A large part of this lesson explores solving two types of problems. By using a graph to visually represent the process, we end up with a semantic network. However, it seems that these networks even when implemented in a tool like networks are still unwieldy.

Also, it seems that humans who can solve these problems can come up with networks. But how can a machine come up with a representation etc given just the picture?

This is not discussed and we seem to imagine that the image processing task and Semantic Networks construction is easier than the analogy tasks that the class goes into detail about.

- The SN mixes representation at different levels using a single network, without making the levels and boundaries explicit. For Raven’s matrices, we have :

- A representation of a single matrix - which is fairly complex and challenging to implement 1.

- A representation of a transformation that mutates one matrix into another. 2 3

- A representation that a transformation is a valid hypothesis leading to a solution or that it fails due to some contradiction. 4

- A representation for ranking the best of multiple valid hypotheses. 5

A second shortcoming that makes the SN unwieldy is that it does not seem to treat approach problem-solving in a general fashion. If we have solved a couple of problems using SN are we any closer to solving the third, particularly if they all belong to the same category like Raven’s matrices? But more abstractly there are books

Also if we could encode more of the But there is no common ontology for different problems. The representation does not seem to let us split the annotation of a static state and the process that encodes the transformation between states.

Problem Solving has a rich literature. (Polya and Conway 2014) (Dromey 1982) (De Bono 2002) (Navas 2013) and I am confident that developing an ontology based on problem-solving could allow one to use vocabulary and semantics that will make Semantic networks more general purpose.

Preview

Okay. Let’s get started with Knowledge PCI. Today we’ll talk about semantic networks. This is the kind of knowledge representation scheme. This is the first lesson in our fundamental topics part of the course. We’ll start talking about knowledge representations, then we’ll focus on semantic networks.

We’ll illustrate how semantic networks can be used to address two-by-one matrix problems. You can think of this like a represent and reason modality.

Represent the knowledge, represent the problem, then use that knowledge to address the problem. As simple as that. At the end, we’ll close this lesson by connecting this topic with human cognition and with modern research in AI.

Representations

So what is a knowledge representation?

- The collage on this screen shows several knowledge representations that AI has developed. In each knowledge representation, there is a language. That language has a vocabulary.

Then, in addition to that language, in that knowledge representation, there’s some content. The content of some knowledge. Let’s take an example with which you’re probably already familiar. Consider the Newton’s second law of motion.

So I can represent it as f is equal to m a. This is a knowledge representation.

A very simple knowledge representation, in which there are two things.

There is a language of algebraic equations, y s equal to b x, for example. And then there is the content of our knowledge of Newton’s second law of motion, force equals mass times acceleration.

So the knowledge representation has two things, once again.

The language, which has its vocabulary. For example, this sign of equality. And the content that goes into that representation expressed in that language.

Let us not worry too much about all of the representations in this collage right now, we’ll get to them later. The idea here is to simply show that AI has developed not one, but many knowledge representations.

Each representation has its own affordances and its own constraints.

Introduction to Semantic Networks

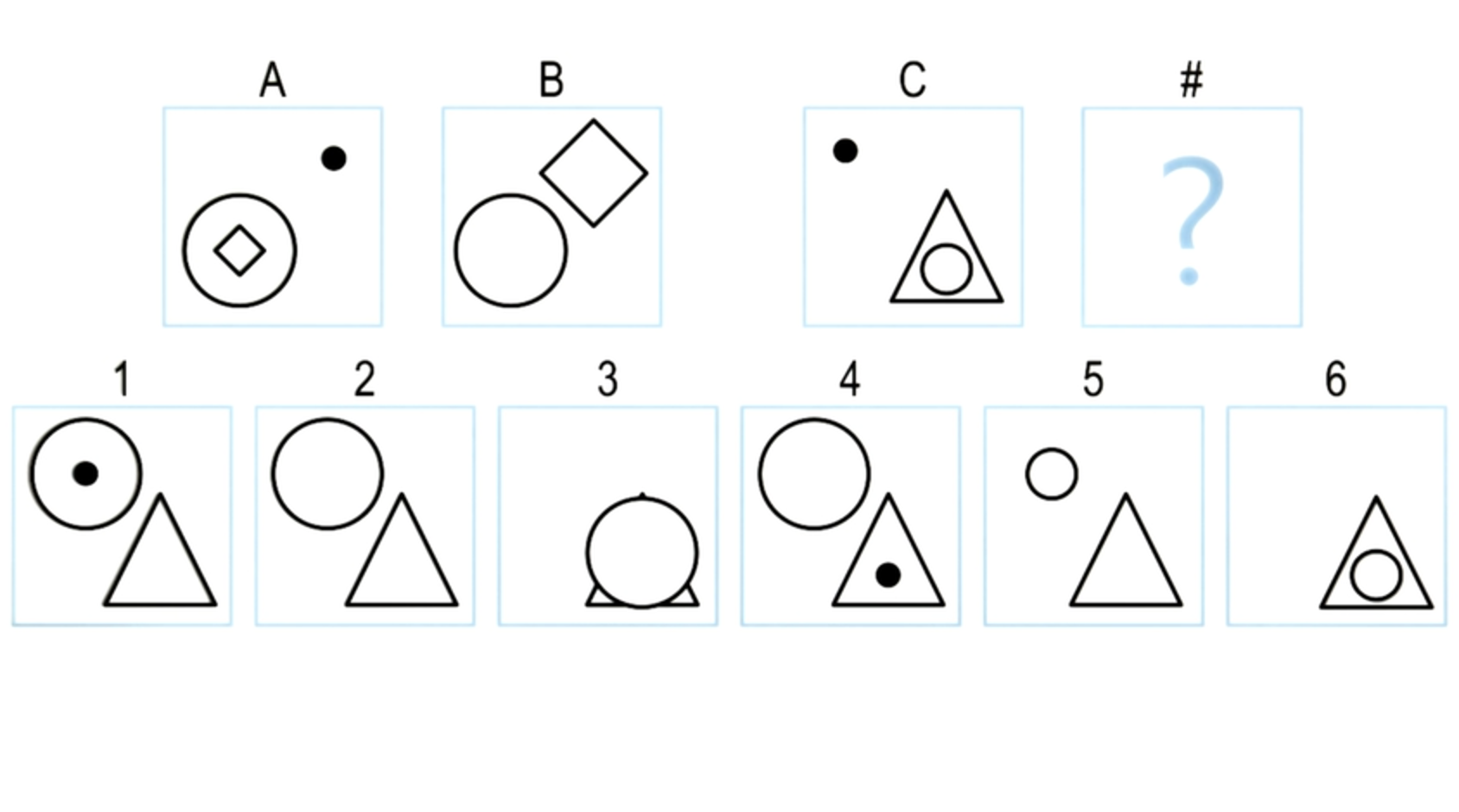

The example above is adapted from Raven’s test of progressive matrices. For further information, see: (John and Raven 2003)

To understand semantic networks as a knowledge representation, let us take an example. This is an example that we saw in a previous lesson.

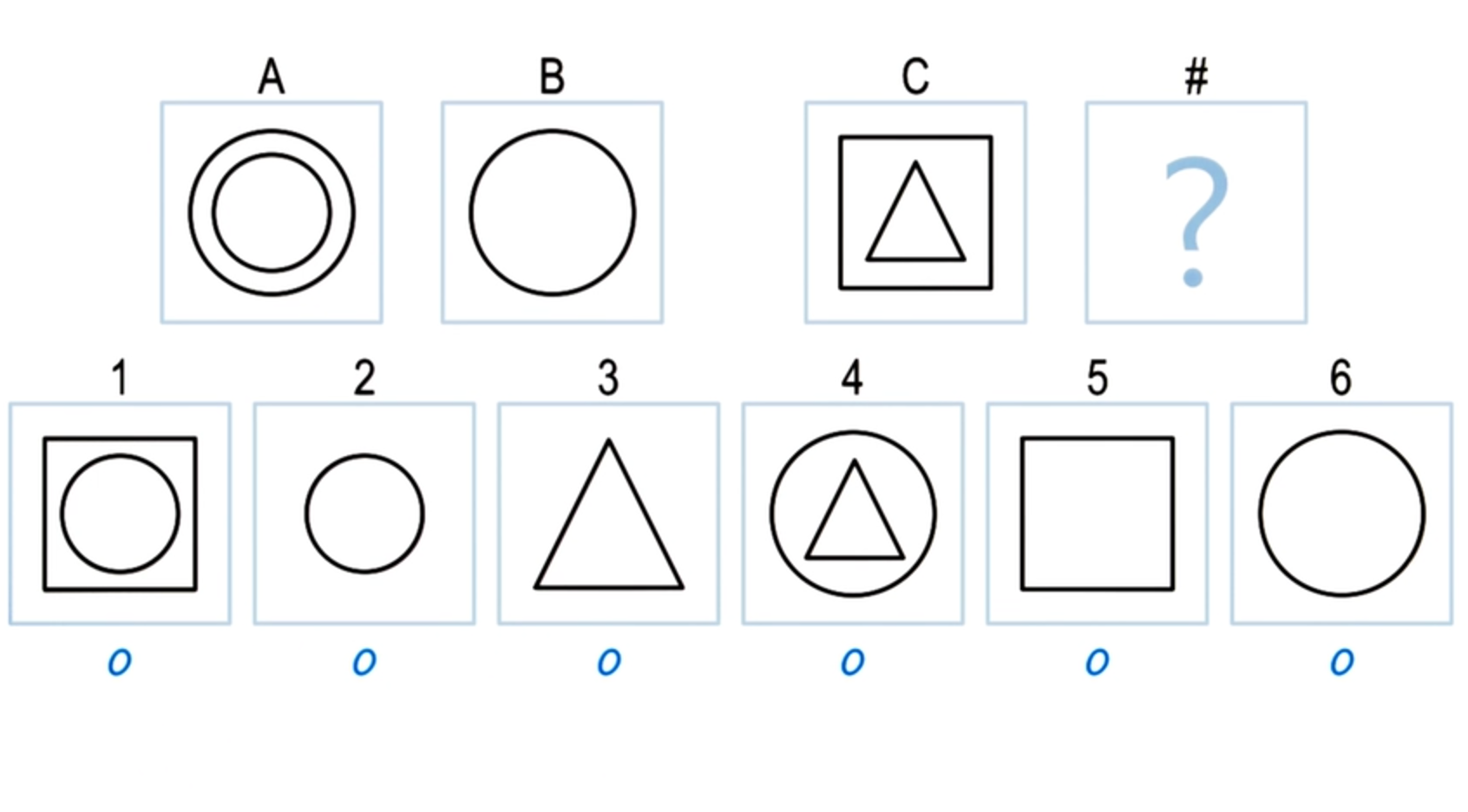

This is A is to B as C is to D, and we have to pick one of the six choices at the bottom that will go in D. How will we represent our knowledge of A,

B, C and the six choices at the bottom? Let us begin with A and B.

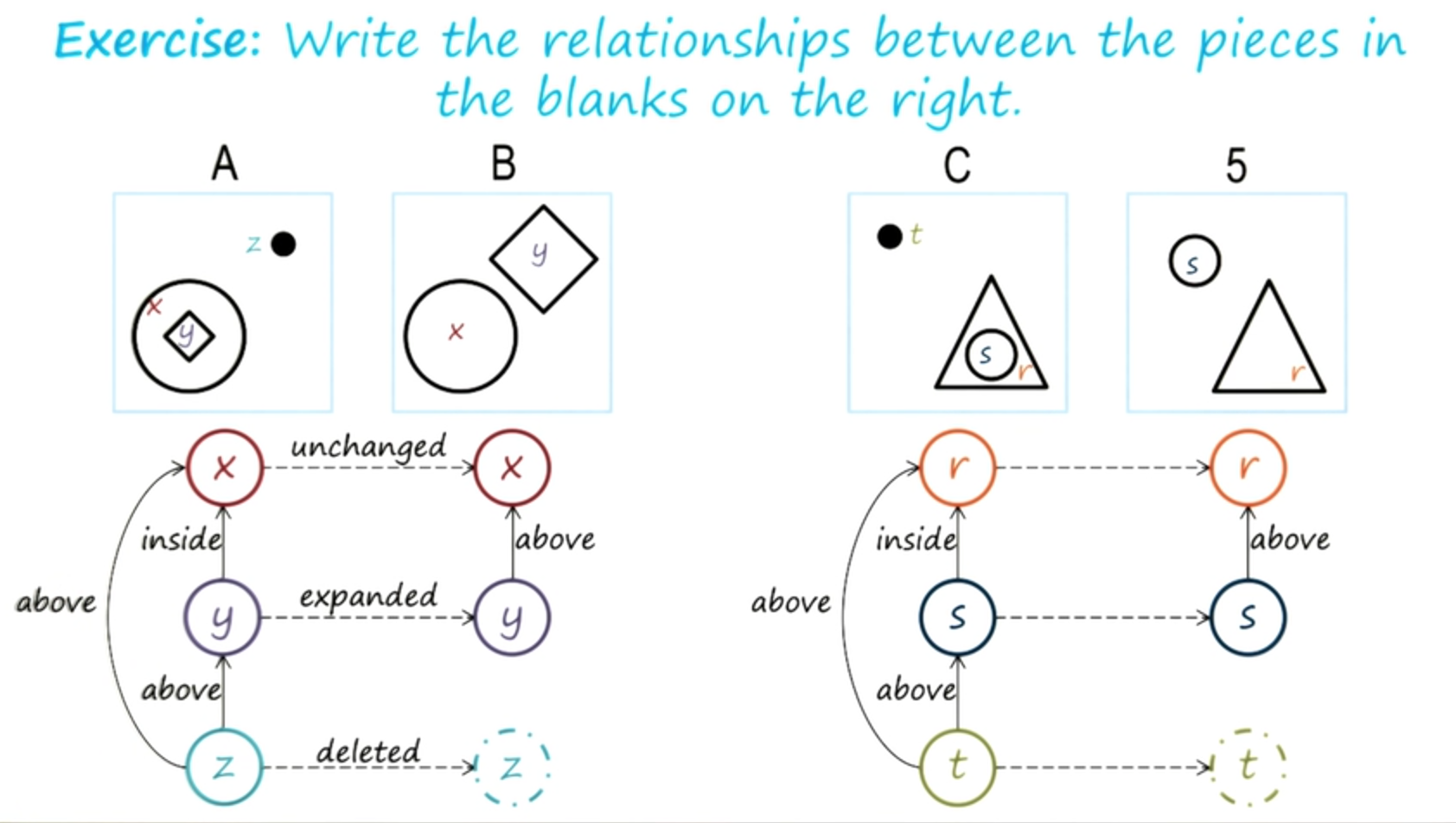

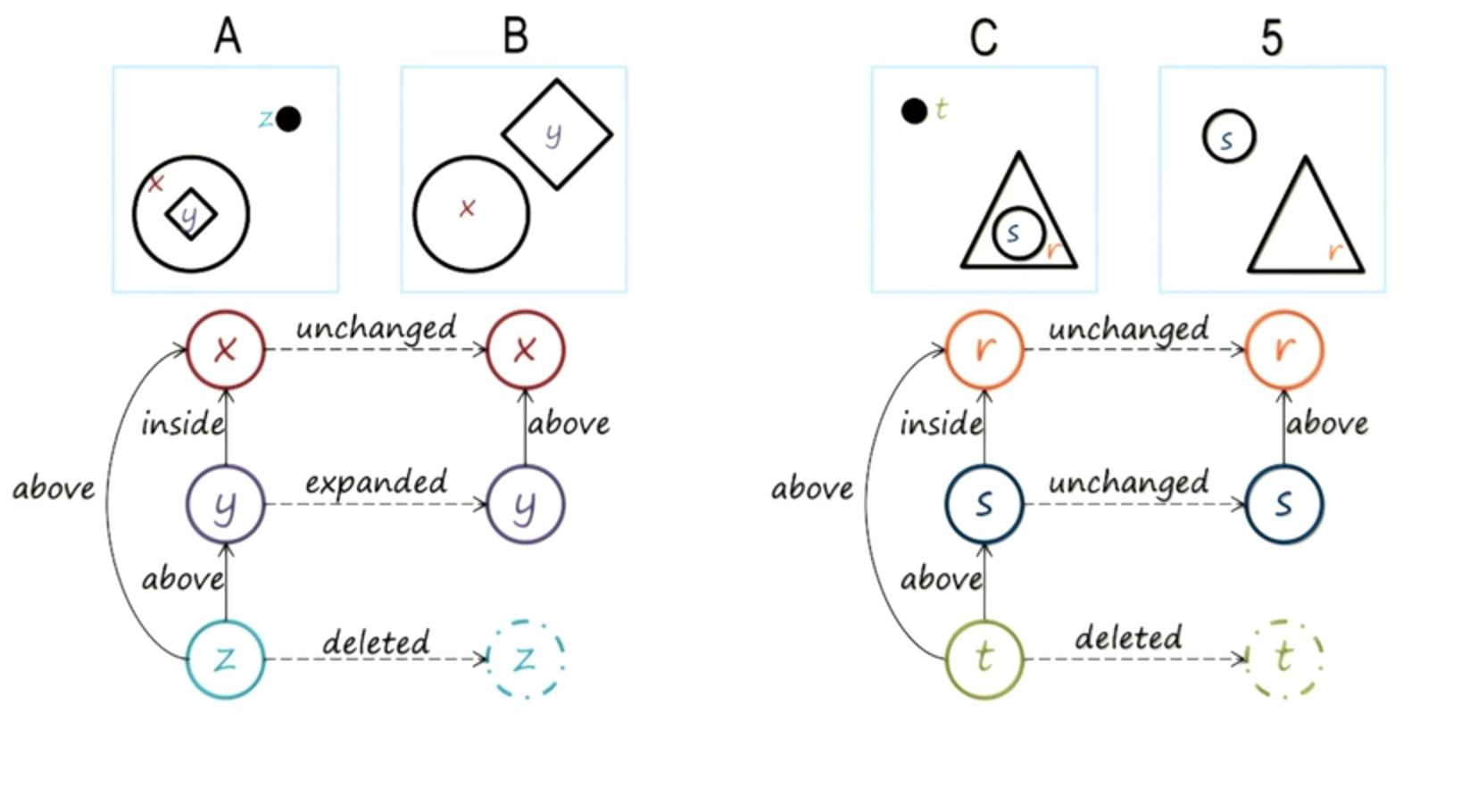

We’ll try to build semantics networks that can represent our knowledge of A and B. Inside A is a circle, I’ll label it x. Also inside x is a diamond, I’ll label it y. Here is a black dot, I’ll label it z.

We can similarly label the objects in B. So inside A are three objects, x, y, and z. So the first thing we need to do in order to build a semantic network for representing our knowledge of A is to represent the object. So I have the object x, the object y, the object z, standing for the circle, the diamond and the black dot. Now that we have represented the objects in A, we want to represent the relationships between these objects. So I have the objects x, y, z, and we’ll try to represent the relationship between them by having links between the nodes representing the objects. These links can be labeled. So I may say that y is inside x because that is the relationship in the image A. Similarly I may say that z is above y because z is above y in the image A.

I may also say that z is above x because z is above x in image A. In this way, a semantic network representation of the image A captures both the objects and the relationship between the objects. We can do exactly the same thing for the image B. The objects and the relationships between them, y is above x. Now that we have represented our knowledge of image A and our knowledge of image B we want to capture somehow the knowledge of the transformation from A to B because recall, A is to B as C is to D.

So we want to capture the relationship between A and B. The transformation from A to B. To do that, to capture the transformation from A to B, we’ll start building links between the objects in A and the objects in B. Now, for x and y they are straightforward for z, but there is no z in b.

So we’ll have a dummy node here in b and we will see how we can label the link here so that we can capture the idea that z doesn’t occur in B. So we might say that x is unchanged because x the circle here is the same as the circle here.

Y on the other hand has expanded. It was a small diamond here and it’s a much bigger diamond there. Z, the black dot, has disappeared all together, so, we have, let’s say, it’s deleted, it’s not there at B at all.

I hope you can see from this example how we constructed a semantic network for the relationship between images A and B. There were three parts to it.

The first part dealt with the objects in A and the object in B.

The second dealt with the relationships between the objects in A and the relationship with the objects in B.

The third-party dealt with the relationships between the objects in A and the relationships between the objects in B. In principle, we can construct semantic networks for much more complicated images, not just A and B.

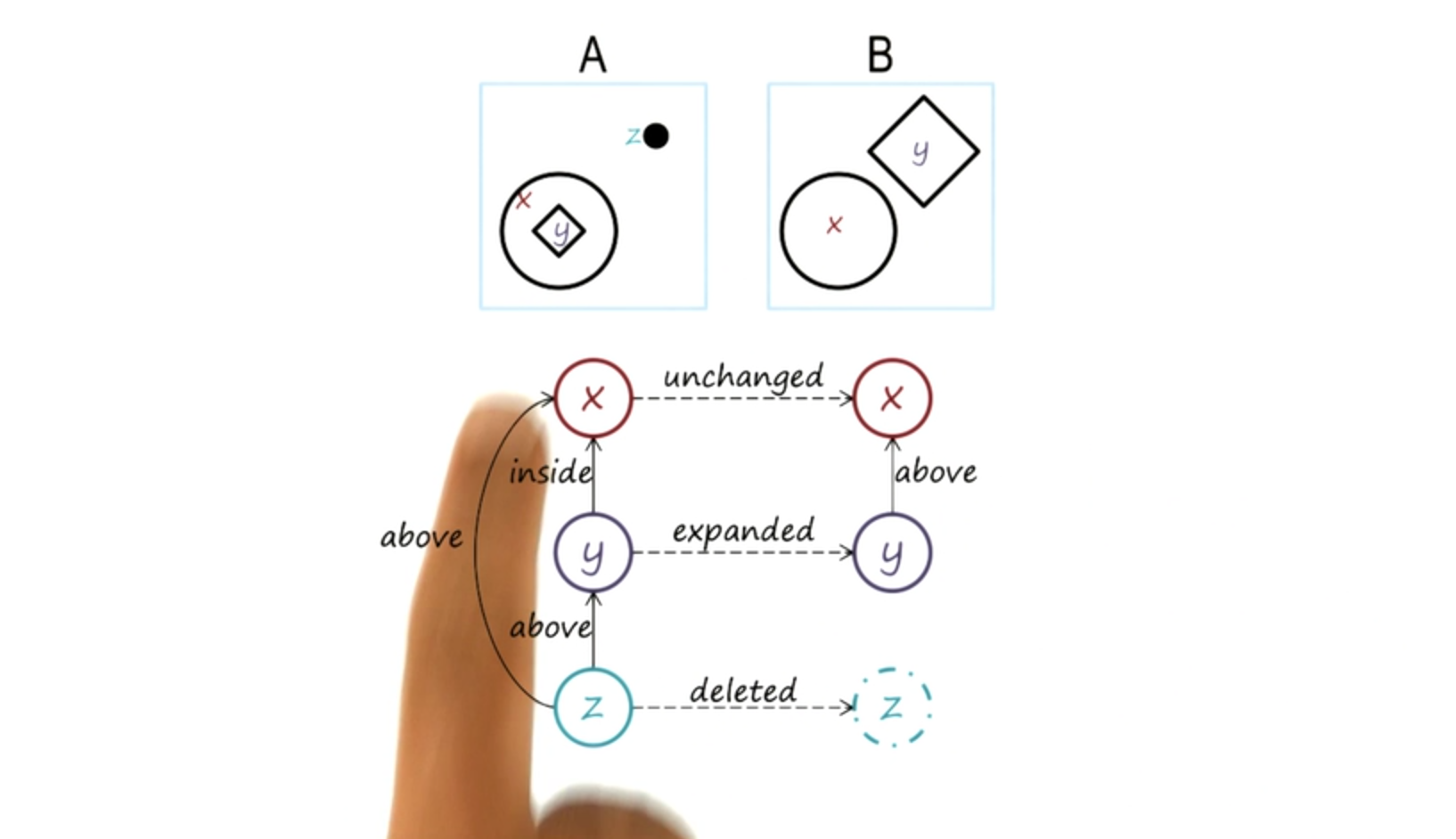

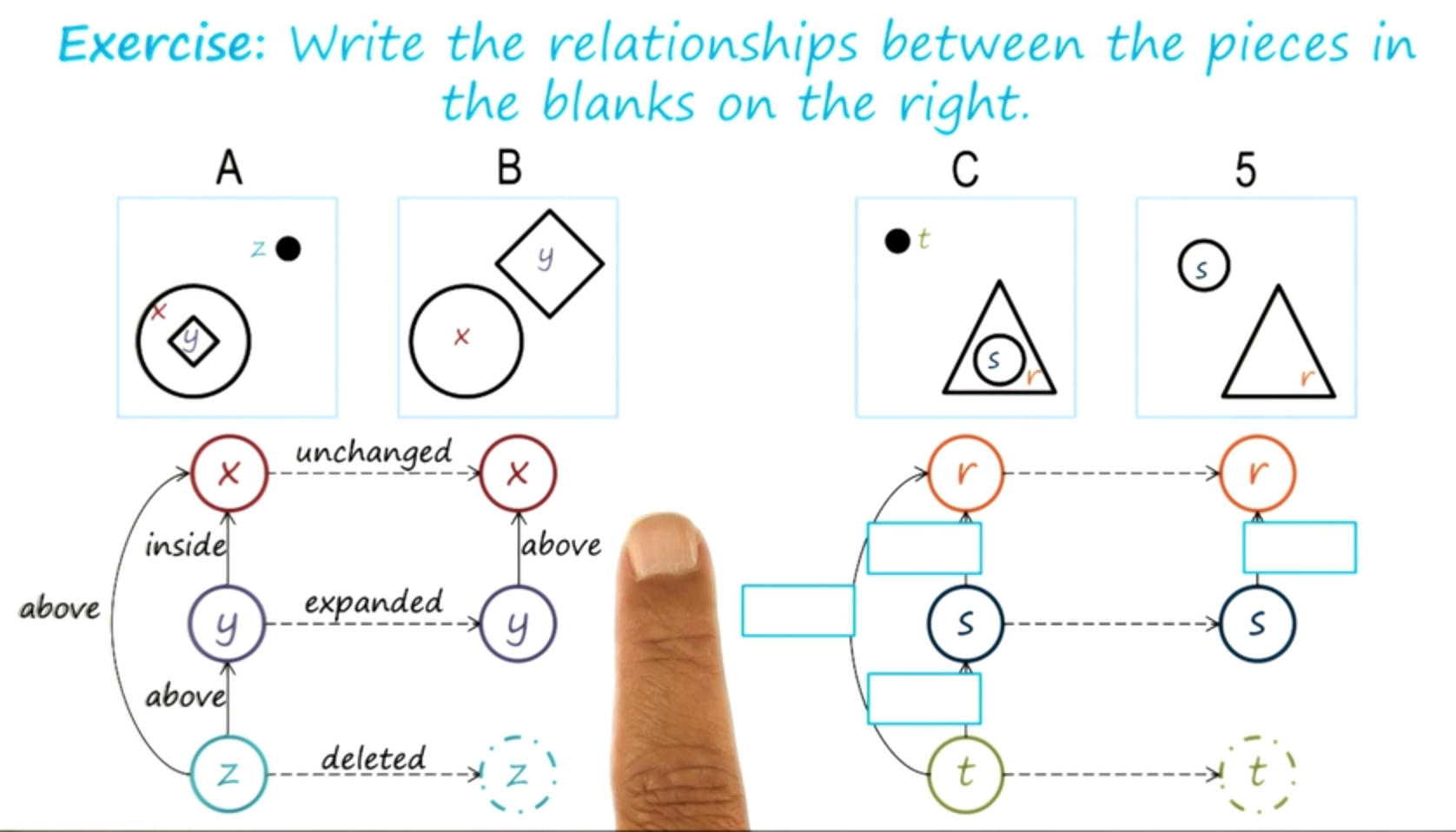

Here is another example of a semantic network for another set of images.

Once again, we have the objects and the relationships. And then the relationship between the objects in the first image and that in the second image.

Exercise Constructing Semantic Nets I

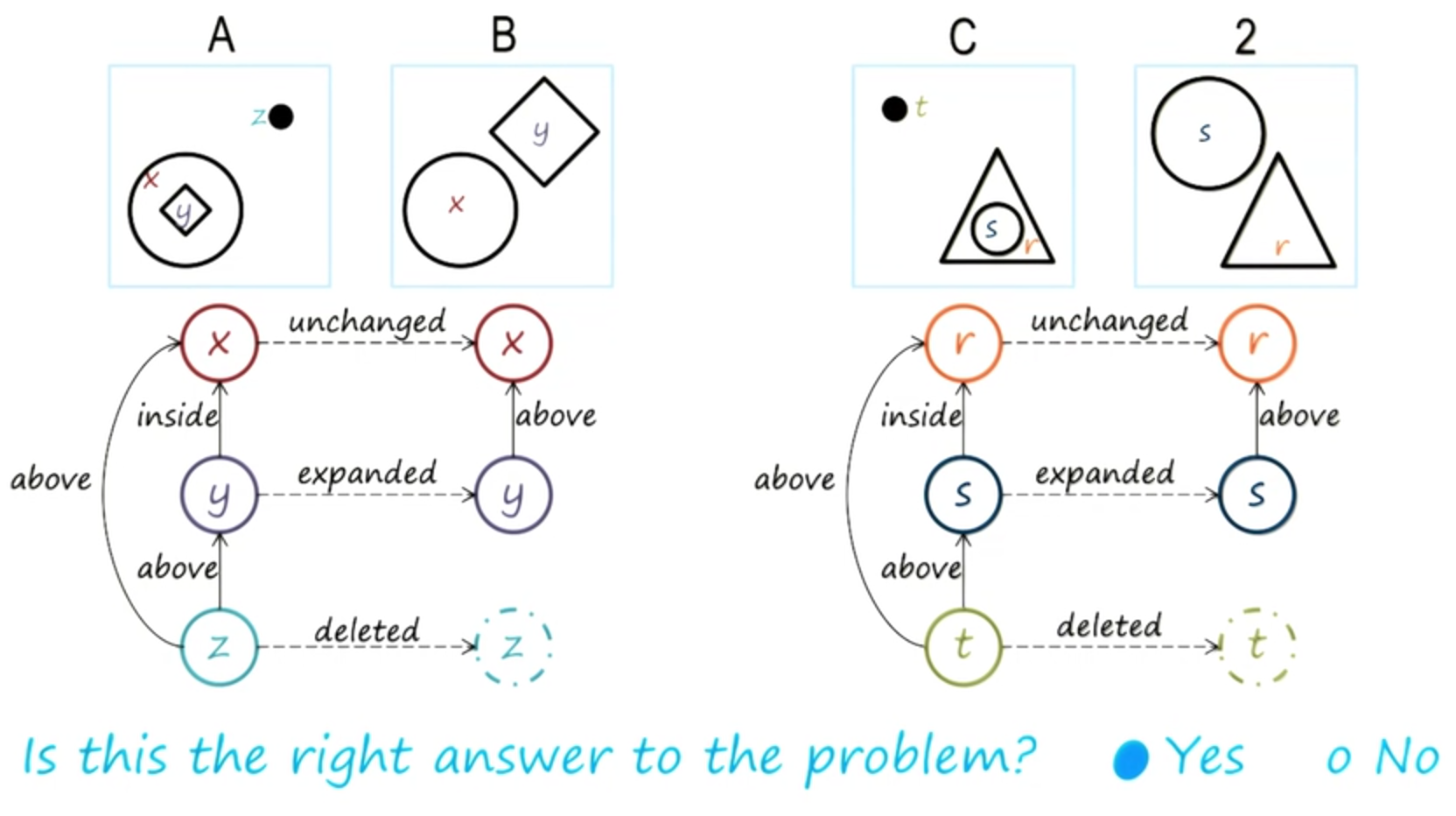

Okay, very good. Here is C and I’ve just chosen one of the choices out of the six choices, five here. And so we’re going to try to build a semantic network for C and five, just the way we built it for A and B. So for C and five, I have already shown all the objects. Now, your task is to come up with labels with the links that are between these objects here, as well as labels for the link between the object for five.

Exercise Constructing Semantic Nets I

Now David made an important point here.

He said that the vocabulary he’s using here inside and above is the same as the vocabulary that I had used inside and above here. And that’s a good point because we want to have a consistent vocabulary throughout the representation of the class of problems. So here we have decided that for representing, problems of this kind in semantic networks, we will use a vocabulary of inside and above and we will try to use it consistently.

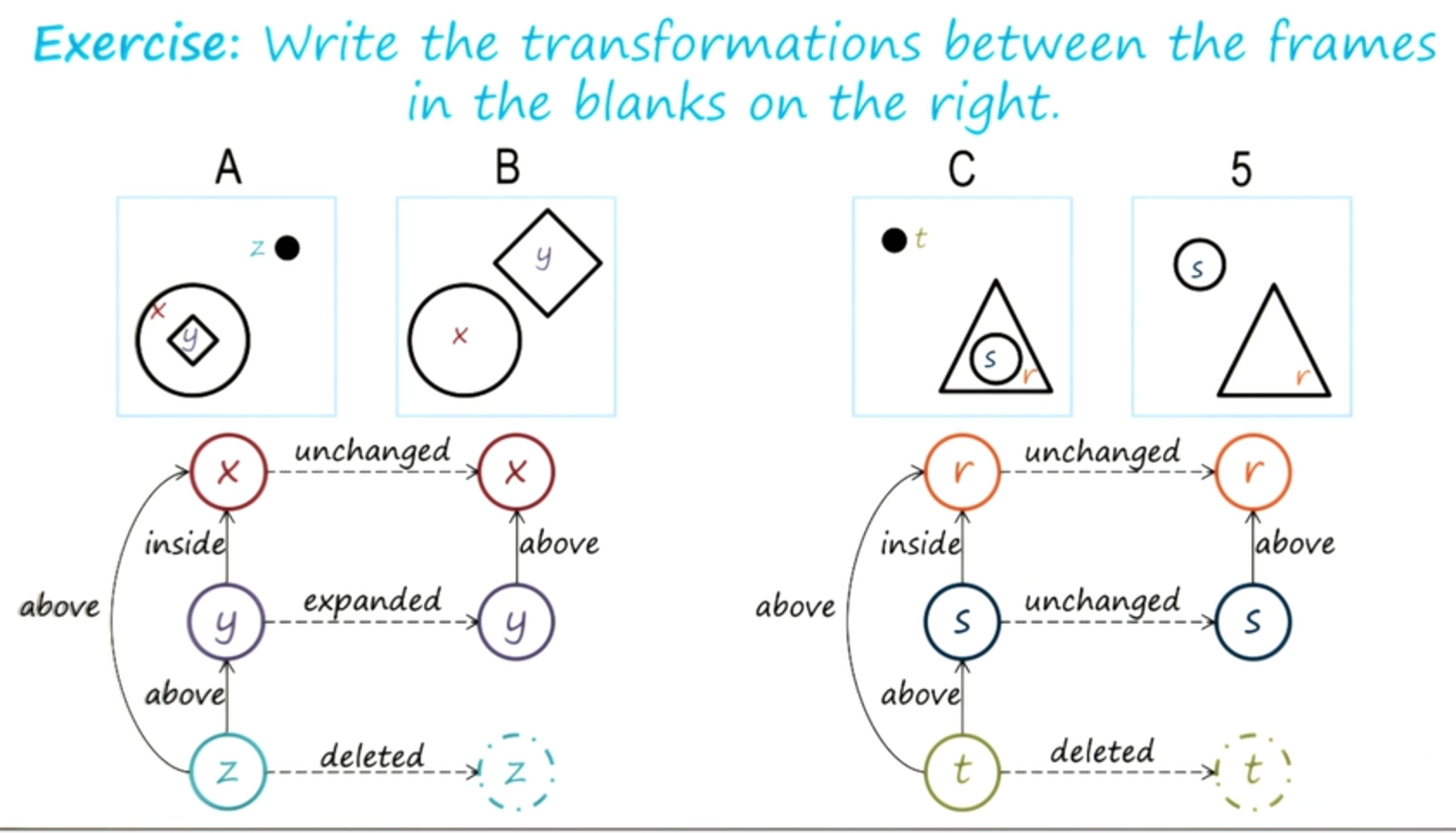

Exercise Constructing Semantic Nets II

Let’s go one step further. Now we have the semantic network for C, and the semantic network for 5. But we have yet to capture the knowledge of the transformation from C to 5. So we have to label the, these three links.

Exercise Constructing Semantic Nets II

Good, that seems like a good answer.

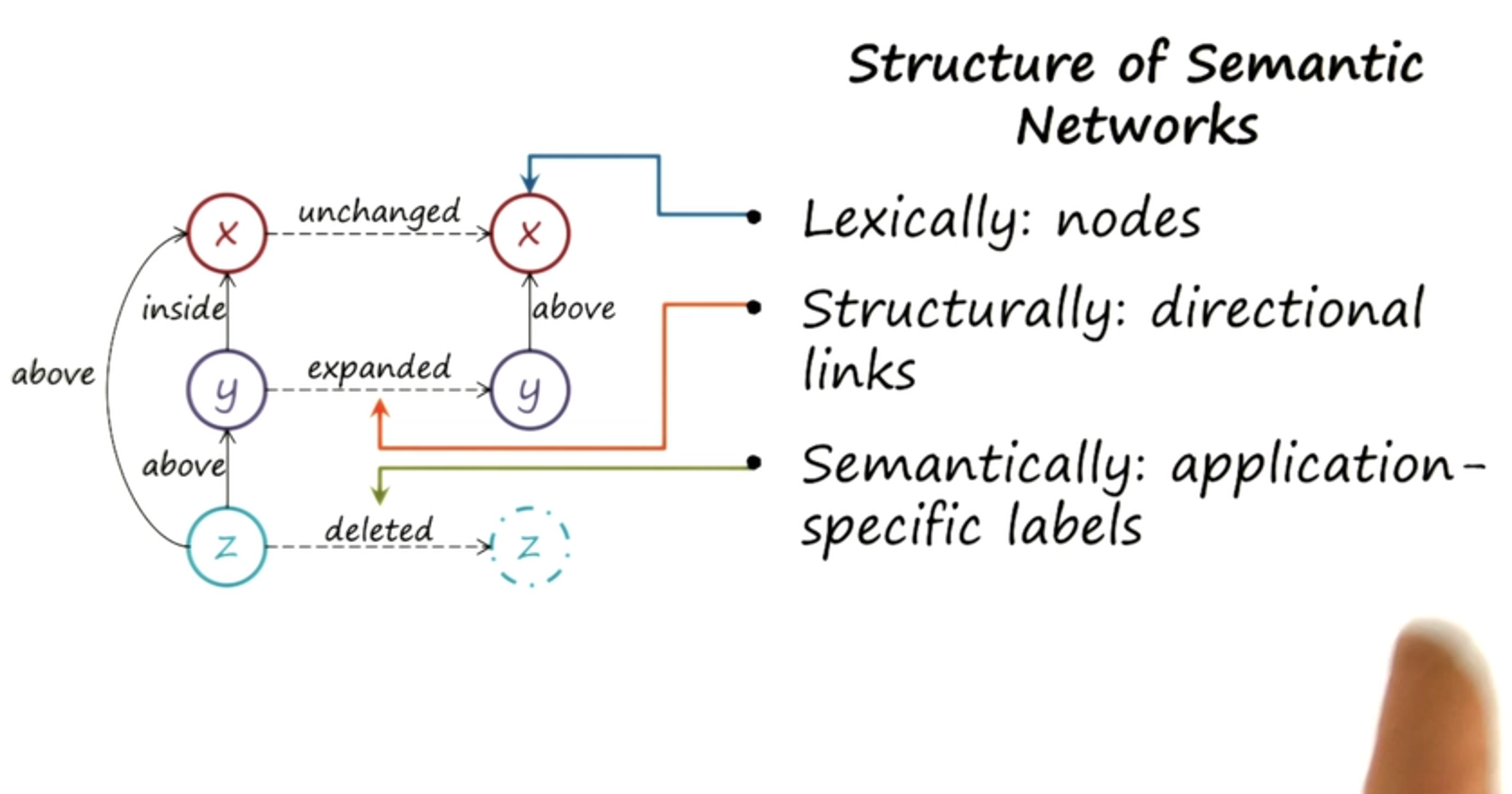

Structure of Semantic Networks

Now that we have seen some examples of semantic networks, let us try to characterize semantic networks as a knowledgeable presentation.

- A lexicon with a vocabulary for encoding the presentation language.

- A structure that tells us about how the words of that vocabulary can be composed together into complex representations

- semantics which tell us how the representation allows us to draw inferences so that we can in fact reason.

In the case of a semantic network:

- the basic lexicon consists of nodes that capture objects. So, x, y, z. What about this structural specification?

- the Structural specification here consists of links with directions that capture the relationships between the nodes. These links let us compose these nodes together into complex representations.

- the semantics are going the labels on these links which are then going to allow us to do, draw inferences and do reasoning over these representations.

Characteristics of Good Representations

Now that we have seen semantic networks in action, we can ask ourselves the important question.

What makes a knowledge representation, a good representation?

Discussion: Good Representations - Quiz

What is a good knowledge representation in everyday life ?

A Nutrition label

Discussion: Good Representations

So note how this connects with the ability to make inferences.

Nutritional labels capture some information that allows us to make good inferences, do not capture all the information

Guards and Prisoners

Let us now look at a different problem, not a 2 by 1 matrix problem but a problem called the guards and prisoners problem. This problem goes by many names, Cannibals and missionaries problem, the jealous husbands problem and so on. It was first seen in a math text book about 880 and has been used by many people in AI for discussing problem representation.

- three guards and three prisoners, must cross to the other bank.

- the boat can only take one or two people at a time.

- prisoners may not outnumber the guards on either bank,

Semantic Networks for “Guards and Prisoners”

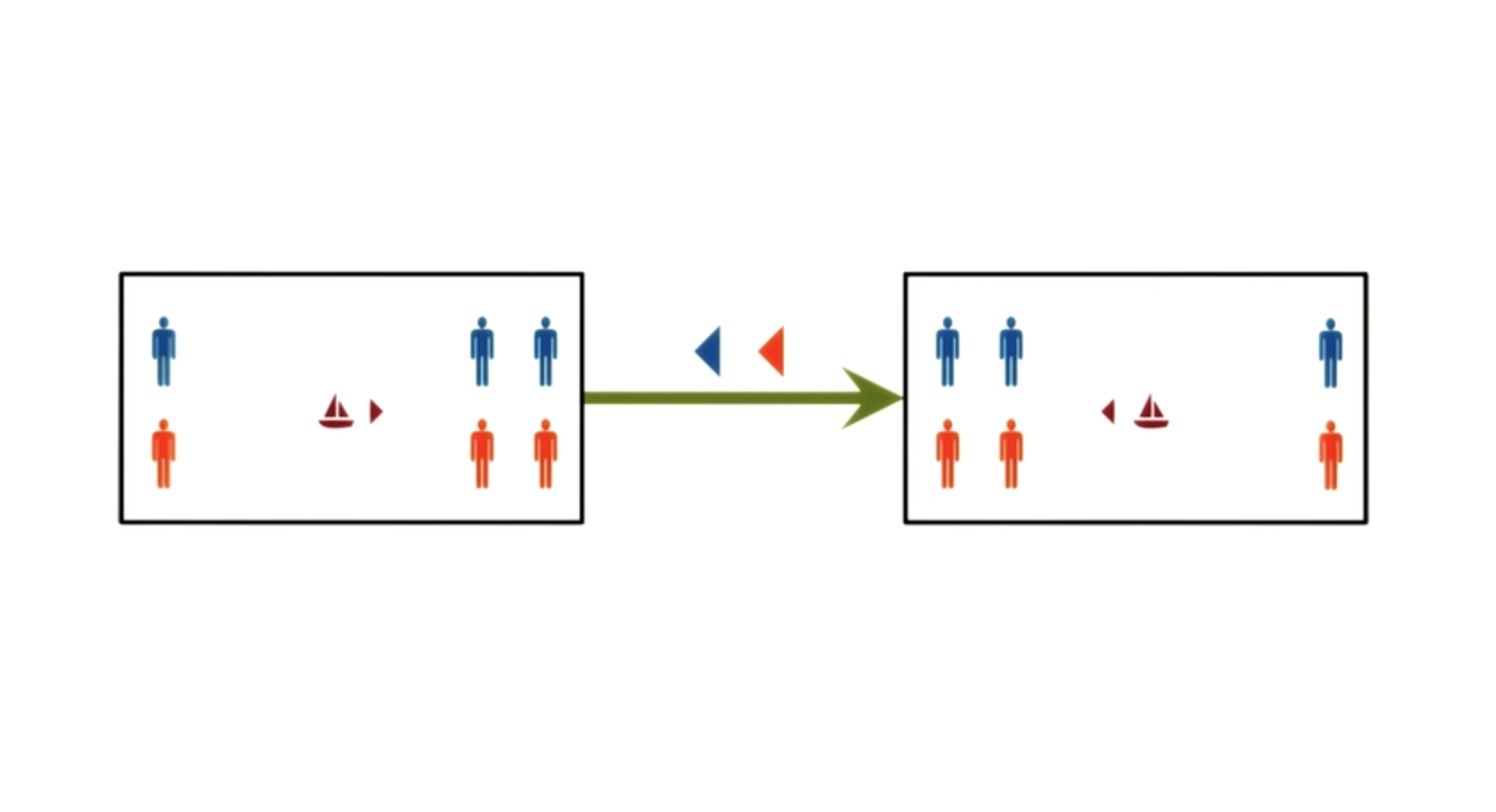

Let us try to construct a semantic network representation, for this guards and prisoners problem, and see how we can use it to, do the problem-solving. So in this representation, I’m going to say that each node is a state in the problem-solving. In this particular state, there happens to be one guard and one prisoner on the left side. The boat is on the right side, and two of the prisoners and two of the guards are also on the right side.

So this is a node, one single node. So the node captured, the lexicon of the semantic network. Now, we’ll add the structural part. And the structural part has to do with the transformation. That is going connect different nodes, into a more complex sentence. We’ll label the links between the nodes, and these labels then, will capture some of the semantics of this representation, which will allow us to make interesting inferences, when it comes time to do the problem-solving. Here is a second node, and this node represents a different state in the problem-solving. In this case, there are two guards and two prisoners on the left side.

The boat is also on the left side. There is one guard and one prisoner on the right side. So this now, is a, semantic network.

A node, another node, a link between them and the link is labeled.

Note that in this representation, I used icons to represent objects, as well as icons to represent labels of the links between the nodes.

This is perfectly valid. You don’t have to use words. You can use icons, as long as you’re capturing the nodes and the objects inside each state, as well as the labels on the links between the different nodes.

- state []

- guards G

- prisoner P

- boat B

- river |

[GGGPPPB|]-(GP)->[GGPP|BGP]

Solving the “Guards and Prisoners” Problem

There’s an old saying in AI, which goes like, if you have the right knowledge representation, problem-solving becomes very easy. Let’s see whether that also works here.

We now have a knowledge representation for this problem of guards and prisoners.

Does this knowledge representation immediately afford effective problem-solving?

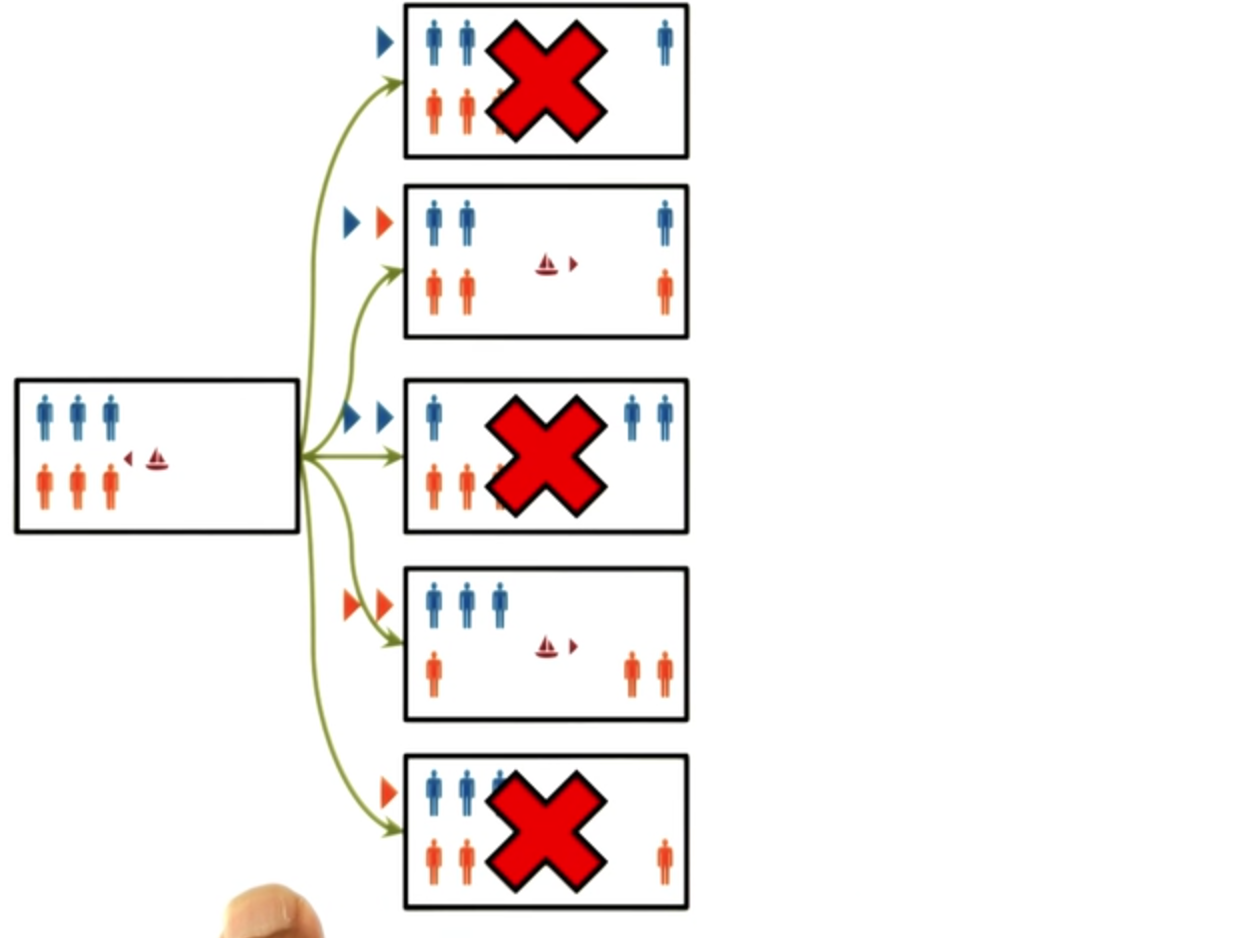

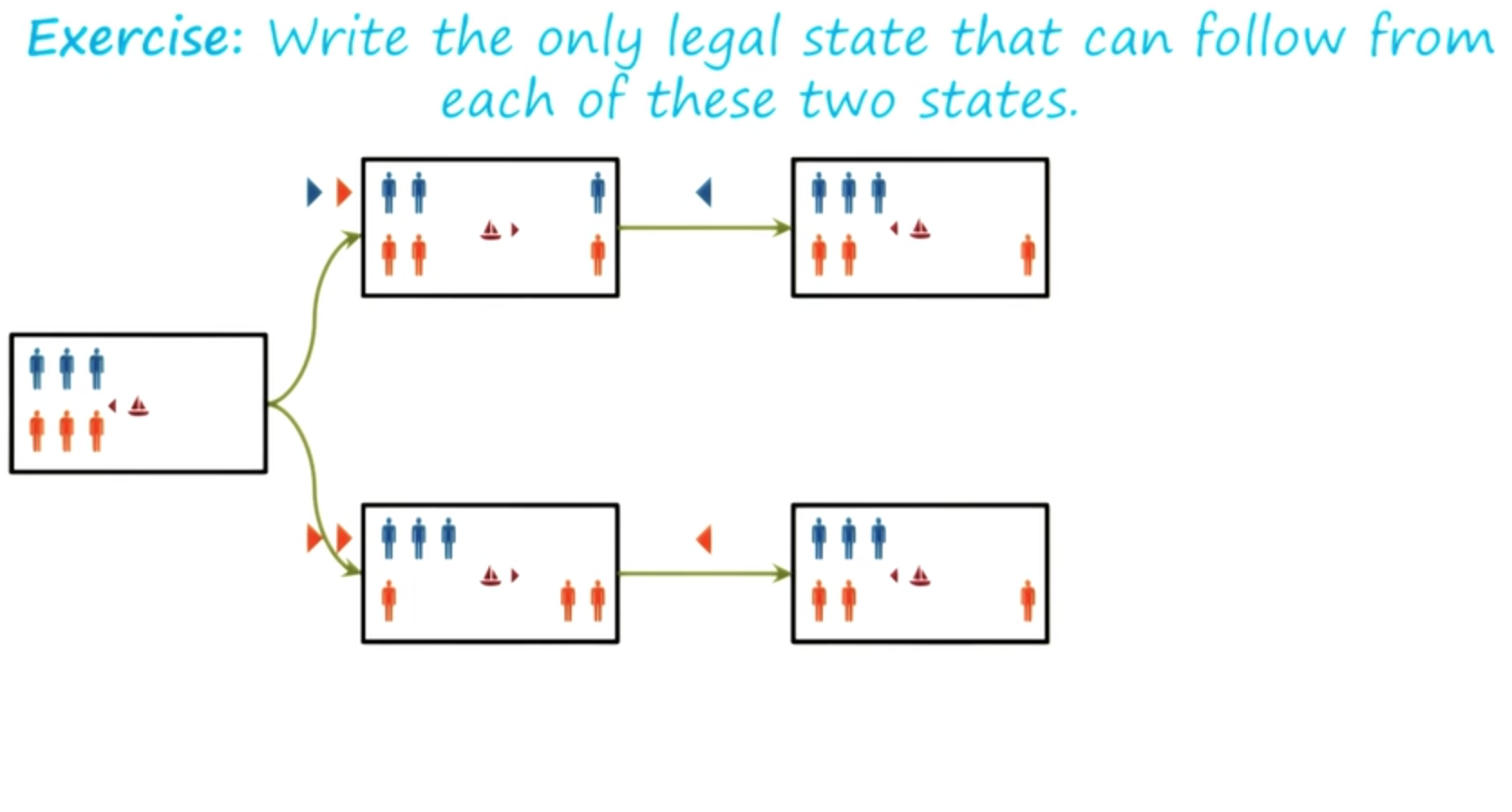

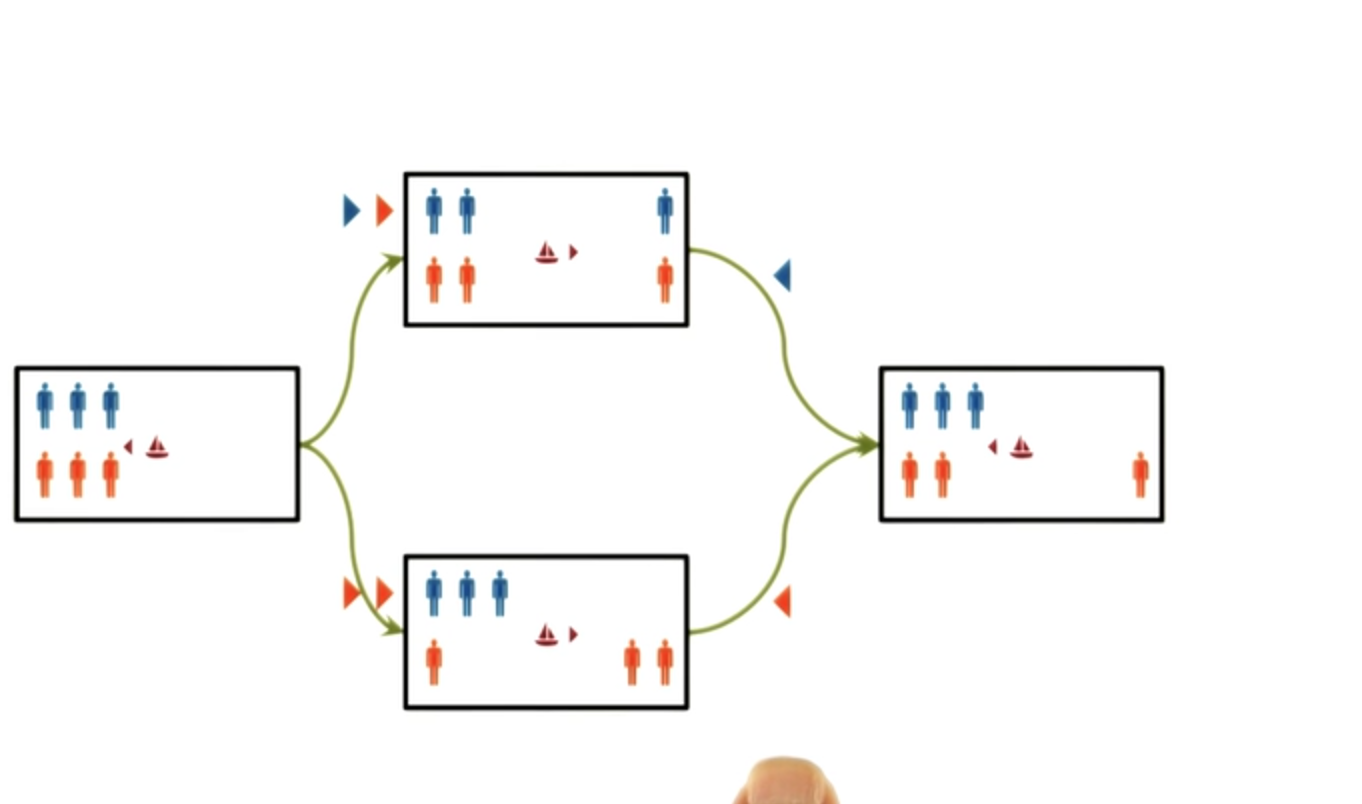

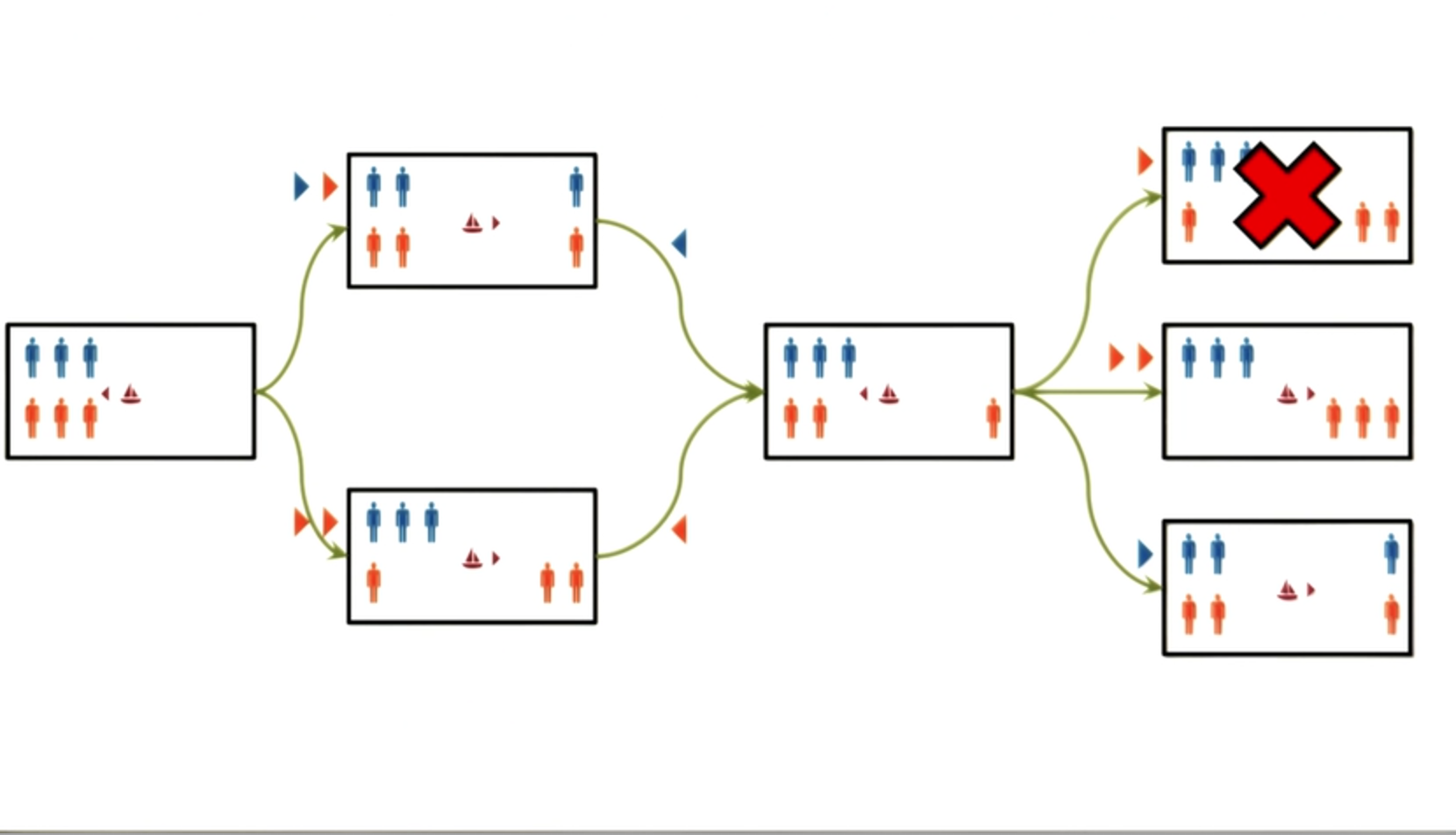

So, here we are in the first node, the first state. There are three guards and three prisoners in the boat, all in the left-hand side. Let us see what moves are possible from this initial state. Now, using this representation, we can quickly figure out that there are five possible moves from the initial state.

And the first move, we move only guard to the right. On the second move, we move a guard and a prisoner to the right. In the third move, we can move two guards, or two prisoners. Or, in the fifth move, just one prisoner to the right.

Five possible moves. Of course, we know that some of these moves are illegal and some of them are likely to be not very productive. Will the semantic network allow us to make inferences about which moves are productive and which moves are not productive? Let’s see further. So, let’s look at the legal moves first. So we can immediately make out from this representation, that the first move is not legal because we are not allowed to have more prisoners than guards on one side, of the river.

Similarly, we know that the third move is illegal for the same reason.

So, we can immediately rule out the first and the third moves. The fifth move, too, can be ruled out. Let’s see how. We have one prisoner on the other side.

But the only way to go back would be to take the prisoner to the, back to the previous side. And if we do that, we reach the initial state.

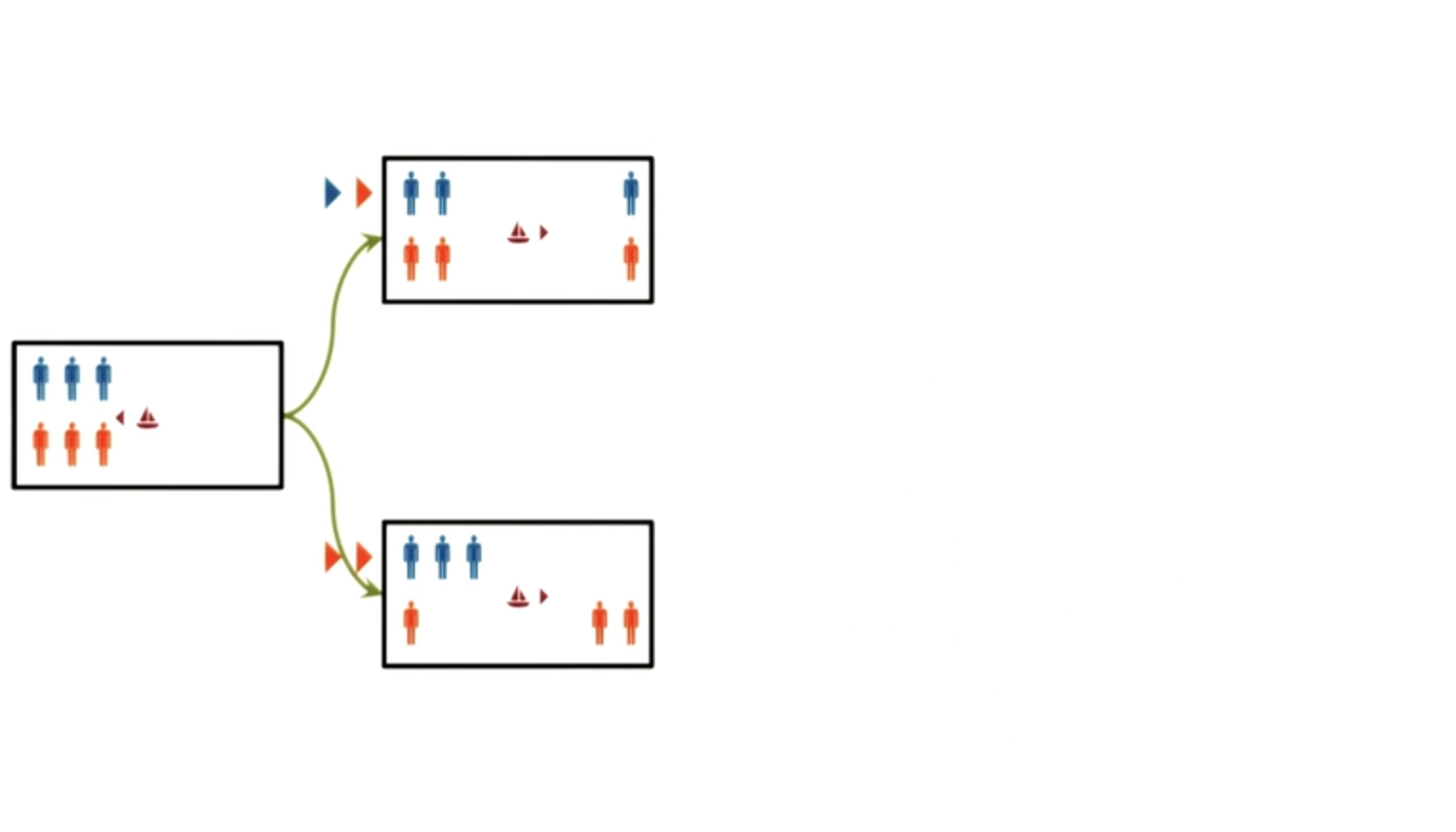

So we did not make any forward progress. Therefore, we can rule out this move as well. This leaves us with two possible moves that are both legal and productive. We have already removed the moves that were not legal and not productive. Later, we will see how AI programs can use various methods to figure out what moves are productive and what moves are unproductive.

For the time being, let’s go along with our problem-solving.

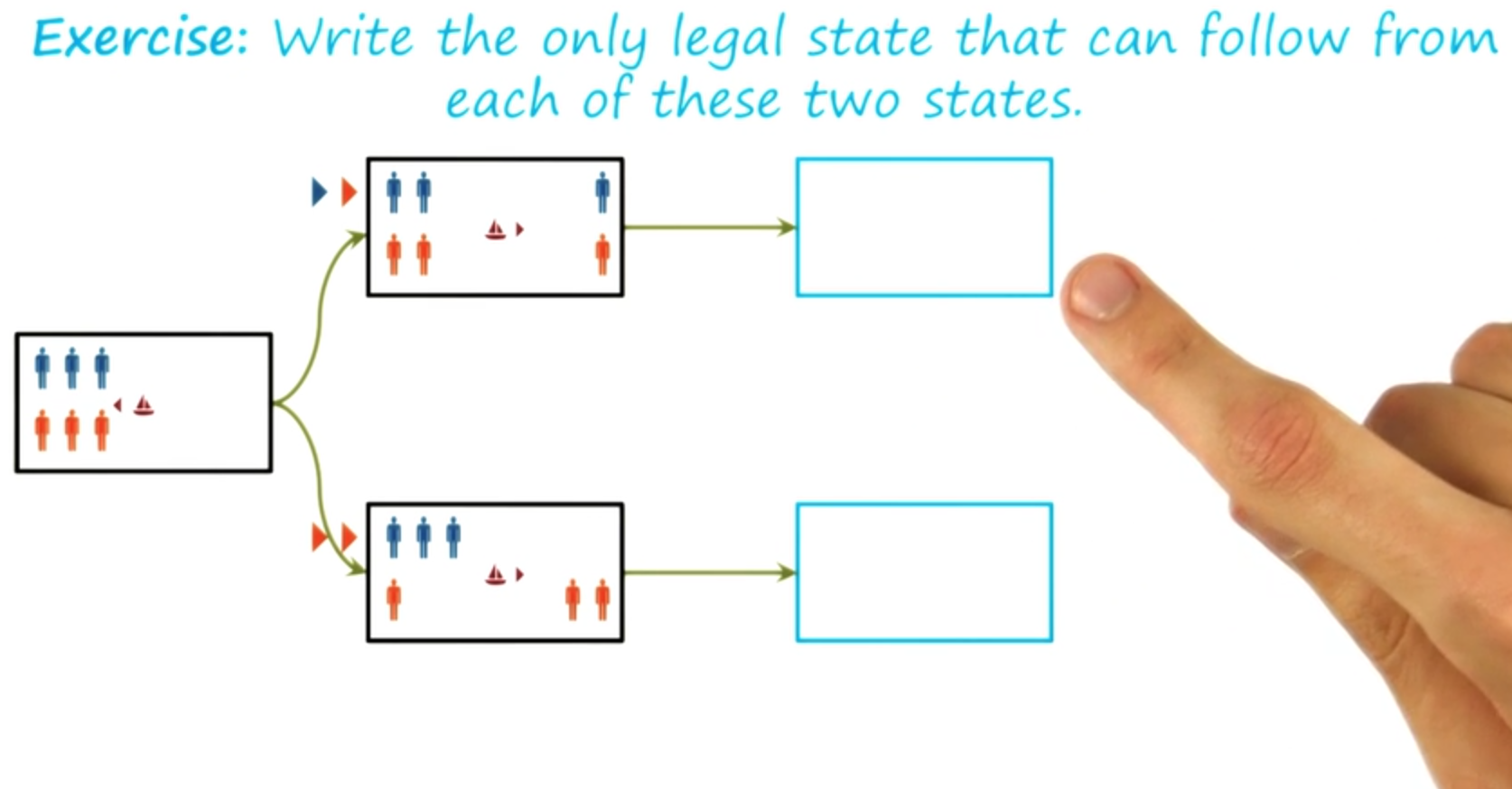

Exercise Guards and Prisoners I Quiz

Write the number of guards on the left coast in the top left box, just as a number zero, one, two, or three. The number of prisoners on the left coast in the bottom left box, the number of guards on the right coast in the top right box, and the number of prisoners on the right coast in the bottom right box.

Exercise Guards and Prisoners I - Answer

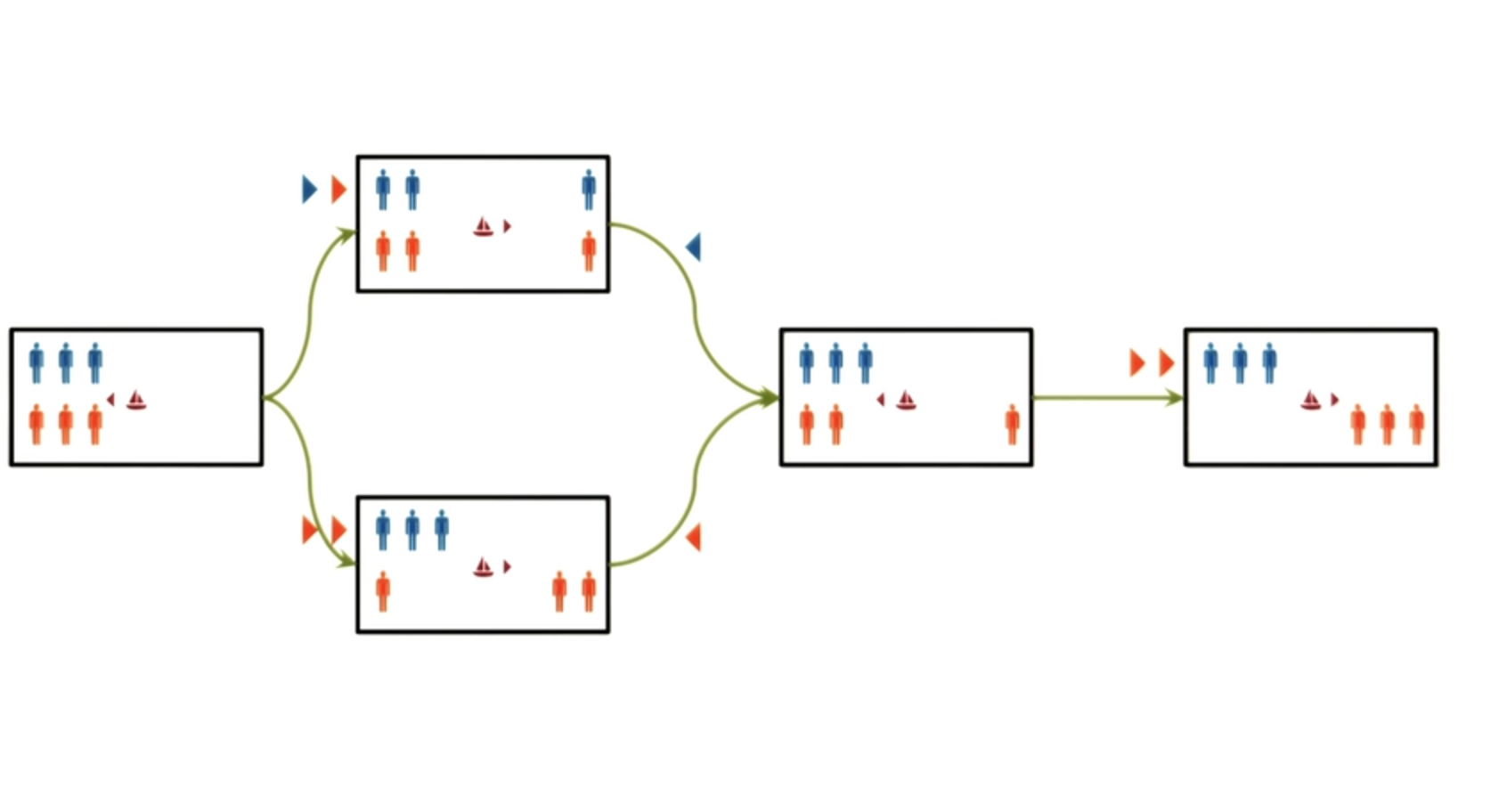

So, in this semantic network, we don’t really care how we got into a state, just as long as we know what state we are in. And that makes sense in this problem-solving process. Once we are in this state, we don’t care if we got to it this way or this way. All we care about is the current state of the problem.

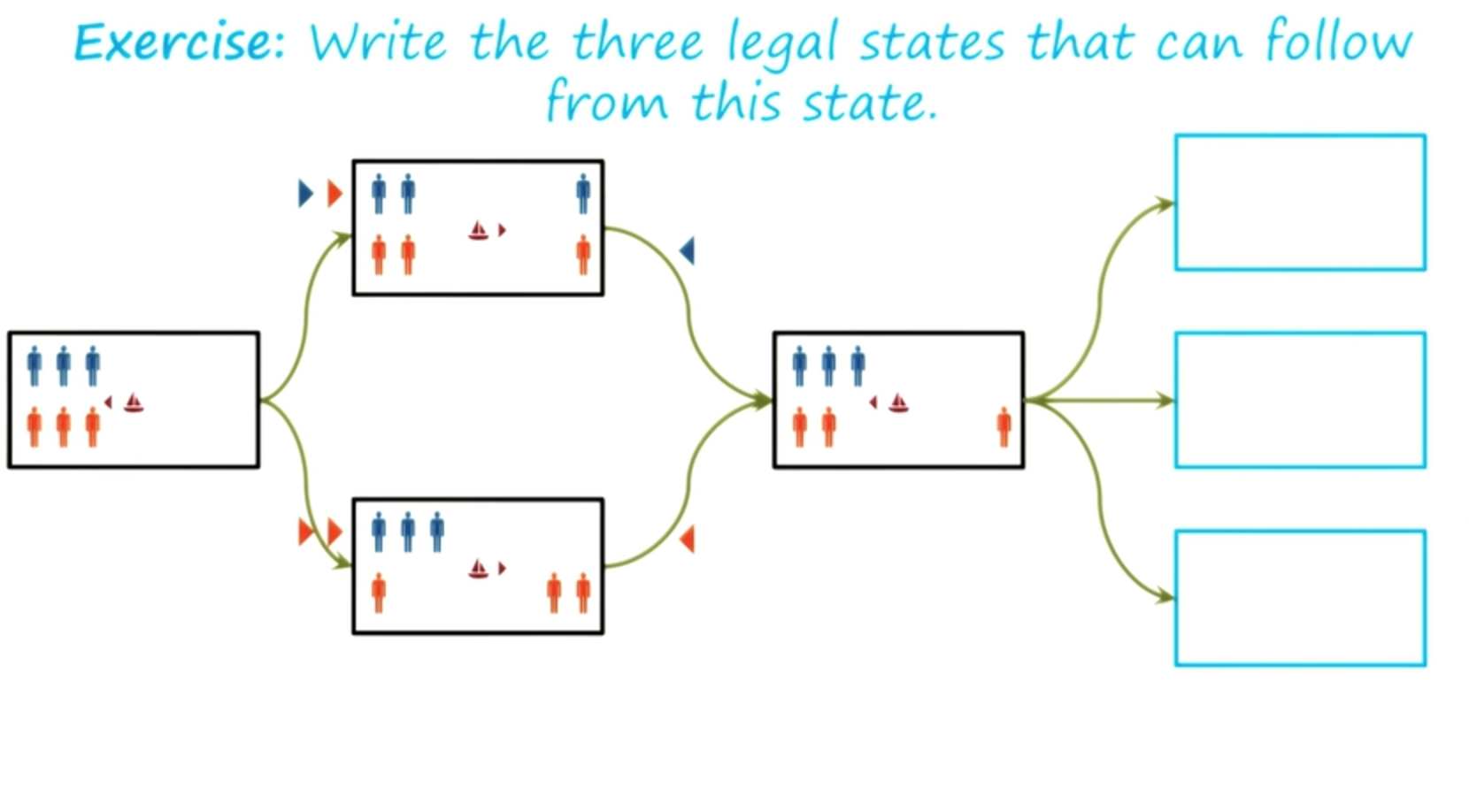

Exercise Guards and Prisoners II - Quiz

Let us take this problem-solving a little bit further. Now that we’re in this state, let us write down all the legal moves that can follow.

It will turn out that some of these legal moves will be unproductive, but first, let’s just write down the legal moves that can follow from here.

Exercise Guards and Prisoners II - Answer

So the power of this semantic network as a representation is arising because it allows us to systematically solve this problem because it makes all the constraints, all the objects, all the relationships, all the moves very explicit.

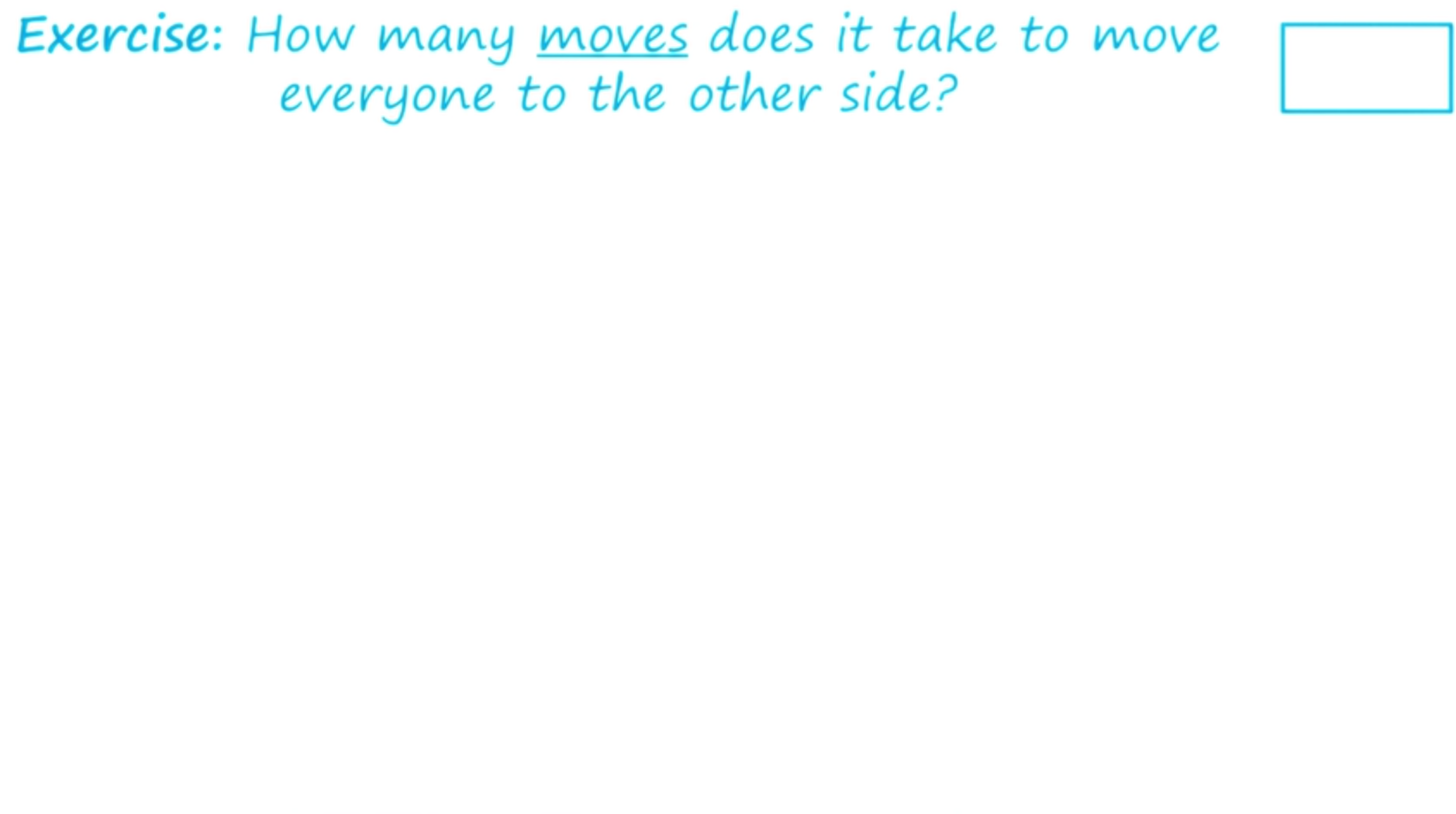

Exercise Guards and Prisoners III - Quiz

We can continue this problem-solving process further and solve this guards and prisoners problem. I’ll not do that here, both because it will take a long time, and because the entire picture will not fit into the screen. But

I would like you to do it yourself. And I want you to do it and tell me how many moves does it take to move all the guards and all the prisoners from one side to the other side of the river?

Once you are done. Once you have solved the problem and moved all the guards and prisoners to the other side, write the number of moves here in this box.

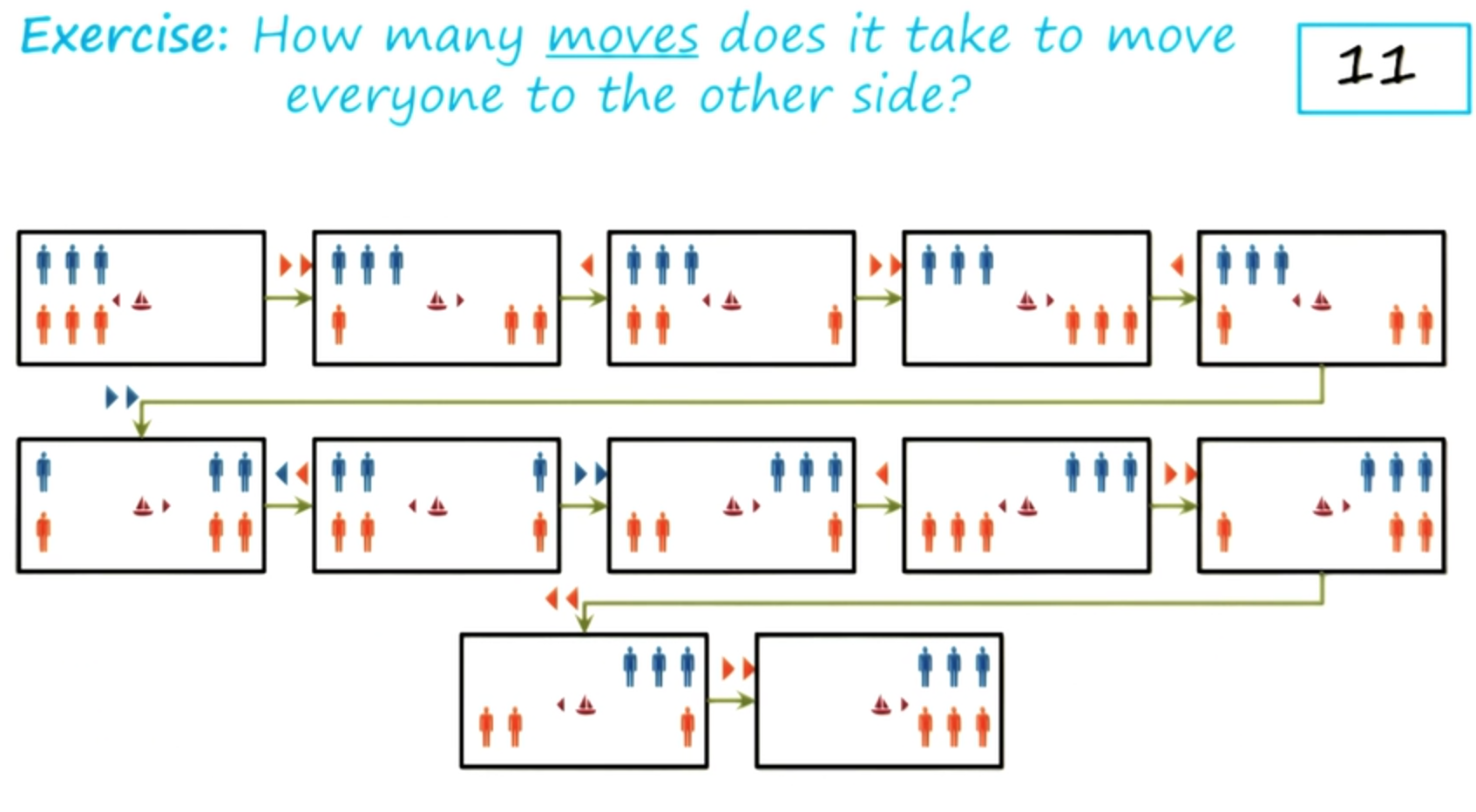

Exercise Guards and Prisoners III - Answer

So we’ve not yet talked about, how an AI method, can determine which states are productive and which states are unproductive.

We’ll revisit this issue in the next couple lessons.

Represent Reason for Analogy Problems

Now that we have seen how, the semantic network knowledge representation, enables problem-solving, let us return to that earlier problem that we were talking about. The problem of A is to B, as C is to 5.

Recall that we have worked out the representations for both A is to B and C is to 5. The question now becomes, whether we can use this representation, to decide whether or not 5 is the correct answer. If we look at the two representations in detail, then we see part of the representation here, is the same as the representation here. Except that, this part is different from this part. Here we have y expanded and right here, we have s remain unchanged.

So this may not be the best answer. Perhaps there is a better answer. Where the representation on the left, will exactly match representation on the right.

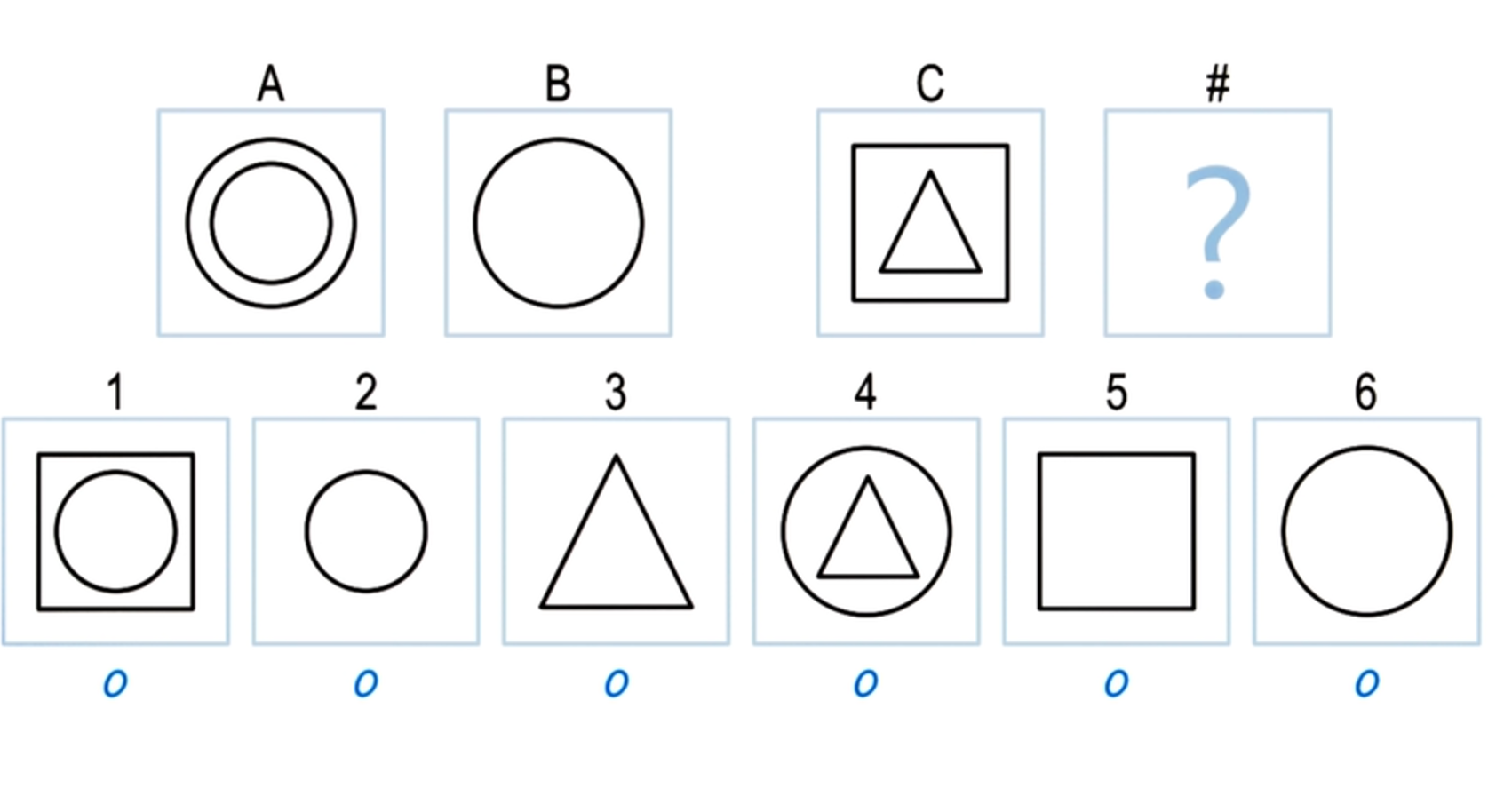

Exercise Represent Reason for Ravens - Quiz

So, let us do another exercise together. This time I have picked a different choice, choice 2 here. So now, we can build a representation for A is to B like earlier, and here is a representation of C is to 2.

I would like you to fill out these boxes for the labels on the links here.

And then answer whether or not two is the right answer for this problem.

Exercise Represent Reason for Ravens - Answer

That sounds fair. In fact, we’ll come across something like this very soon.

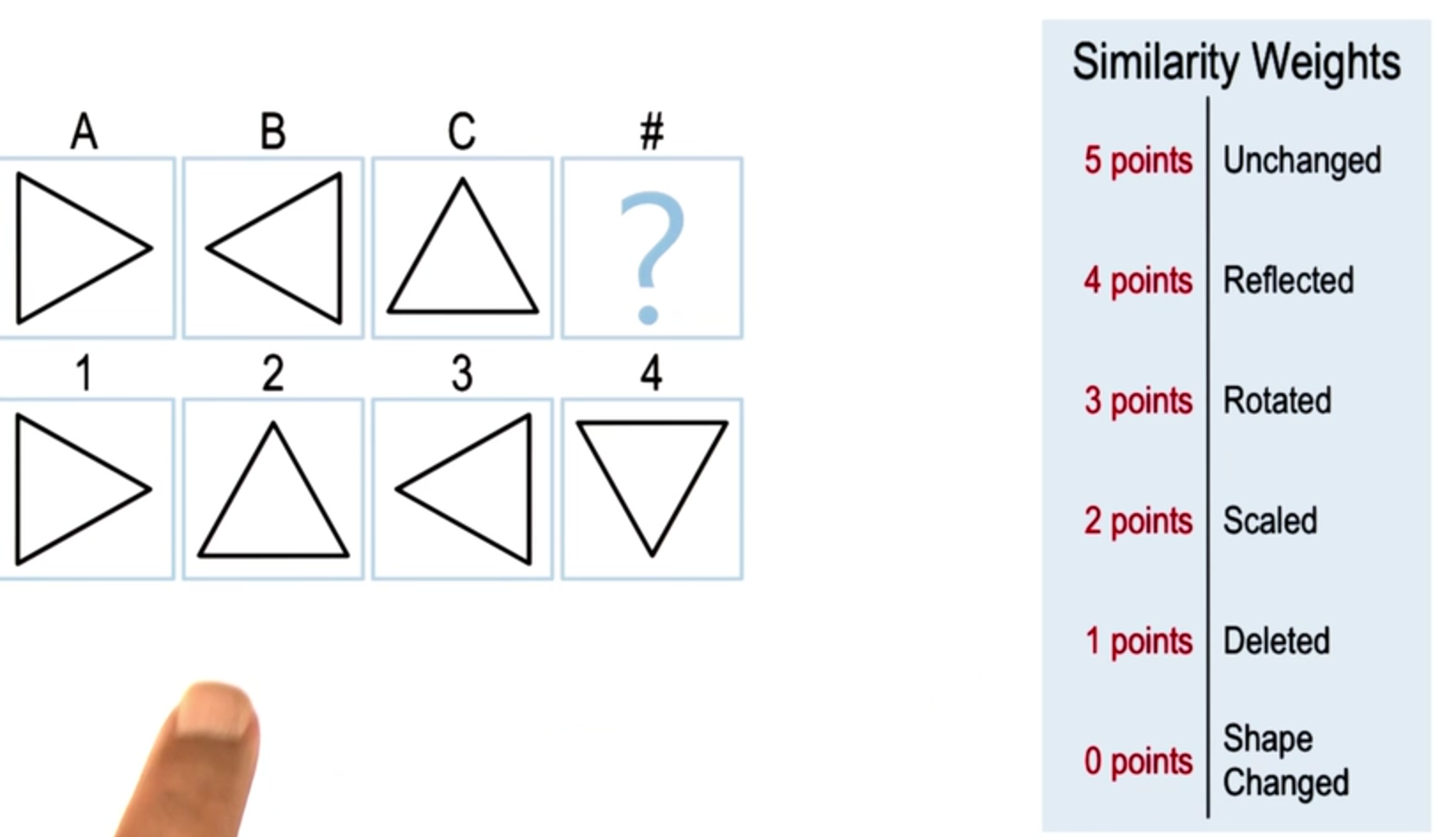

Exercise How do we choose a match

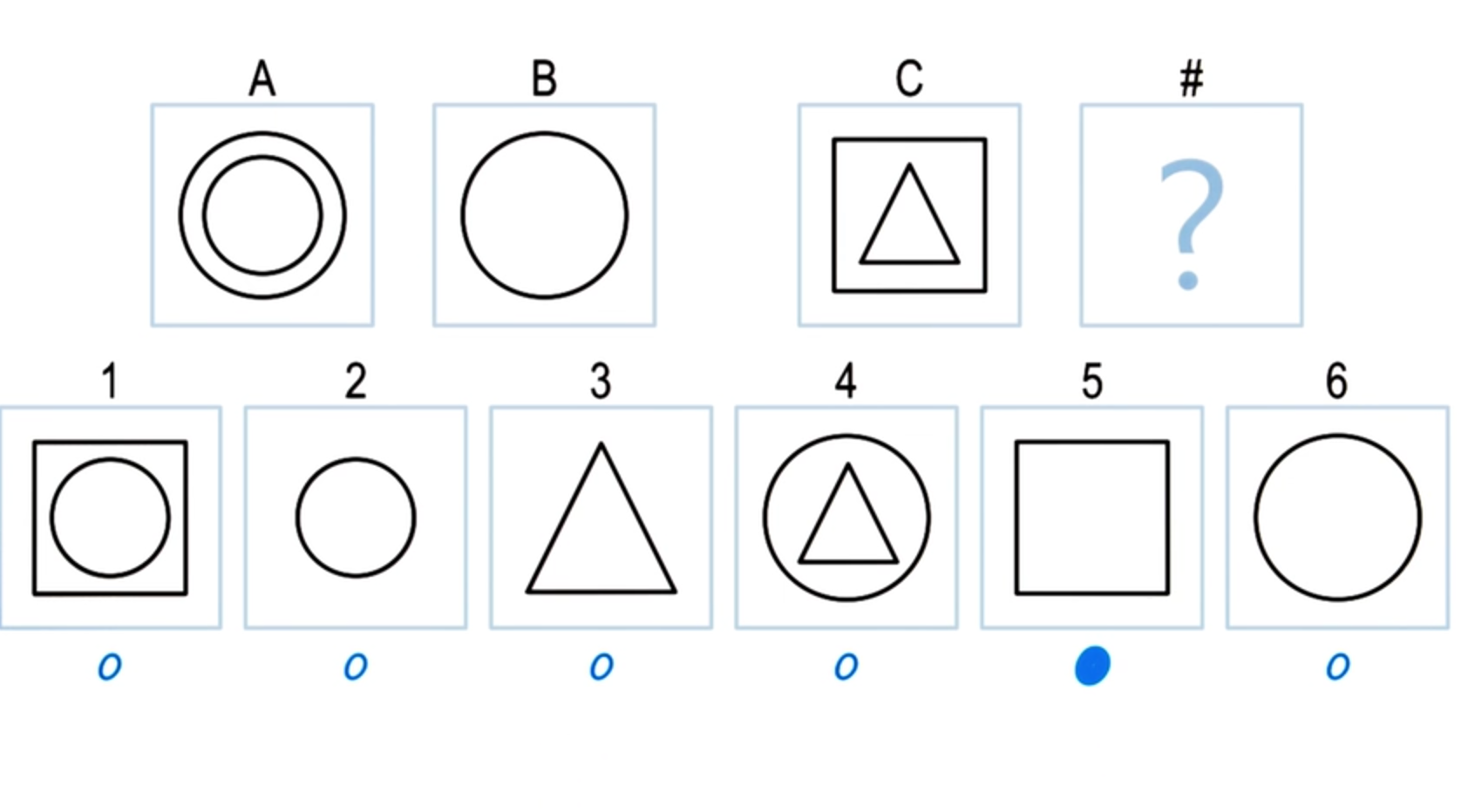

Let us do another exercise. This is actually an exercise we’ve come across earlier, however this exercise has an interesting property.

Often the world presents input to us, for which there is no one single right answer. Instead, there are multiple answers that could be right.

The world is ambiguous. So, here we again have A is to B, C is to D, and we have six choices. So, what choice do you think is the right choice here?

Exercise How do we choose a match

That’s a great question. Let’s look at this in more detail.

Choosing Matches by Weights

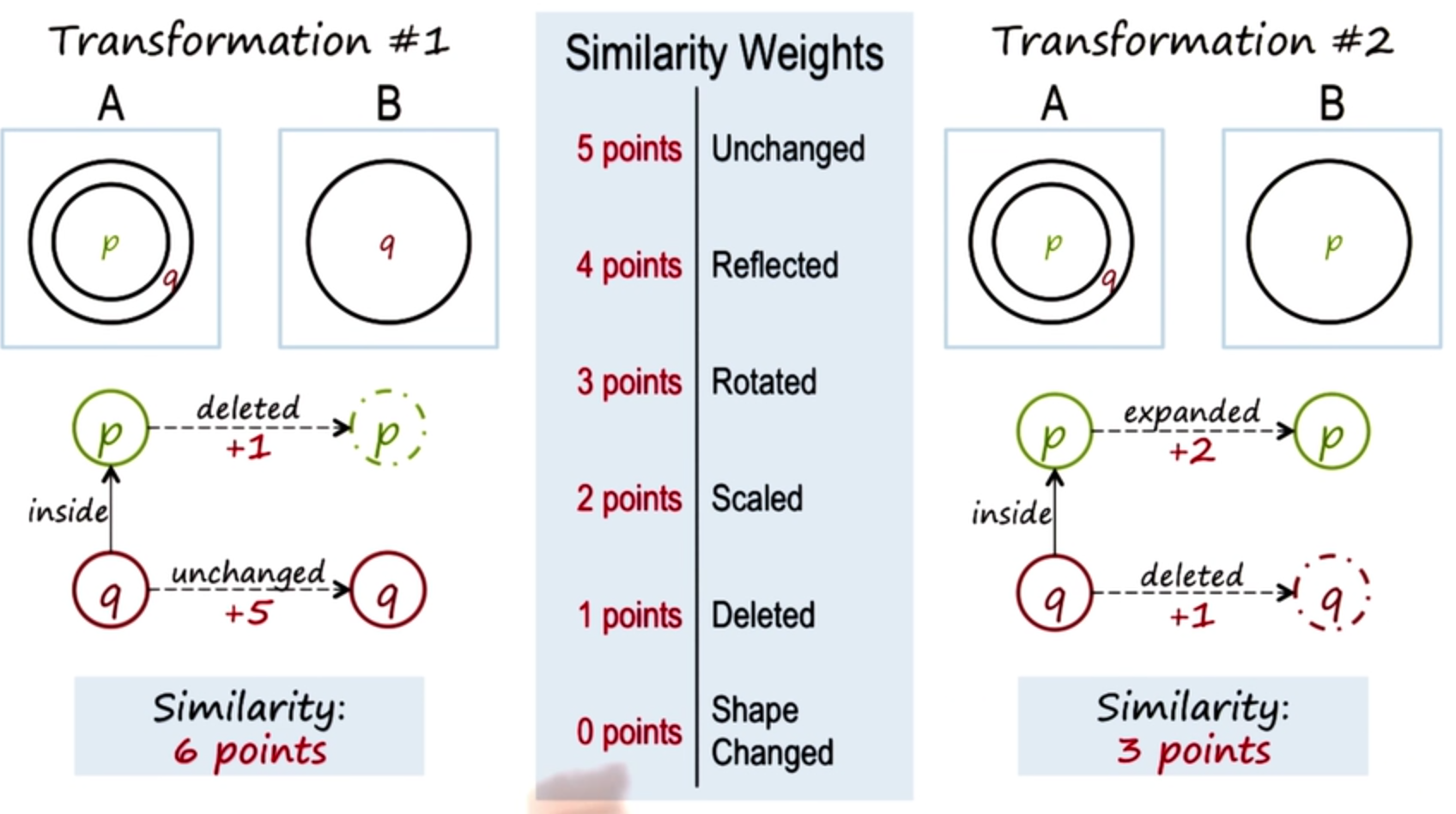

So let us look at the semantic network representation of the relationship between A and B. In one view of the transformation from A to B, we can think of q, the outer circle, as remaining unchanged, and p the inner circle, as getting deleted. Let’s look at another view of the transformation from A to B. In this view, we can think of p as getting expanded and q, the outer circle, as getting deleted.

Both of these views are valid views. If both of these views are valid, then how would anyone decide? How would an AI agent decide which view to select?

Let us suppose that the AI agent had a metric by which it could decide upon the ease of transformation from A to B.

Let us suppose that, that metric assigned different weights to different kind of transformations. You will notice that transformations like scaling, rotation, reflection make for a fine transformations. In this scale, a larger value like 5 points, means more ease of transformation and greater similarity. A lower value means less ease of transformation and more difficult transformation and less similarity. Given the scale, let us calculate the weight of transformations for both transformation #1, and transformation #2. In transformation #1, you can see that p is getting deleted, which we gave a weight of 1. And q remains unchanged, which we gave a weight of 5. So the total weight here is 6.

In case of transformation #2, the weight of p being expanded, we said will be 2, scaled. And, q getting deleted is 1, so the total weight is 3.

If you prefer the first transformation over the second transformation, then we can see why someone will answer the square is the correct answer, and not the triangle. Let us return to this exercise. And now we can see why both 3 and 5 are legitimate answers. We can also see why an AI agent may prefer 5, given the similarity metric that we talked about in the last shot.

Discussion Choosing a Match by Weight - Quiz

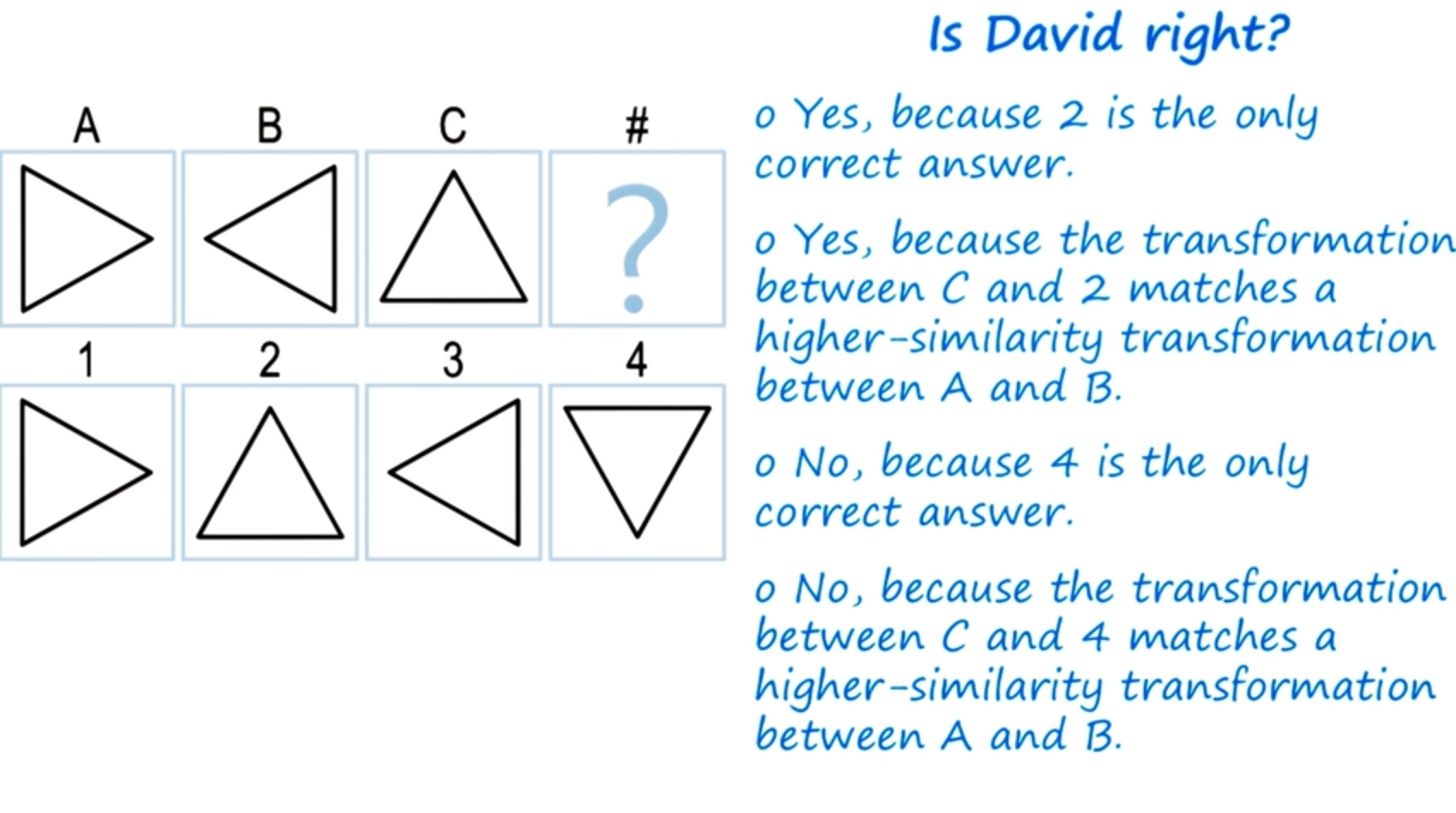

What does everyone think about David’s answer?

Did David give the right answer with two?

Discussion Choosing a Match by Weight - Answer

What is everyone think? Is 2 the right answer here? Well, lets look at the choices. First note, that both 2 and 4 are legitimate answers.

2 is legitimate because we can think of the transformation from

A to B as a reflection around the vertical axis. And so if we think of the transformation from C to D, again as a reflection of the vertical axis, we’ll get 2. 4 is also a correct answer, because we can think of the transformation from A to B as a rotation of 180 degrees, and if we rotate C by 180 degrees we’ll get 4. However, if we look at our weights again, we gave reflection a higher weight than we gave rotation. And therefore, David is right, 2 indeed is the correct answer.

Connections

Before we end this lesson, I want to draw several connections.

The first has to do with memory. We have often said that memory is an integral part of the cognitive systems architecture. One can imagine that A and B are stood in a memory. Then C and 1, and C and 2, and C and 3, and so on, are probes into the memory. And the question would then become, which one of these probes is most similar to what’s stored in memory? We may decide on that answer based on some similarity metric.

We’ll revisit this exactly the same issue when we talk about case-based reasoning later on in this class. Another connection we can draw here has to do with reasoning. When we are talking about the transformation from A to B and then the transformation to from C to 1 of these choices, one question that arose was should we make the connection between the outer circle here and B?

Or the inner circle and A and B. This is a correspondence problem. The correspondence problem is: given two situations, what object in one situation corresponds to what object in another situation? We will come across this problem again when we discuss analogical reason a little bit later.

The third connection has to do with cognition, of knowledge based AI as a whole. Notice that instead of just talking about properties of objects, like this is a circle and the size of the circle, our emphasis here has been on the relationships between the objects. The fact that this is inside the outer circle, or the fact that the outer circle remains the same here, the inner circle disappears. In knowledge-based AI and in cognition in general, the focus is always on relationships, not just on objects and the features of those objects.

Assignment Semantic Nets

The first assignment you can chose to do for this course is to talk about how these semantic networks can be used to represent Raven’s Progressive Matrices.

We saw a few different problems in the first lesson. So take a look at how the semantic networks we’ve talked about today can be used to represent some of those other problems, and write your own kind of representation scheme.

In addition to writing a representation scheme, also talk about how that representation scheme actually enables problem-solving. Remember what Ashok mentioned about the different qualities of a good knowledge representation that is complete. It captures information at the right level of abstraction, and it enables problem-solving. So write how your representation can enable problem-solving of two by one, two by two, and three-by-three problems. You don’t need to use the exact same representation scheme that we use, and in fact you can and should use your own. Also remember that your representation should not capture any details about what the actual answer to the problem is, but rather it should only capture what’s actually in the figures in the particular problem.

Wrap Up

So let’s recap what we’ve talked about today. We started off today by talking about one of the most important concepts in all of knowledge based AI, which are knowledge based representations. As we go forward in this class, we’ll see knowledge representations are really at the heart of nearly everything we’ll do. We then talked about semantic networks, which are a good particular kind of representation and we used those to talk about the different criteria for a good knowledge representation. What do good knowledge representations enable us to do and what to they help us avoid? We then talked about kind of an abstract class of problem-solving methods called Represent and Reason. Represent and reason really lies under all of knowledge based AI and it’s a way of representing knowledge and then reasoning over it.

We then talked a little bit about augmenting that with weight, which allows us to come to more nuanced and specific conclusions. In the next couple weeks, we are going to use these semantic networks to talk about a few different problem-solving methods. Next time, we’ll talk about generate and test and then we’ll move on to a couple slightly different ones called Means and Ends Analysis and Problem Reduction.

The Cognitive Connection

How is semantic networks connected with human cognition?

Well we can make at least two connections immediately. First, semantic networks are kind of knowledge representation. We saw hive knowledge is presented as a semantic network. If the results of representation, then you can use the knowledge presentation to address the problem.

We can now say similarly for human mind that human mind represents problems.

It represents knowledge. Then it uses that knowledge to address the problem.

So, representation then becomes the key. Second, and most specifically, semantic networks are related to spreading activation networks, which is a very popular theory of human memory. Let me give you an example.

Supposing I told you a story consisting of just two sentences. John wanted to become rich. He got a gun. And notice that I did not tell you the entire story, but I’m sure you all made up a story based on what I told you.

John wanted to become rich. He decided to rob a bank.

He got a gun in order to rob the bank. But how did you end this story?

How did it draw the inferences about robbing a bank which I did not tell you anything about? Imagine if you have a semantic network that consisted of a large number of nodes. So when I gave you the first sentence, John wanted to become rich, the nodes corresponding to John and wanted and become and rich, got activated, and the activation started spreading from those nodes.

And when I said John, he got a gun, then the gun node also got activated and that activation also started spreading. As this activation spread, it merged. And a path they could walk on. And all the nodes on that pathway now become part of the story, and if you happen to have nodes like, rob a bank along the pathway, now you have understanding of story.

References

Footnotes

How should we name the states and their constituent entities? How should we identify entities between states?↩︎

There are can be multiple competing alternatives for the transformation. We need to be able to encode these different transformations in our representation.↩︎

for a general AI one would expect being able to solve new problems with transformation that have not been seen in training AKA

zero-shot learning↩︎We may have encoded a transformation that generates a solution that satisfies the analogy step but is not part of the solution. ↩︎

Human rankings, AI rankings and possibly task specific rankings.↩︎

by using the right level of abstraction↩︎

captures only what is needed↩︎

it doesn’t have all the details that are not needed↩︎

it allows you to draw from the inferences that need to be drawn↩︎

Reuse

Citation

@online{bochman2016,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {Lesson 03 {Semantic} {Networks}},

date = {2016-01-25},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/notes/cognitivie-ai-cs7637/03-semantic-networks/03-semantic-networks.html},

langid = {en}

}