Lecture 8a A brief overview of “Hessian-Free” optimization

How much can we reduce the error by moving in a given direction?

- If we choose a direction to move in and we keep going in that direction, how much does the error decrease before it starts rising again? We assume the curvature is constant (i.e. it’s a quadratic error surface).

- Assume the magnitude of the gradient decreases as we move down the gradient (i.e. the error surface is convex upward).

- The maximum error reduction depends on the ratio of the gradient to the curvature. So a good direction to move in is one with a high ratio of gradient to curvature, even if the gradient itself is small.

- How can we find directions like these?

Newton’s method

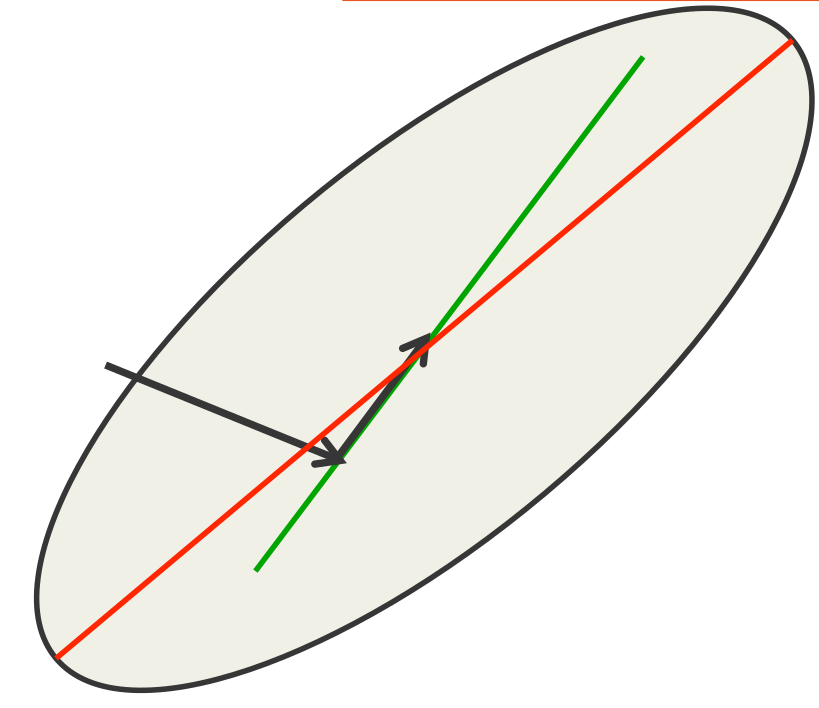

- The basic problem with steepest descent on a quadratic error surface is that the gradient is not the direction we want to go in.

- If the error surface has circular cross-sections, the gradient is fine.

- So lets apply a linear transformation that turns ellipses into circles.

- Newton’s method multiplies the gradient vector by the inverse of the curvature matrix, H

\Delta w = − \epsilon H(w)^{-1}\frac{dE}{dw}dw

- On a real quadratic surface it jumps to the minimum in one step.

- Unfortunately, with only a million weights, the curvature matrix has a trillion terms and it is totally infeasible to invert it.

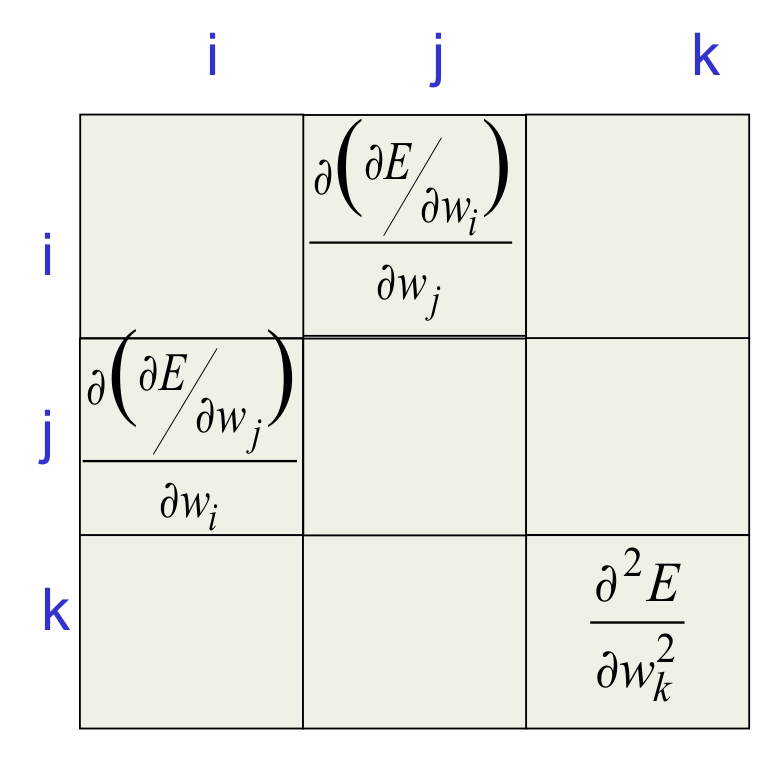

Curvature Matrices

- Each element in the curvature matrix specifies how the gradient in one direction changes as we move in some other direction.

- The off-diagonal terms correspond to twists in the error surface.

- The reason steepest descent goes wrong is that the gradient for one weight gets messed up by the simultaneous changes to all the other weights.

- The curvature matrix determines the sizes of these interactions.

How to avoid inverting a huge matrix

- The curvature matrix has too many terms to be of use in a big network.

- Maybe we can get some benefit from just using the terms along the leading diagonal (Le Cun). But the diagonal terms are only a tiny fraction of the interactions (they are the self-interactions).

- The curvature matrix can be approximated in many different ways

- Hessian-free methods, LBFGS, ….

- In the HF method, we make an approximation to the curvature matrix and then, assuming that approximation is correct, we minimize the error using an efficient technique called conjugate gradient. Then we make another approximation to the curvature matrix and minimize again.

- For RNNs its important to add a penalty for changing any of the hidden activities too much.

Conjugate gradient

- There is an alternative to going to the minimum in one step by multiplying by the inverse of the curvature matrix.

- Use a sequence of steps each of which finds the minimum along one direction.

- Ensure that each new direction is “conjugate” to the previous directions so you do not mess up the minimization you already did.

- “conjugate” means that as you go in the new direction, you do not change the gradients in the previous directions.

A picture of conjugate gradient

- The gradient in the direction of the first step is zero at all points on the green line.

- So if we move along the green line we don’t mess up the minimization we already did in the first direction.

What does conjugate gradient achieve?

- After N steps, conjugate gradient is guaranteed to find the minimum of an N-dimensional quadratic surface. Why?

- After many less than N steps it has typically got the error very close to the minimum value.

- Conjugate gradient can be applied directly to a non-quadratic error surface and it usually works quite well (non-linear conjugate grad.)

- The HF optimizer uses conjugate gradient for minimization on a genuinely quadratic surface where it excels.

- The genuinely quadratic surface is the quadratic approximation to the true surface.

Lecture 8b Modeling character strings with multiplicative connections

Modeling text: Advantages of working with characters

- The web is composed of character strings.

- Any learning method powerful enough to understand the world by reading the web ought to find it trivial to learn which strings make words (this turns out to be true, as we shall see).

- Pre-processing text to get words is a big hassle

- What about morphemes (prefixes, suffixes etc)

- What about subtle effects like “sn” words?

- What about New York?

- What about Finnish: ymmartamattomyydellansakaan

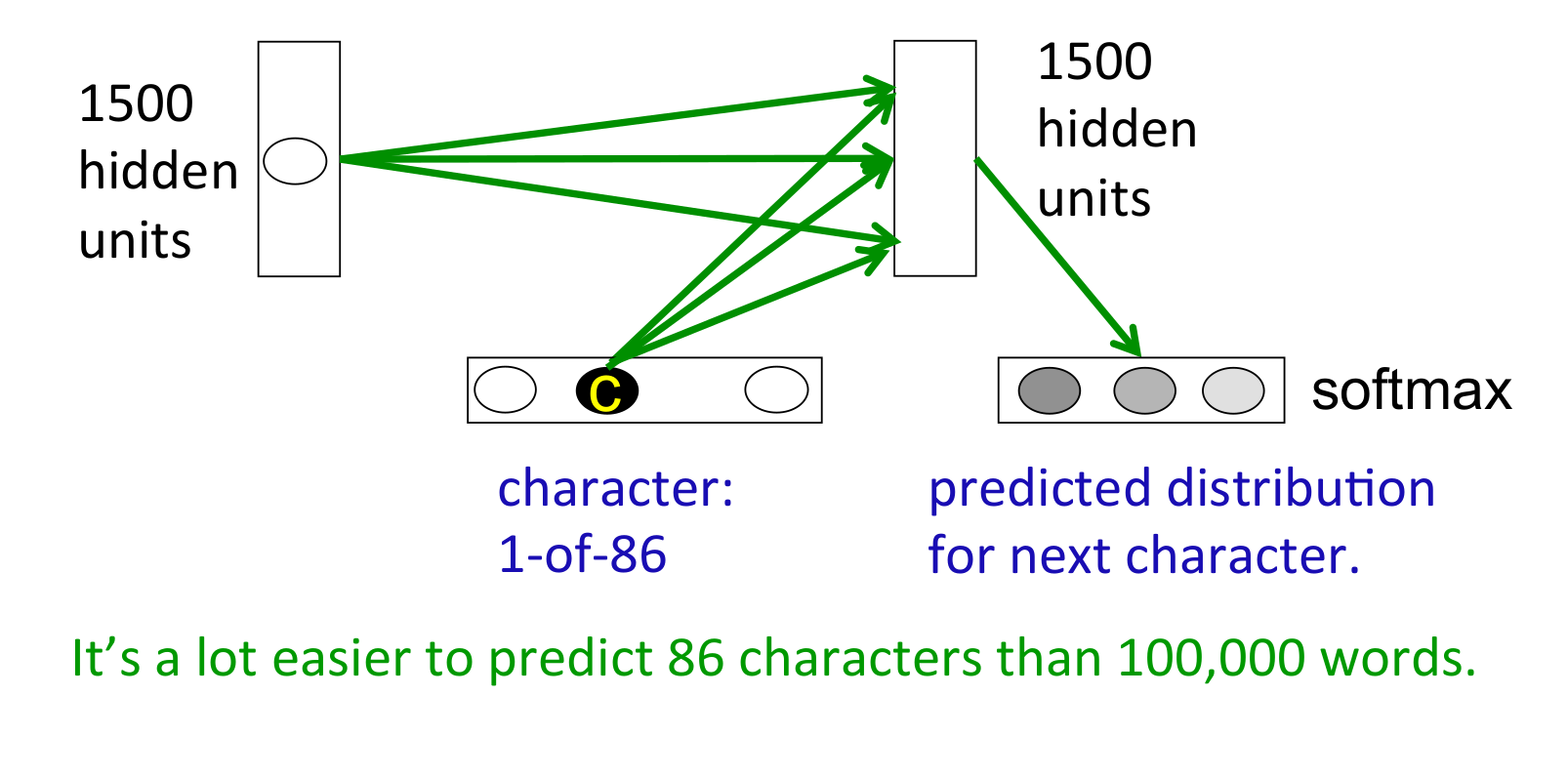

An obvious recurrent neural net

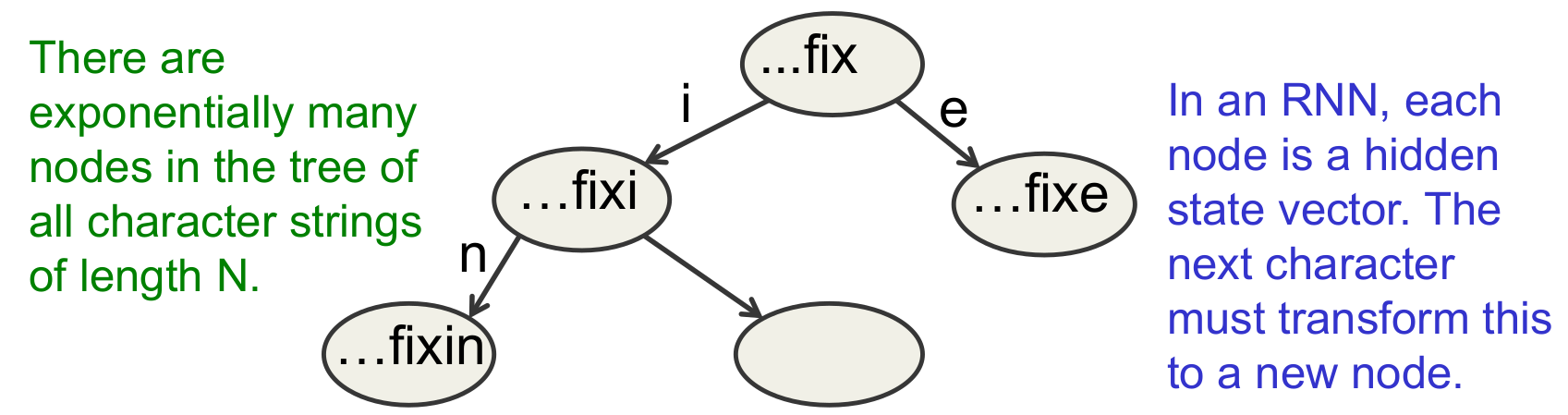

A sub-tree in the tree of all character strings

- If the nodes are implemented as hidden states in an RNN, different nodes can share structure because they use distributed representations.

- The next hidden representation needs to depend on the conjunction of the current character and the current hidden representation

Multiplicative connections

- Instead of using the inputs to the recurrent net to provide additive extra input to the hidden units, we could use the current input character to choose the whole hidden-to-hidden weight matrix.

- But this requires 86x1500x1500 parameters

- This could make the net overfit.

- Can we achieve the same kind of multiplicative interaction using fewer parameters?

- We want a different transition matrix for each of the 86 characters, but we want these 86 character-specific weight matrices to share parameters (the characters 9 and 8 should have similar matrices).

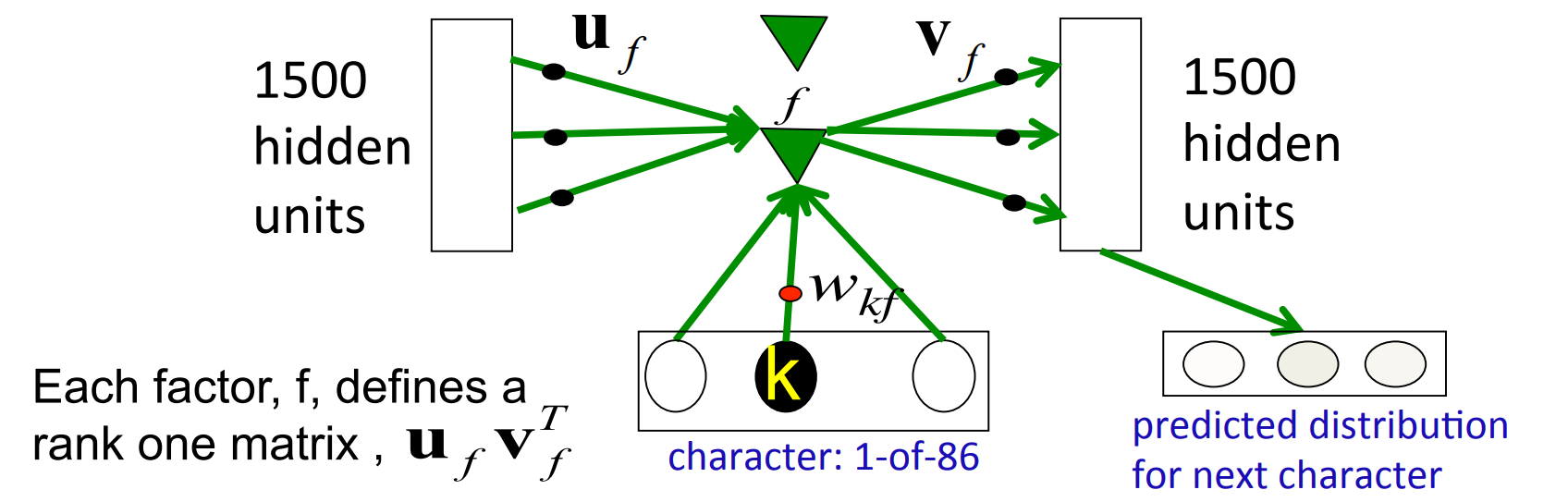

Using factors to implement multiplicative interactions

- We can get groups a and b to interact multiplicatively by using “factors”.

- Each factor first computes a weighted sum for each of its input groups.

- Then it sends the product of the weighted sums to its output group.

\begin{aligned} \color{blue}{c_f} &= \color{red}{(b^T w_f)}\color{green}{(a^T a_f)} v_f \end{aligned} - bkue - vector of inputs to group c - red - scalar input to f from group b - green - scalar input to f from group a

Using factors to implement a set of basis matrices

- We can think about factors another way:

- Each factor defines a rank 1 transition matrix from a to c.

\begin{aligned} c_f &= (b^T w_f)(a^T a_f)v_f \\ c_f &= \color{purple}{(b^T w_f)}\color{pink}{(u_fv_f^T)}a \\ c &= \big(\sum_f(b^T w_f)(u_f v_f^T)\big)a \end{aligned}

- purple - scaler coefficient

- pink - outer product transition matrix with rank 1

Using 3-way factors to allow a character to create a whole transition matrix

Each character, k, determines a gain w_{kf} for each of these matrices.

Lecture 8c: Learning to predict the next character using HF

Training the character model

- Ilya Sutskever used 5 million strings of 100 characters taken from wikipedia. For each string he starts predicting at the 11th character.

- Using the HF optimizer, it took a month on a GPU board to get a really good model.

- Ilya’s current best RNN is probably the best single model for character prediction (combinations of many models do better).

- It works in a very different way from the best other models.

- It can balance quotes and brackets over long distances. Models that rely on matching previous contexts cannot do this.

How to generate character strings from the model

- Start the model with its default hidden state.

- Give it a “burn-in” sequence of characters and let it update its hidden state after each character.

- Then look at the probability distribution it predicts for the next character.

- Pick a character randomly from that distribution and tell the net that this was the character that actually occurred.

- i.e. tell it that its guess was correct, whatever it guessed.

- Continue to let it pick characters until bored.

- Look at the character strings it produces to see what it “knows”.

He was elected President during the Revolutionary War and forgave Opus Paul at Rome. The regime of his crew of England, is now Arab women’s icons in and the demons that use something between the characters‘ sisters in lower coil trains were always operated on the line of the ephemerable street, respectively, the graphic or other facility for deformation of a given proportion of large segments at RTUS). The B every chord was a “strongly cold internal palette pour even the white blade.”

Some completions produced by the model

- Sheila thrunges (most frequent)

- People thrunge (most frequent next character is space)

- Shiela, Thrungelini del Rey (first try)

- The meaning of life is literary recognition. (6th try)

- The meaning of life is the tradition of the ancient human reproduction: it is less favorable to the good boy for when to remove her bigger. (one of the first 10 tries for a model trained for longer).

What does it know?

- It knows a huge number of words and a lot about proper names, dates, and numbers.

- It is good at balancing quotes and brackets.

- It can count brackets: none, one, many

- It knows a lot about syntax but its very hard to pin down exactly what form this knowledge has.

- Its syntactic knowledge is not modular.

- It knows a lot of weak semantic associations

- E.g. it knows Plato is associated with Wittgenstein and cabbage is associated with vegetable.

RNNs for predicting the next word

- Tomas Mikolov and his collaborators have recently trained quite large RNNs on quite large training sets using BPTT.

- They do better than feed-forward neural nets.

- They do better than the best other models.

- They do even better when averaged with other models.

- RNNs require much less training data to reach the same level of performance as other models.

- RNNs improve faster than other methods as the dataset gets bigger.

- This is going to make them very hard to beat.

Lecture 8d: Echo state networks

The key idea of echo state networks (perceptrons again?)

- A very simple way to learn a feedforward network is to make the early layers random and fixed.

- Then we just learn the last layer which is a linear model that uses the transformed inputs to predict the target outputs.

- A big random expansion of the input vector can help.

- The equivalent idea for RNNs is to fix the input \to hidden connections and the hidden \to hidden connections at random values and only learn the hidden \to output connections.

- The learning is then very simple (assuming linear output units).

- Its important to set the random connections very carefully so the RNN does not explode or die.

Setting the random connections in an Echo State Network

- Set the hidden \to hidden weights so that the length of the activity vector stays about the same after each iteration.

- This allows the input to echo around the network for a long time.

- Use sparse connectivity (i.e. set most of the weights to zero).

- This creates lots of loosely coupled oscillators.

- Choose the scale of the input \to hidden connections very carefully.

- They need to drive the loosely coupled oscillators without wiping out the information from the past that they already contain.

- The learning is so fast that we can try many different scales for the weights and sparsenesses.

- This is often necessary.

A simple example of an echo state network

INPUT SEQUENCE

A real-valued time-varying value that specifies the frequency of a sine wave.

TARGET OUTPUT SEQUENCE

A sine wave with the currently specified frequency.

LEARNING METHOD

Fit a linear model that takes the states of the hidden units as input and produces a single scalar output.

Beyond echo state networks

- Good aspects of ESNs Echo state networks can be trained very fast because they just fit a linear model.

- They demonstrate that its very important to initialize weights sensibly.

- They can do impressive modeling of one-dimensional time-series.

- but they cannot compete seriously for high-dimensional data like pre-processed speech.

- Bad aspects of ESNs They need many more hidden units for a given task than an RNN that learns the hidden \to hidden weights.

- Ilya Sutskever (2012) has shown that if the weights are initialized using the ESN methods, RNNs can be trained very effectively.

- He uses rmsprop with momentum

Reuse

Citation

@online{bochman2017,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {Deep {Neural} {Networks} - {Notes} for {Lesson} 8},

date = {2017-09-11},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/notes/dnn/dnn-08/l_08.html},

langid = {en}

}