Preview

Today we will discuss two other very general AR methods of problem-solving called means end analysis and problem reduction.

Like these two methods, means analysis and problem reduction, are really useful for very well-formed problems.

Not all problems are well-formed. But some problems are. And then these methods are very useful. These three methods, generate-and-test, means-ends analysis, form reduction, together with semantic networks as a knowledge representation, form the basic unit of all fundamental topics in this course.

We’ll begin with the notion of state spaces. Then talk about means-end analysis.

Then we’ll illustrate means-end analysis as a matter for solving problems and then we’ll move onto the method of problem reduction.

Exercise The Block Problem

To understand a method of means and analysis. Let us look at this blocks word problem. This is a very famous problem in AI. It has occurred again and again. And almost every textbook in AI has this problem. You’re given a table on which there are three blocks. And A is on table, B is on table, and C is on A. This is the initial state. And you want to move these blocks, to the gold state. On this configuration, so that C is on table, B is on C and

A is on B. The problem looks very simple listen, doesn’t it?

Let’s introduce a couple of constraints.

You may move only one block at a time, so you can’t pick both A and B together.

And second, you may only move a block that has nothing on top of it. So, you cannot move block A in this configuration, because it has C on top of it.

Let us also suppose that we’re given some operators in this world.

These operators essentially move some object to some location. For example, we could move C to the table, or C onto B, or C onto A.

Not all the operators may be applicable in the current state. C is already on A, but in principle, all these, all of these operators are available. Given these operators, and this initial state and this goal state, write a sequence of operations that will move the blocks from the initial state to the goal state.

Exercise The Block Problem

That’s a good answer, David, that’s a correct answer.

Now the question becomes how can we make in AI agent that will come up with the similar sequence of operations? In particular, how does the matter of means-end analysis work on this problem and come up with a particular sequence of operations?

State Spaces

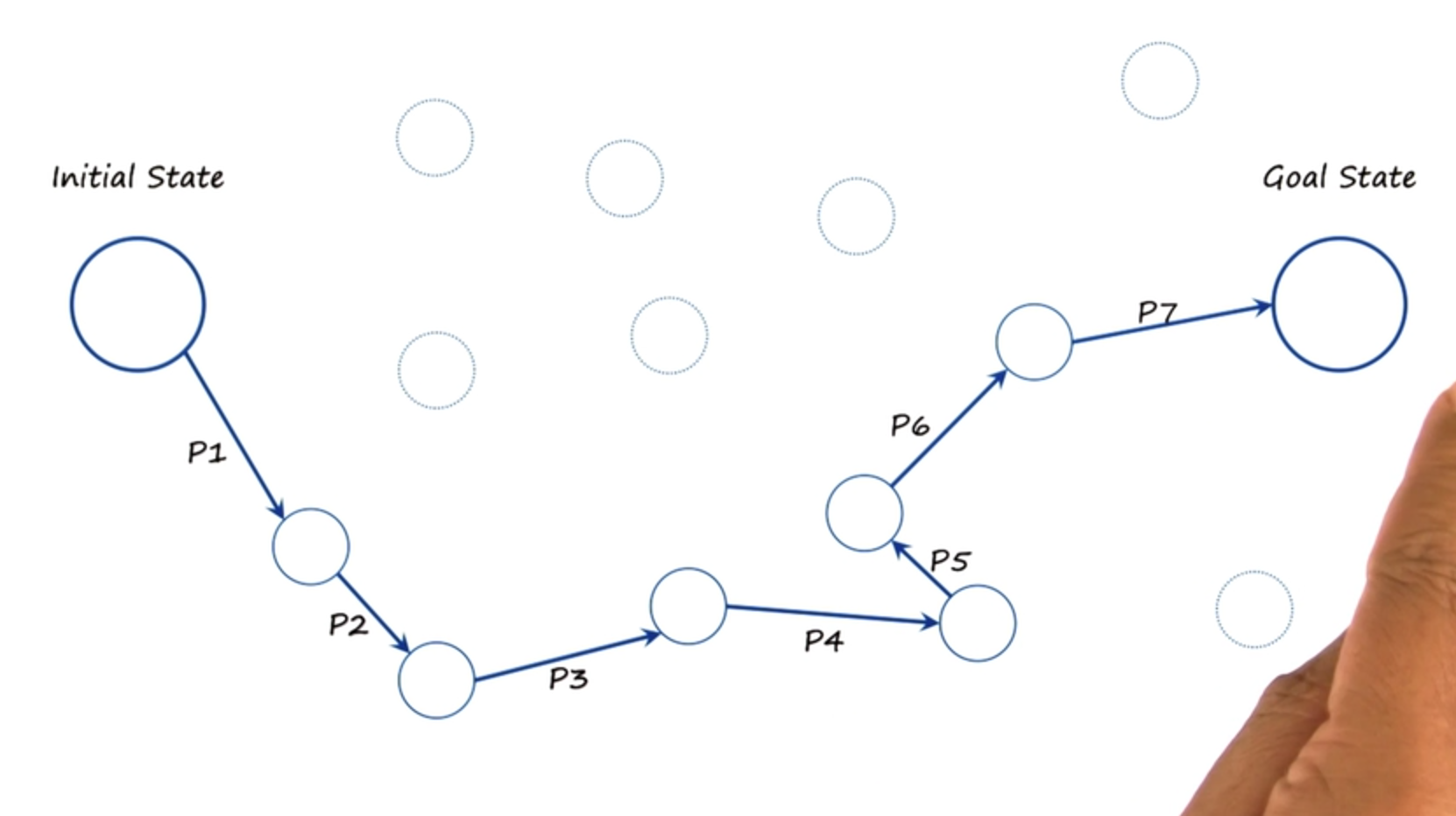

So, we can imagine problem-solving as occurring in a state space.

Here is the initial state, here is the goal state. And the state space consists of all of the states that could be potentially produced from the initial state by iterative application of the various operators in this micro world. I want to come up with a path in the state space, takes me from initial state to the goal state. There is one path, this is not the only path, but this is one path to go from the initial state to the goal state. The question then becomes, how might an AI agent derive this path that may take it from the initial state to the goal state.

Let us see how this notion of path finding applies to our blocks world problem.

From the initial state, here it is one path of going to the goal state. First, we put C on the table. Then we put B on top C. And then we put A on top of B.

Which is exactly the answer that David had given. This is one sequence, one path from the initial state to the goal state. The question then becomes, how does AI method know what operation to select in a given state?

Consider this state, for example. There are several operations possible here.

One could put C on top of B or B on top of A.

How does the AI agent know which operation to select at this particular state?

Differences in State Spaces

One way of thinking about this is to talk in terms of differences. This chart illustrates the differences between different states and the goal state. So, for example, if the current state was this one then this red line illustrates the difference from the goal state. So we should pick an operator that will help reduce the difference between the current state and the goal state.

So the reduction between the difference with the current state and the goal state is the end. The application of the operator is the means.

That’s why it’s called the means-ends analysis. At any given state,

I’m going to pick an operator that will help you deduce the difference between the current state and the goal state. Note in a way this problem is similar to the problem of part finding in robotics, where we have to design a robot that could go from one point to another point in some navigation space.

From my office to your office, for example, if all our offices were in the same building. There too we would use the notion of distances between offices. Here we using the notion of distance in a metaphorical sense, in a figurative sense, not in a physical sense. So I’ll sometimes use the word difference instead of distance but it’s the same idea. We are trying to deduce the distance or the difference but in an abstract space. So going back to an example of going from this initial state to this goal state. I can look at initial state and see that there are three differences between the initial state and the goal state. First, A is on table here, but A should be on B.

B is on table here, but B should be on C. And third, C is on top of A here, the C should be on top, on table there. So three differences. Here the number of operations are available to us. Nine operations in particular. Let us do a means- end analysis. We can apply an operator that would put C on table.

In which case the difference between the new state and the goal state will be two. We could apply an operator that will put C on top of B, in that case the difference between the current state and the goal state will still be three. Or we can apply the operator putting B on top of C, in which case the distance between the current state and the goal state will be 2. Notice that the notion of reducing differences now leads to two possible choices. One could go with this state or with this one.

Means-end analysis by itself does not help an AI agent decide between this course of action and that course of action. This is something that we will return to, both a little bit later in this lesson and even much more in detail when we come to planning in this course. For now, let us resume that we choose the top course of action just like they had done already there. So this chart illustrates the pot taken from the initial state to the goal state.

And the important thing to notice here is that with each different move the distance between the current state and the goal state is decreasing, from three to two to one to zero. This is why means-end analysis comes up with this path because at each time it reduces a difference

Process of Means End Analysis

We can summarize the means-ends analysis method like this.

Compare the current state and the goal state. Find the differences between them. For each difference, look at what operators might be applicable. Select that operator that gets you closest to the goal state from the current state. We did this for the blocks and worlds problem. We also did this with regards to the business problem. But throughout those states in regards to business problem, which we’re not getting us close to the goal state. This is the means-ends analysis method in summary.

Exercise Block Problem I

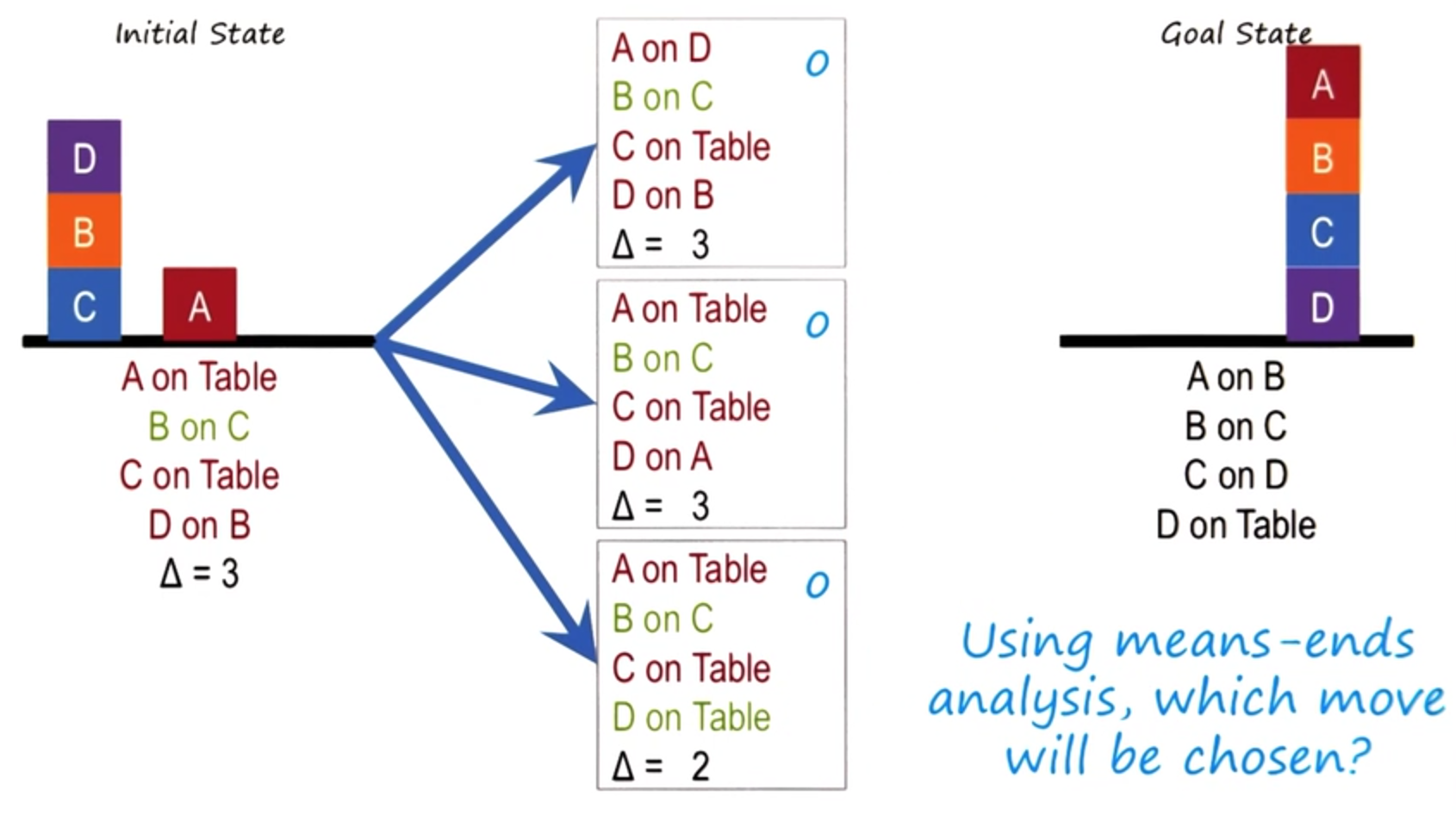

To understand more deeply the properties of means and analysis, let us look at another, slightly more complicated example. In this example, there are four blocks instead of the three in the previous example. A, B,

C, D. In the initial state, the blocks are arranged as shown here.

The goal state is shown here on the right. The four blocks are arranged in a particular order. Now if you compare the configuration of blocks on the left with the configuration of blocks on the right, in the goal state, you can see there are three differences. First, A is on Table, where A is on B here. B is on C. That’s not a difference. C is on Table.

C is on D here, D’s on B, D’s on Table here. So there are three differences.

So, this is a heuristic measure of the difference between the initial state and the goal state. Once again, we’ll assume that the AI agent can move only one block at a time.

Given the specification of the problem, what states are possible from the initial state? Please write down your answers in these boxes.

Exercise Block Problem I

That’s good David.

Exercise Block Problem II

Okay now for each of these states that is possible from the initial state what are the differences as compared to the goal state?

Please write down your answers in these boxes.

Exercise Block Problem II

Good, David. So in each state David is comparing the state with the goal state and finding differences between them.

Exercise Block Problem III

Given these three choices which operation would means-end analysis choose?

Exercise Block Problem III

That’s correct, David

Exercise Block Problem IV

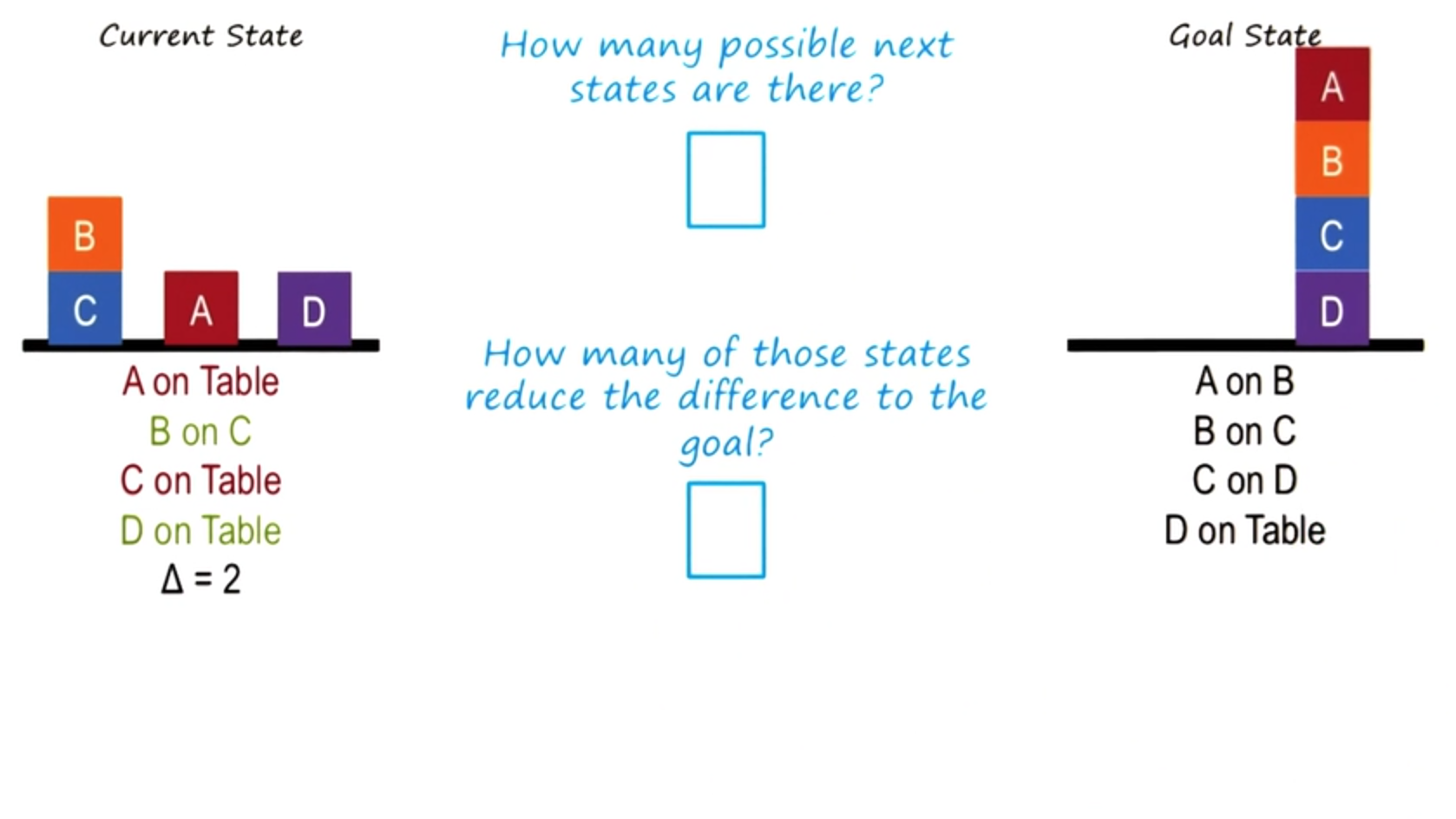

Given this current state, we can apply means ends analysis veritably.

Now, if we apply means on some of those to this particular state, the number of choices here is very large, so I will not go through all of them here.

But I’d like you to write down the number of possible next states. As well as, how many of those states reduce the difference to the goal? Which is given here.

Exercise Block Problem IV

That’s good, David.

Exercise Block Problem V

So, the operation of putting A on B will bring us to this state.

Given this state, we can have, again, apply a means of analysis. Again, I’m not sure that all these states here, but

I’d like you to find out how many possible states are there and how many of those states reduce the difference to the goal described.

Exercise Block Problem V

That’s right David and that means that means-ends analysis doesn’t not always take us to what’s the goal. Sometimes it can take us away from the goal.

And sometimes means-end analysis can get caught in loops. Means-end analysis, like genetic and test, is an example of universal error methods.

These universal error methods are applicalbe to very large classes of problems.

However, they can rate few guarantees of success, and they’re often very costly. They’re costly in terms of computational efficiency.

They neither provide any guarantees of computational efficiency, nor provide any guarantees of the optimality of the solution that they come up with.

Their power lies in the fact that they can be applied to a very large class of problems. Later in this class, we’ll discuss problem-solving methods, which are very specialized problem-solving methods.

Those methods are applicable to a smaller class of problems. However, they are more tuned to those problems and often are more efficient and sometimes, also provide guarantees over the optimality of the solution.

Although means-end analysis did not work very for this problem. It infact works quite well for many other problems and therefore is an important AI method.

Later in this class when we come to planning, we will look at more powerful specialized methods that can in fact address this class of problems quite well.

Assignment Means-Ends Analysis

So how do you use means ends analysis to solve Raven’s Progressive Matrices?

What exactly is our goal in this context?

You might think of the goal in different ways. We might think of it as, the goal is to solve the problem or in a different sense we might think of the goal as the transform sum frame into another frame. And then trace back and find what the transformation was? In that context how would you then measure distance? We noticed that distance is important in doing means ends analysis because that helps us decide what to do next. Once you have a measure of how to actually measure distance to your goal what are the individual operators or moves that you can take to actually move closer to your goal and how would you weight them to be able to decide what to do at any given time.

In addition, what are the overall strengths of using means and analysis as a problem-solving approach in this context, and what are its limitations. Is it well suited for these problems, or are there perhaps other things that we can be doing that aren’t necessarily under this topic that would actually make the problem even easier.

Problem Reduction

Let us now turn to the third problem-solving method under this topic called problem reduction. The method of problem reduction actually is quite intuitive.

I’m sure you use it all the time. Given the hard complex problem, reduce it.

Decompose it into multiple easier, smaller, simpler problems. Consider, for example, computer programming or software design that I’m sure many of you do all the time. Given a hard part of the address, you decompose it with a series of smaller problems. How do I read the input? How do I process it?

How do I write the output? That itself is a decomposition. In fact, one of the fundamental roles that knowledge plays is it tells you how to decompose a hard problem into simpler problems.

Then once you have solutions to this simpler smaller problems.

You can think about how to compose the sub-solutions to the sub-problems into a solution of the problem as a whole. That’s how problem reduction works.

Problem Reduction in the Block Problem

Let us start from where we left off when we finished [UNKNOWN] analysis.

This was the current state, this was the goal state. As we saw from [UNKNOWN] analysis, achieving this goal state is not a very easy problem.

However, we can think of this goal state as being composed of several sub goals, so D on top of table. C on top of D. B on top of C. A on top of B.

Four sub goals here. Now, we can try to address this problem by looking at one sub goal at a time. Let us suppose that we have picked this sub goal,

C on top of D. Give that sub goal, we can now start from this current state and try to achieve this sub goal. Now of course, one might ask the question, why did we pick the goal C over D, and not the goal, B over C, or the goal A over B?

Well one reason is that, the difference between this state and that state had to do with C over D. But in general, problem reduction by itself does not tell us, what sub-goal to attack first. That is a problem, we’ll address later when we come to planning. Well now the major point is, that we can decompose the goal into several subgoals, and attack one subgoal at a time. Now that we have C over

D as a subgoal, we really don’t carry about whether A is on B or B is on C. What we are focused on is the other two states, C on table, D on table, because those are the blocks that occur in the goal state. So let us now see how [INAUDIBLE] have been solved this sub problem [INAUDIBLE] goal C on D and D on Table.

Exercise Problem Reduction I

So given this is a current state, what successor states are possible if we were to apply means and analysis? Please fill in these boxes.

Exercise Problem Reduction I

That looks right, David.

Exercise Problem Reduction II

Let us now calculate the difference from each of the states to the goal state.

Exercise Problem Reduction II

So note that both the state at the top and this state at the bottom have a equal amount of difference compared to goal state. We could’ve chosen either state to go further. For now, we going to go with the one at the bottom. The reason of course is that if I put A on D that will get in the way of solving the rest of the problem. For now, let us go with this state. Later on we will see how an AI agent will decide that this is not a good path to take and this is the better path to take.

Exercise Problem Reduction III

So if we make the move that we had at the end of the last shot, we’ll get this state. So now we need to go from this state to the goal state.

Please write down what is the sequence of operators which might take us from the current state to the goal state.

Exercise Problem Reduction III

That was the right answer David, thank you. You will note that we leaving several questions unanswered for now and that is fine, but you will also note that this problem reduction helps us make progress towards solving the problem.

Exercise Problem Reduction III

So the application of the last move in the previous shot will bring us to this state. In this state the the sub-goal C over D has been achieved. Now that we’ve achieved the first sub-goal, we can worry about achieving the other sub-goals.

The other sub-goals, recall, were B over C and A over B. Given this as the current state and this as the goal state.

Please write down the sequence of operations that will take us from the current state to the goal state.

Exercise Problem Reduction III

That was correct, David. Now this particular problem might look very simple.

Because for you and me as humans, going from this state to this state is almost trivial. But notice how many different questions arose in trying to analyze this problem. Clearly, you and I as humans must be addressing these issues.

This kind of A.I anaylsis makes explicit what is usually tacit when humans solve this problem. And that is one of the powers of A.I.. Indeed we have left a lot of questions unanswered. But each unanswered question then requires an answer.

Now we know that if you must develop methods that somehow will help to address those questions. Like genetic [x] tests and like [x] dialysis.

Problem reduction is a universal method. It is applicable very large class of problems. Once again, problem reduction does not provide guarantee of successes.

Means-Ends Analysis for Ravens

That’s good analysis, David. Let’s go one step further.

There’s also has generation test on it. We are generated solutions, that we can then test against the various choices that were given to us.

So in this particular problem, you can see means-end analysis working, problem reduction working, and direct link test working.

Often, solving a complex problem requires a combination of error techniques.

At one point, one might use problem reduction, at another point, one might use direct link test, at a third point, one might use means-end analysis. Notice also, that the one single knowledge representation of semantic network, supports all three of these strategies.

The coupling between the knowledge representation and semantic network, and any of these three strategies from reduction, means-end analysis, or generate-and-test, is weak. Late on we’ll come across methods, in which knowledge and the problem-solving method are closely coupled. The knowledge of folds certain inferences. And inferences, demand certain kinds of knowledge.

This is why these methods are known as weak methods. Because the coupling between these universal methods, and the knowledge representation is weak.

Assignment Problem Reduction

So how would you apply a problem reduction to Raven’s Progressive Matrices?

Before we actually talk about how our agents would do it, we can think about how we would do it. When we are solving a matrix, where do the smaller or easier problems that we are actually breaking it down into?

How are we solving those smaller problems, and how are we then combining them into an answer to the problem as a whole? Once we know how we’re doing it, how will your agent actually be able to do the same kind of reasoning process?

How will it recognize when to split a problem in to smaller problems?

How will it solve the smaller problems? And how will it then combine those in to an answer to the problem as whole? During this process think about, what exactly is it that makes these smaller problems easier for your agent to answer than just answering the problem as a whole?

And how does that actually help you solve these problems better?

Wrap Up

So let’s wrap up what we’ve talked about today.

We started off today by talking about state spaces and we used this to frame our discussion of mean-ends analysis. Means-ends analysis is a very general-purpose problem-solving method, that allows us to look at our goal and try to continually move towards it. We then use means-ends analysis to try and address a couple of different kinds of problems. But when we did so, we hit an obstacle. To overcome that obstacle, we used problem reduction.

We can use problem reduction in a lot of other problem-solving contexts, but here we use it to specifically to overcome the obstacle we hit during means-ends analysis. Problem reduction occurs and we take a big hard problem and introduce it into smaller easier problems. By solving the smaller easier problems, we solve the big hard problem. Next time we’re going to talk about production systems, which are the last part of the fundamental areas of our course. But if you’re particularly interested in what we’ve talked about today, you may wish to jump forward to logic and planning. Those were built specifically on the types of the problems we talked about today. And in fact in planning, we’ll see a more robust way of solving the kinds of obstacles that we hit, during our exercise with means and analysis earlier in this lesson.

The Cognitive Connection

Let us examine the connection between methods like means ends analysis and problem reduction on one hand, and human cognition on the other. Methods like means ends analysis, problem reduction and even generate-and-test, are sometimes called weak methods.

They are weak because they make only little use of knowledge. Later on, we’ll look at strong methods that are knowledge intensive. That will demand a lot of knowledge. The good thing about those knowledge intensive methods is, that they will actually use knowledge about the world, to come up with good solutions in an efficient manner. On the other hand, those knowledge intensive methods require knowledge, which is not always available. So humans, when they are working in a domain, in a world at which they are experts, tend to use those knowledge intensive methods because they know a lot about the world. But of course, you and I constantly work in worlds, in domains in which we are not experts. When we’re not an expert in our domain, a domain that might be unfamiliar to us, then we might well go with matters that are weak because they don’t require a lot of knowledge.

Reuse

Citation

@online{bochman2016,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {05 - {Means-End} {Analysis}},

date = {2016-01-29},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/notes/cognitivie-ai-cs7637/05-means-end-analysis/05-means-end-analysis.html},

langid = {en}

}