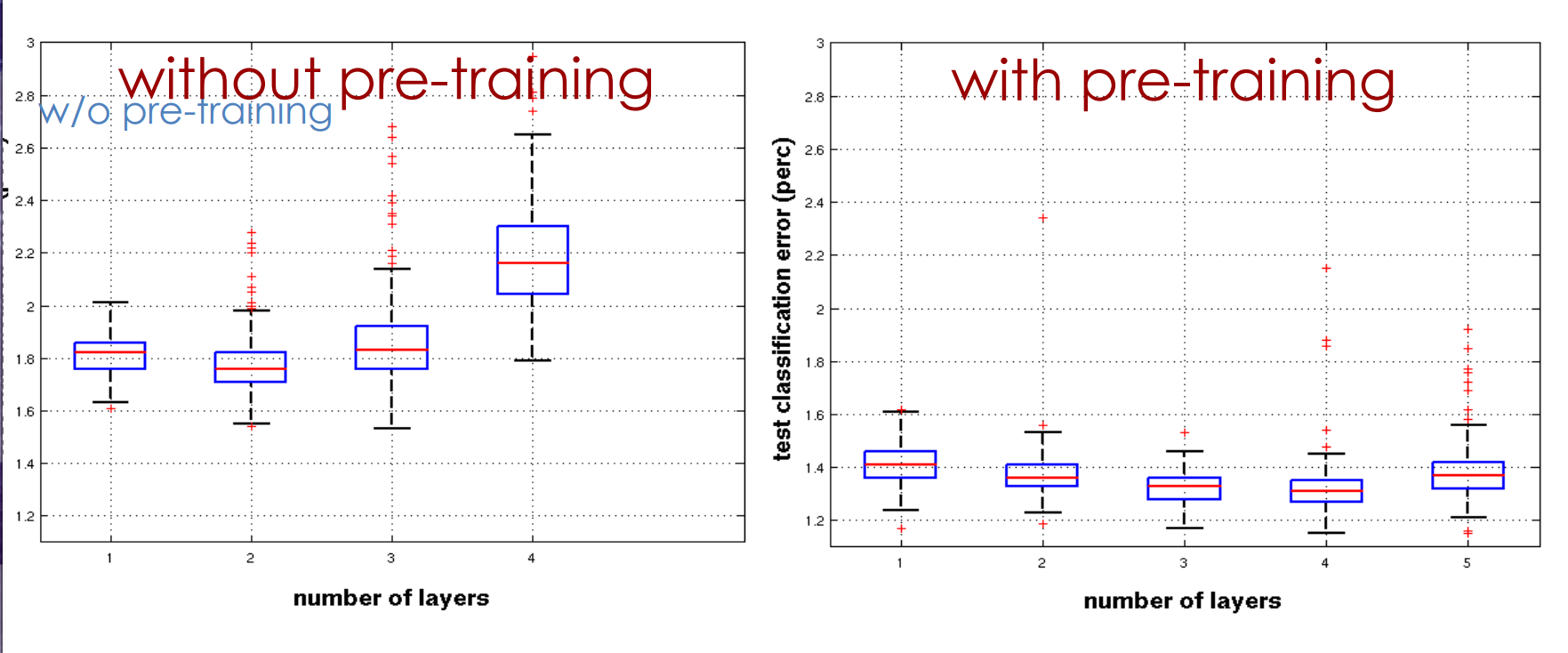

Learning Dynamics of Deep Nets the next 4 slides describe work by Yoshua Bengio’s group

Effect of Unsupervised Pre-training

Effect of Depth

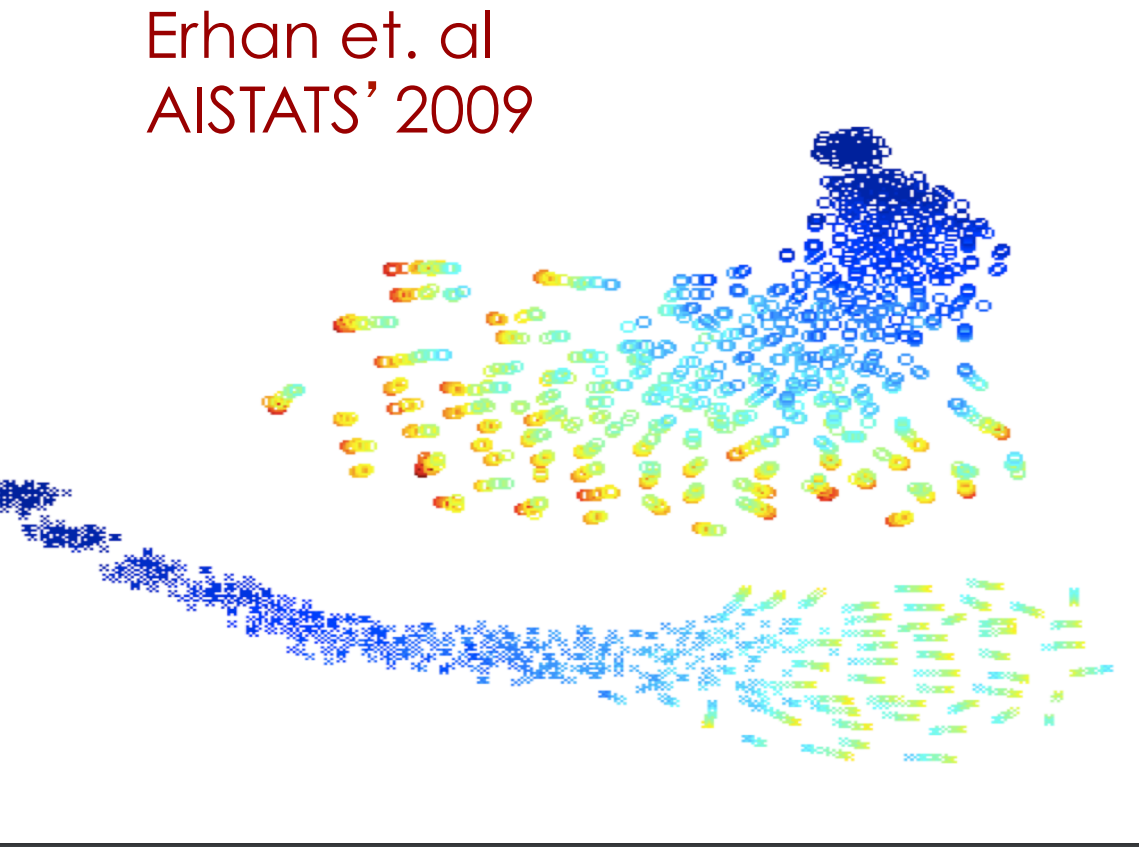

Trajectories of the learning in function space

Each point is a model in function space

- Color = epoch

- Top: trajectories without pre-training. Each trajectory converges to a different local min.

- Bottom: Trajectories with pre-training.

- No overlap!

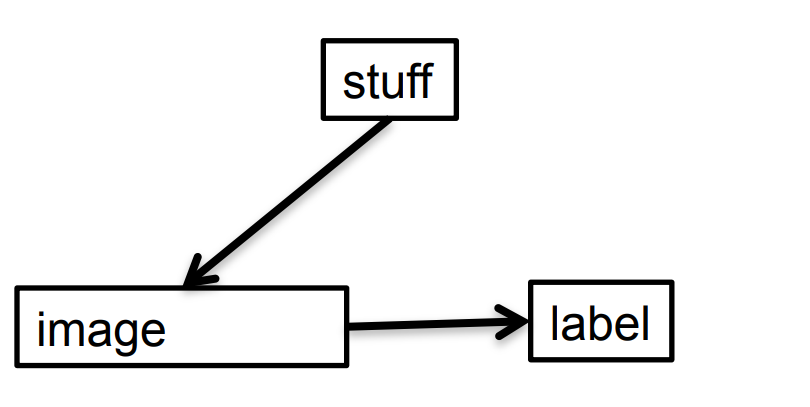

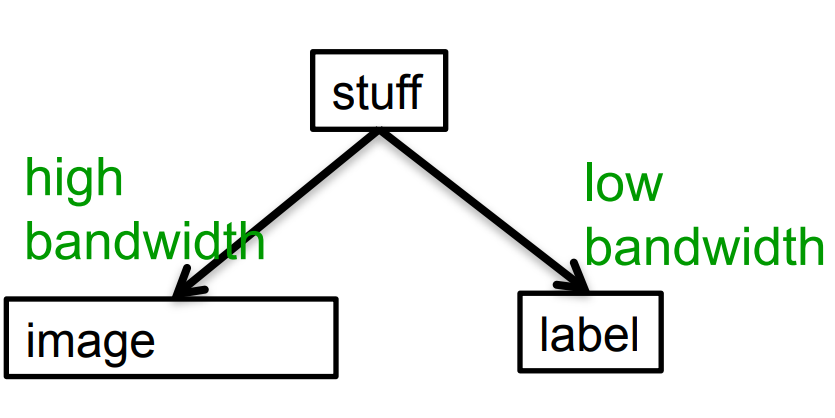

Why unsupervised pre-training makes sense

- If image-label pairs were generated this way, it would make sense to try to go straight from images to labels. For example, do the pixels have even parity?

If image-label pairs are generated this way, it makes sense to first learn to recover the stuff that caused the image by inverting the high bandwidth pathway.

Lecture 14dModeling real-valued data with an RB

Modeling real-valued data

- For images of digits, intermediate intensities can be represented as if they were probabilities by using “mean-field” logistic units.

- We treat intermediate values as the probability that the pixel is inked.

- This will not work for real images.

- In a real image, the intensity of a pixel is almost always, almost exactly the average of the neighboring pixels.

- Mean-field logistic units cannot represent precise intermediate values.

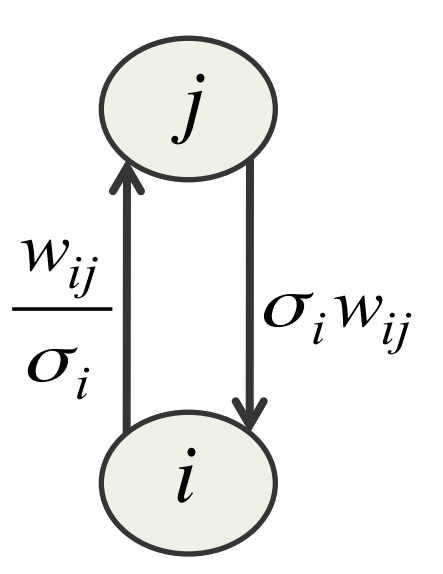

A standard type of real-valued visible unit

- Model pixels as Gaussian variables. Alternating Gibbs sampling is still easy, though learning needs to be much slower.

E(v,h) = \sum_{i\in vis} \frac{(v_i-b_i)^2}{2\sigma^2_i} - \sum_j b_jh_j- \sum_{i,j} \frac{v_i}{\sigma_i} h_i w_{ij} where:

- the first term is parabolic containment function

- the last term is energy-gradient produced by the total input to a visible unit

Gaussian-Binary RBM’s

Lots of people have failed to get these to work properly. Its extremely hard to learn tight variances for the visible units.

- It took a long time for us to figure out why it is so hard to learn the visible variances.

When sigma is small, we need many more hidden units than visible units.

This allows small weights to produce big top-down effects.

When sigma is much less than 1, the bottom-up effects are too big and the top-down effects are too small.

Stepped sigmoid units: A neat way to implement integer values

- Make many copies of a stochastic binary unit.

- All copies have the same weights and the same adaptive bias, b, but they have different fixed offsets to the bias:

b −0.5,\ b −1.5,\ b −2.5, b −3.5,\ \ldots ## Fast approximations

\langle y \rangle = \sum_{n=1}^{\infty} \sigma (x + 0.5− n) ≈ log(1+ e^x) ≈ max(0, x + noise)

- Contrastive divergence learning works well for the sum of stochastic logistic units with offset biases.

- The noise variance is \sigma(y)

- It also works for RELUs, which are faster to compute than the sum of many logistic units with different biases.

A nice property of rectified linear units

- If a RELU has a bias of zero, it exhibits scale equivariance:

- This is a very nice property to have for images.

- It is like the equivariance to translation exhibited by convolutional nets.

R(shift(x)) = shift(R(x)) # Lecture 14e : RBMs are Infinite Sigmoid Belief Nets

This is advanced material

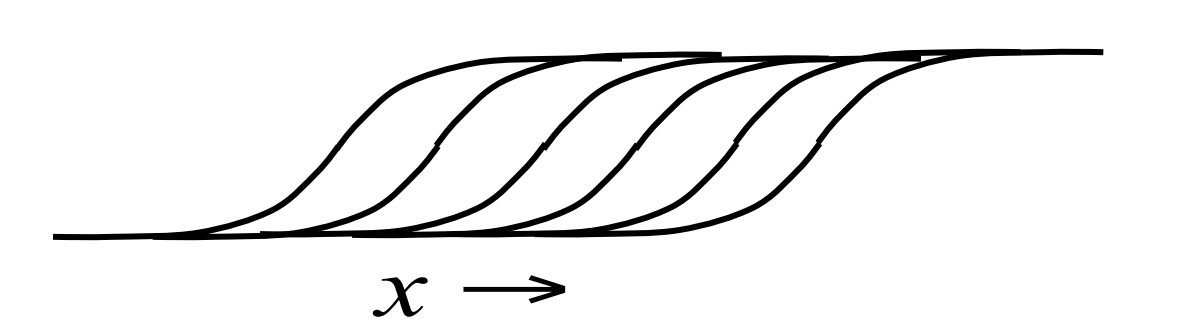

Another view of why layer-by-layer learning works — Hinton, Osindero, and Teh (2006)

- There is an unexpected equivalence between RBM’s and directed networks with many layers that all share the same weight matrix.

- This equivalence also gives insight into why contrastive divergence learning works.

- An RBM is actually just an infinitely deep sigmoid belief net with a lot of weight sharing.

- The Markov chain we run when we want to sample from the equilibrium distribution of an RBM can be viewed as a sigmoid belief net.

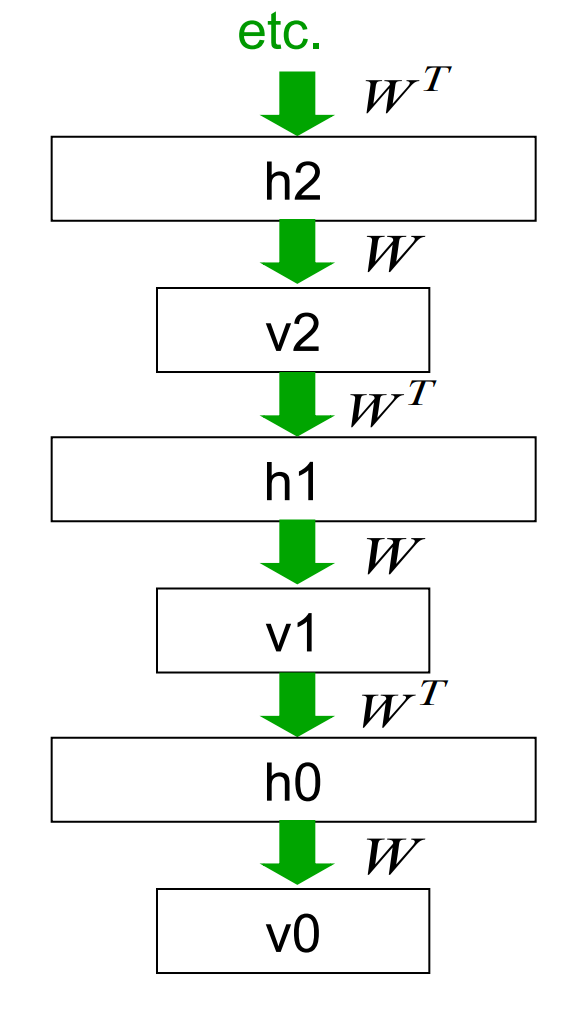

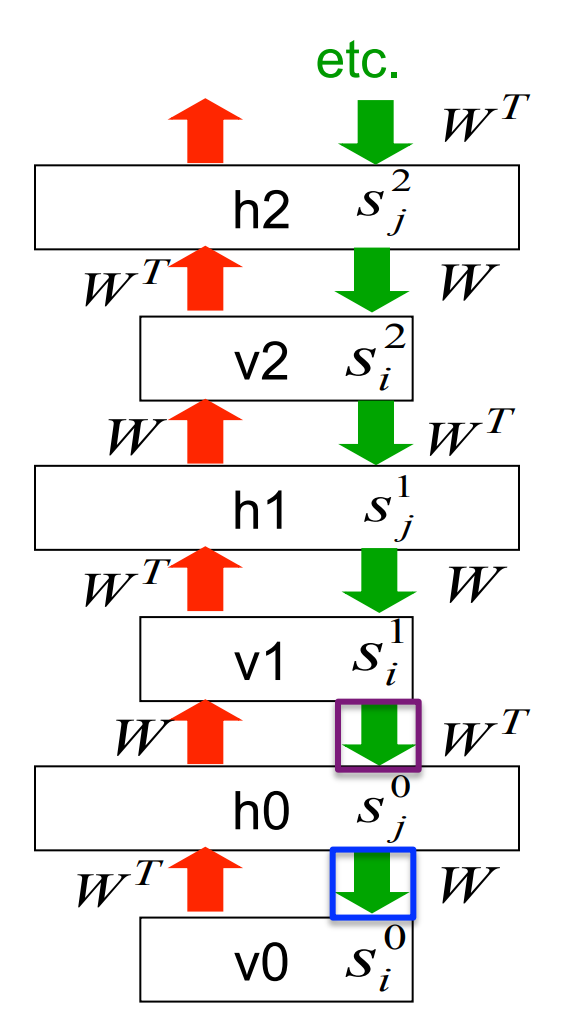

An infinite sigmoid belief net that is equivalent to an RBM

- The distribution generated by this infinite directed net with replicated weights is the equilibrium distribution for a compatible pair of conditional distributions: p(v \mid h) and p(h \mid v) that are both defined by W

- A top-down pass of the directed net is exactly equivalent to letting a Restricted Boltzmann Machine settle to equilibrium.

- So this infinite directed net defines the same distribution as an RBM

Inference in an infinite sigmoid belief net

- The variables in h_0 are conditionally independent given v_0.

- Inference is trivial. Just multiply v_0 by W^T

- The model above h0 implements a complementary prior.

- Multiplying v0 by gives the product of the likelihood term and the prior term.

- The complementary prior cancels the explaining away.

- Inference in the directed net is exactly equivalent to letting an RBM settle to equilibrium starting at the data.

- The learning rule for a sigmoid belief net is:

\Delta w_{ij} ∝ s_j(s_i − p_i)

where s_j^1 is an unbiased sample from p^i_0

- With replicated weights this rule becomes:

s_j^0 s_i^0 - s_j^\infty s_j^\infty

Learning a deep directed network

First learn with all the weights tied. This is exactly equivalent to learning an RBM.

- Think of the symmetric connections as a shorthand notation for an infinite directed net with tied weights.

We ought to use maximum likelihood learning, but we use CD1 as a shortcut.

Then freeze the first layer of weights in both directions and learn the remaining weights (still tied together).

- This is equivalent to learning another RBM, using the aggregated posterior distribution of h0 as the data.

What happens when the weights in higher layers become different from the weights in the first layer?

- The higher layers no longer implement a complementary prior.

- So performing inference using the frozen weights in the first layer is no longer correct.

- But its still pretty good.

- Using this incorrect inference procedure gives a variational lower bound on the log probability of the data.

- The higher layers learn a prior that is closer to the aggregated posterior distribution of the first hidden layer.

- This improves the network’s model of the data.

- In (Hinton, Osindero, and Teh 2006) the authors prove that this improvement is always bigger than the loss in the variational bound caused by using less accurate inference.

What is really happening in contrastive divergence learning?

- Contrastive divergence learning in this RBM is equivalent to ignoring the small derivatives contributed by the tied weights in higher layers.

Why is it OK to ignore the derivatives in higher layers?

- When the weights are small, the Markov chain mixes fast.

- So the higher layers will be close to the equilibrium distribution (i.e they will have “forgotten” the data vector).

- At equilibrium the derivatives must average to zero, because the current weights are a perfect model of the equilibrium distribution!

- As the weights grow we may need to run more iterations of CD.

- This allows CD to continue to be a good approximation to maximum likelihood.

- But for learning layers of features, it does not need to be a good approximation to maximum likelihood

References

Reuse

Citation

@online{bochman2017,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {Deep {Neural} {Networks} - {Notes} for {Lesson} 14},

date = {2017-11-21},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/notes/dnn/dnn-14/l_14.html},

langid = {en}

}