Definition and state-space representation (video)

AR(P) is shorthand for autoregressive process of order p which generalizes the AR(1) process that we studied in the previous module. It is essentially a mapping that allows us to specify the current value of the time series in terms its past p-values and some noise. The number of parameter p, required is the order of the autoregressive process. It tells us how many lags we will be considering.

order

We will assume AR(P) has the following structure:

\textcolor{red}{y_t} = \textcolor{blue}{\phi_1} \textcolor{red}{y_{t-1}} + \textcolor{blue}{\phi_2} \textcolor{red}{y_{t-2}} + \ldots + \textcolor{blue}{\phi_p} \textcolor{red}{y_{t-p}} + \textcolor{grey}{\epsilon_t} \qquad

\tag{1}

where:

\textcolor{red}{y_t} is the value of the time series at time t

\textcolor{blue}{\phi_{1:p}} are the AR coefficients

\textcolor{grey}{\epsilon_t} \overset{\text{iid}}{\sim} \text{N}(0,v) \quad \forall t is a white noise process.

The number of parameters has increased from one coefficient in AR(1) to p coefficients for AR(P).

A central outcome of the autoregressive nature of the AR(p) is due to the properties the AR characteristic polynomial \Phi. This is defined as :

\Phi AR characteristic polynomial

recall the backshift operator B is defined as B y_t = y_{t-1}, so that B^j y_t = y_{t-j}.

\begin{aligned}

y_t &= \phi_1 y_{t-1} + \phi_2 y_{t-2} + \ldots + \phi_p y_{t-p} + \epsilon_t && \text{(Ar(p) defn.)} \newline

y_t &= \phi_1 By_{t} + \phi_2 B^2y_{t} + \ldots + \phi_p B^p y_{t} + \epsilon_t && \text{(B defn.)} \newline

\epsilon_t &= y_t - \phi_1 B y_t + \phi_2 B^2 y_t + \ldots + \phi_p B^p y_t && \text{(rearranging)} \newline

\epsilon_t &= (1- \phi_1 B + \phi_2 B^2 + \ldots + \phi_p B^p) y_t && \text{(factoring out $y_t$)}

\end{aligned}

\Phi(z) = 1 - \phi_1 z - \phi_2 z^2 - \ldots - \phi_p z^p \qquad \text{(Characteristic polynomial)}

\tag{2}

where:

- z \in \mathbb{C} i.e. complex-valued.

we can also rewrite the characteristic polynomial in terms of the reciprocal roots of the polynomial.

The zeros of the characteristic polynomial are the roots of the AR(p) process.

\Phi(z) = \prod_{j=1}^{p} (1 - \alpha_j z) = 0 \implies z = \frac{1}{ \alpha_j} \qquad \text{(reciprocal roots)}

where:

- \alpha_j are the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial.

Why are we interested in this autoregresive lag polynomial?

- This polynomial and its roots informs us a lot about the process and its properties.

- One of the main characteristics is it allows us to think about things like quasi-periodic behavior, whether it’s present or not in a particular AR(p) process.

- It allows us to think about whether a process is stationary or not, depending on some properties related to this polynomial.

- In particular, we are going to say that the process is stable if all the roots of the characteristic polynomial have a modulus greater than one.

\Phi(z) = 0 \iff |z| > 1 \qquad \text{(stability condition)}

\tag{3}

- For any of the roots, it has to be the case that the modulus of that root, they have to be all outside the unit circle.

- If a process is stable, it will also be stationary.

stability condition

We can show this as follows:

- Once the process is stationary, and if all the roots of the characteristic polynomial are outside the unit circle, then we will be able to write this process in terms of an infinite order moving average process. In this case, if the process is stable, then we are going to be able to write it like this.

y_t = \Psi(B) \epsilon_t = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \psi_j \epsilon_{t-j} \ \text {with} \ \psi_0 = 1 \text{ and } \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |\psi_j| < \infty

\tag{4}

where:

- \epsilon_t is a white noise process with zero mean and constant variance v.

- B is the lag operator AKA the backshift operator defined by B \varepsilon_t = \varepsilon_{t-1}. This need to be applied to a time series \epsilon_t to get the lagged values.

- \Psi(B) is the infinite order polynomial in B that representing a linear filter applied to the noise process.

- \psi_t = 1 is the weight for the white noise at time t.

- the constraint \psi_0 = 1 ensures that the current shock contributes directly to y_t

- the constraint on the weights \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |\psi_j| < \infty ensures that the weights decay sufficiently fast, so that the process does not explode i.e. it is stable and thus stationary.

the notation with \psi a functional of operator B and \psi_i as constants is confusing in both the reuse if the symbol and the complexity.

Here, U is any complex valued number.

I am going to have an infinite order polynomial here on B, the backshift operator that I can write down just as the sum, j goes from zero to infinity.

Here \psi_0=1. Then there is another condition on the Psi’s for this to happen. We have to have finite sum of these on these coefficients. Once again, if the process is stable, then it would be stationary and we will be able to write down the AR as an infinite order moving average process here. If you recall, B is the backshift operator. Again, if I apply this to y_t, I’m just going to get y_t-j. I can write down Psi of B, as 1 + \psi_1 B, B squared, and so on. It’s an infinite order process.

The AR characteristic polynomial can also be written in terms of the reciprocal roots of the polynomial. So instead of considering the roots, we can consider the reciprocal roots. In that case, let’s say the $phi$ of u for Alpha 1, Alpha 2, and so on. The reciprocal roots. Why do we care about all these roots? Why do we care about this structure? Again, we will be able to understand some properties of the process based on these roots as we will see.

We will now discuss another important representation of the AR(P) process, one that is based on a state-space representation of the process. Again, we care about this type of representations because they allow us to study some important properties of the process. In this case, our state-space or dynamic linear model representation, we will make some connections with these representations later when we talk about dynamic linear models, is given as follows for an AR(P). I have my y_t. I can write it as F transpose and then another vector x_t here. Then we’re going to have x_t is going to be a function of x_t minus 1. That vector there is going to be an F and a G. I will describe what those are in a second. Then I’m going to have another vector here with some distribution. In our case, we are going to have a normal distribution also for that one. In the case of the AR(P), we’re going to have x_t to be y_t, y_t minus 1. >It’s a vector that has all these values of the y_t process. Then F is going to be a vector. It has to match the dimension of this vector. The first entry is going to be a one, and then I’m going to have zeros everywhere else. The w here is going to be a vector as well. > >The first component is going to be the Epsilon t. That we defined for the ARP process. Then every other entry is going to be a zero here. Again, the dimensions are going to match so that I get the right equations here. Then finally, my G matrix in this representation is going to be a very important matrix, the first row is going to contain the AR parameters, the AR coefficients. >We have p of those. That’s my first row. In this block, I’m going to have an identity matrix. It’s going to have ones in the diagonal and zeros everywhere else. I’m going to have a one here, and then I want to have zeros everywhere else. In this portion, I’m going to have column vector here of zeros. This is my G matrix. Why is this G matrix important? This G matrix is going to be related to the characteristic polynomial, in particular, is going to be related to the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial that we discussed before. The eigenvalues of this matrix correspond precisely to the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial. We will think about that and write down another representation related to this process. But before we go there, I just want you to look at this equation and see that if you do the matrix operations that are described these two equations, you get back the form of your autoregressive process. The other thing is, again, this is called a state-space representation because you have two equations here. One, you can call it the observational level equation where you are relating your observed y’s with some other model information here. Then there is another equation that has a Markovian structure here, where x_t is a function of x_t minus 1. This is why this is a state-space representation. One of the nice things about working with this representation is we can use some definitions that apply to dynamic linear models or state-space models, and one of those definitions is the so-called forecast function. The forecast function, we can define it in terms of, I’m going to use here the notation f_t h to denote that is a function f that depends on the time t that you’re considering, and then you’re looking at forecasting h steps ahead in your time series. If you have observations up to today and you want to look at what is the forecast function five days later, you will have h equals 5 there. It’s just the expected value. We are going to think of this as the expected value of y_t plus h. Conditional on all the observations or all the information you have received up to time t. I’m going to write it just like this. Using the state-space representation, you can see that if I use the first equation and I think about the expected value of y_t plus h is going to be F transpose, and then I have the expected value of the vector x_t plus h in that case. I can think of just applying this, then I would have expected value of x_t plus h given y_1 up to t. But now when I look at the structure of x_t plus h, if I go to my second equation here, I can see that x_t plus h is going to be dependent on x_t plus h minus 1, and there is a G matrix here. I can write this in terms of the expected value of x_t plus h, which is just G, expected value of x_t plus h minus 1, and then I also have plus expected value of the w_t’s. But because of the structure of the AR process that we defined, we said that all the Epsilon T’s are independent normally distributed random variables center at zero. In this case, those are going to be all zero. I can write down this as F transpose G, and then I have the expected value of x_t plus h minus 1 given y_1 up to t. If I continue with this process all the way until I get to time t, I’m going to get a product of all these G matrices here, and because we are starting with this lag h, I’m going to have the product of that G matrix h times. I can write this down as F transpose G to the power of h, and then I’m going to have the expected value of, finally, I get up to here. > >This is simply is going to be just my x_t vector. I can write this down as F transpose G^h, and then I have just my x_t. Again, why do we care? Now we are going to make that connection with this matrix and the eigenstructure of this matrix. I said before, one of the features of this matrix is that the eigenstructure is related to the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial. In particular, the eigenvalues of this matrix correspond to the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial. If we are working with the case in which we have exactly p different roots. We have as many different roots as the order of the AR process. Let’s say, p distinct. >We can write down then G in terms of its eigendecomposition. I can write this down as E, a matrix Lambda here, E inverse. > >Here, Lambda is going to be a diagonal matrix, >you just put the reciprocal roots, I’m going to call those Alpha 1 up to Alpha p. They are all different. You just put them in the diagonal and you can use any order you want. But the eigendecomposition, the eigenvectors, have to follow the order that you choose for the eigenvalues. Then what happens is, regardless of that, you’re going to have a unique G. But here, the E is a matrix of eigenvectors.

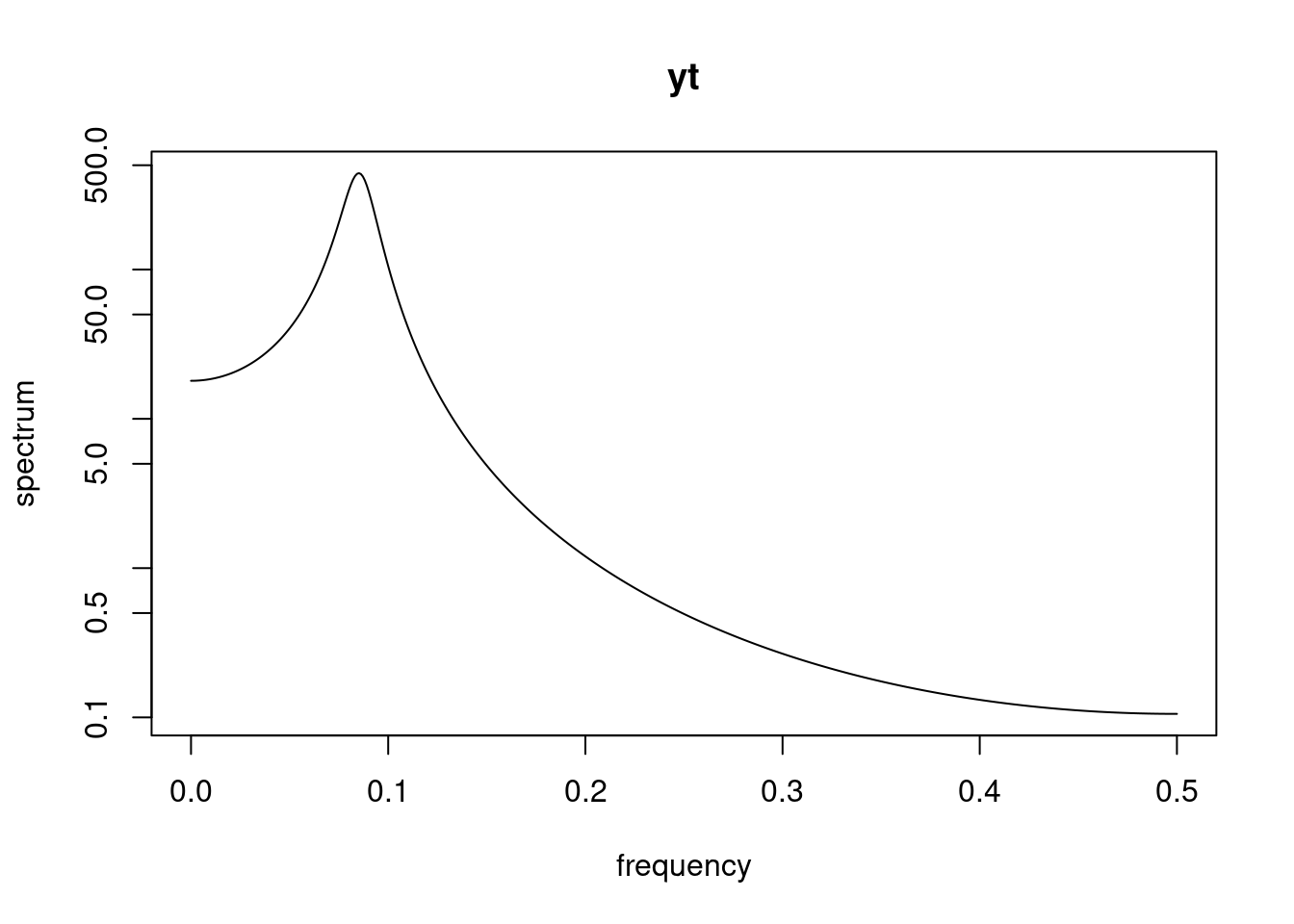

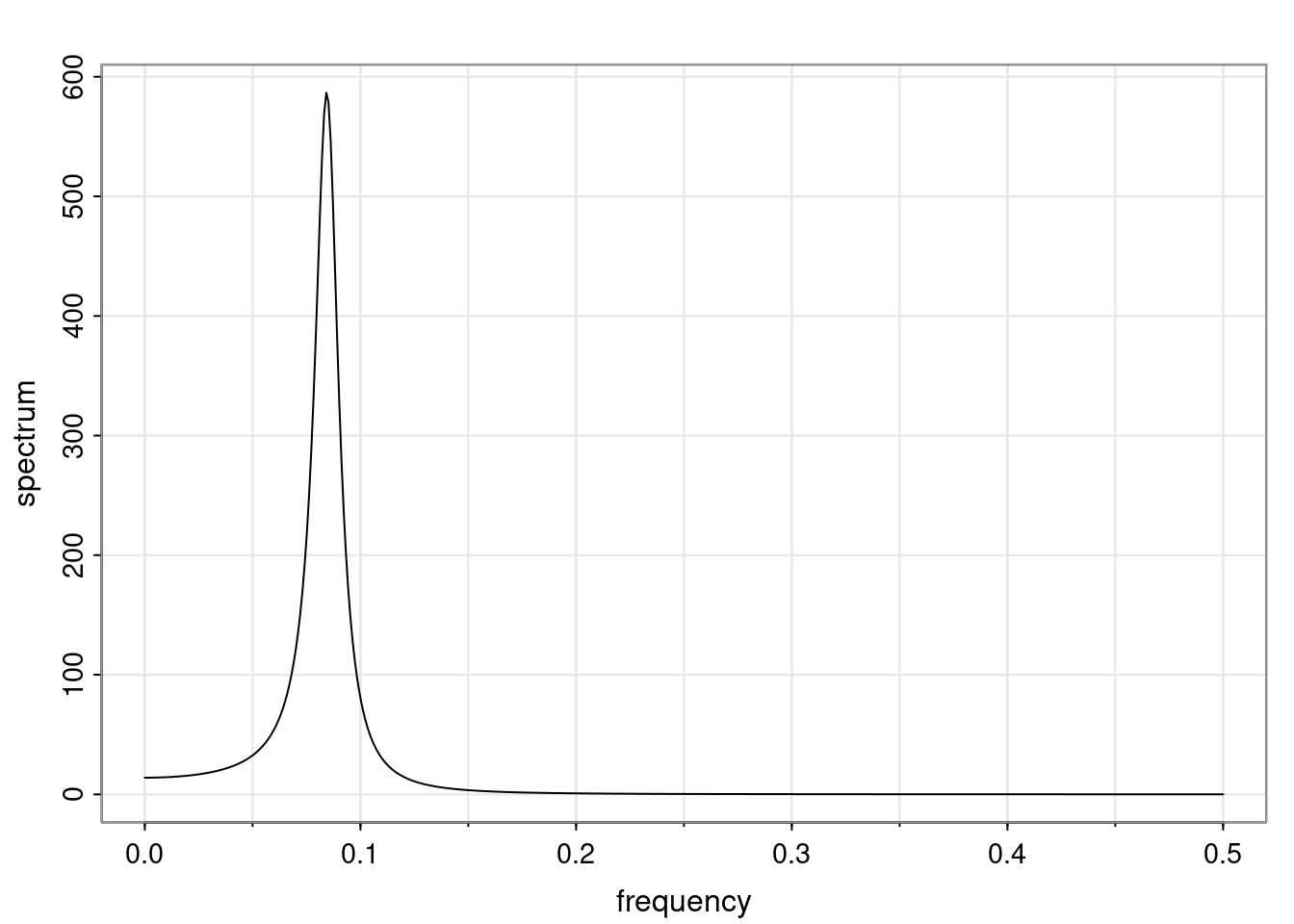

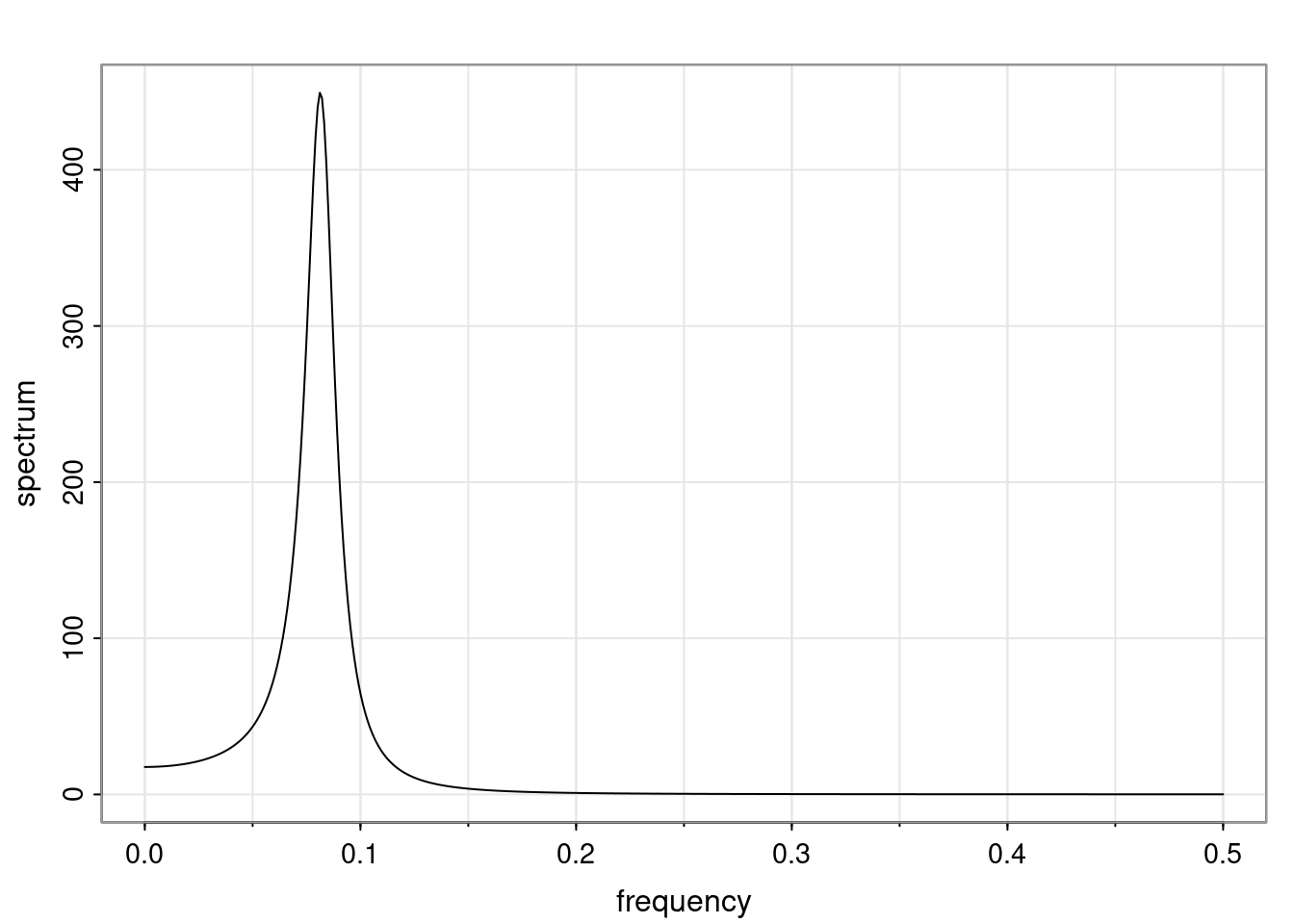

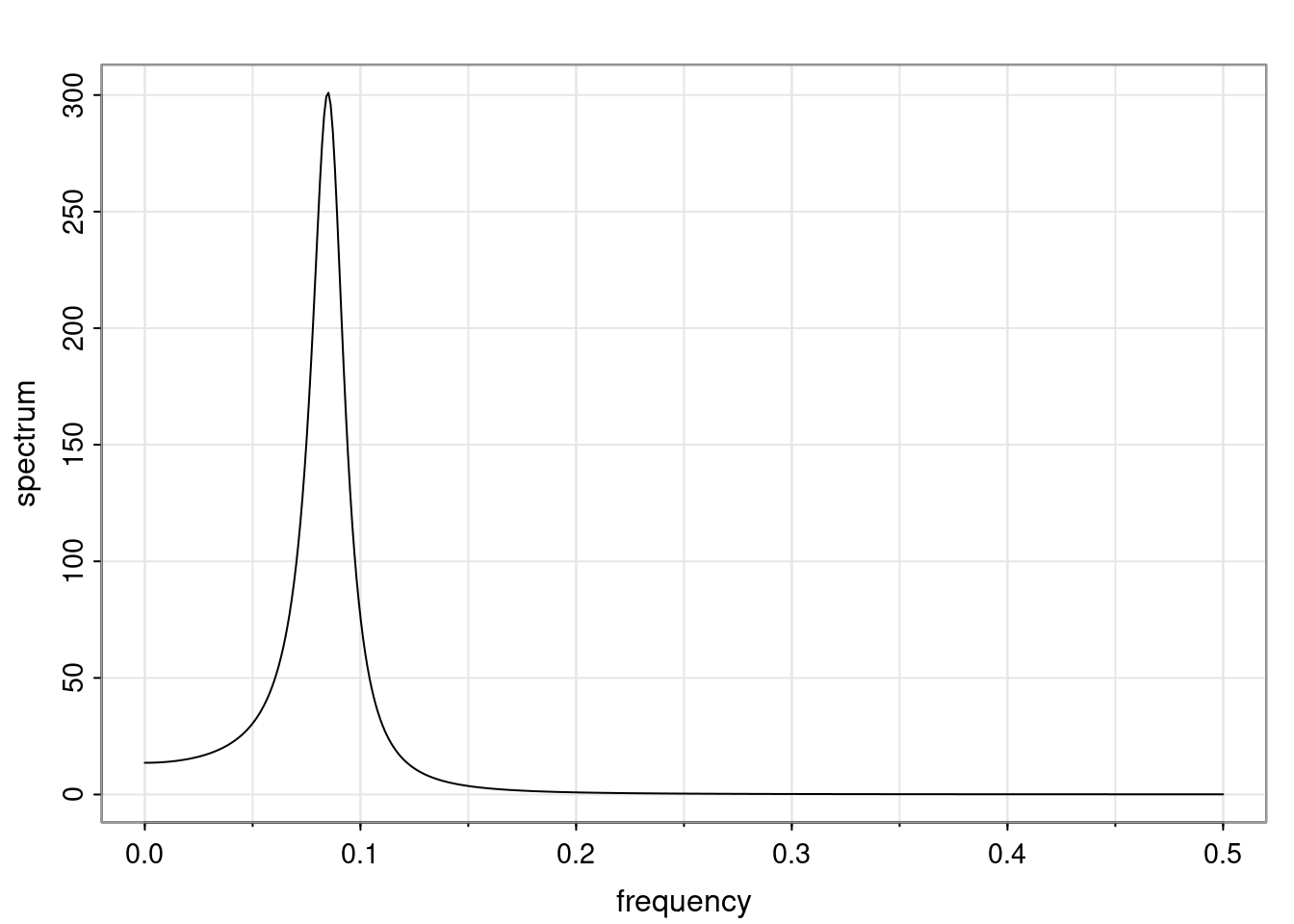

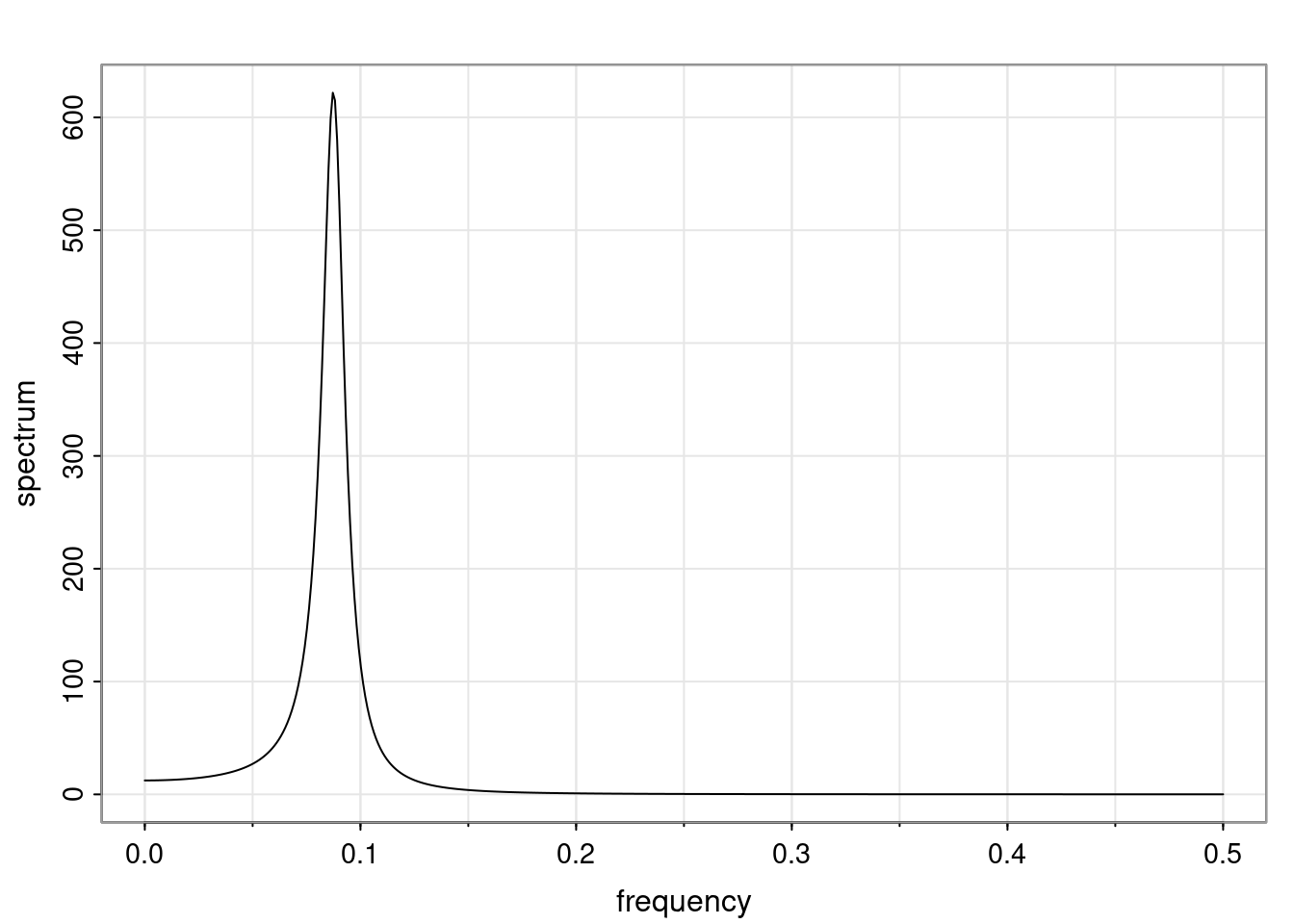

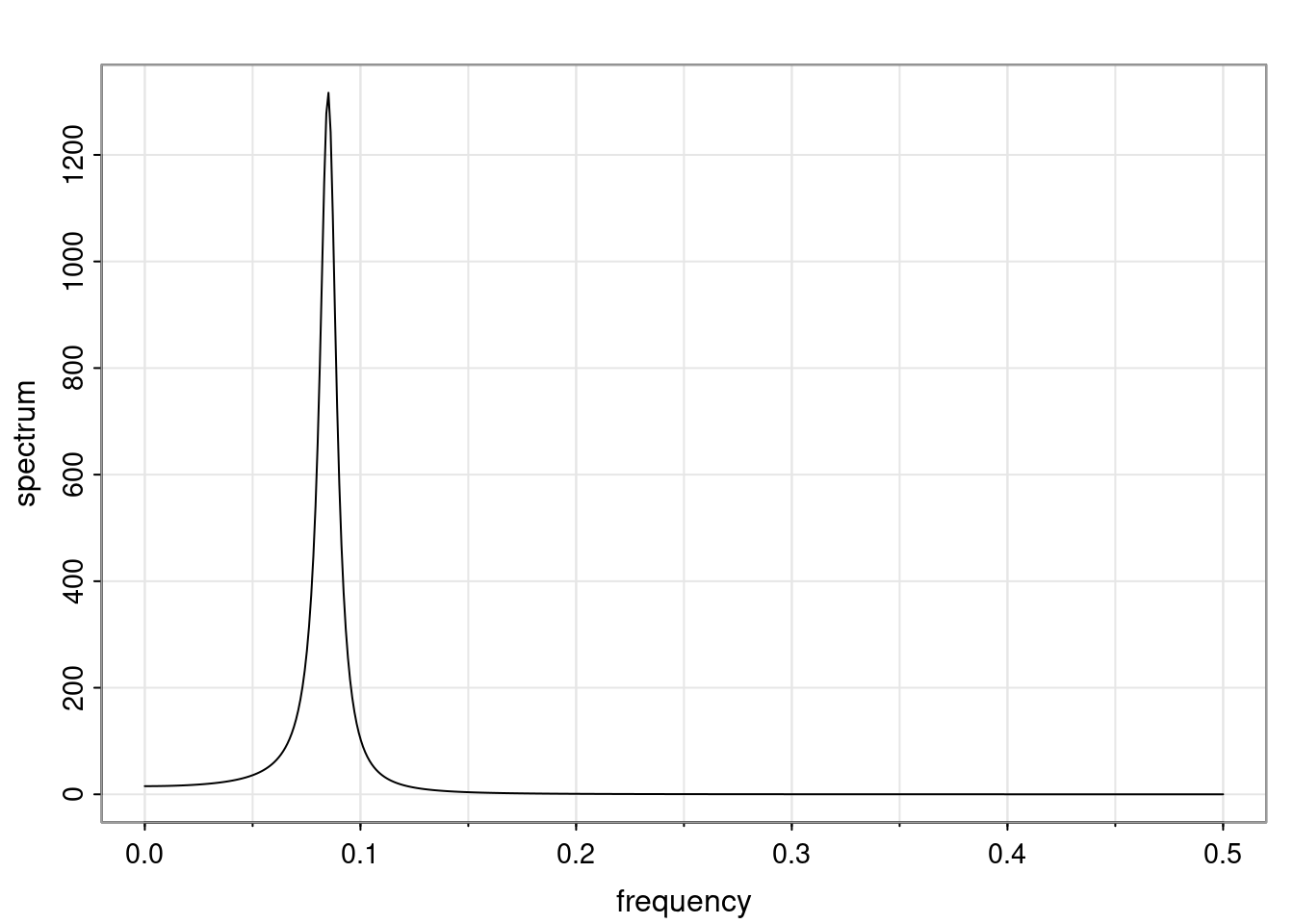

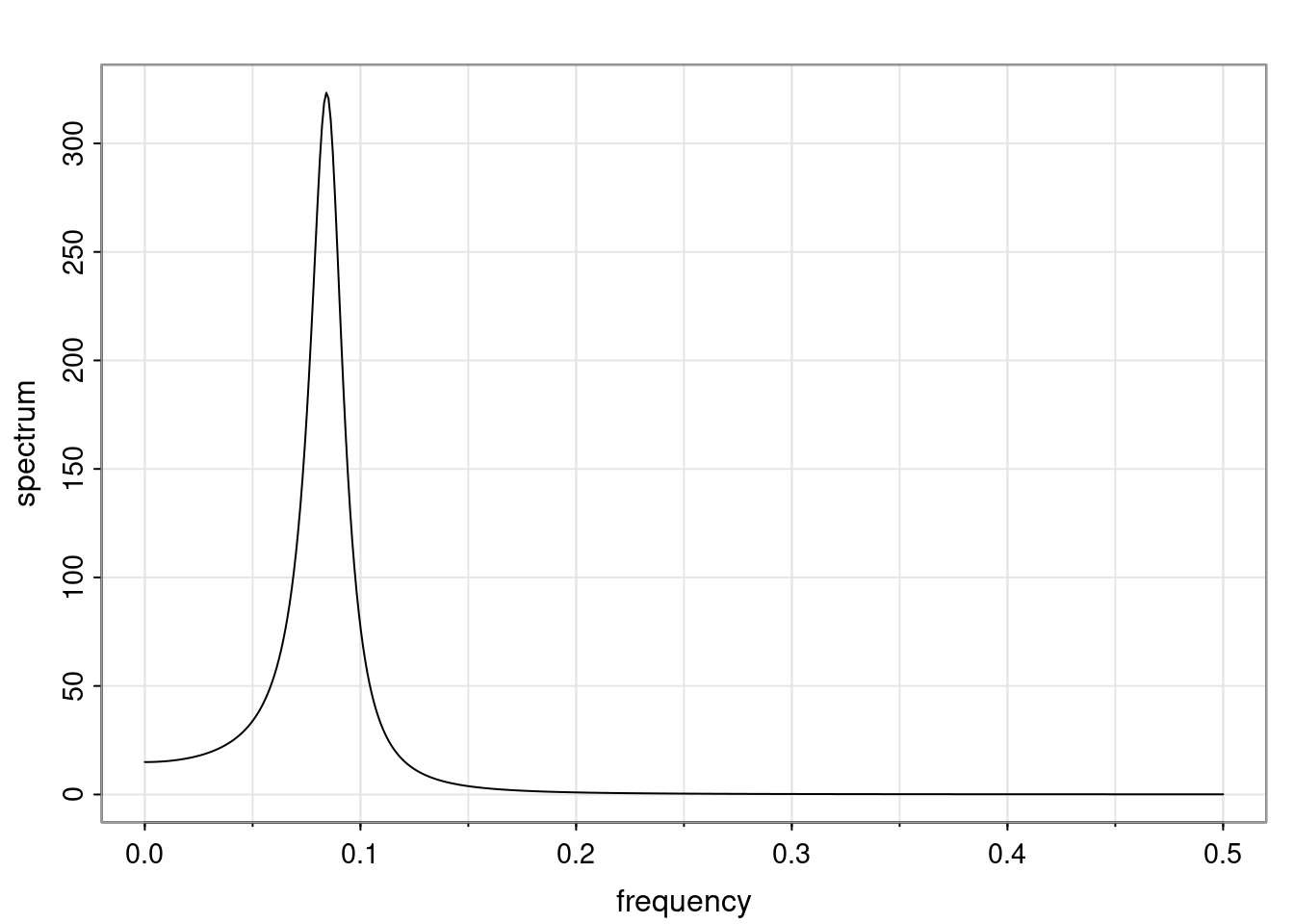

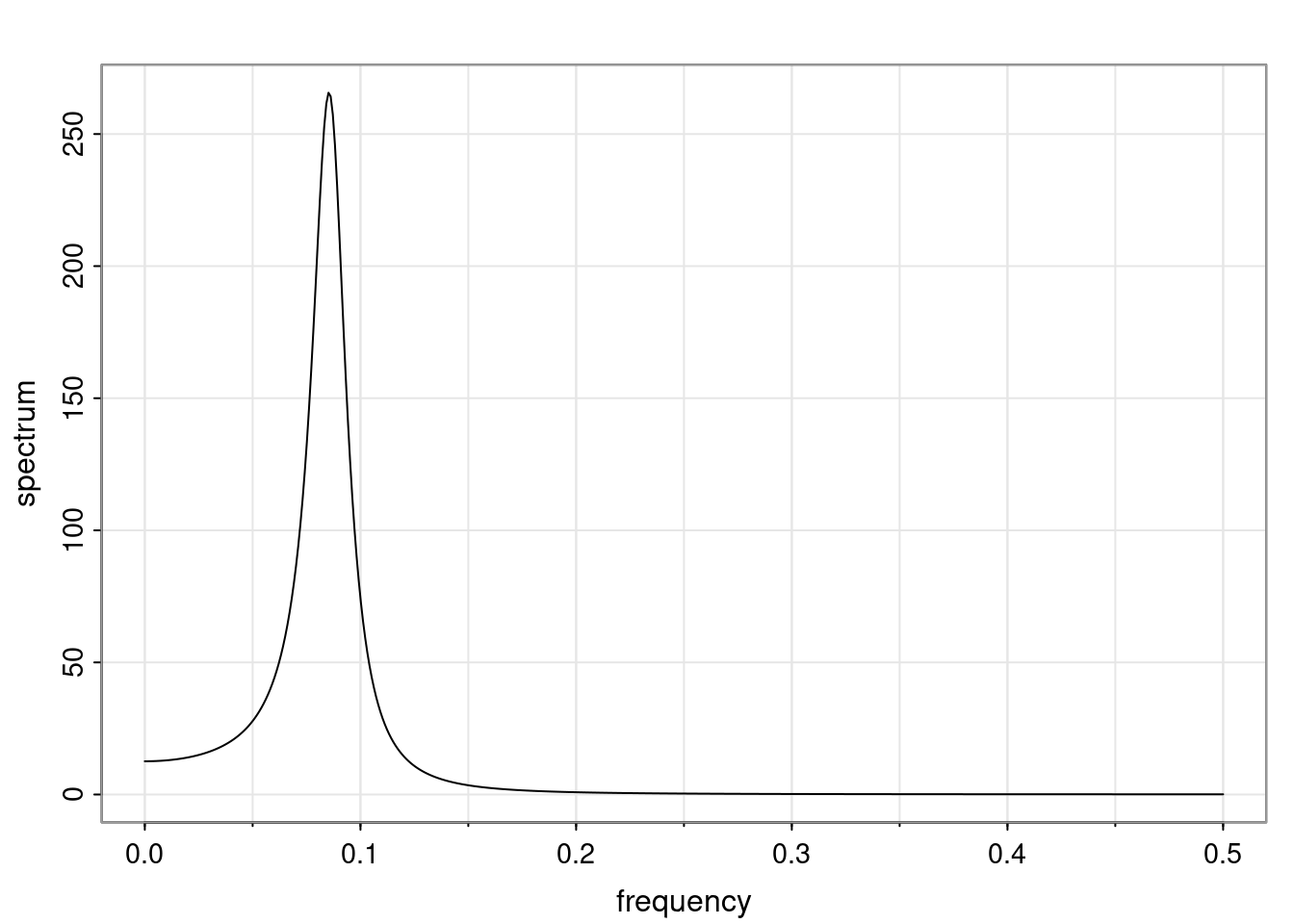

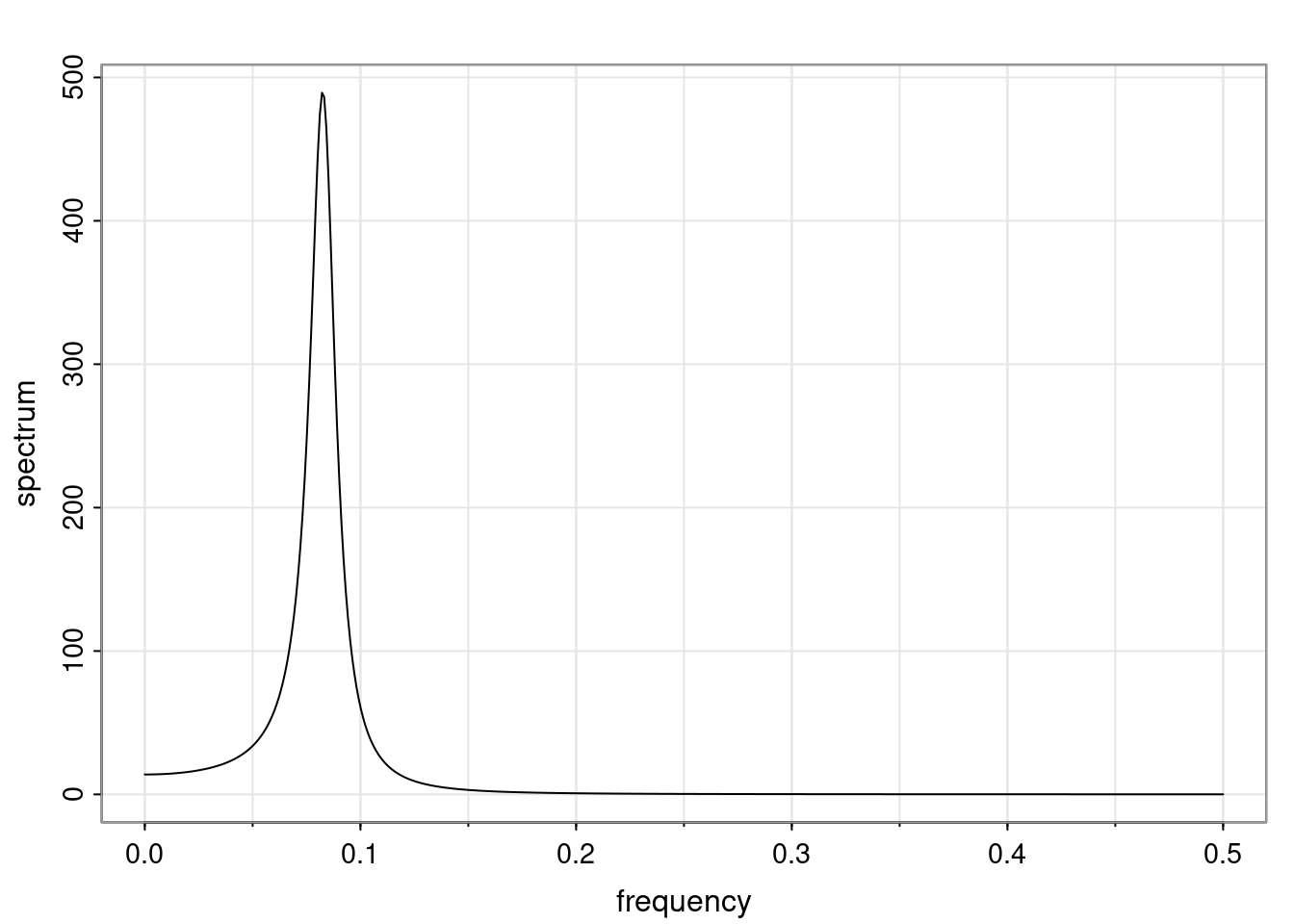

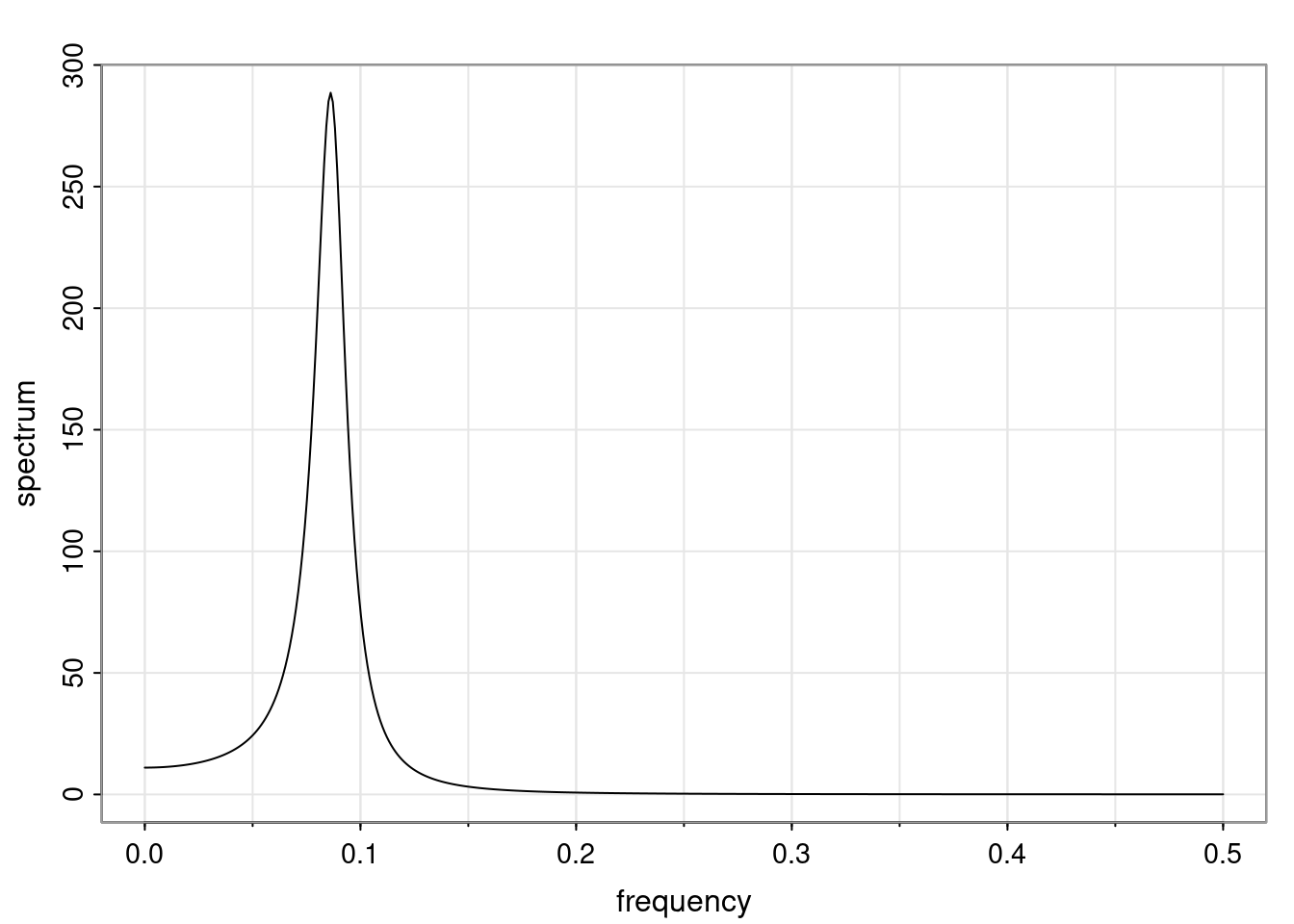

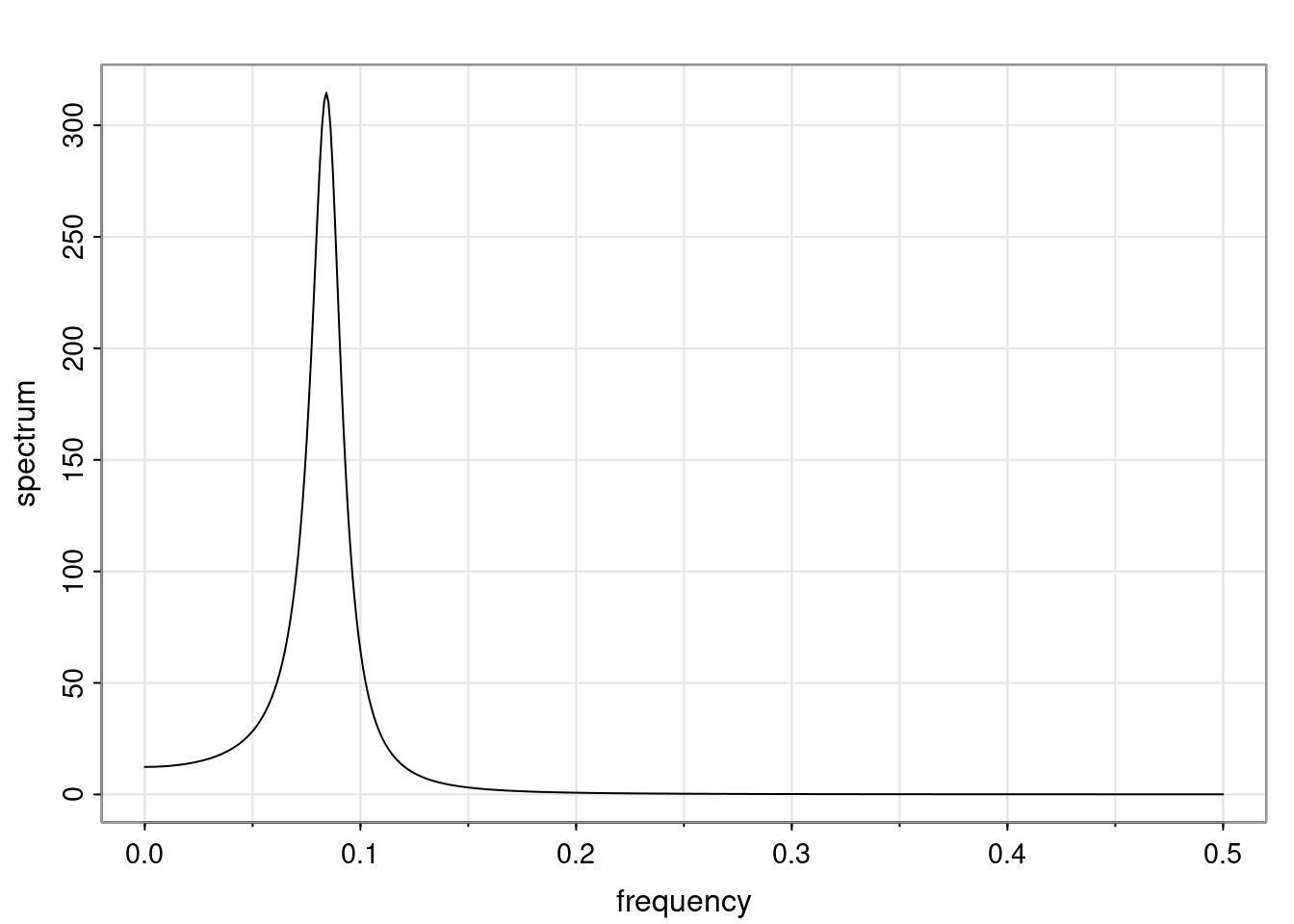

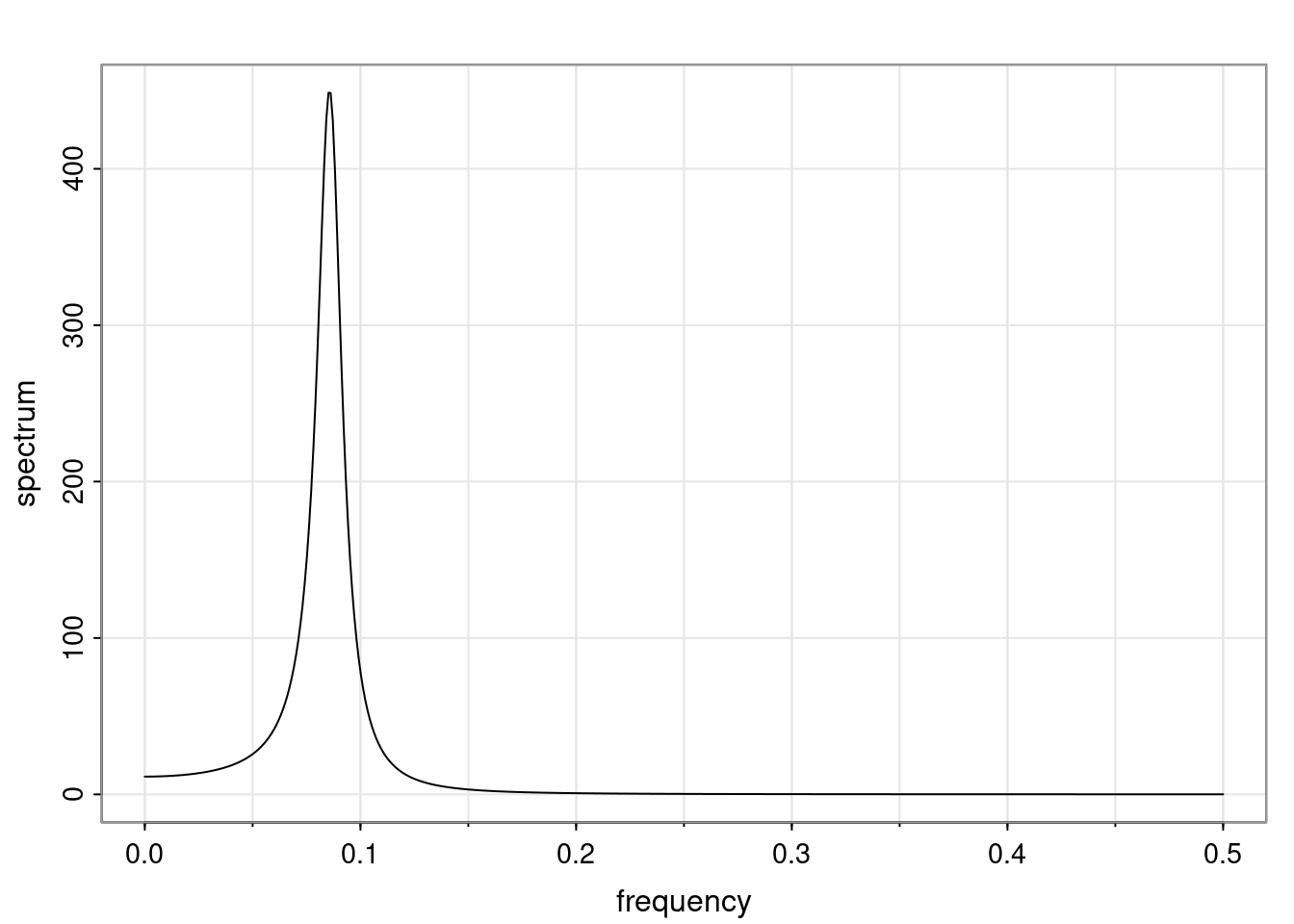

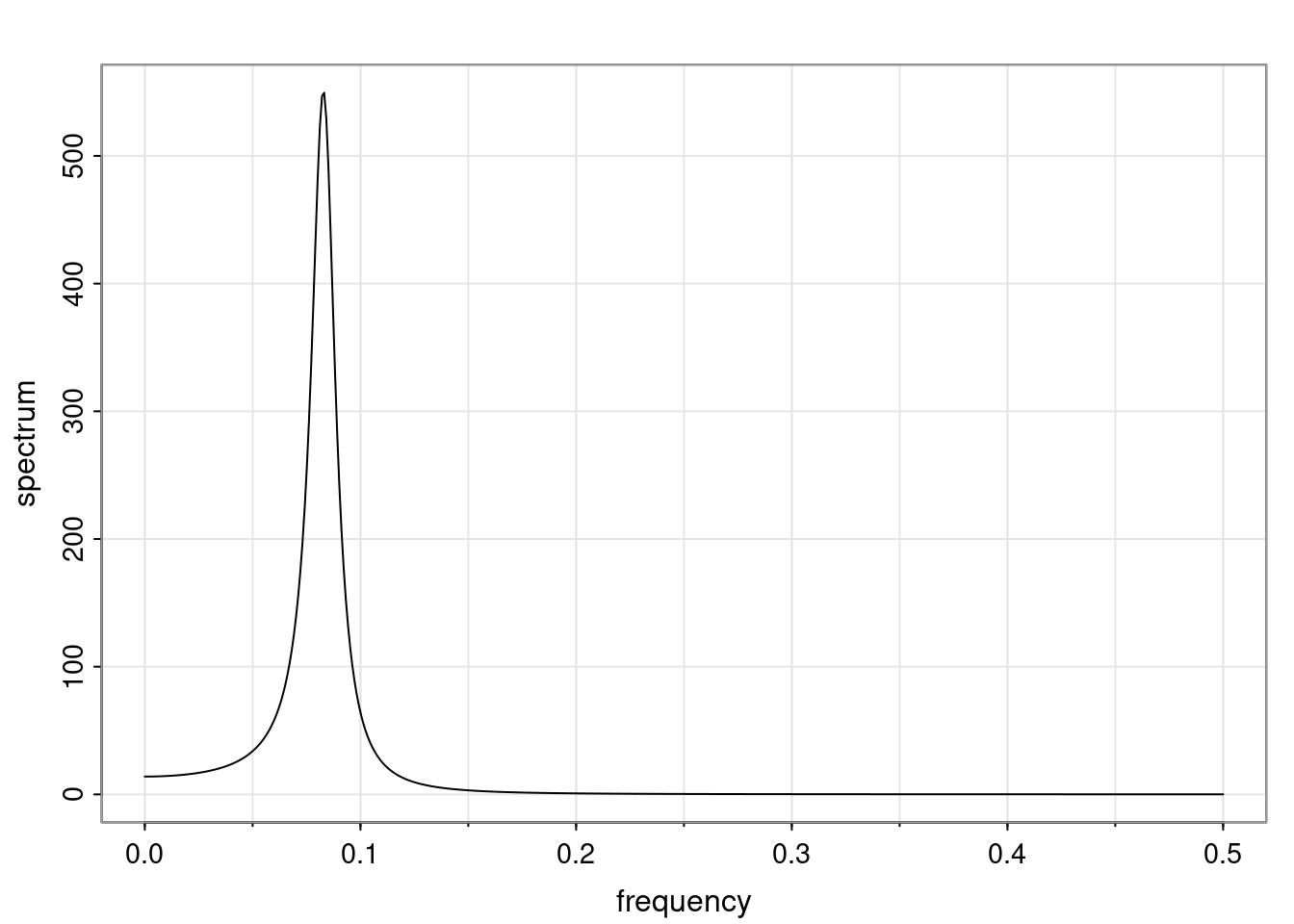

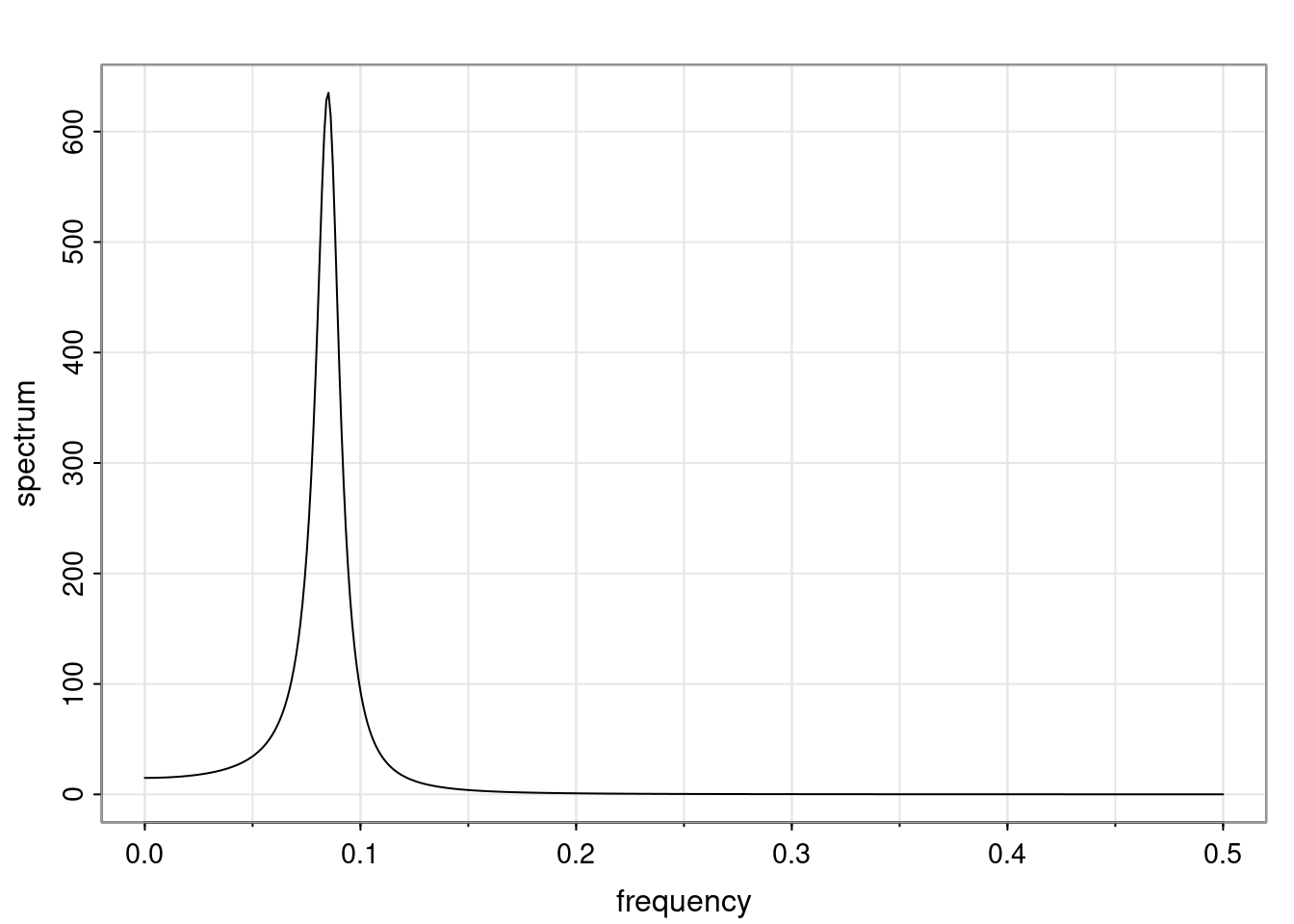

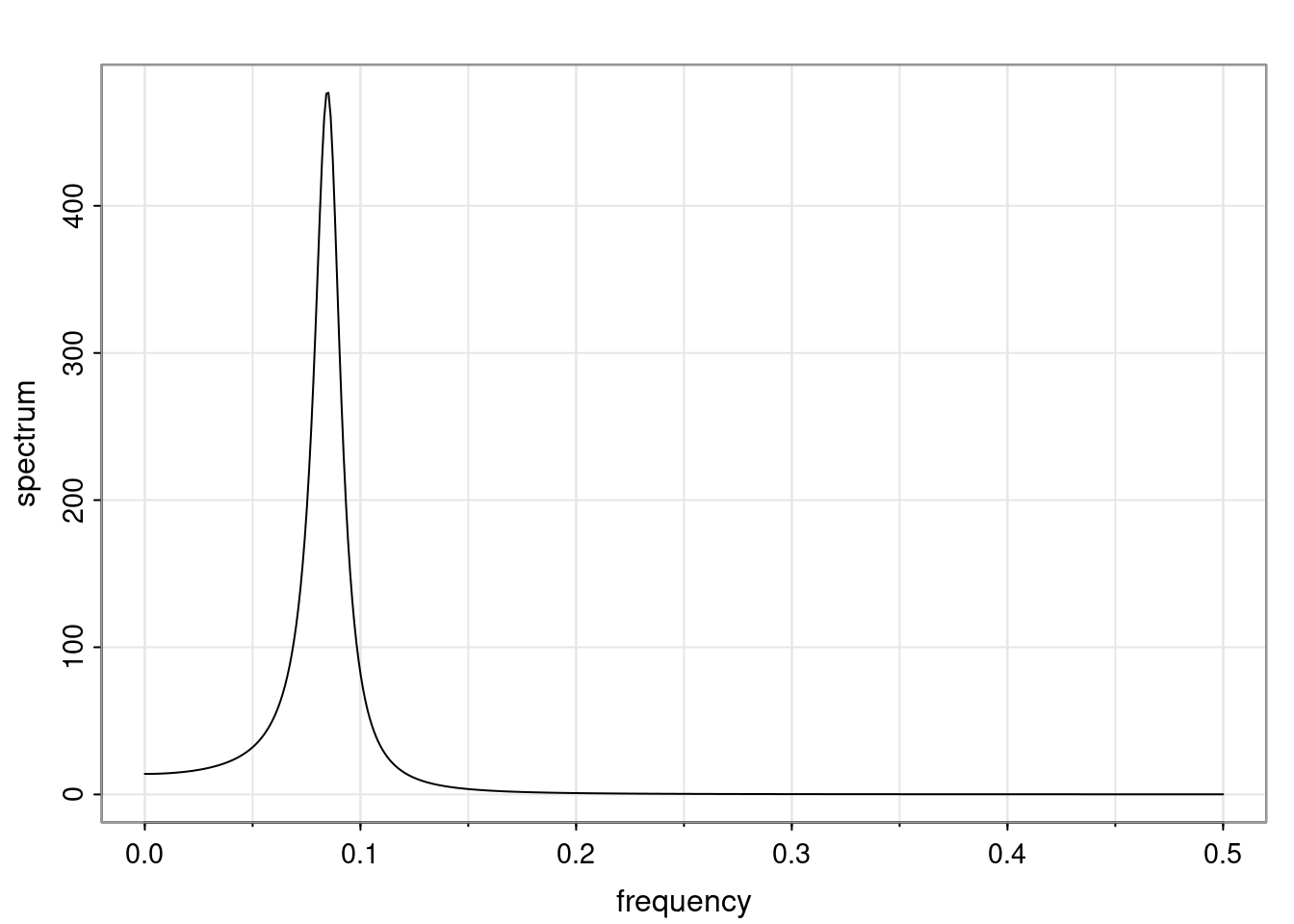

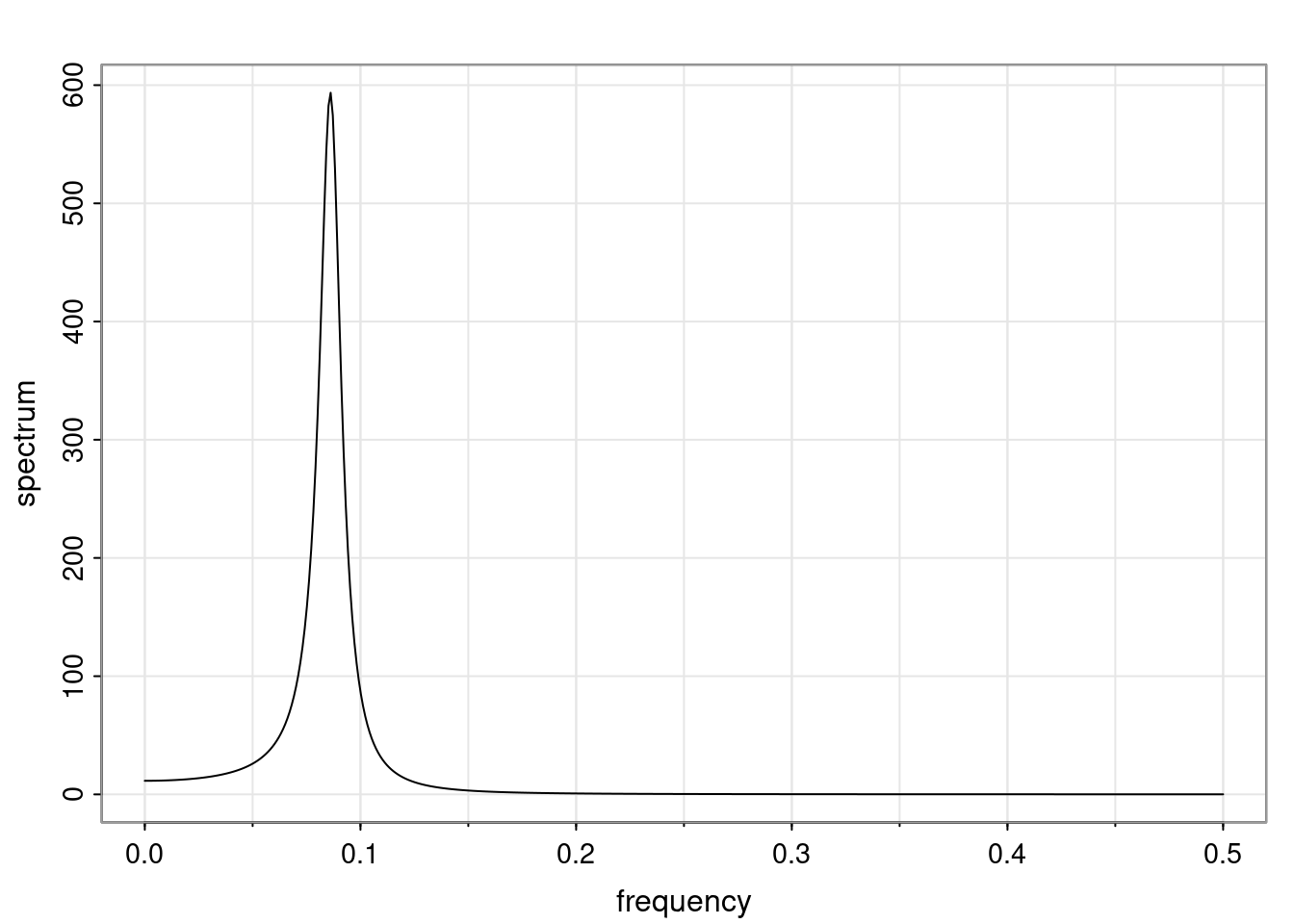

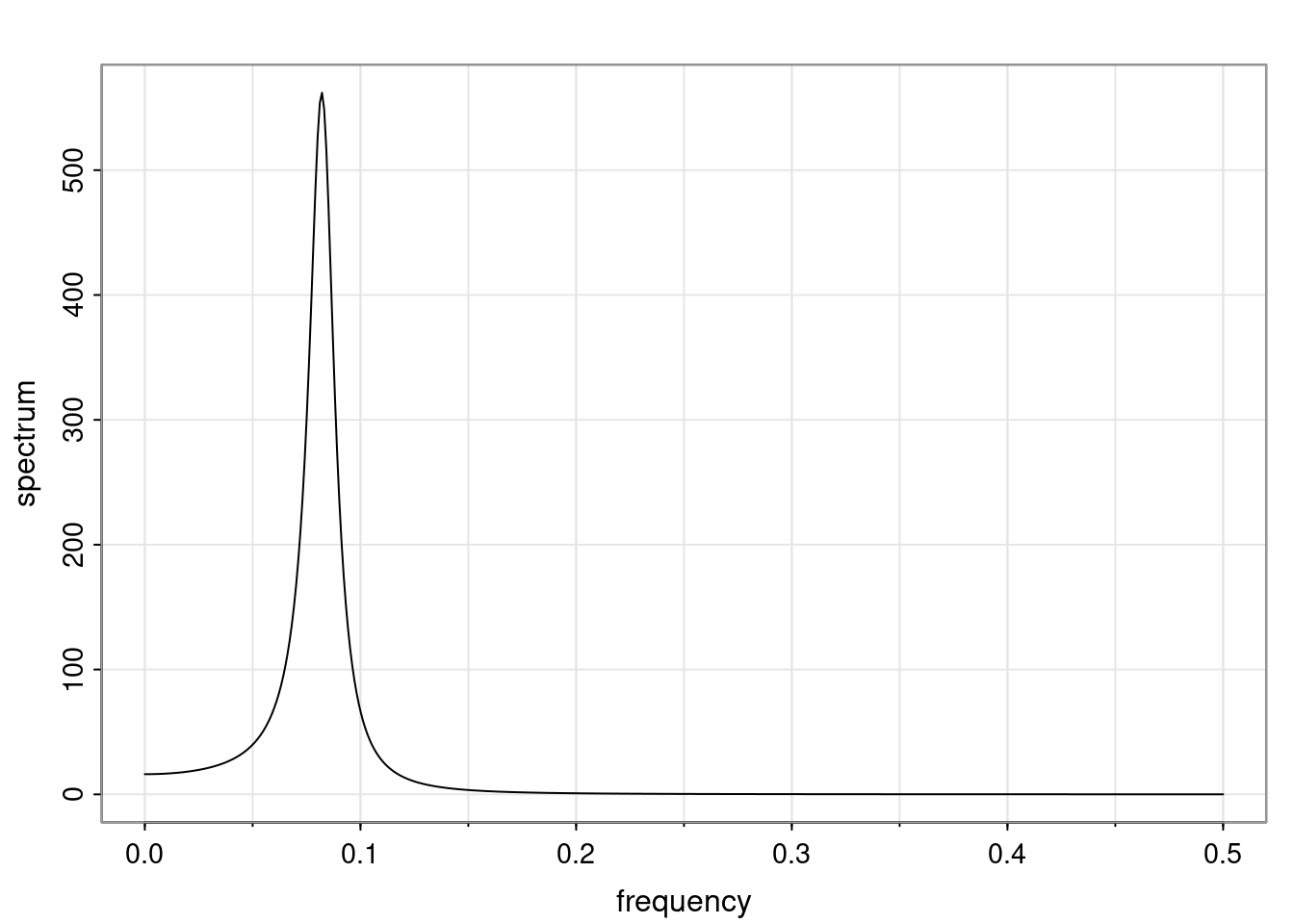

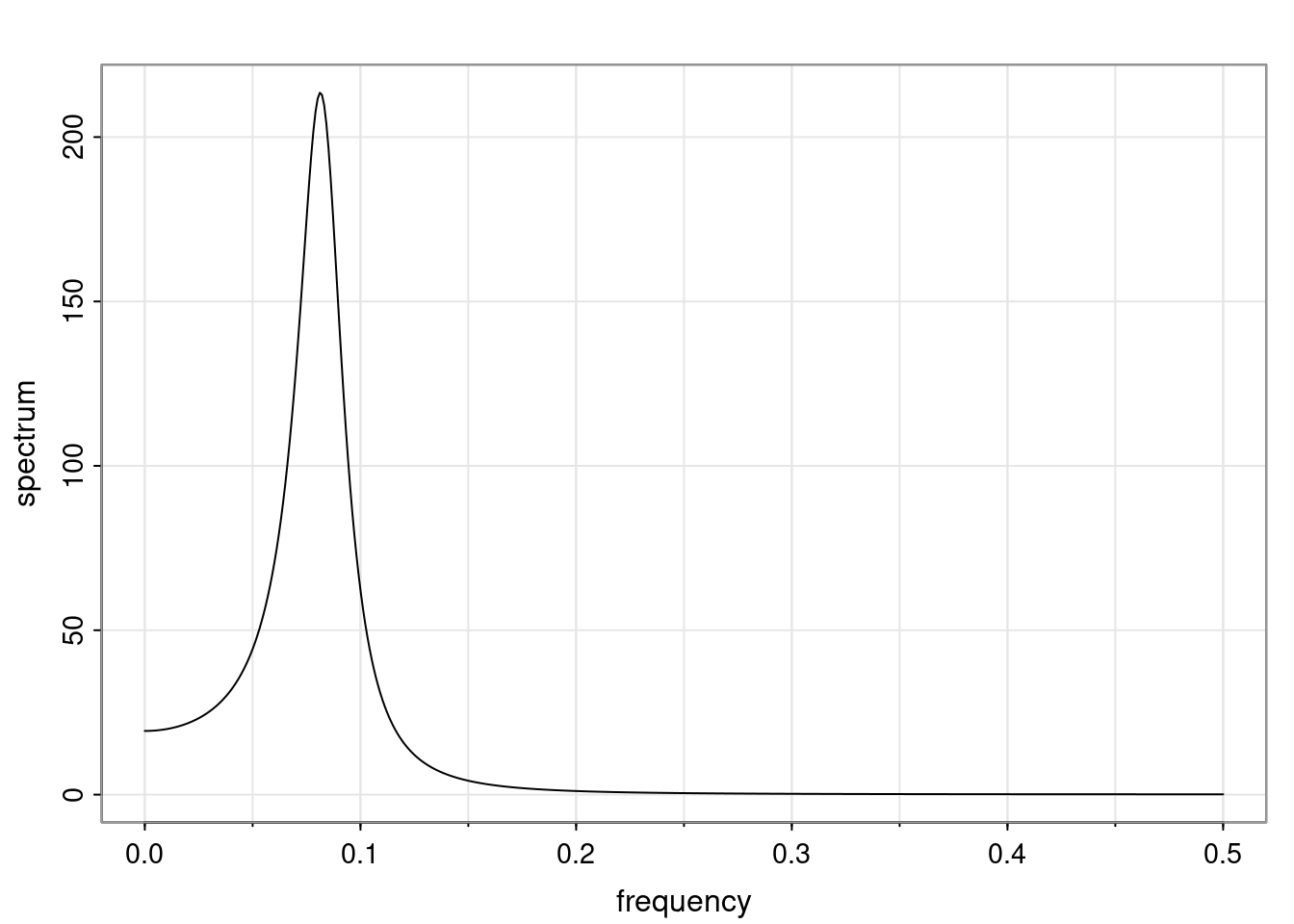

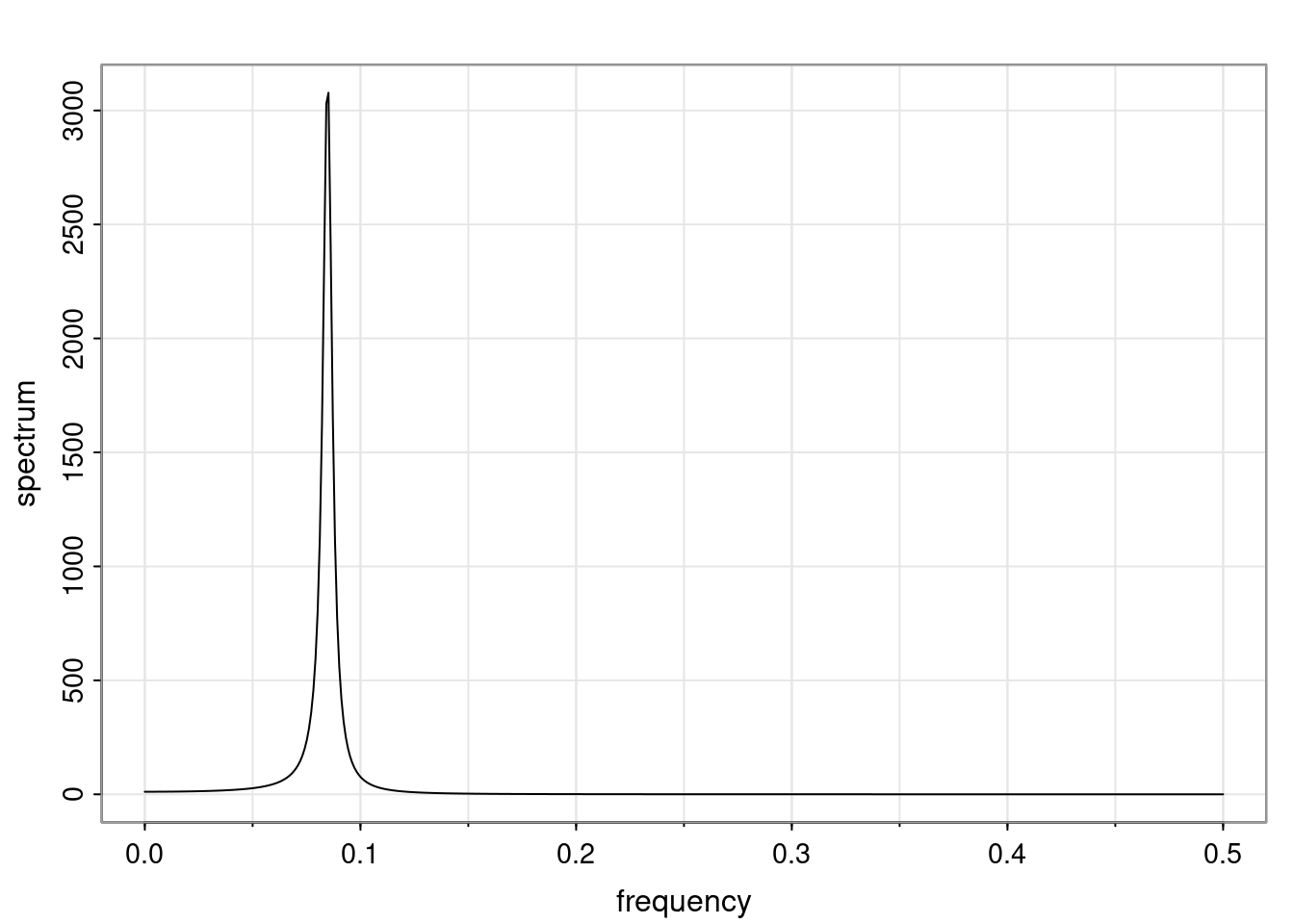

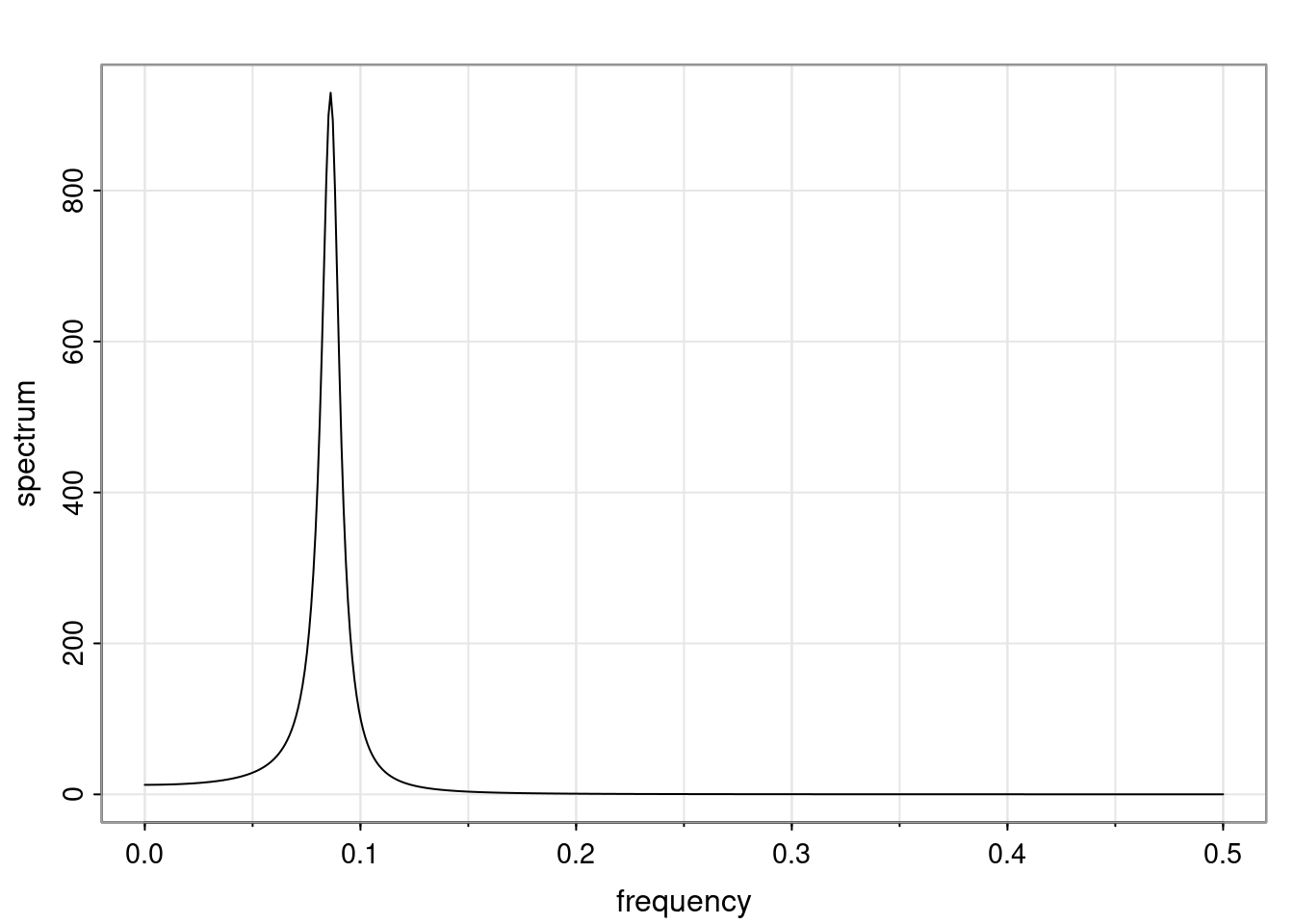

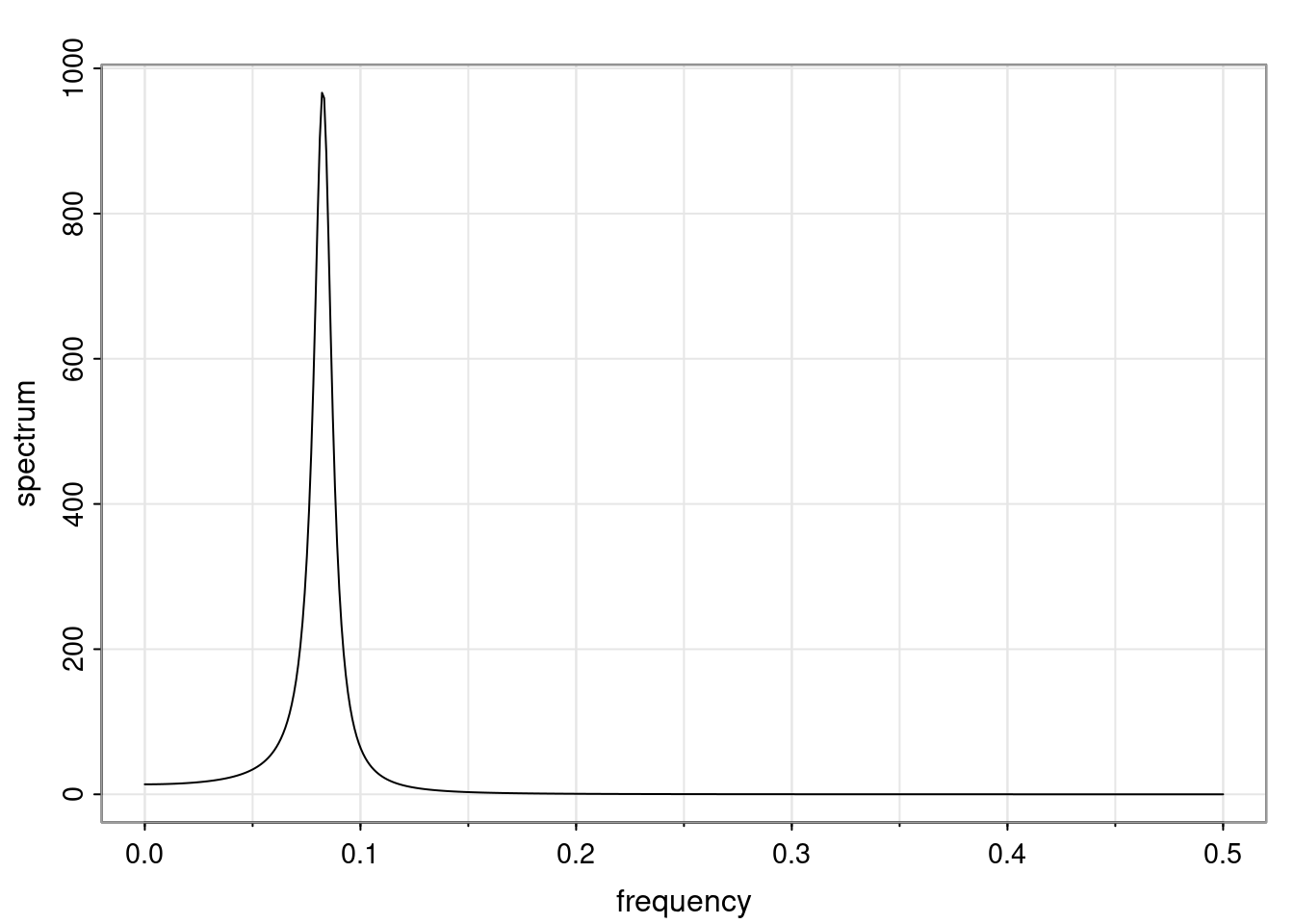

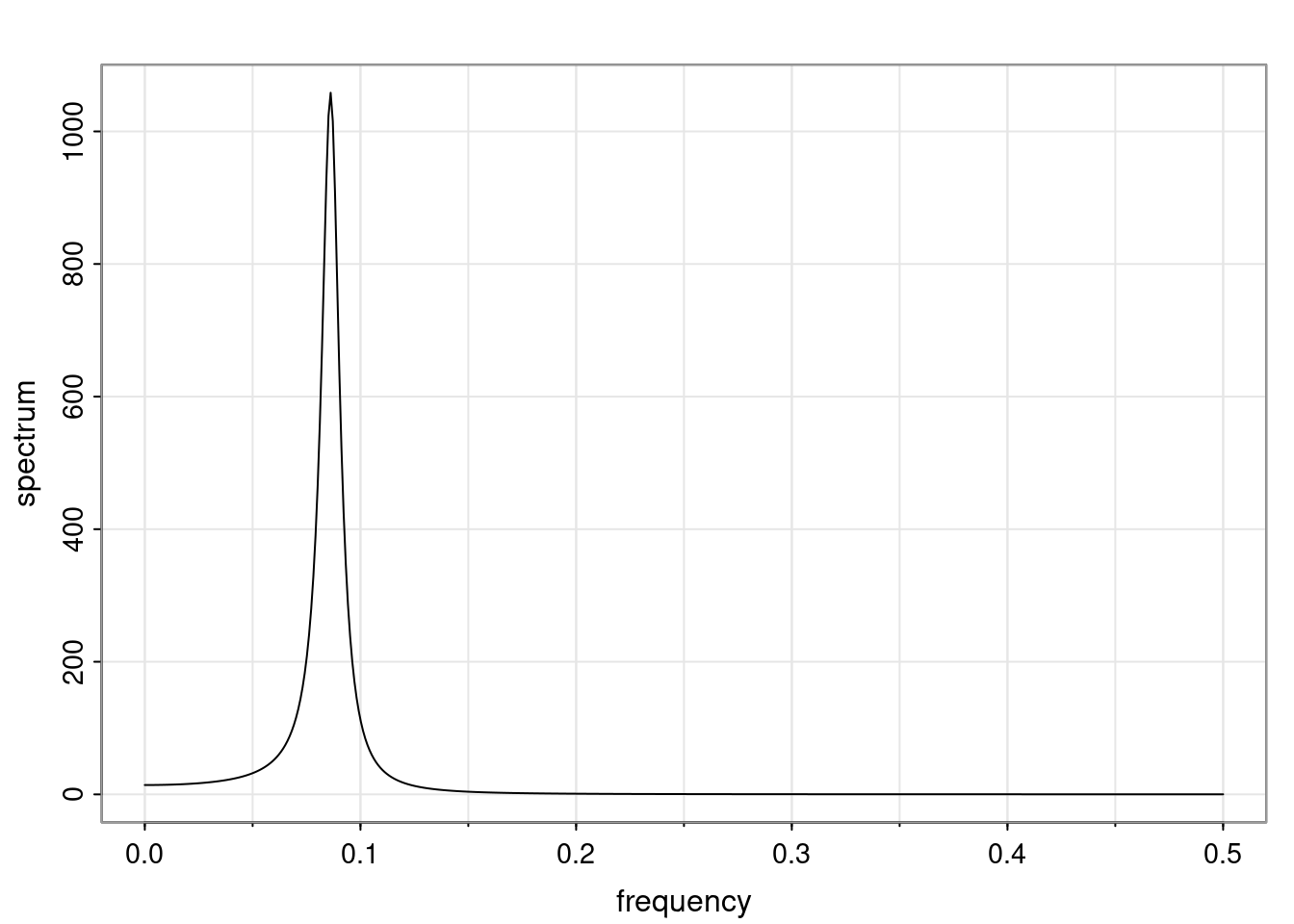

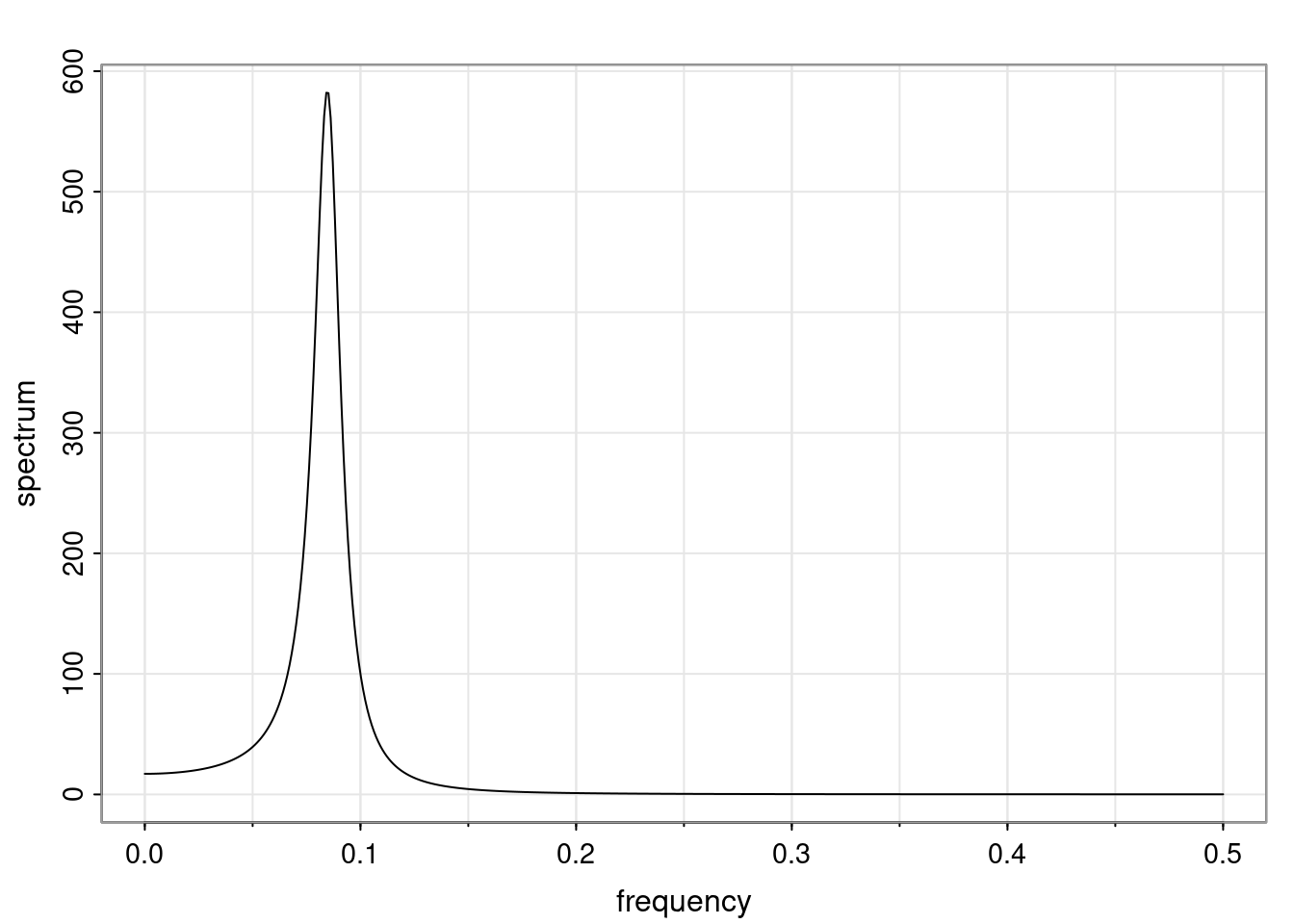

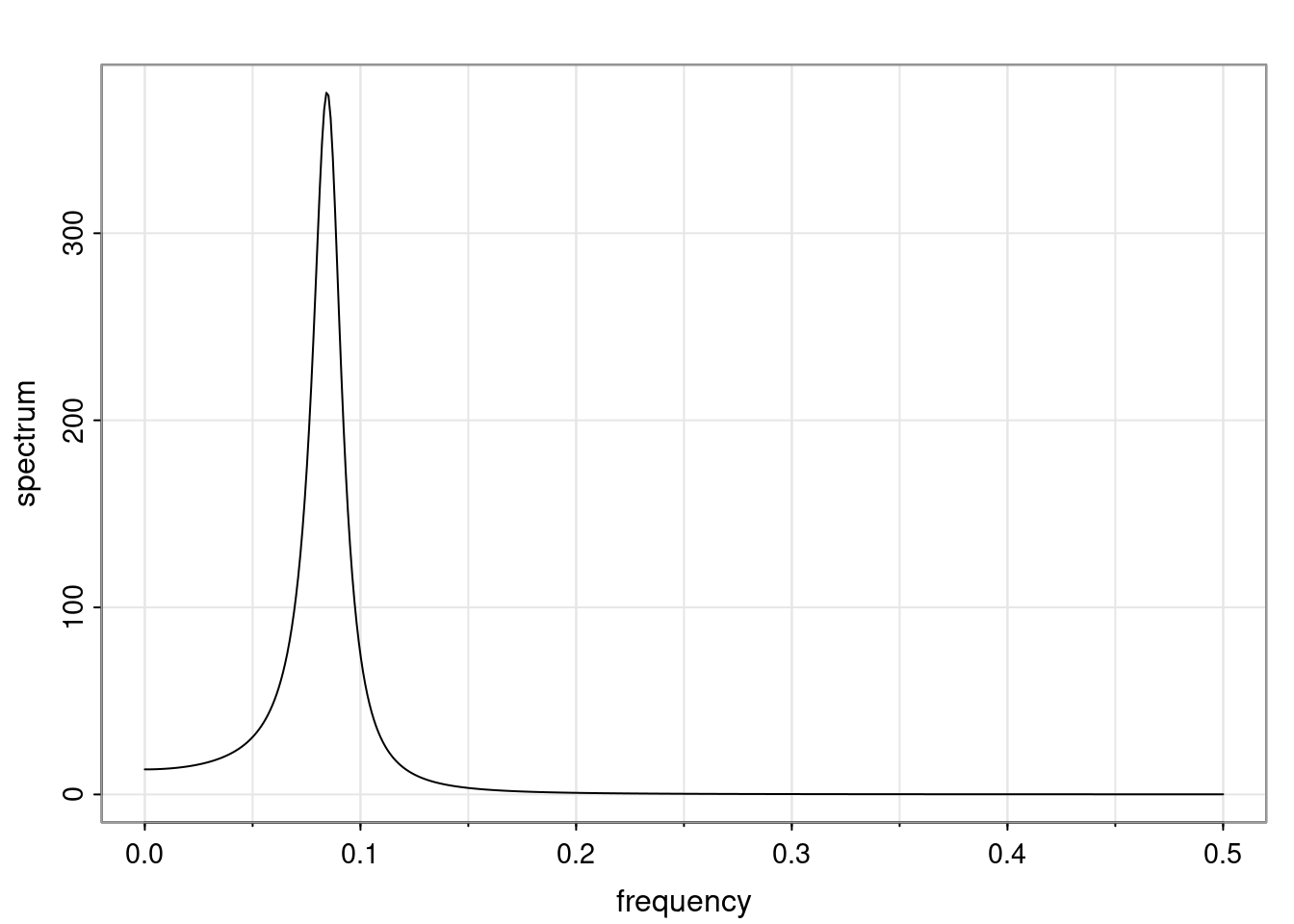

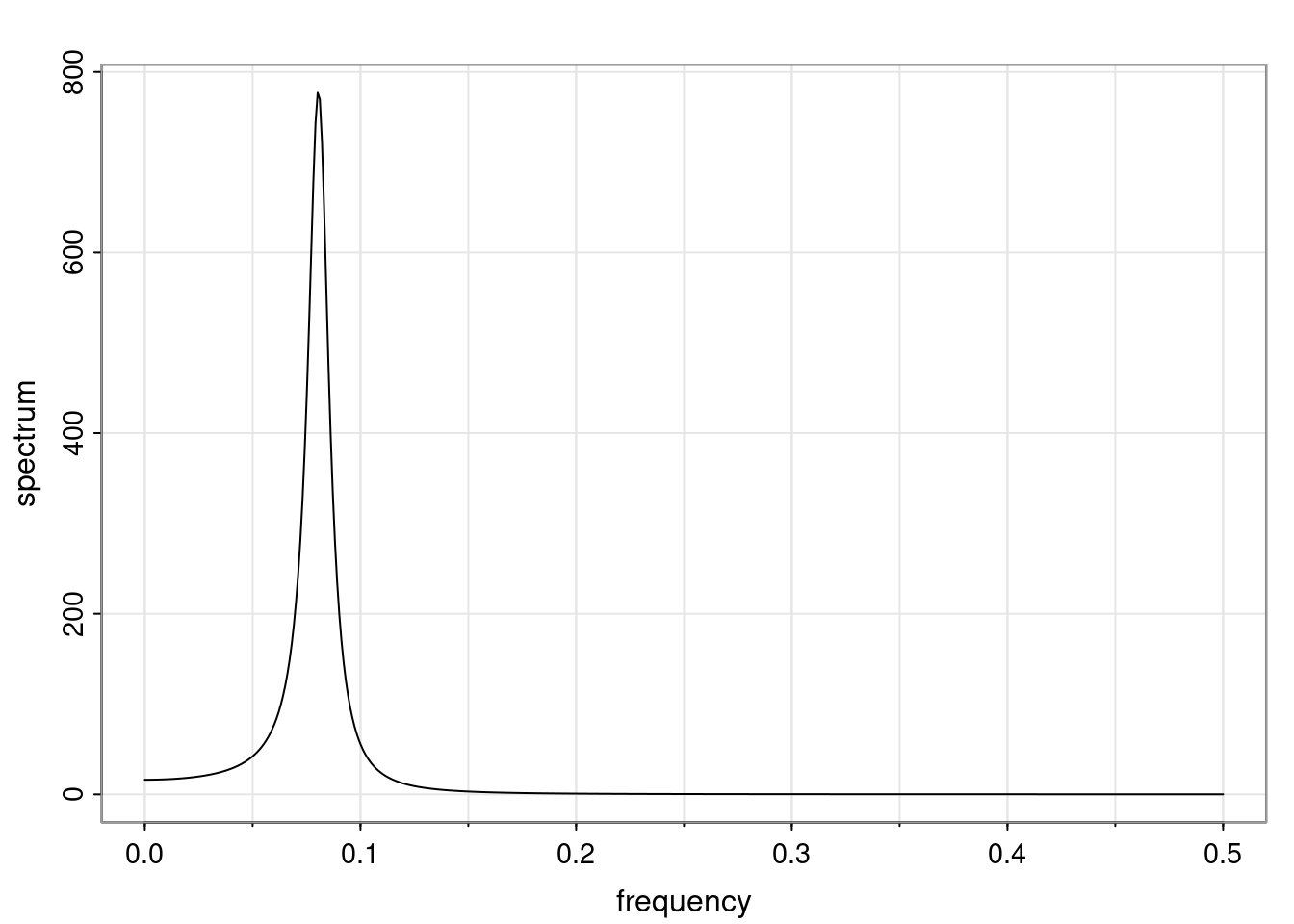

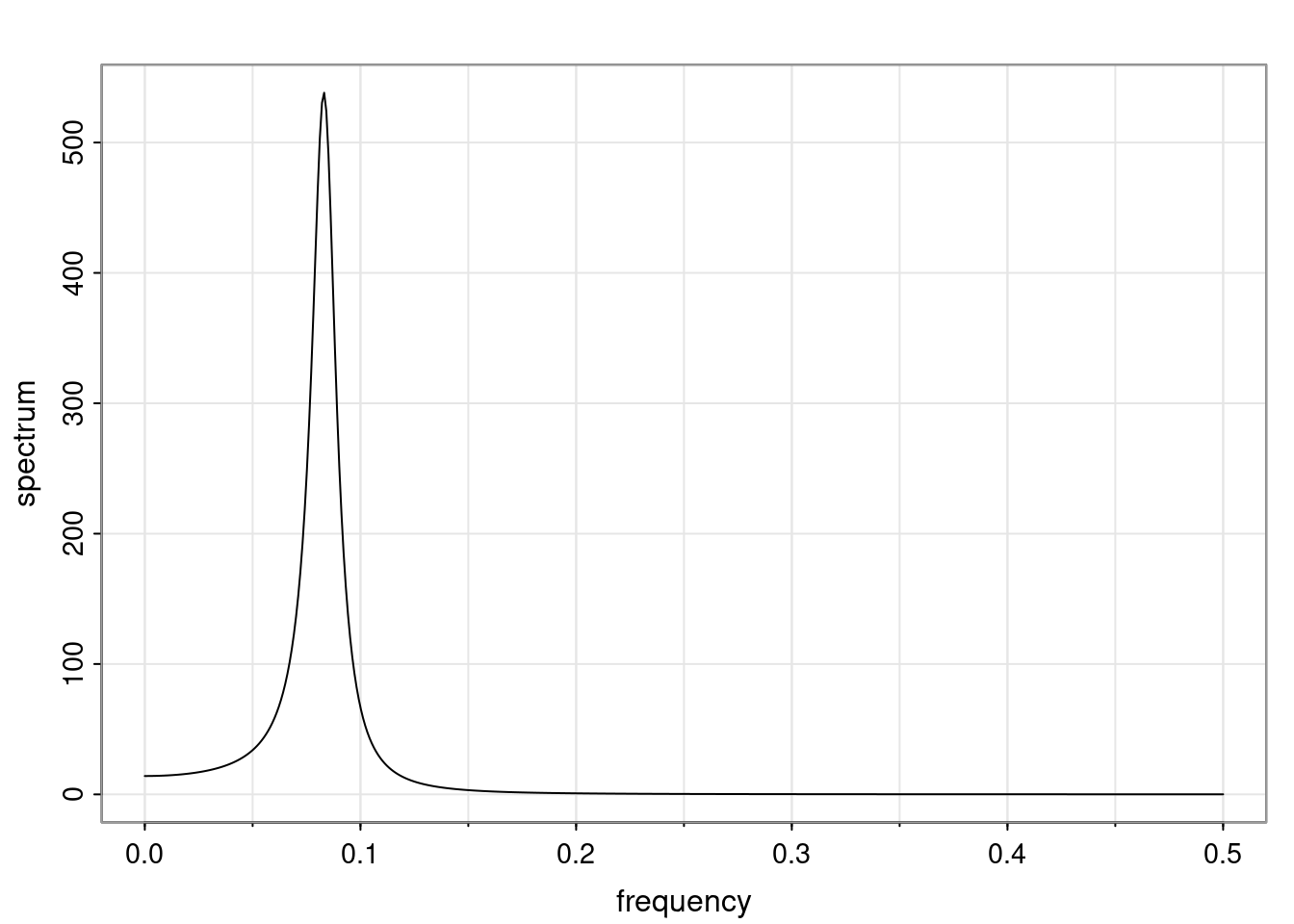

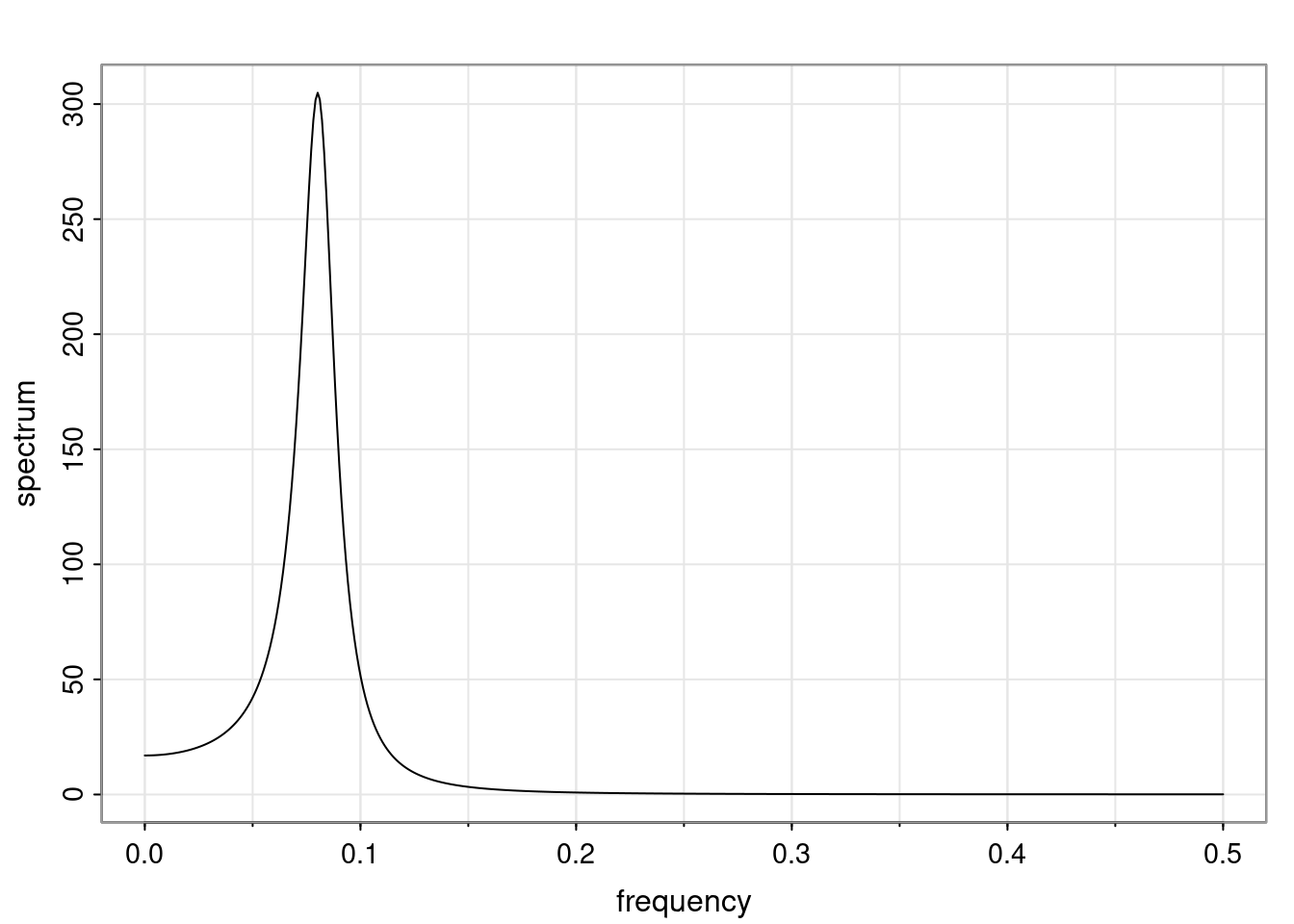

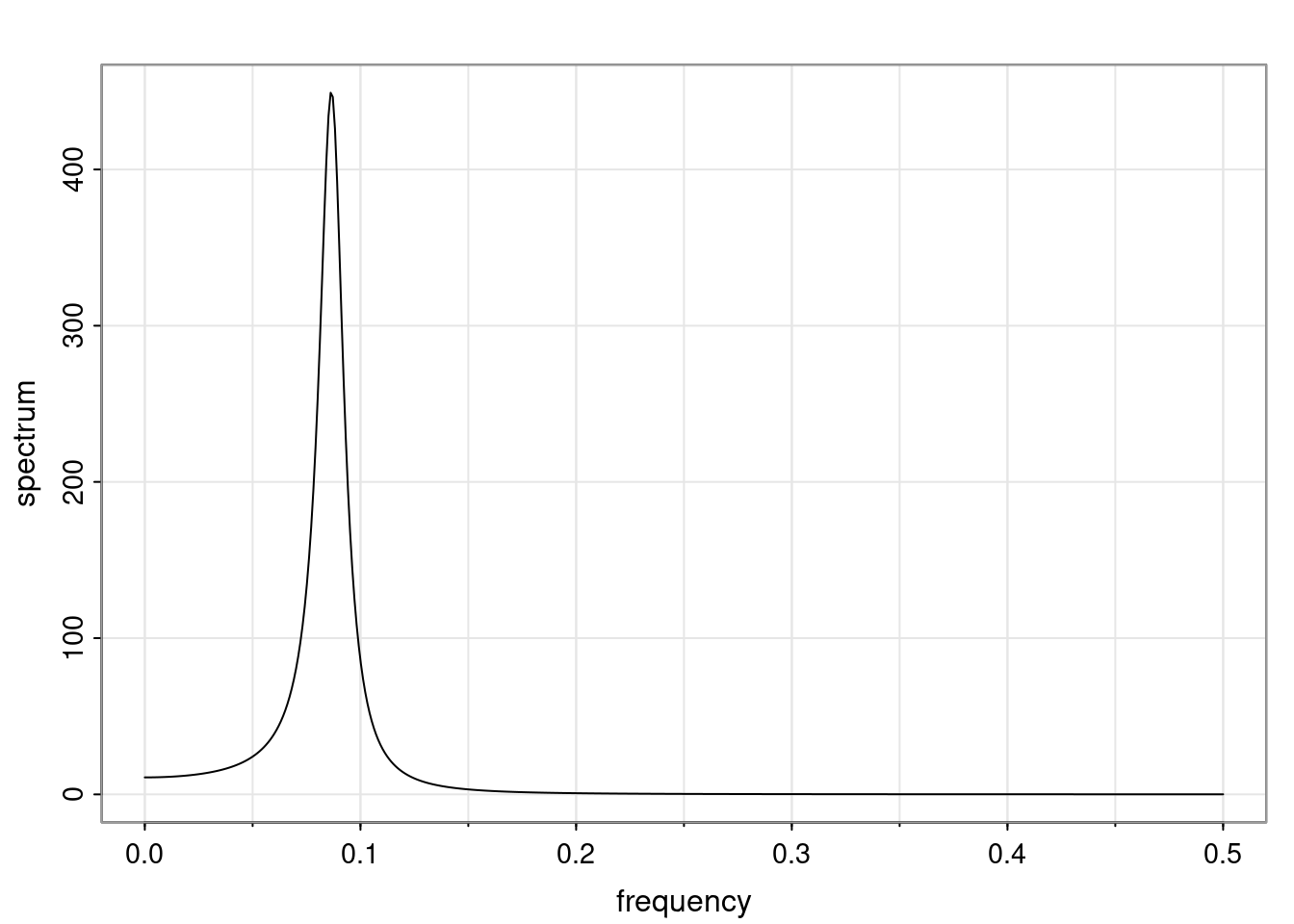

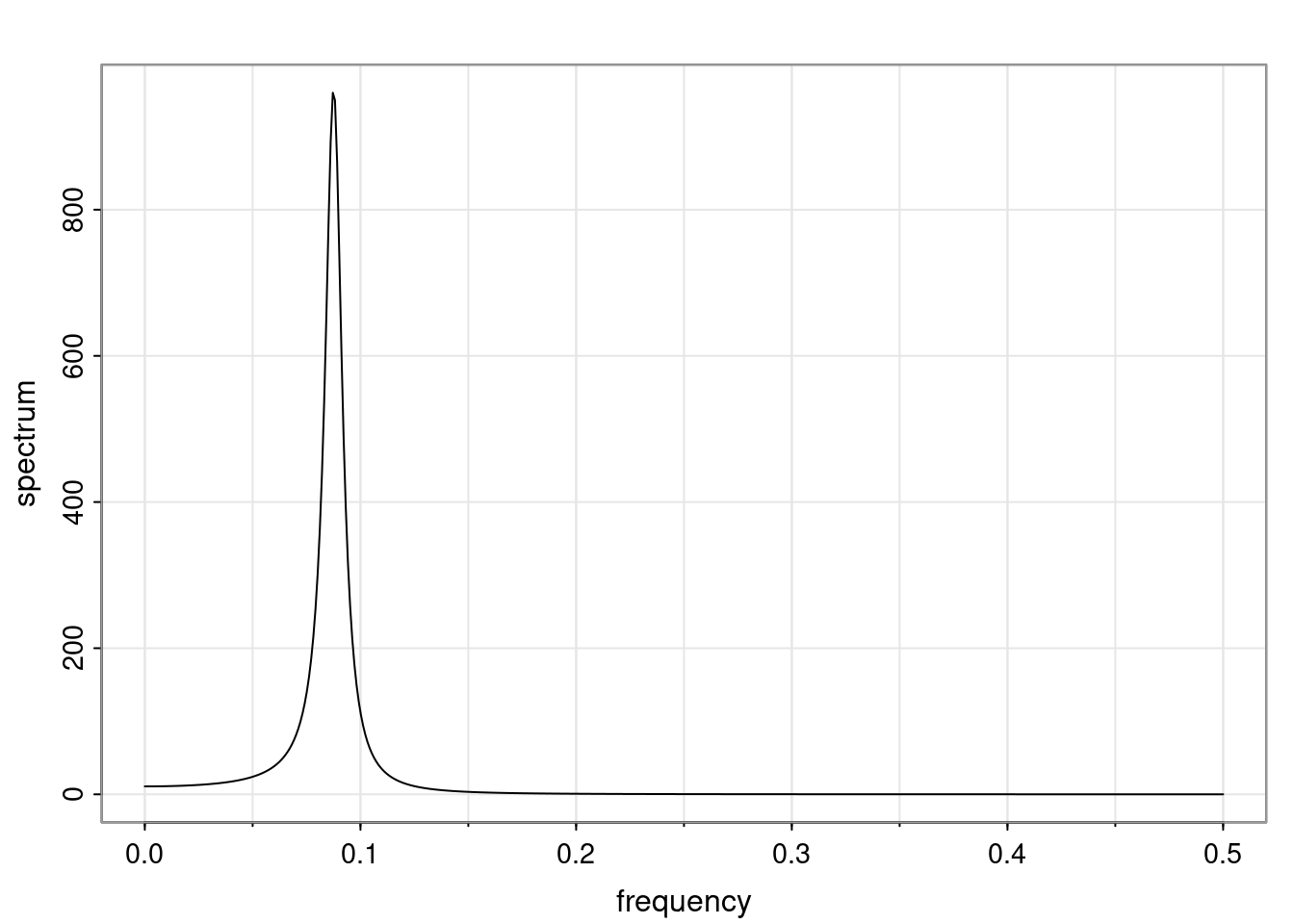

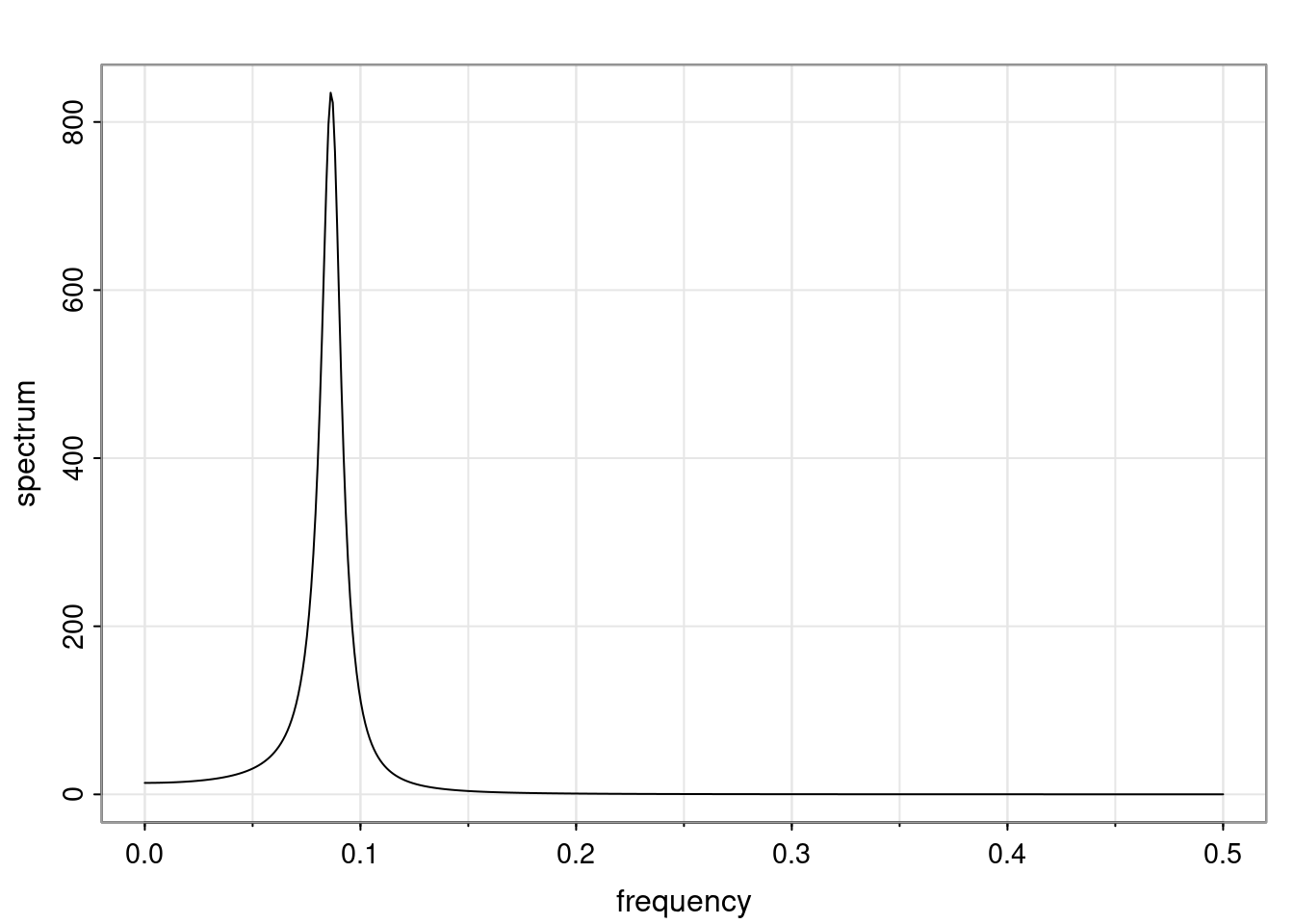

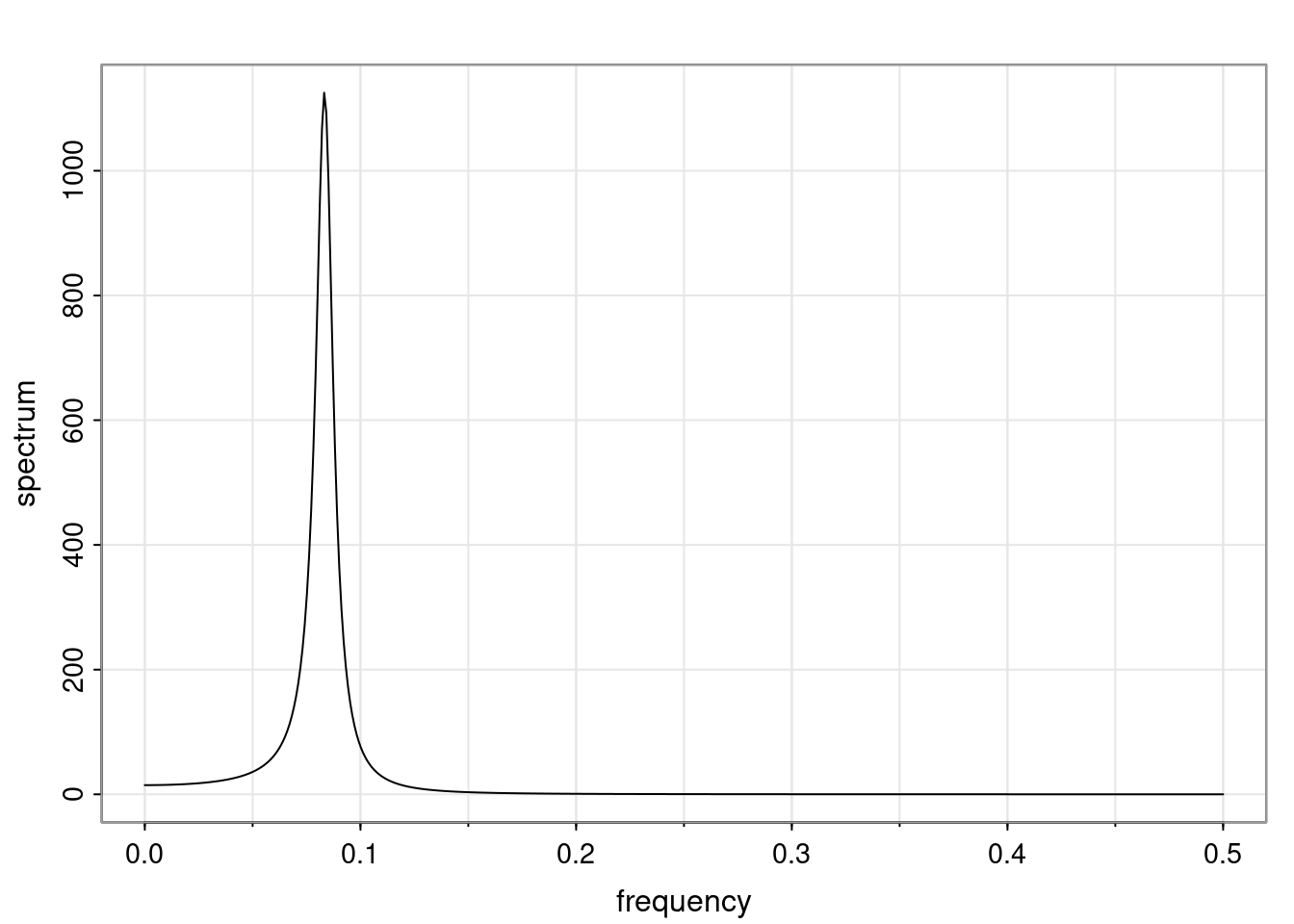

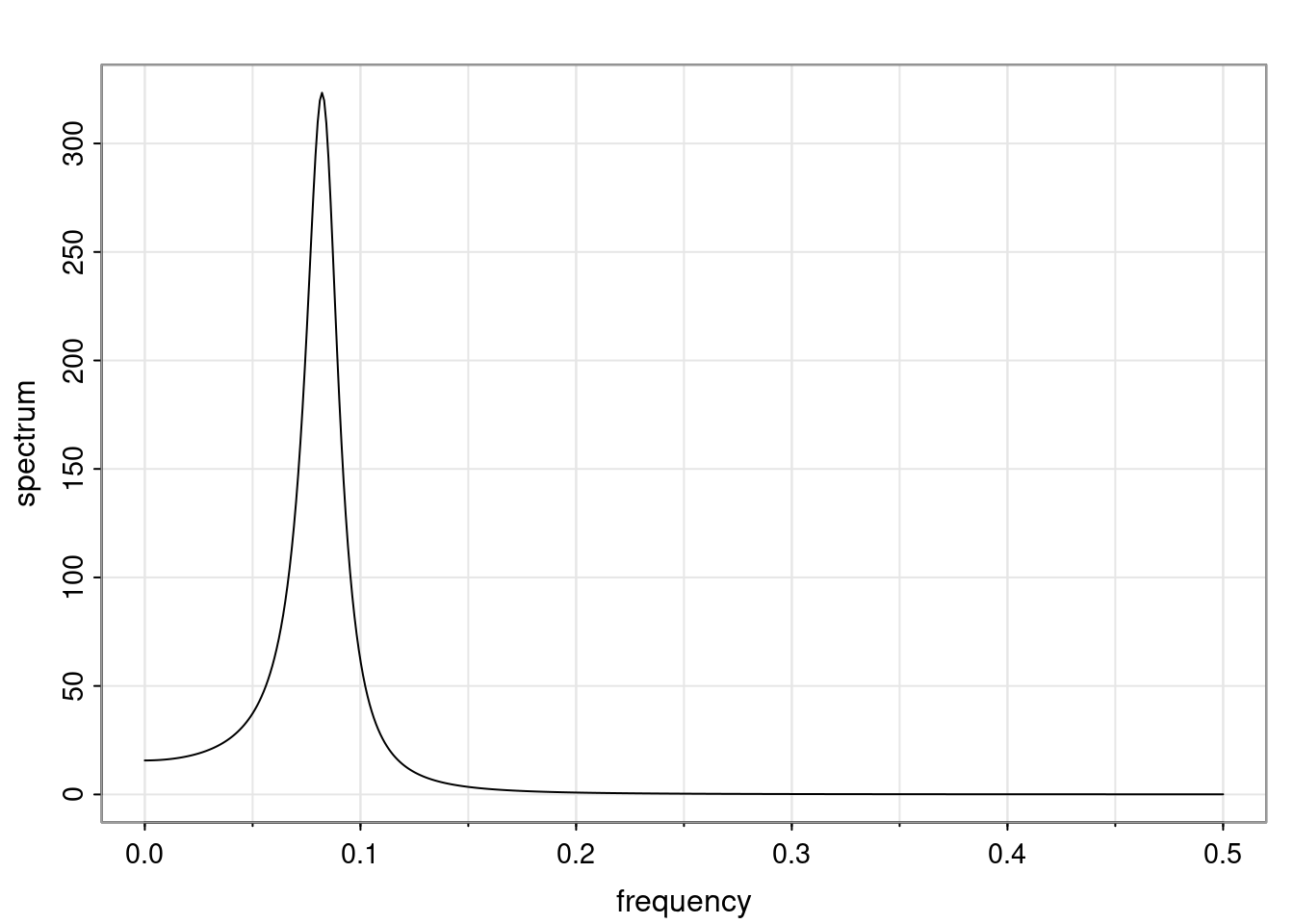

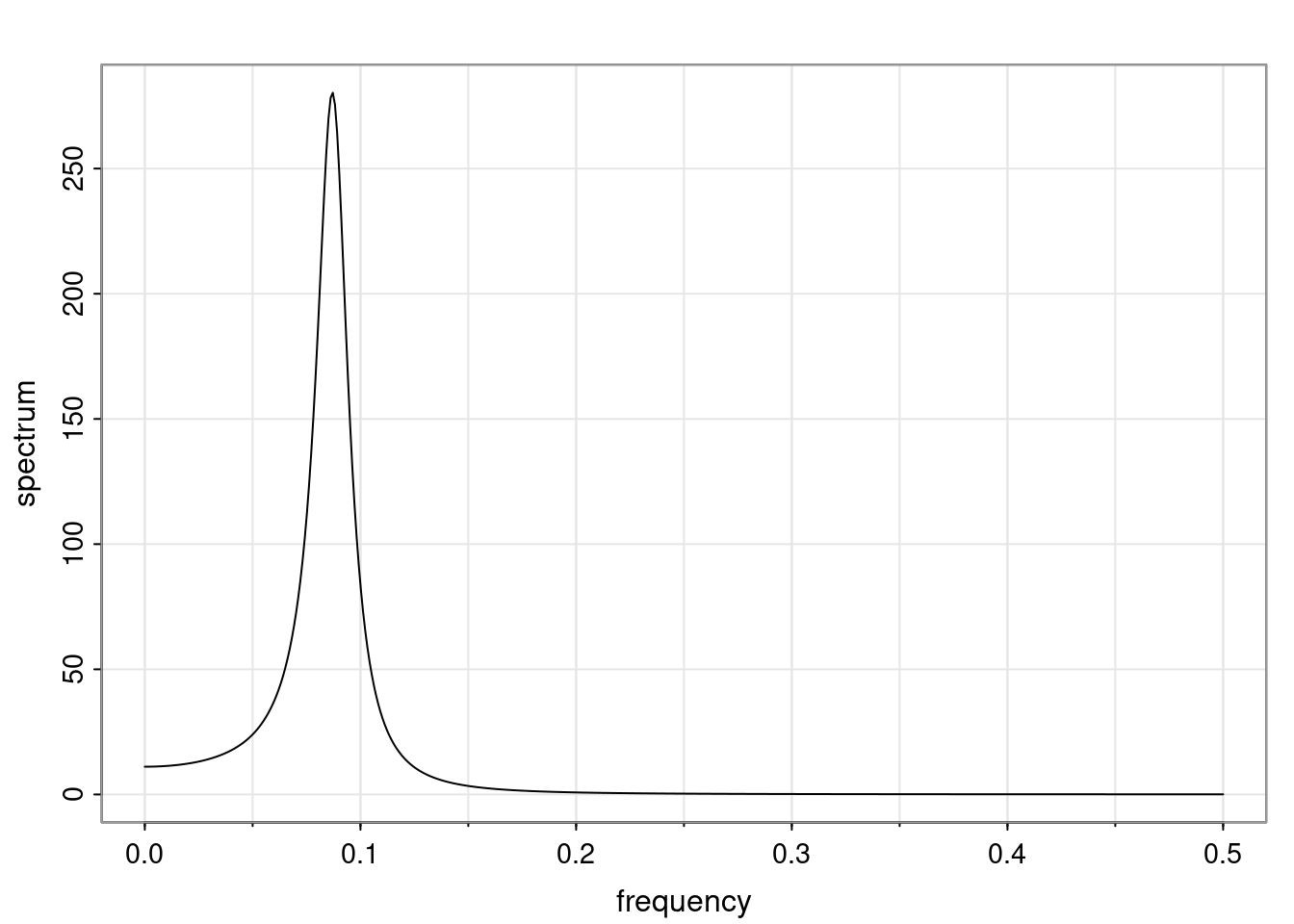

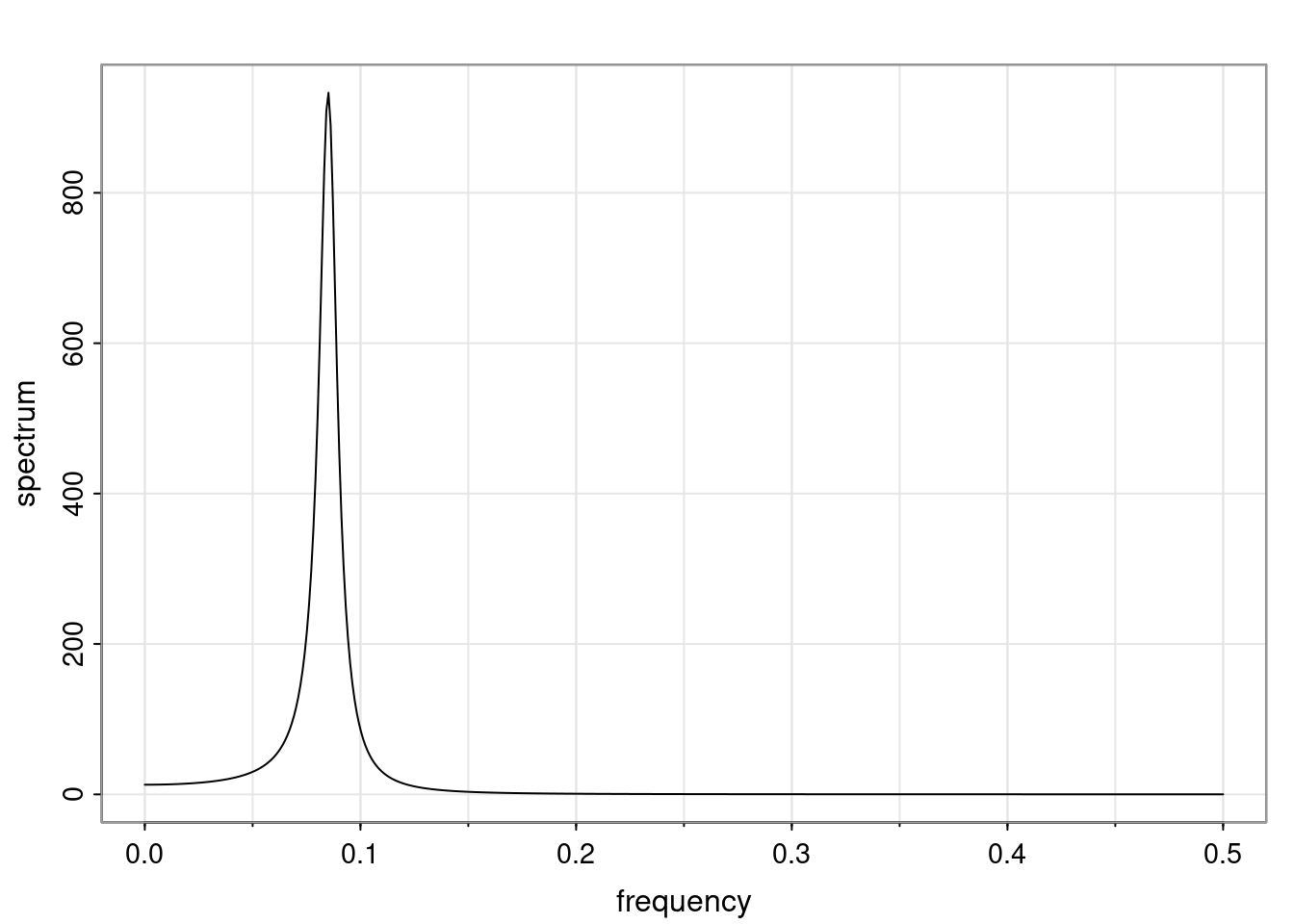

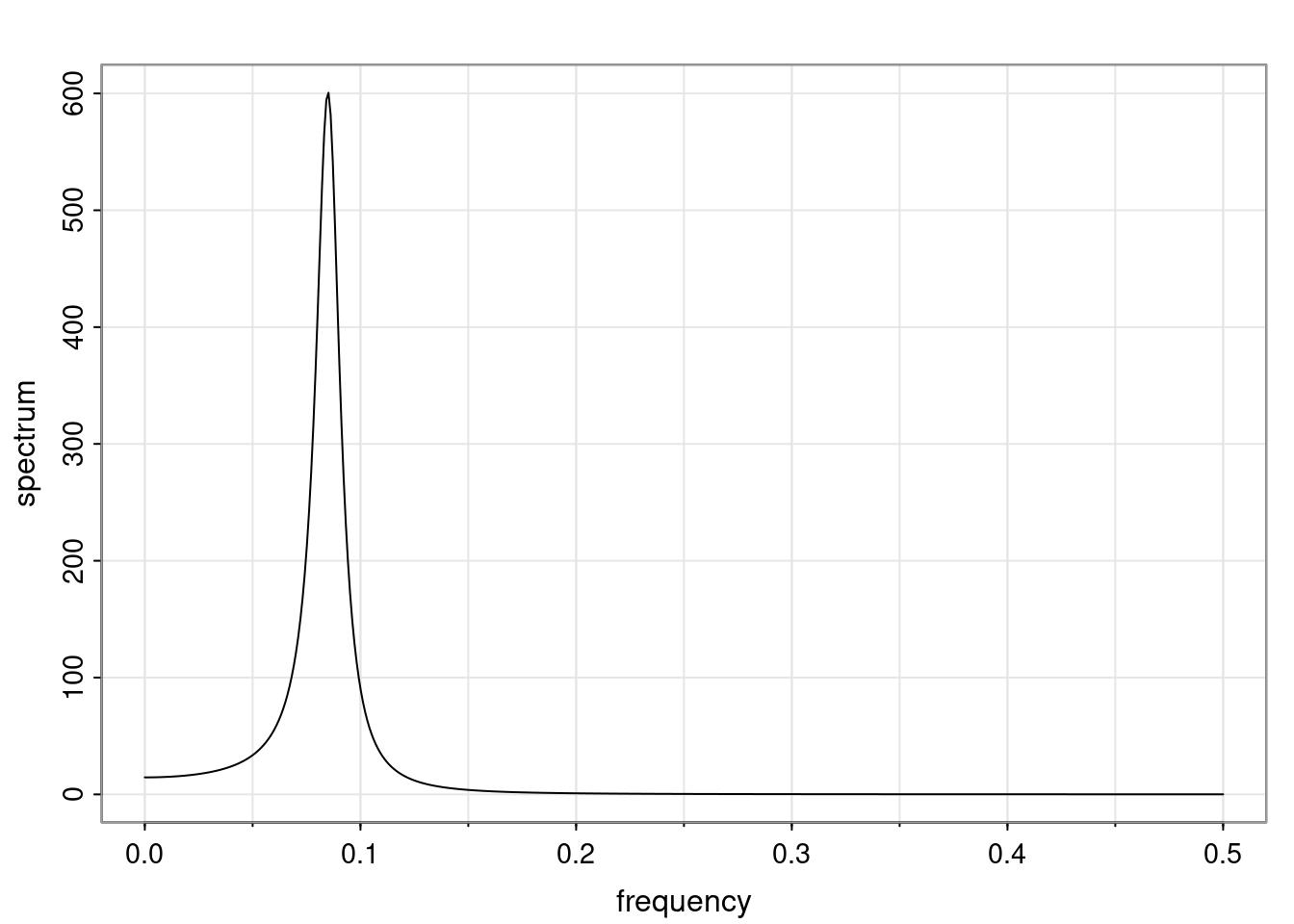

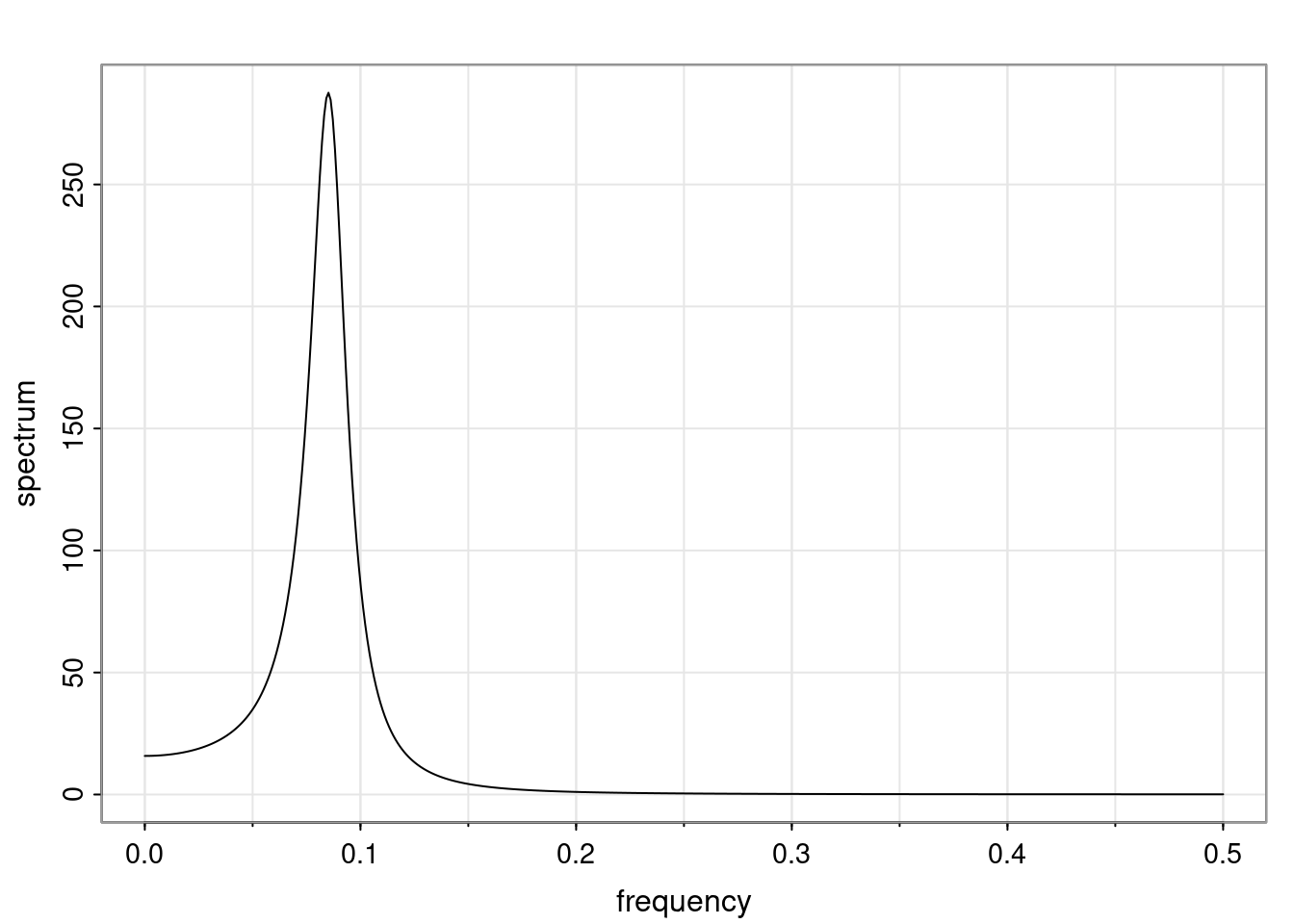

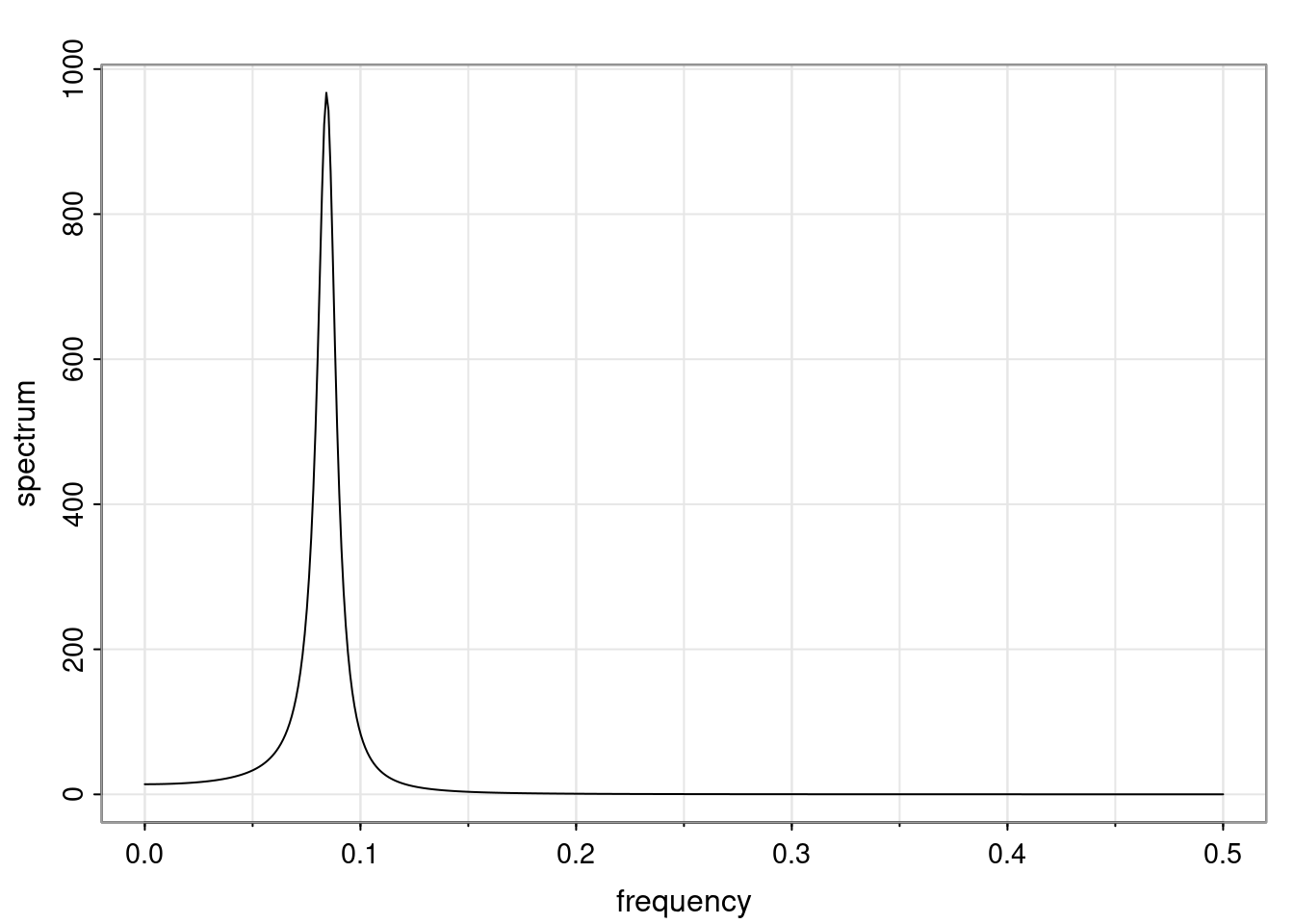

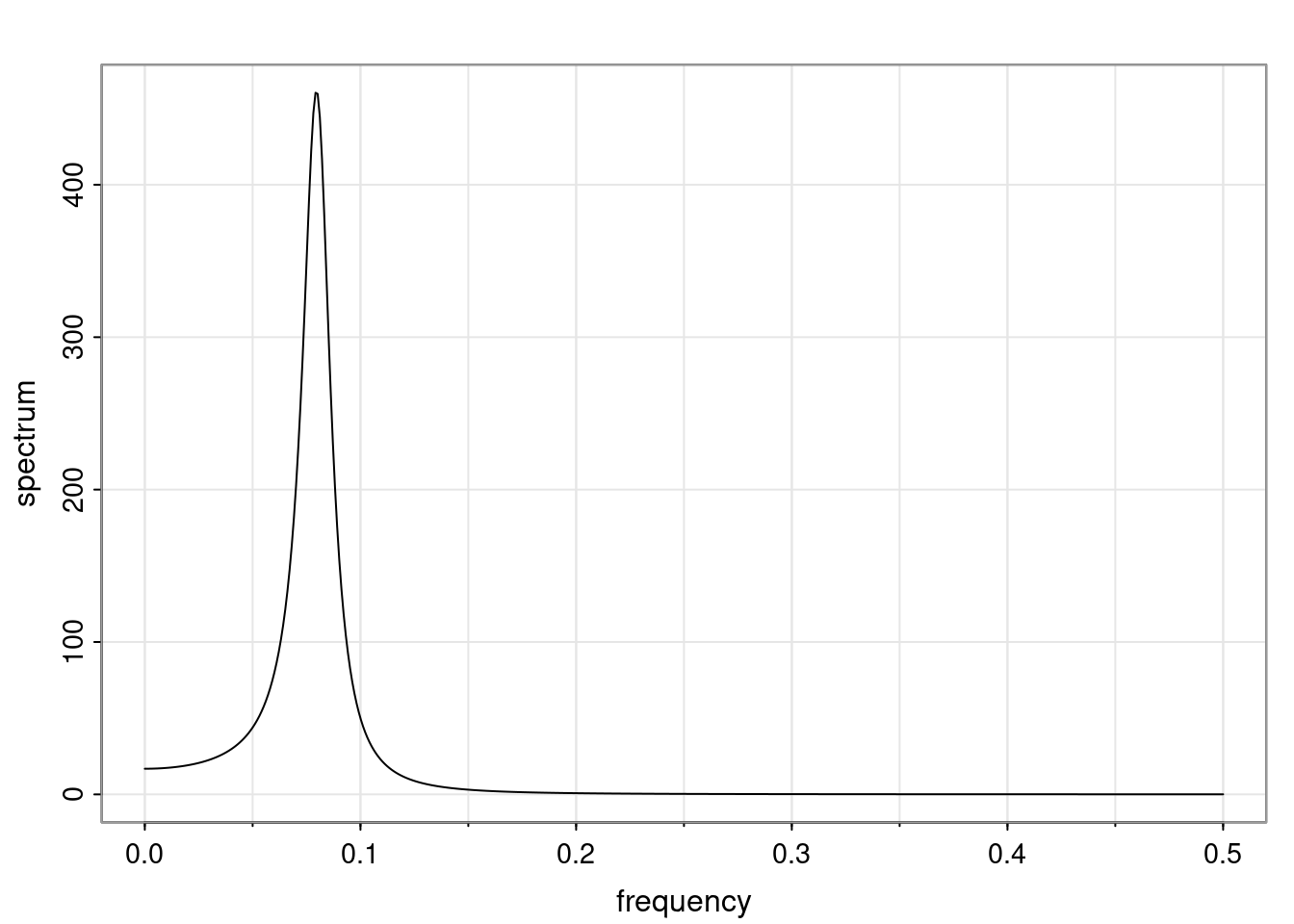

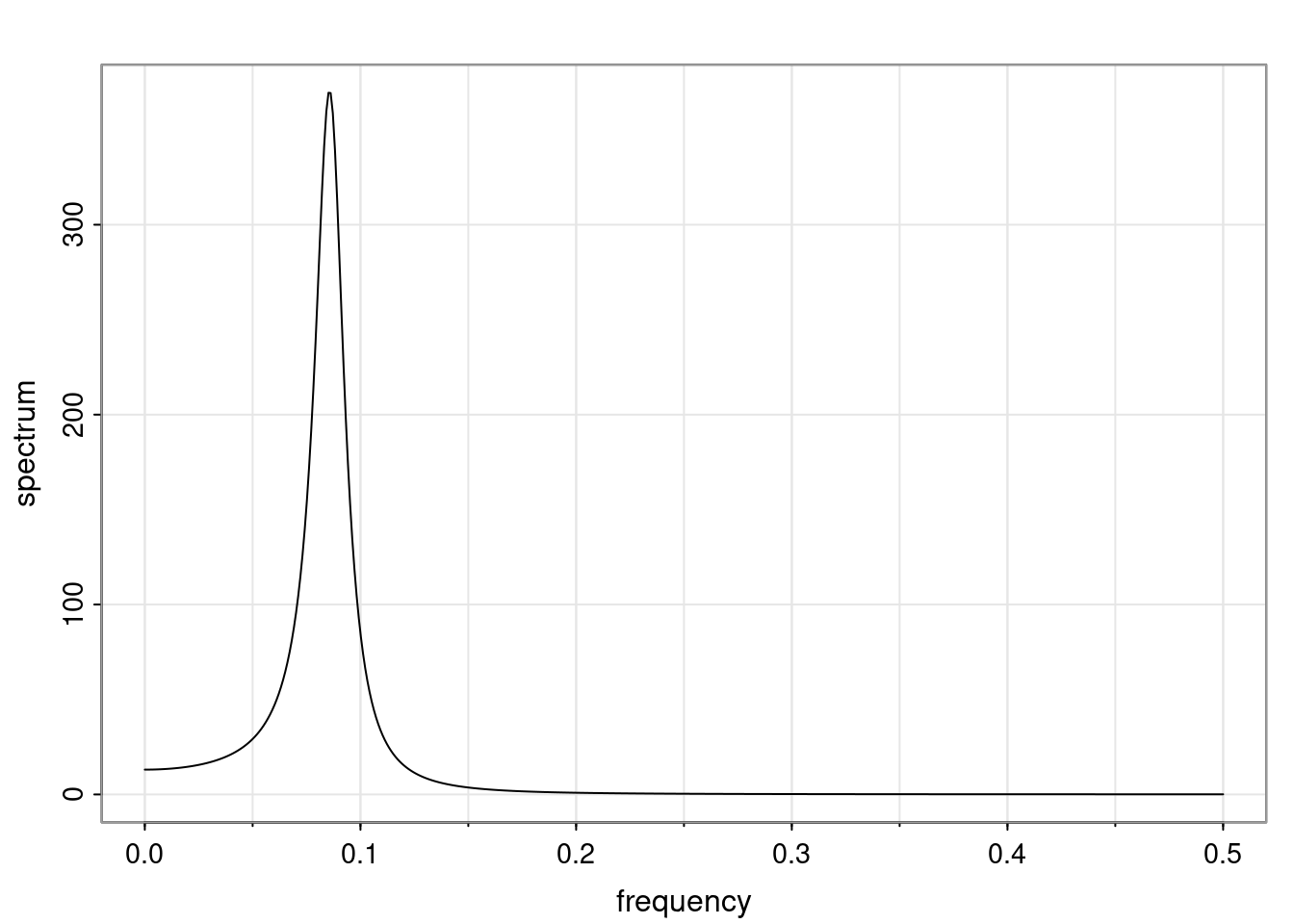

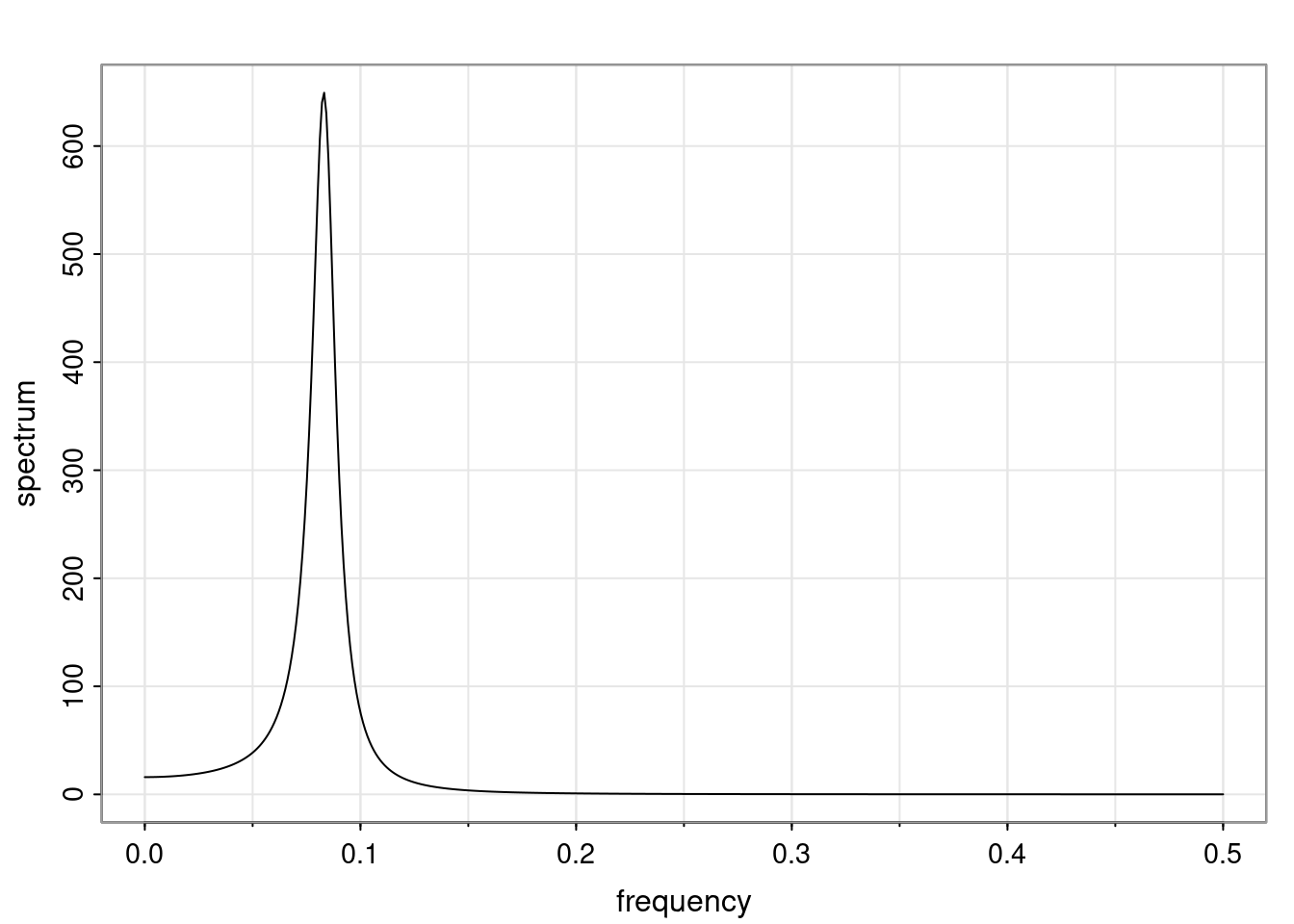

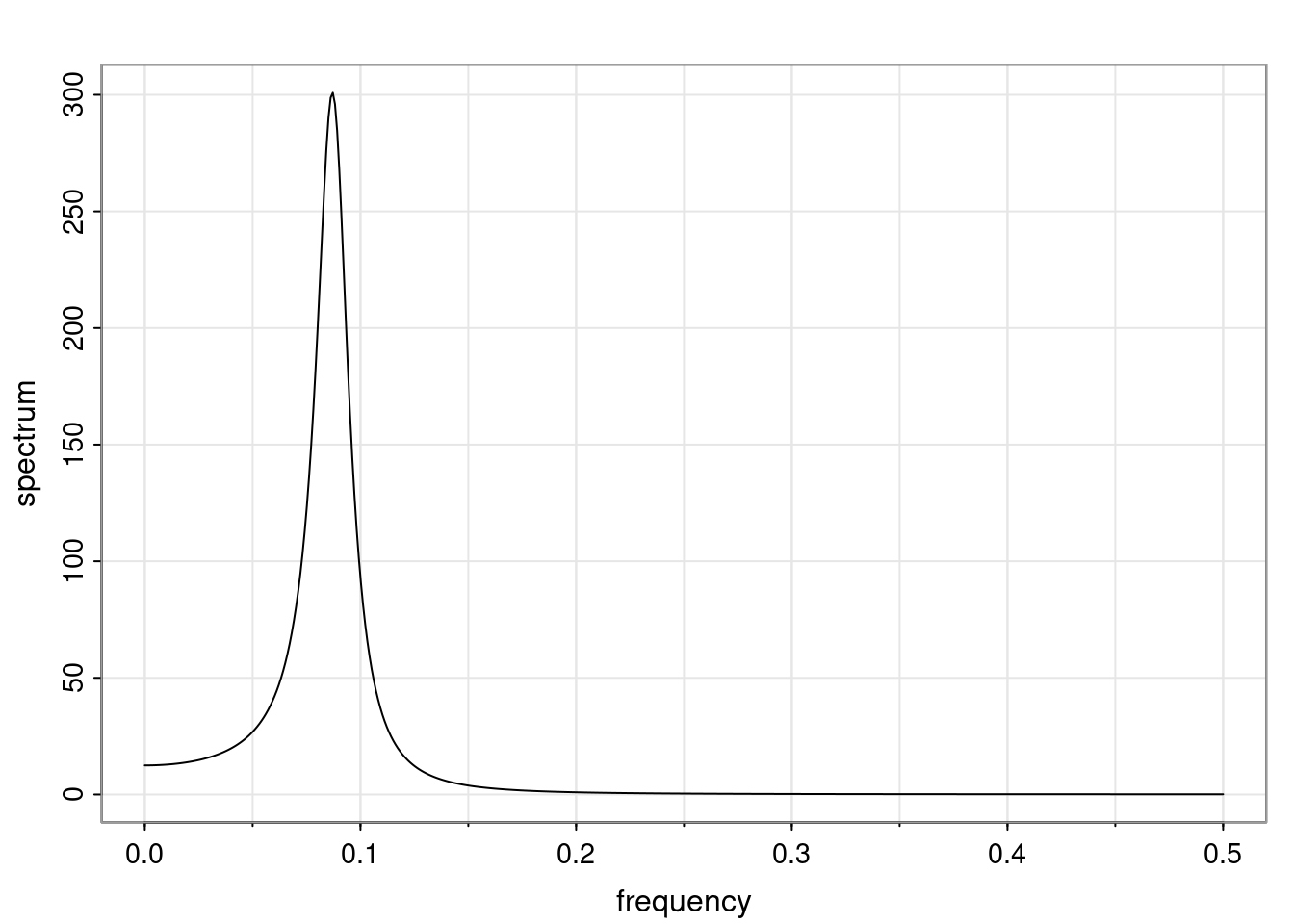

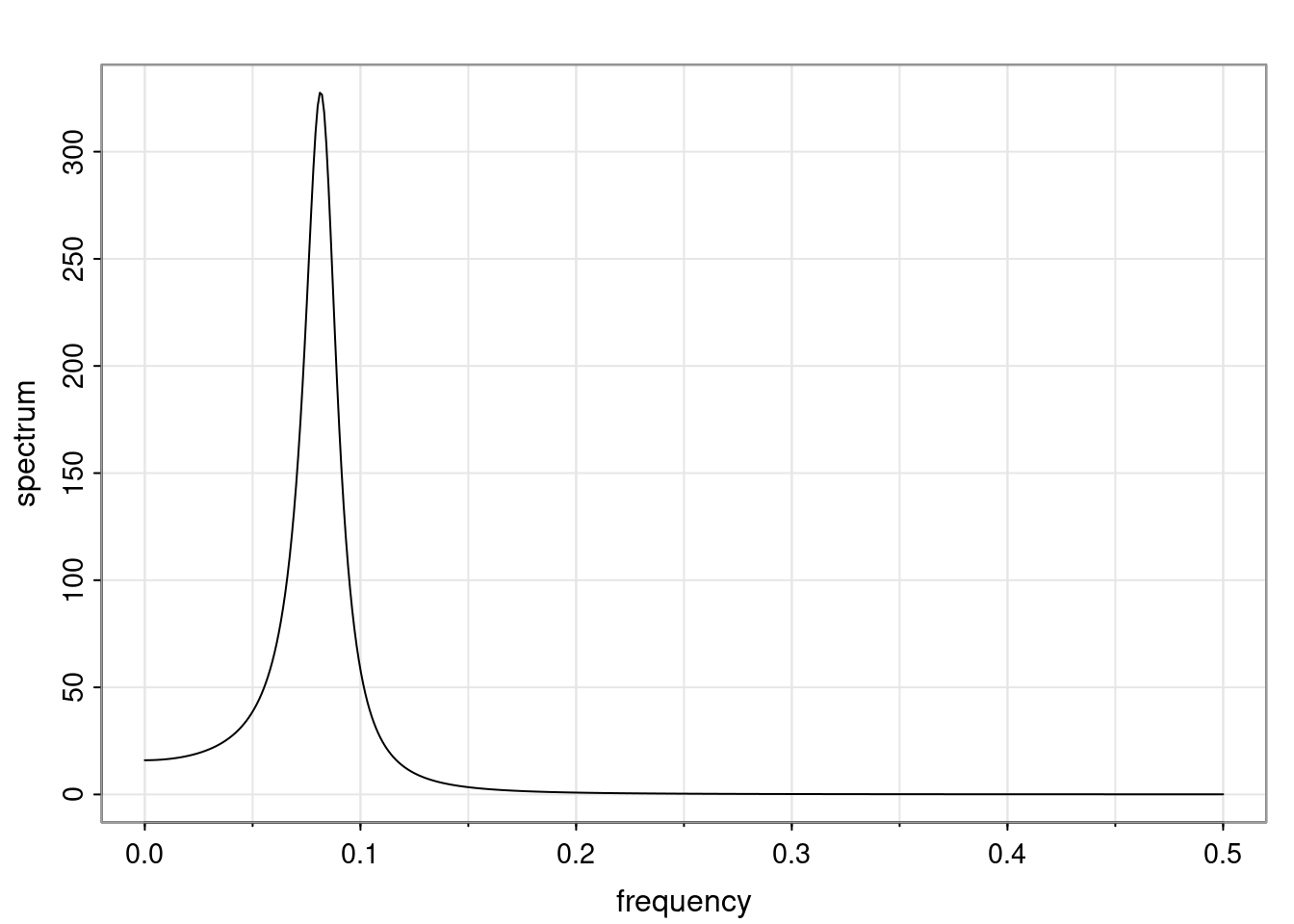

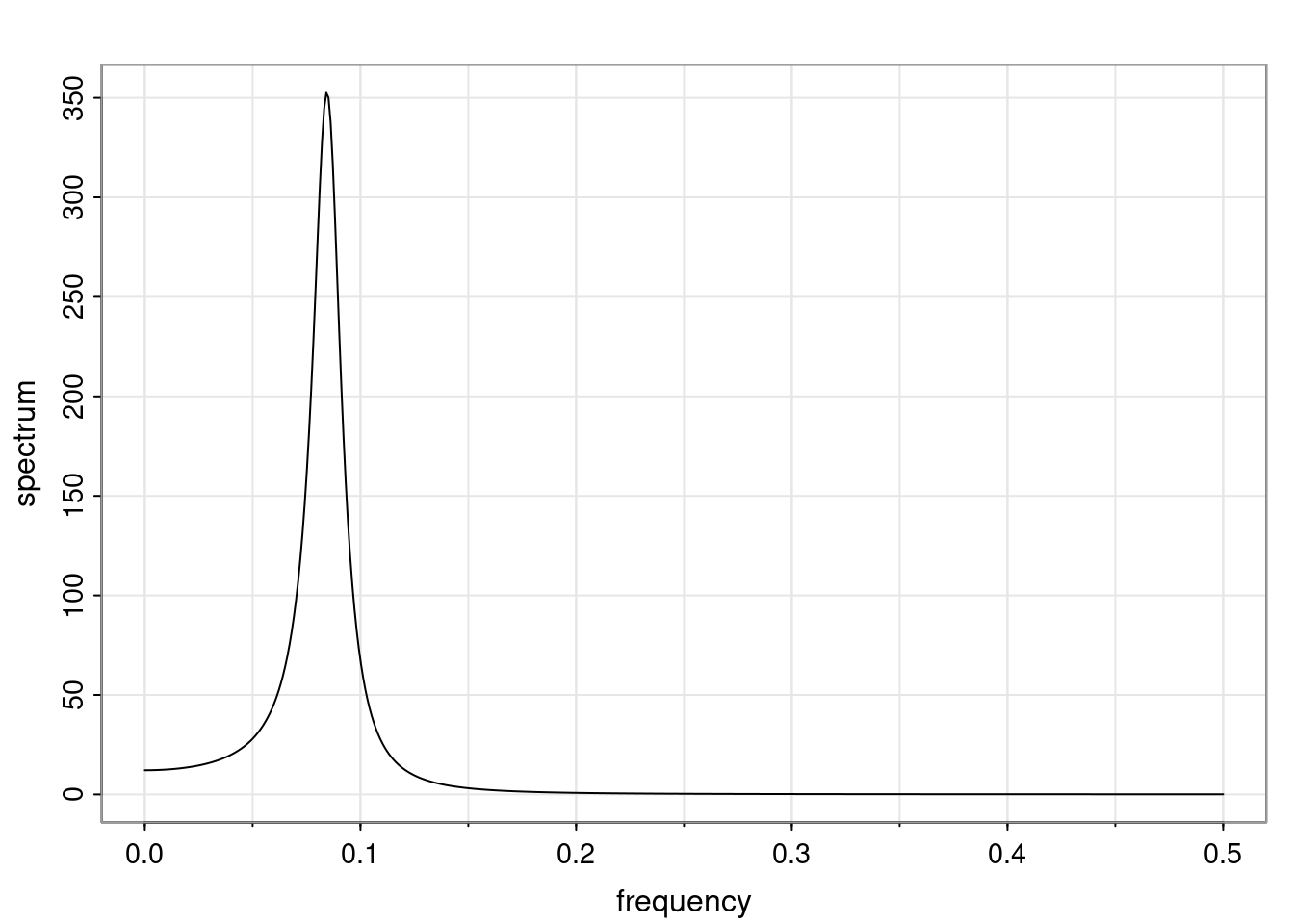

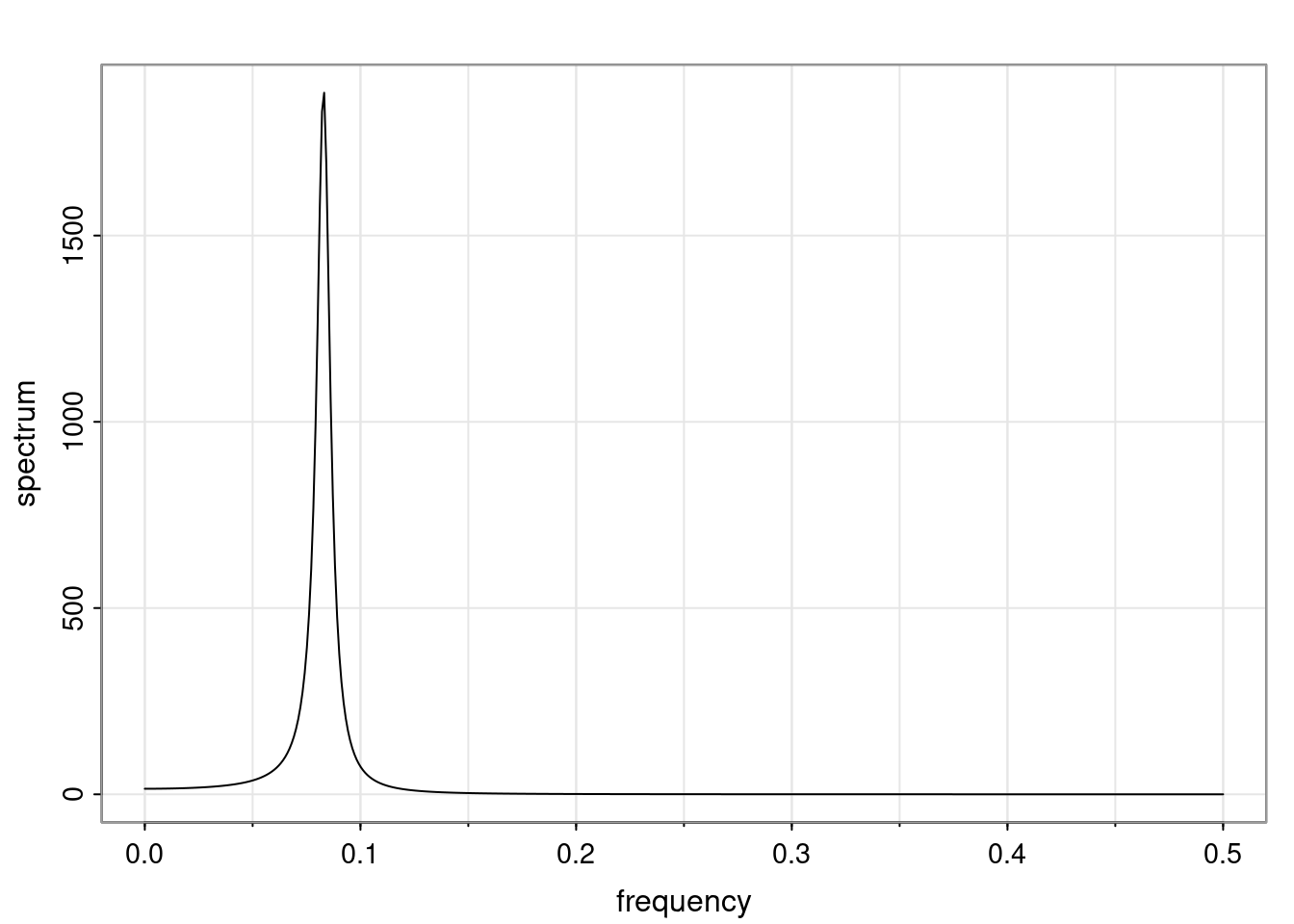

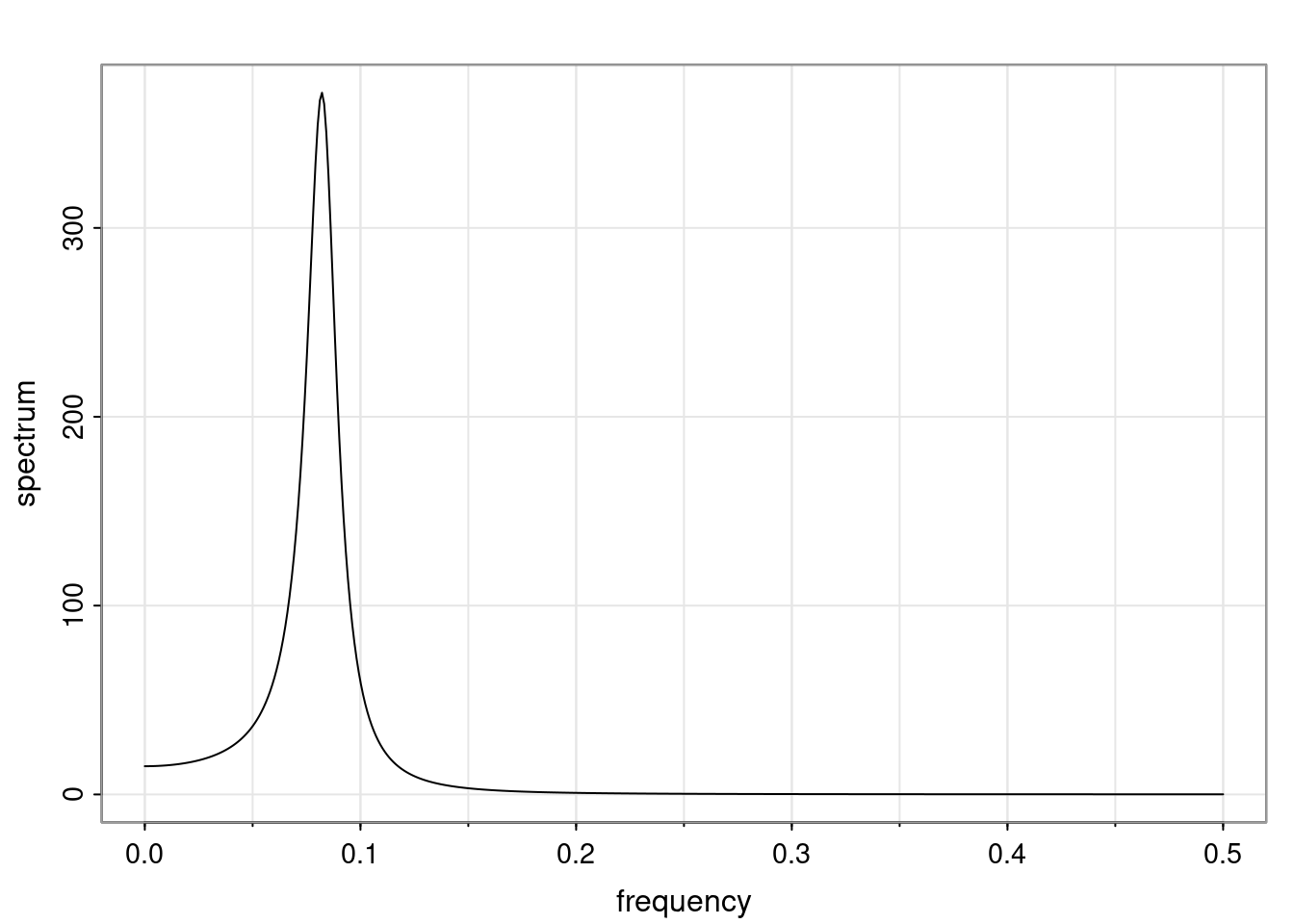

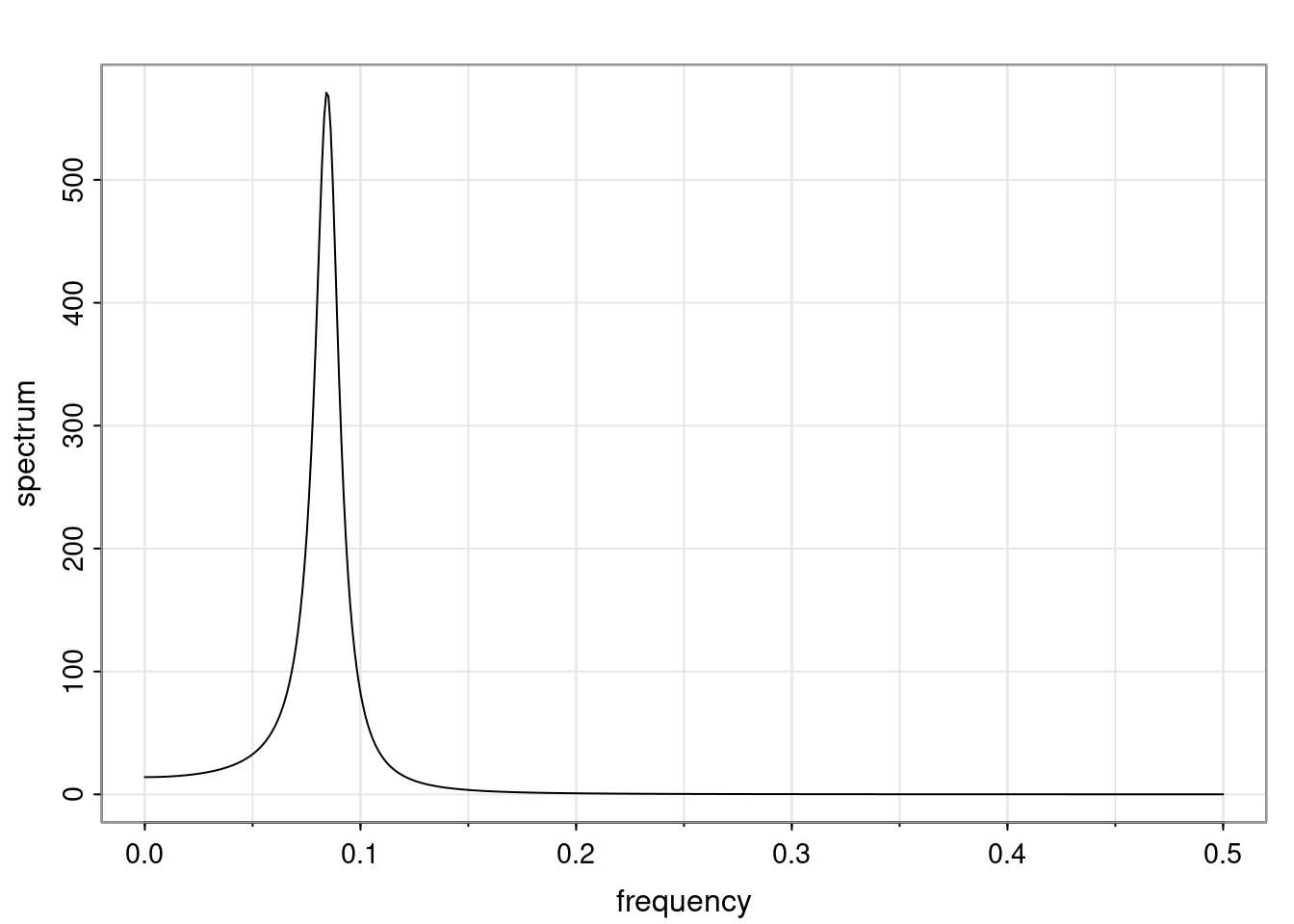

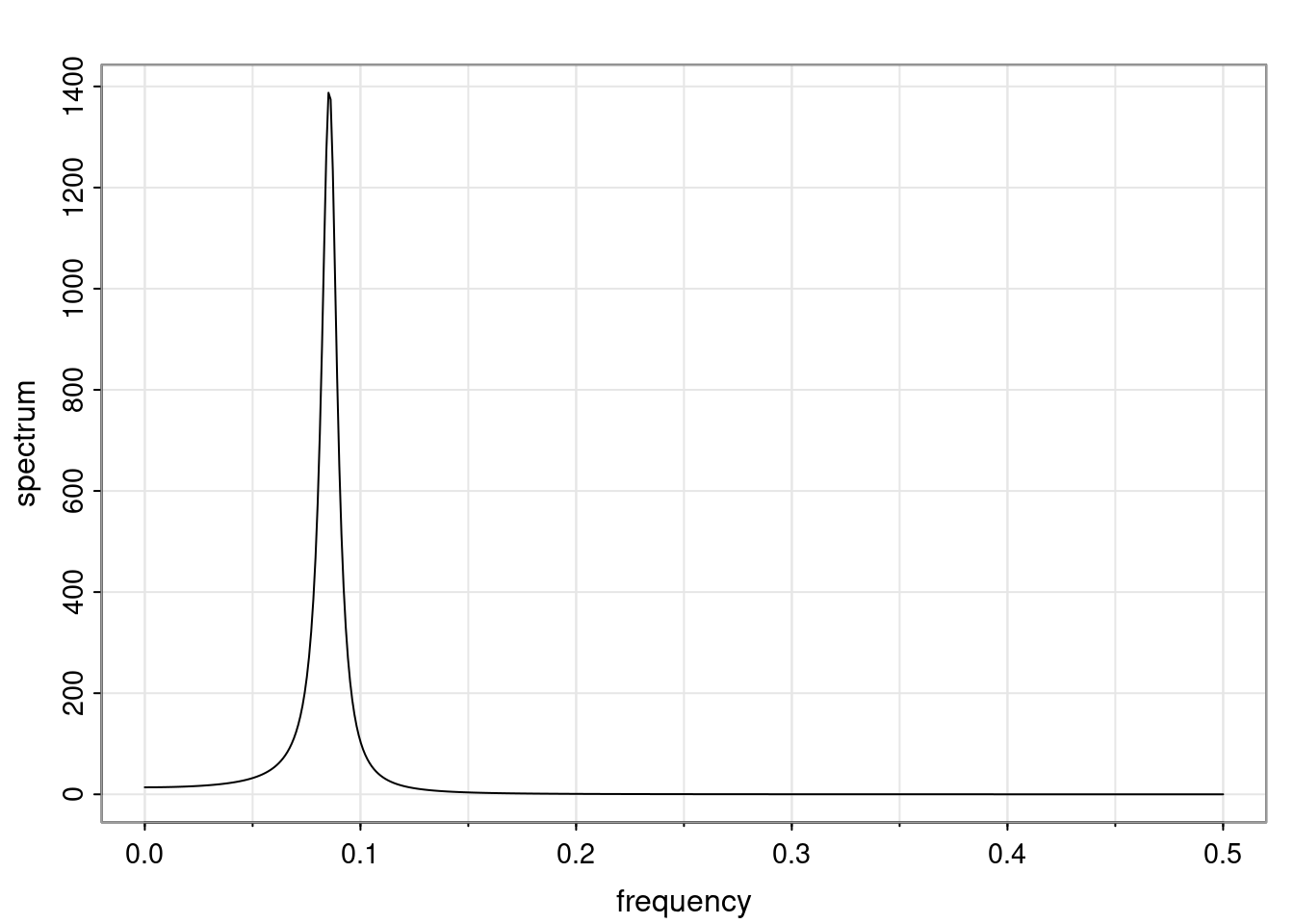

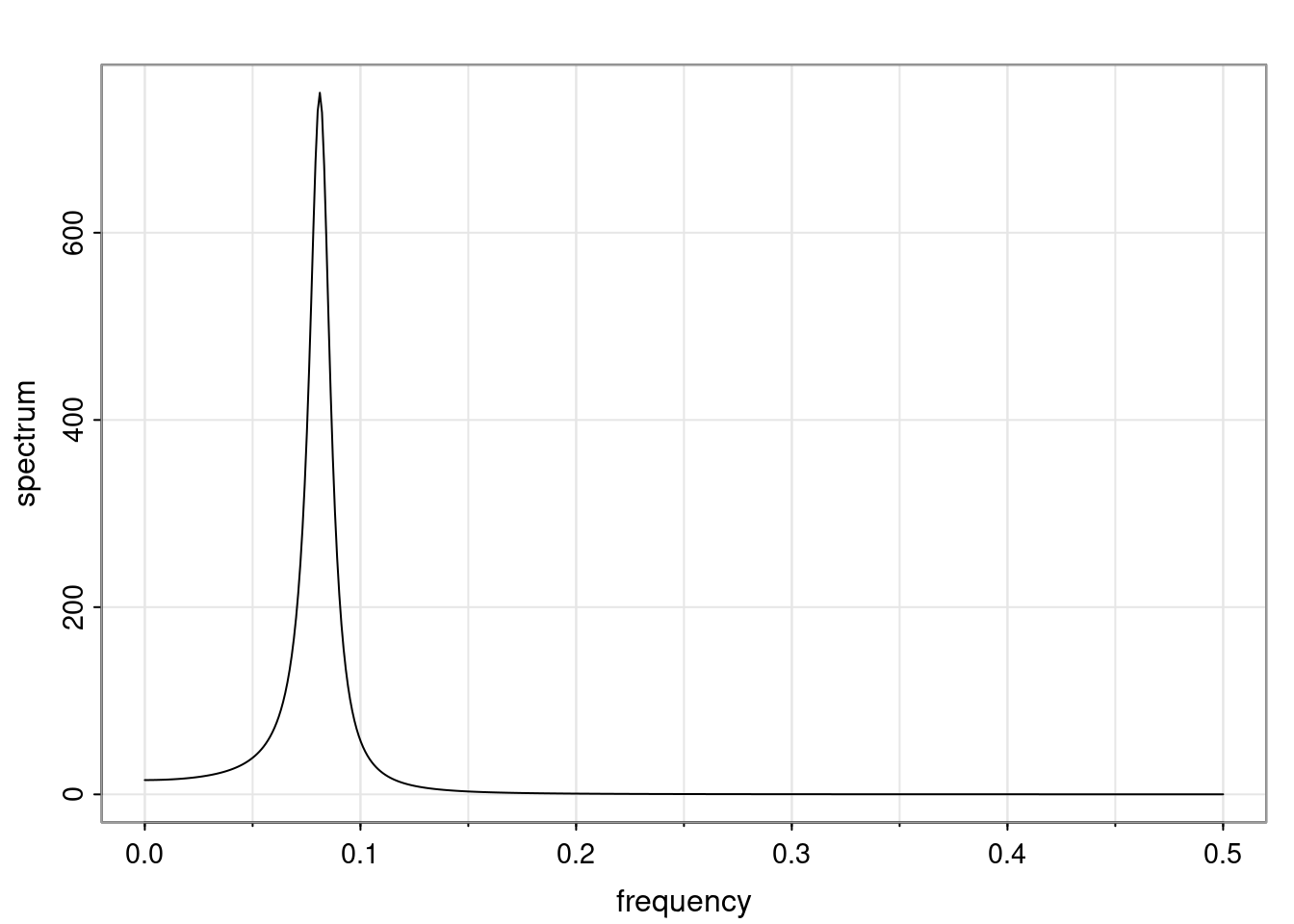

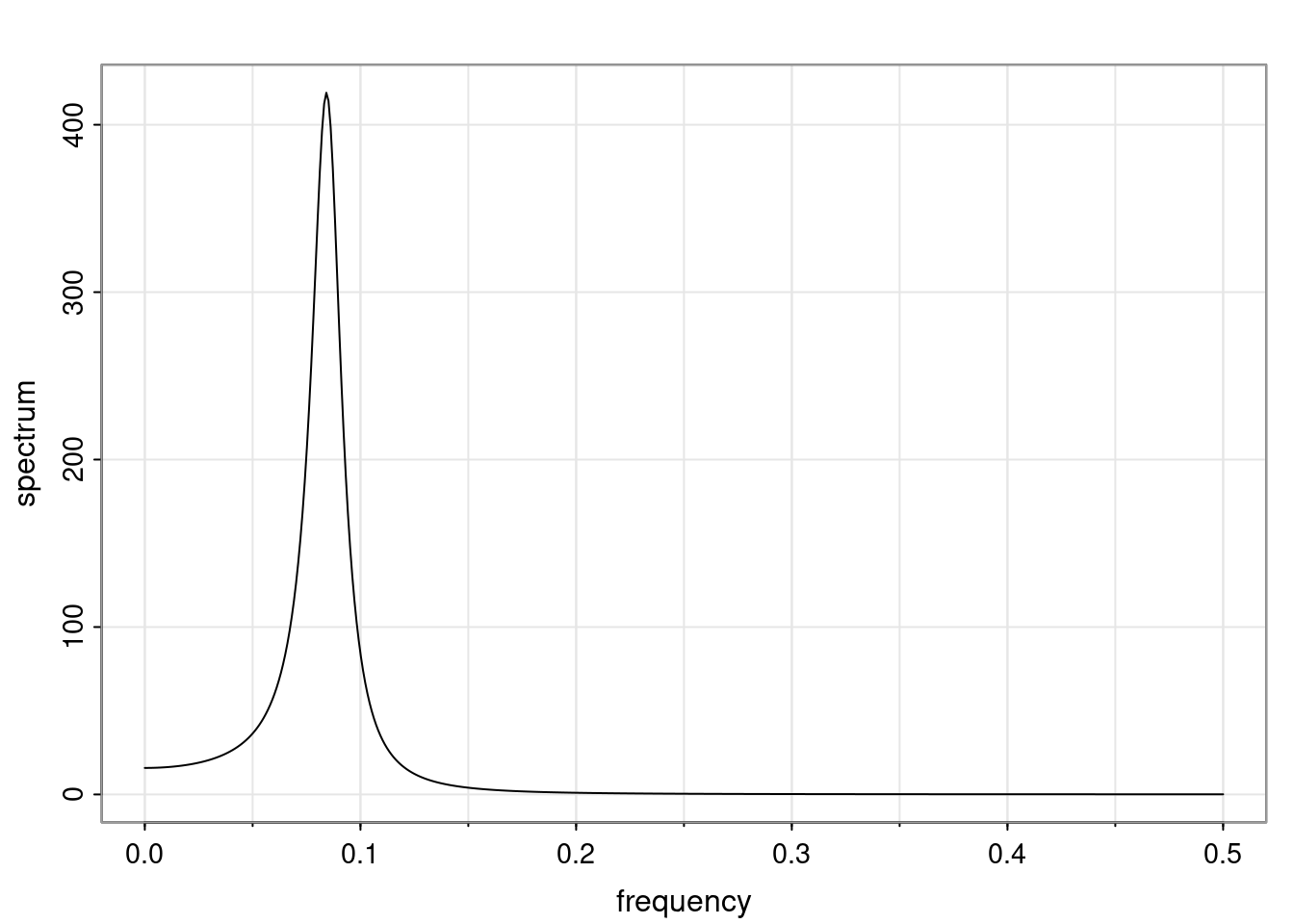

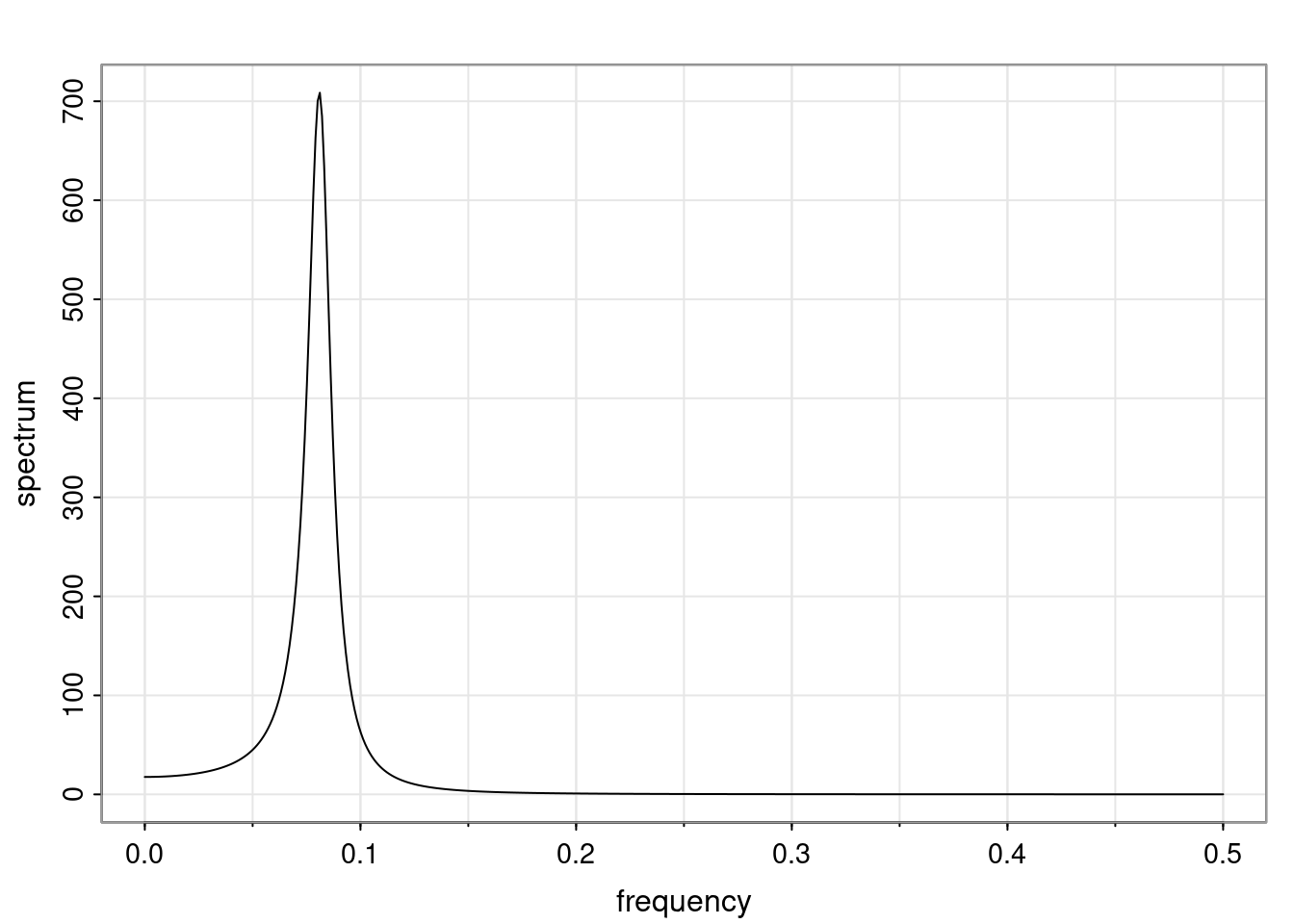

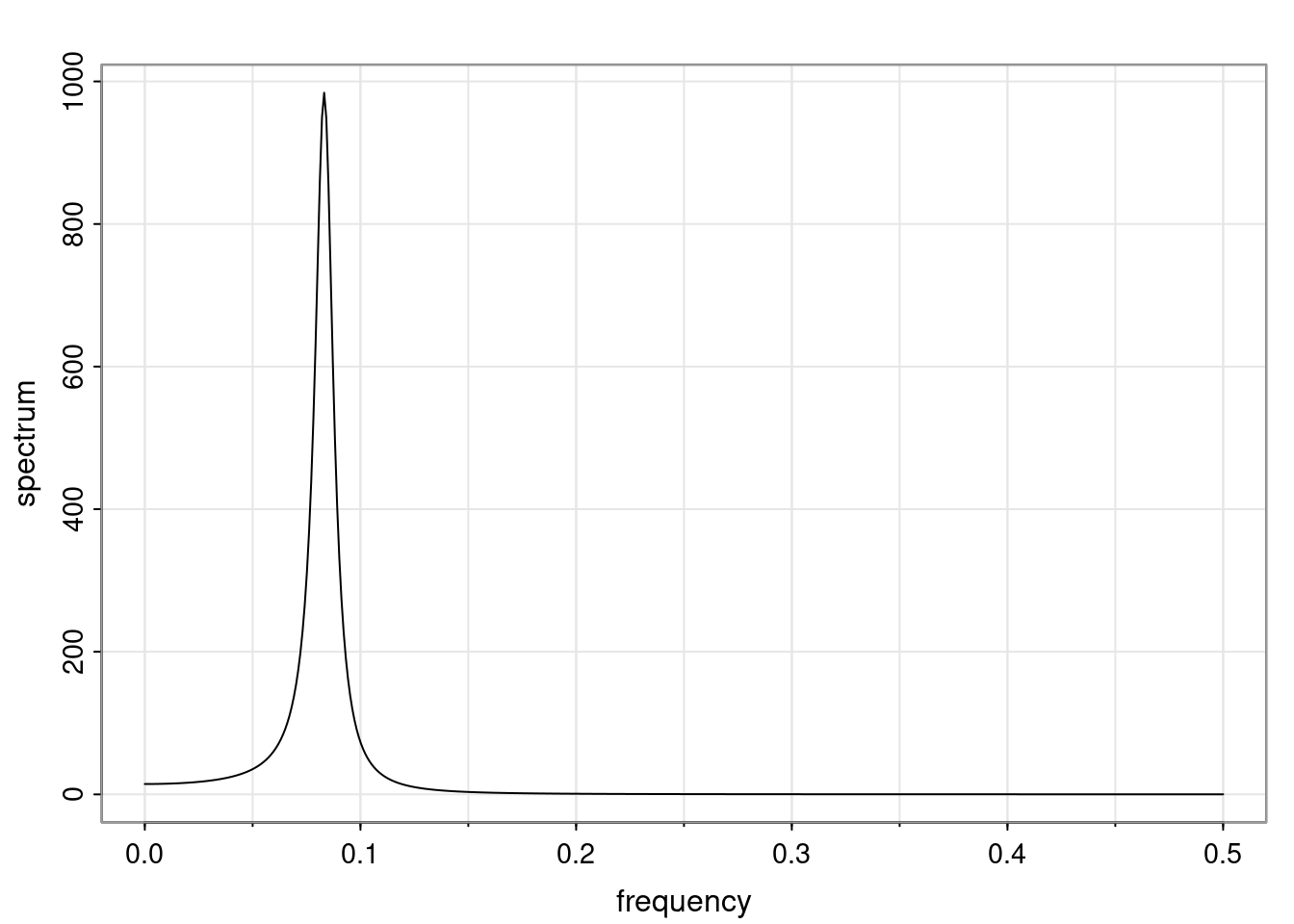

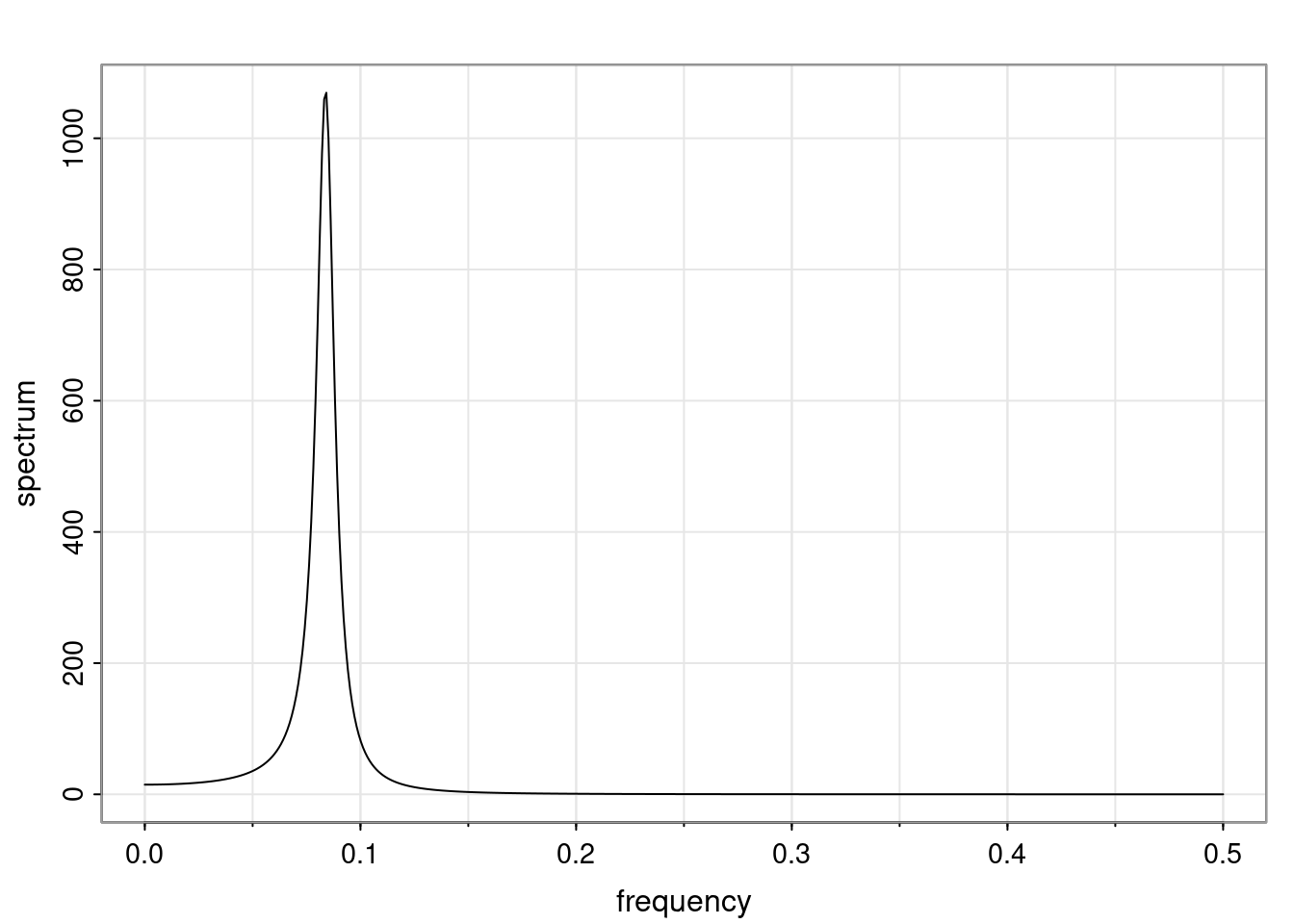

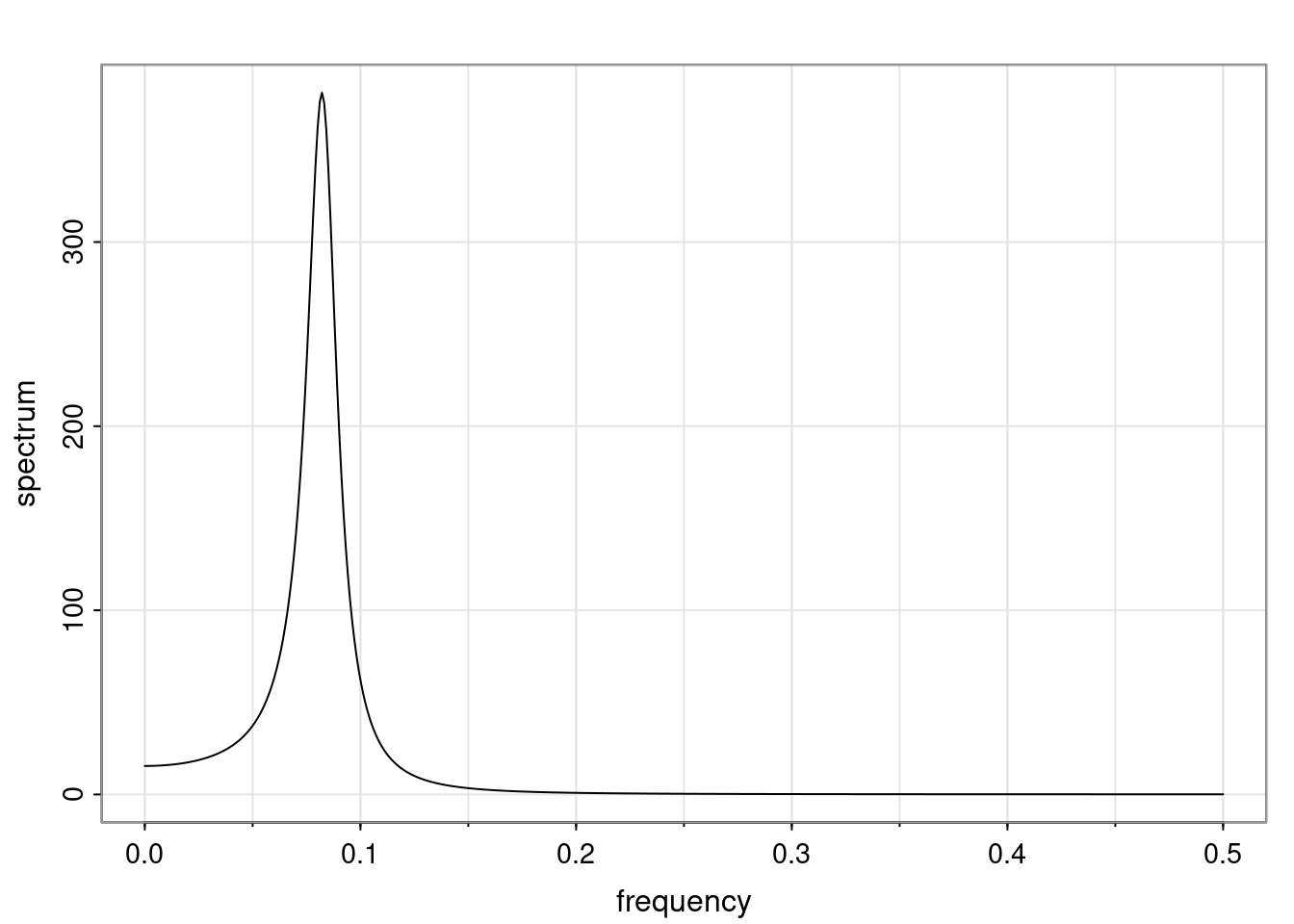

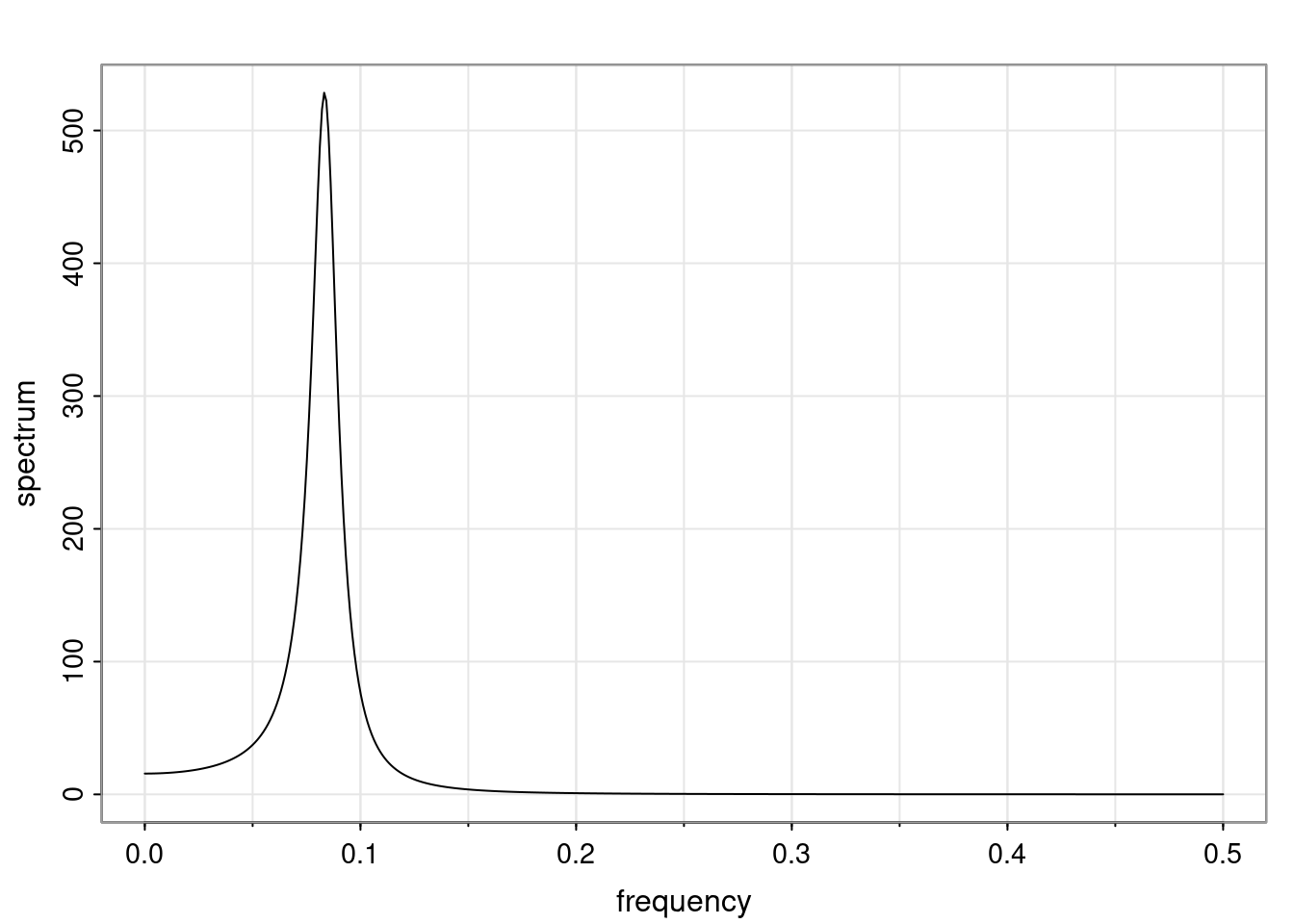

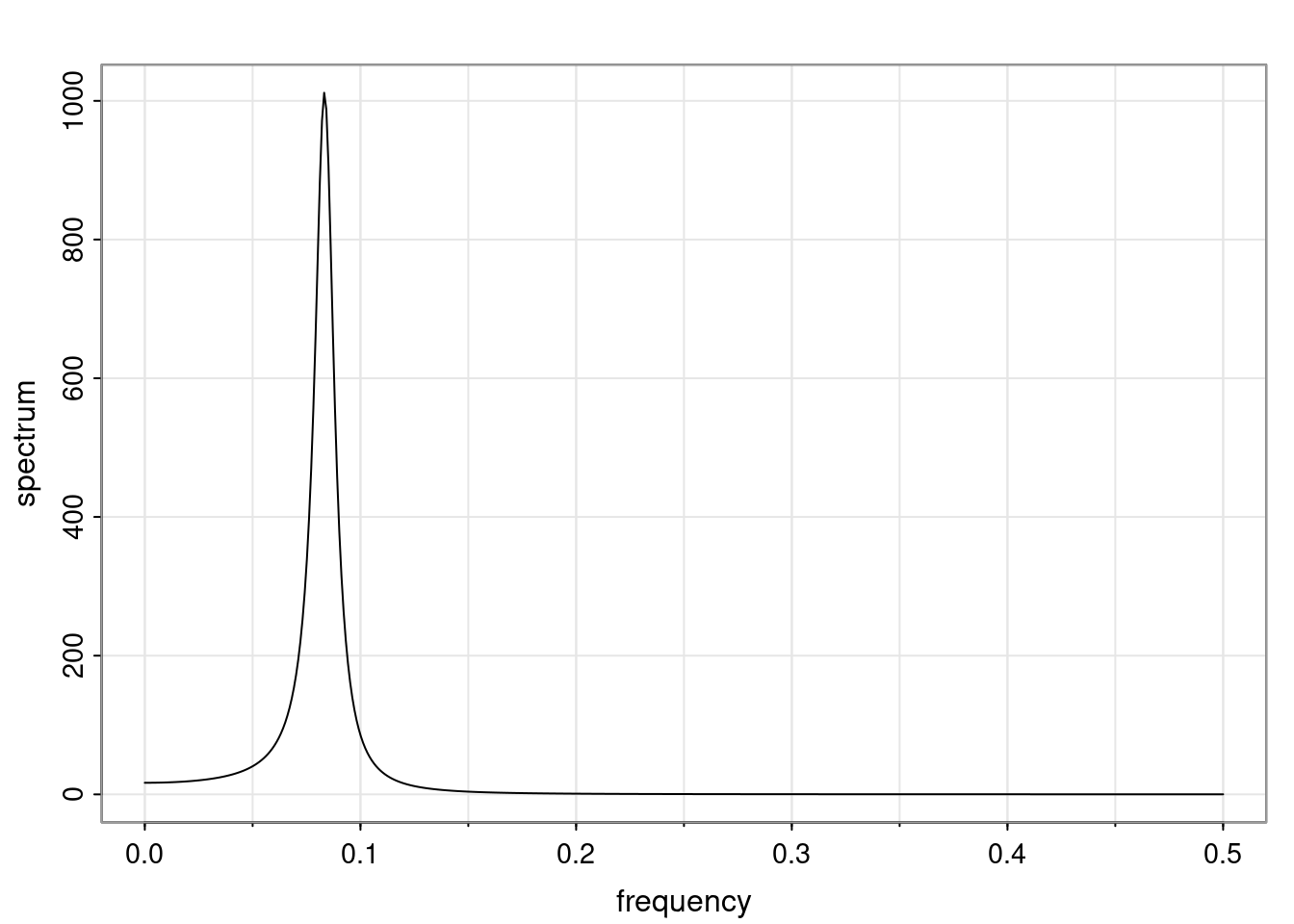

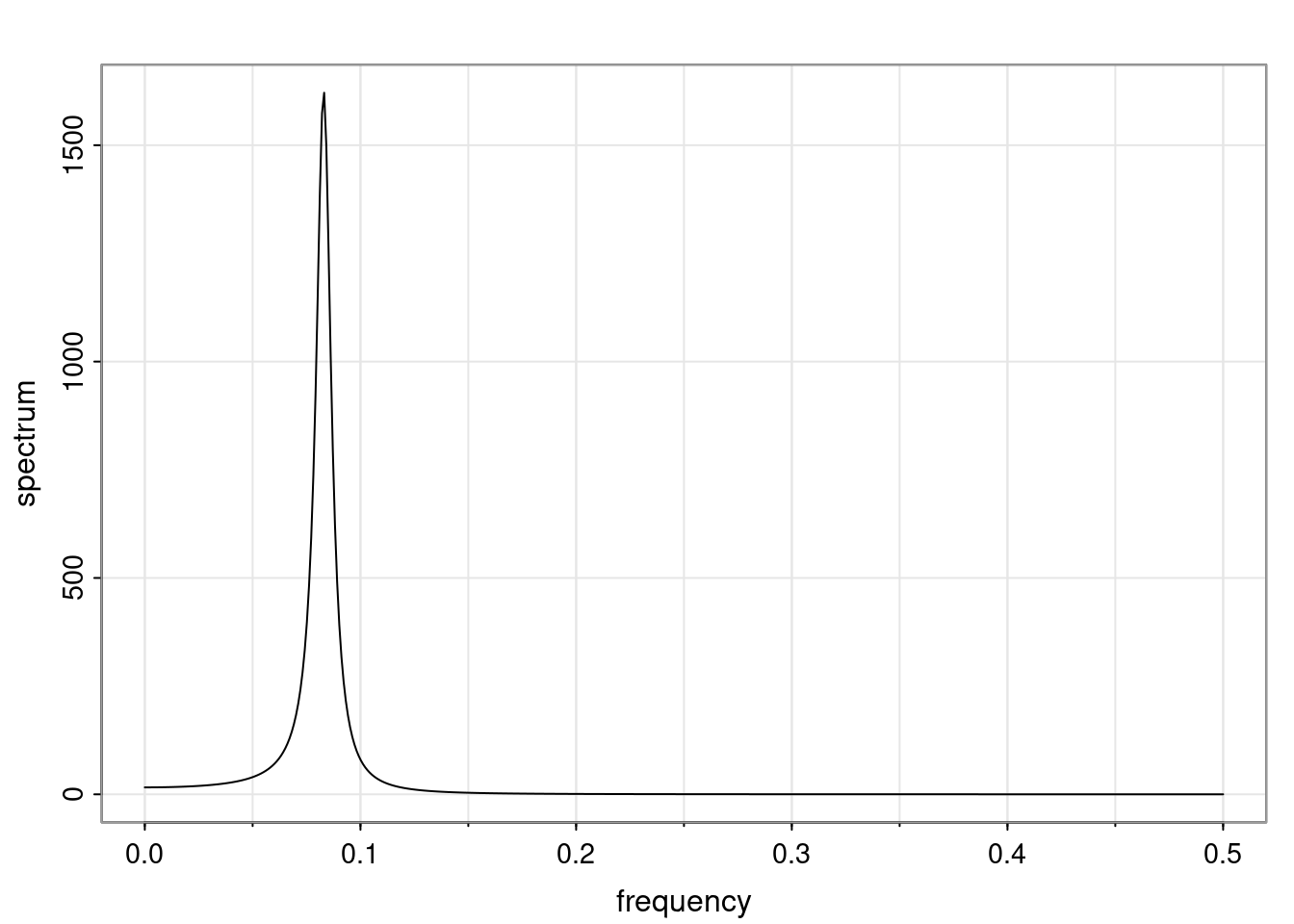

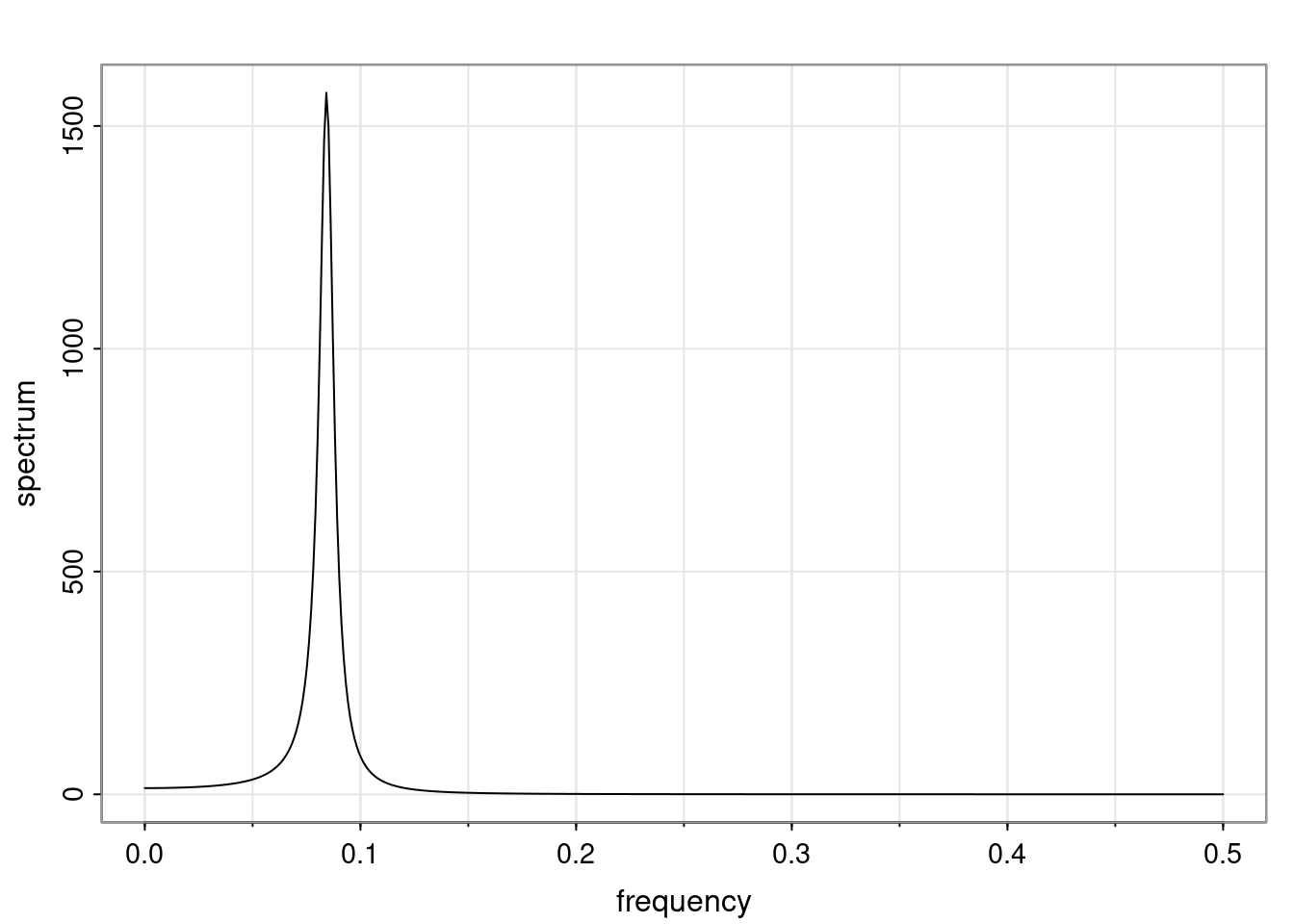

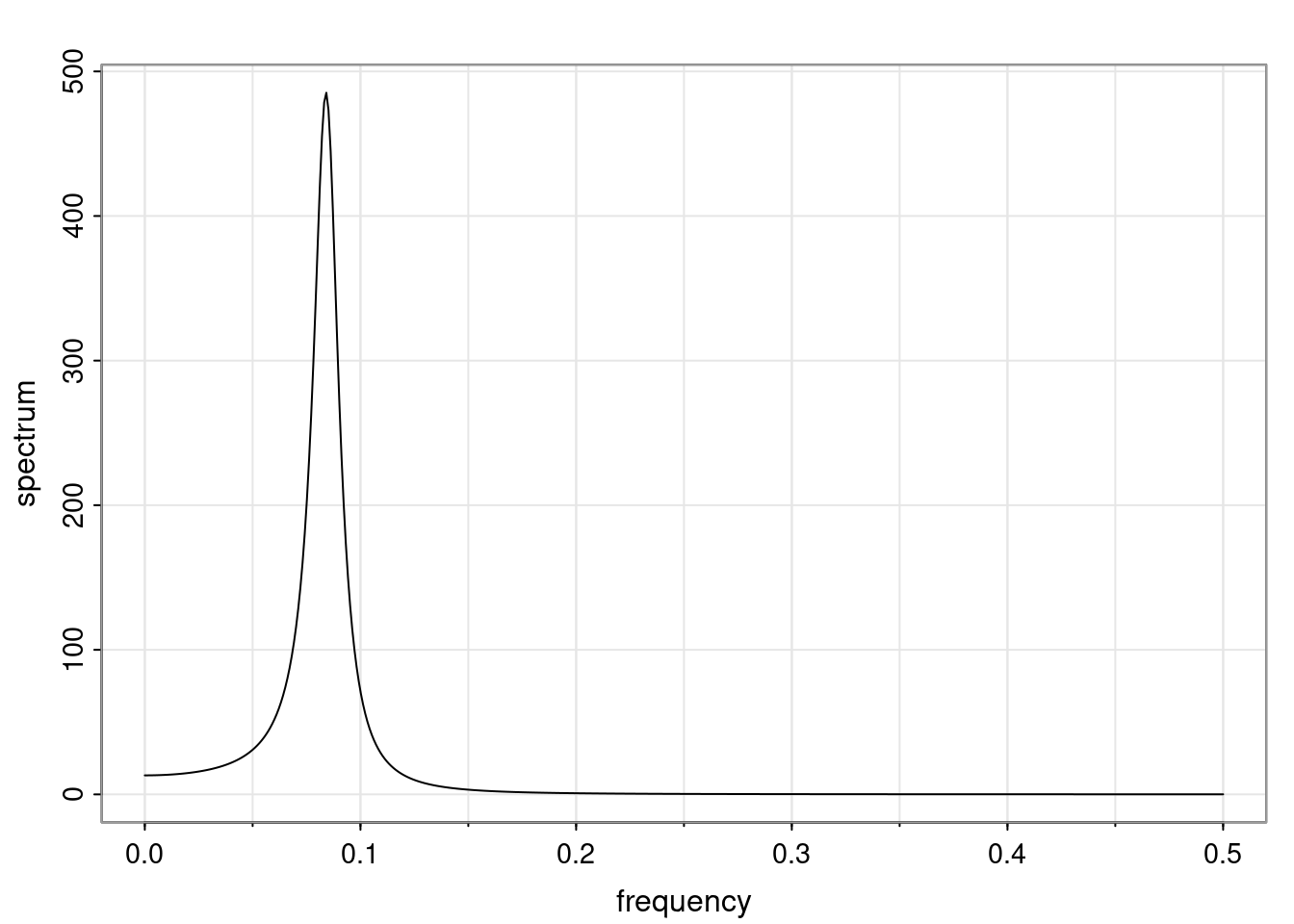

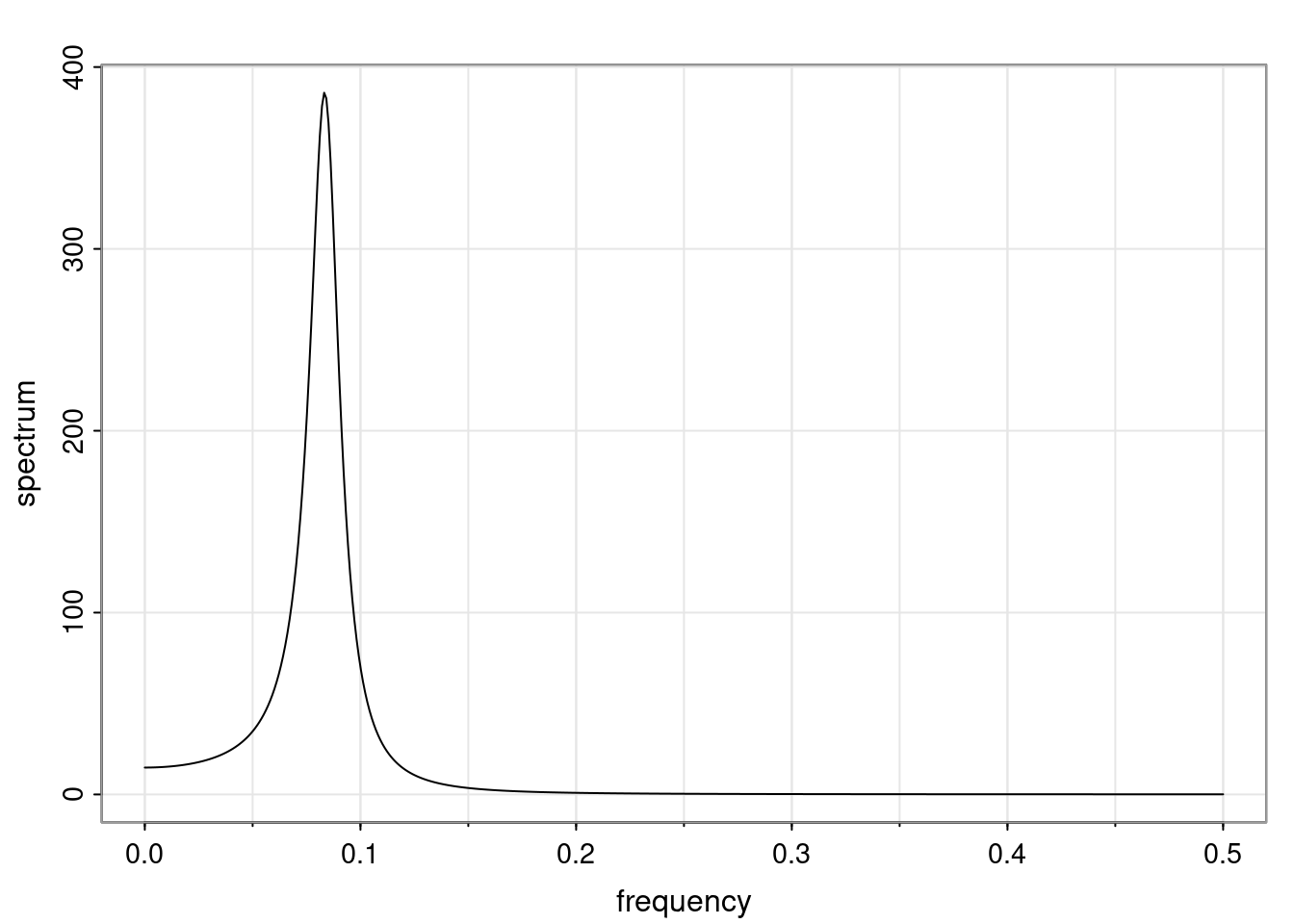

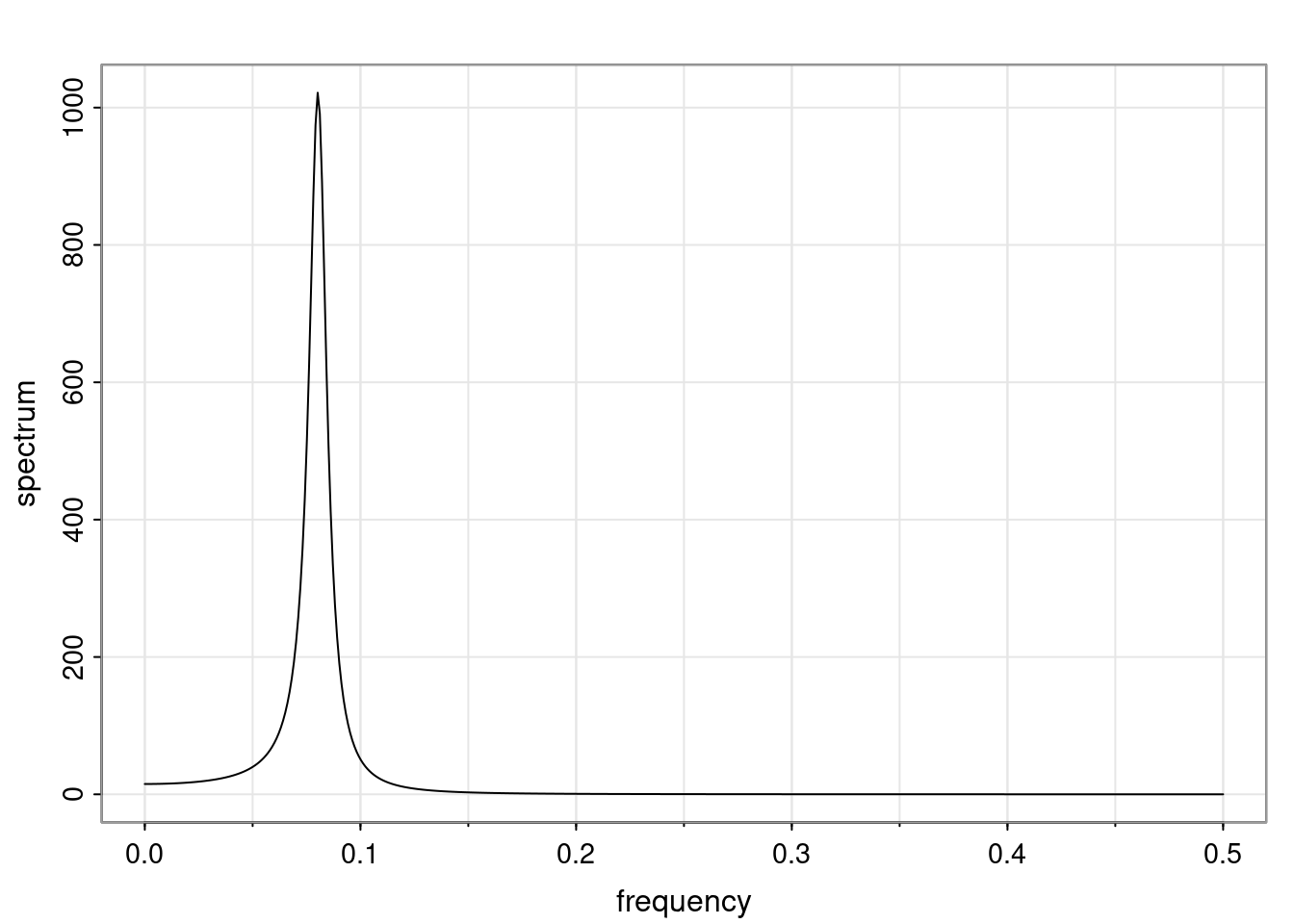

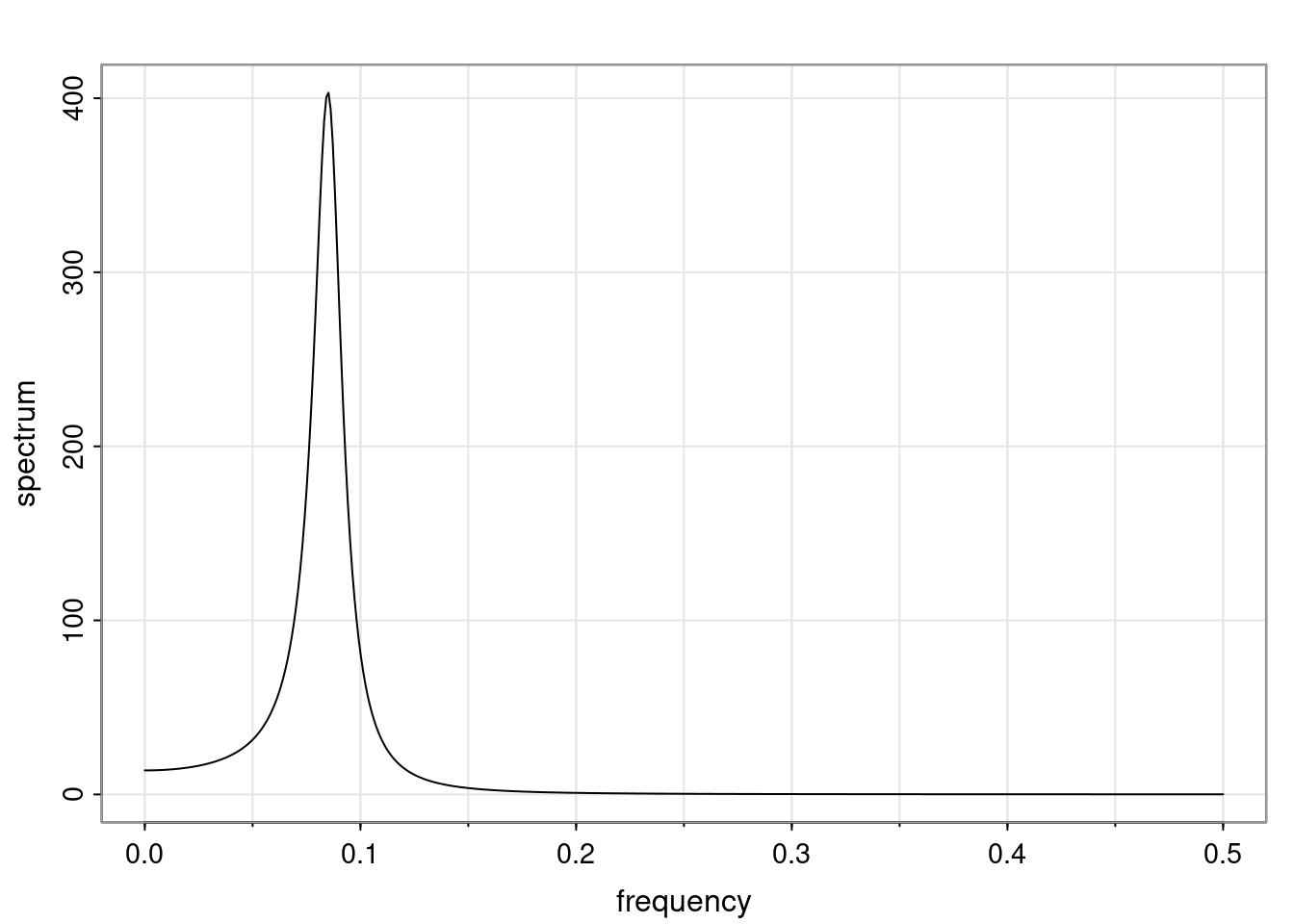

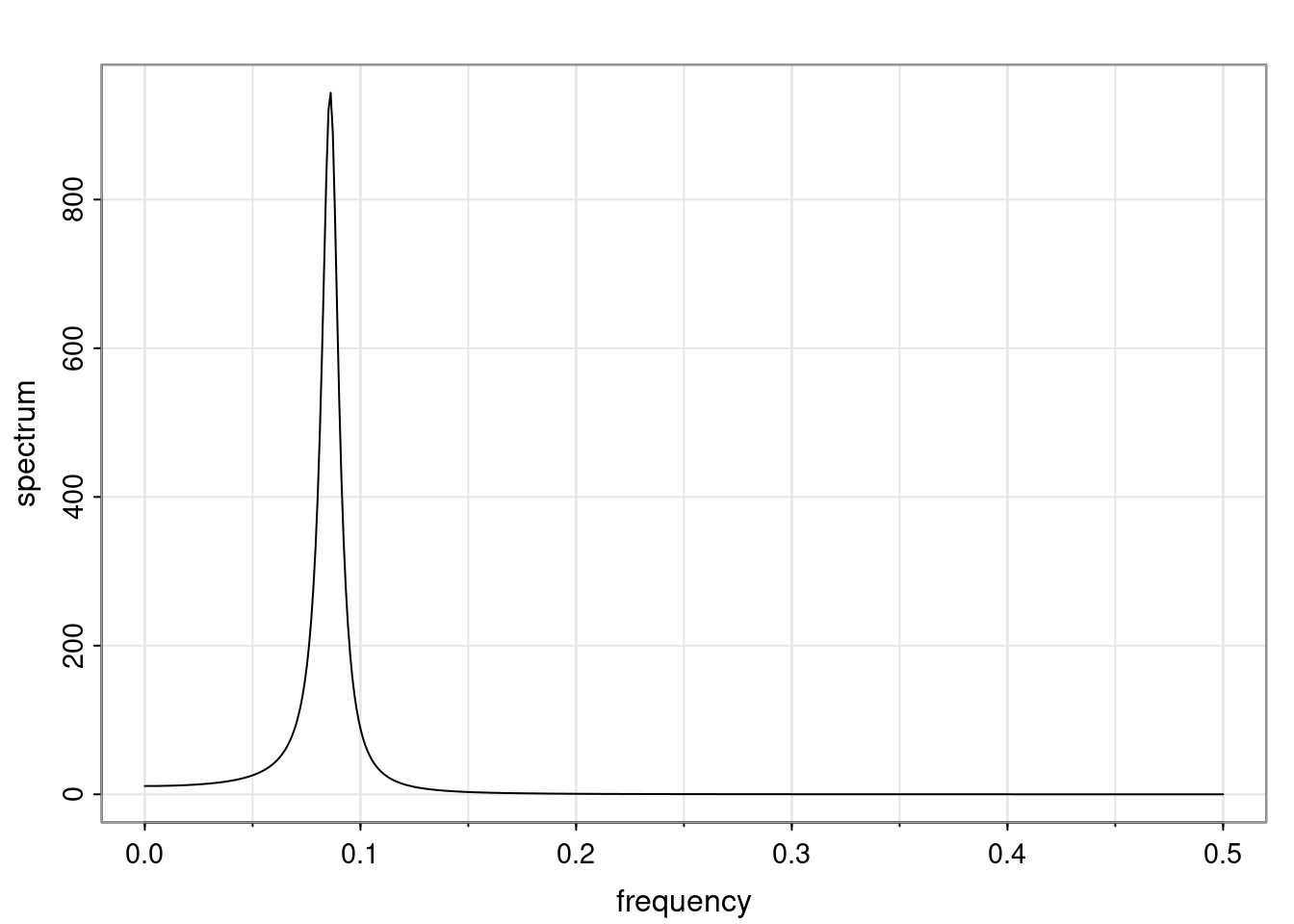

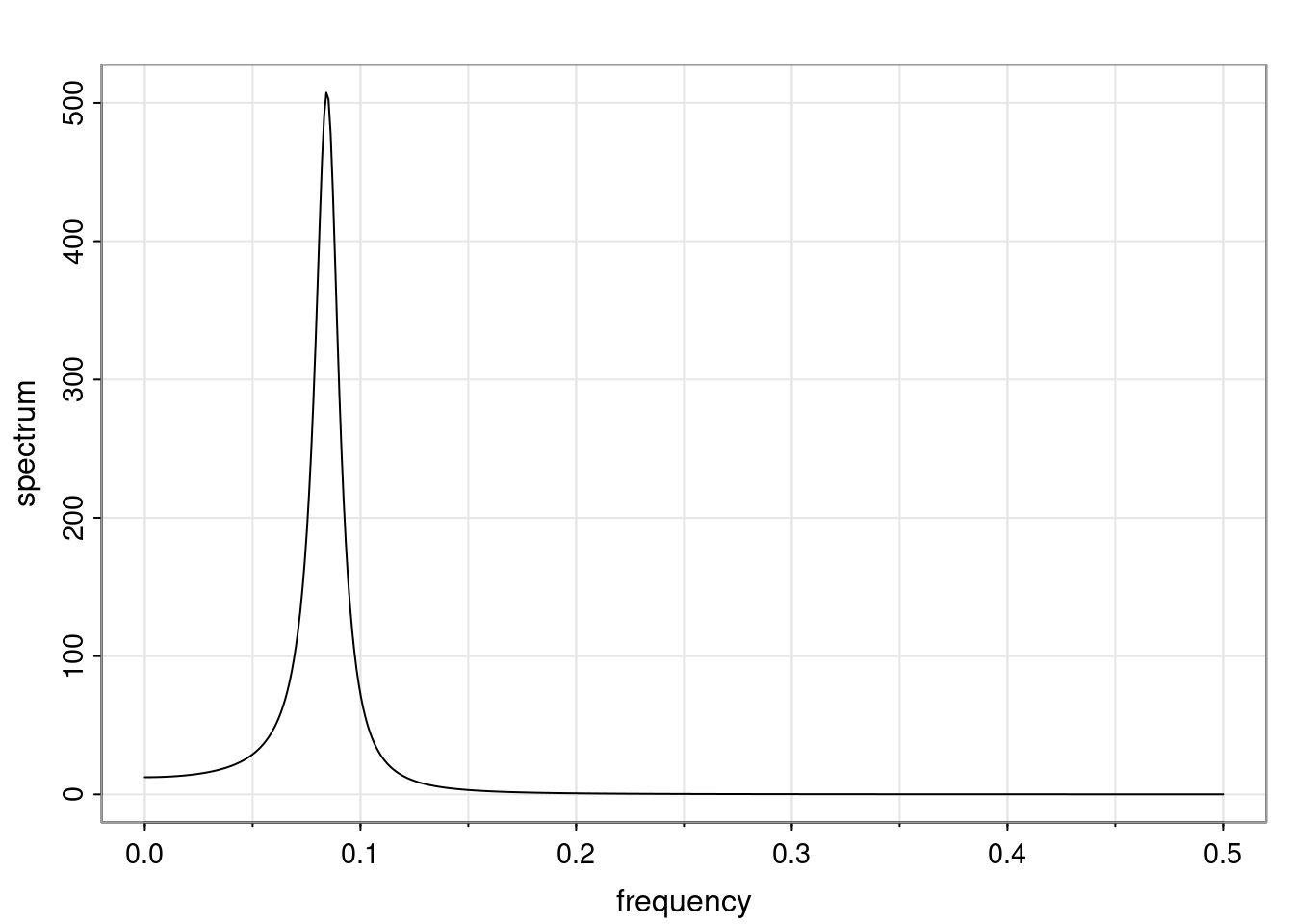

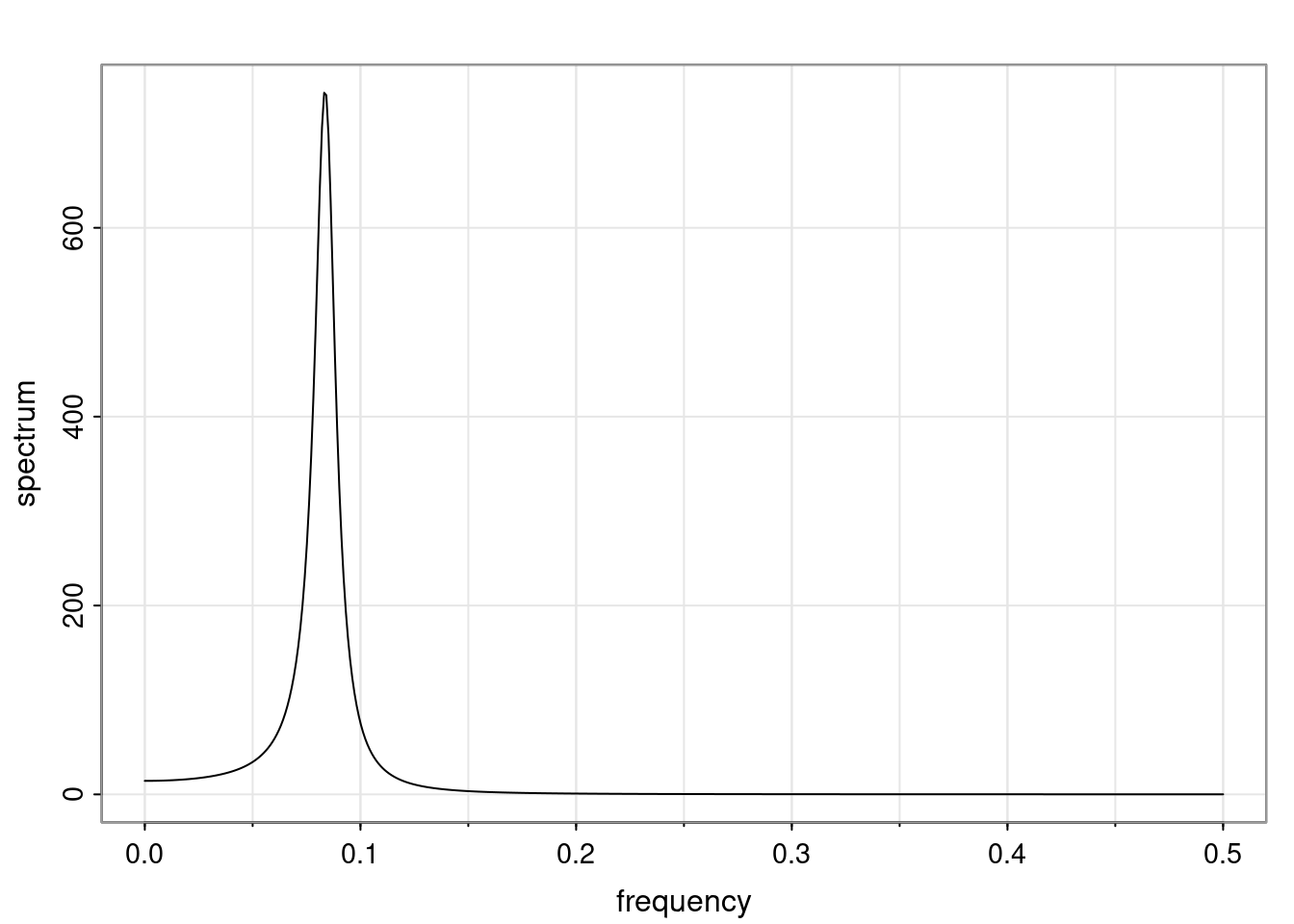

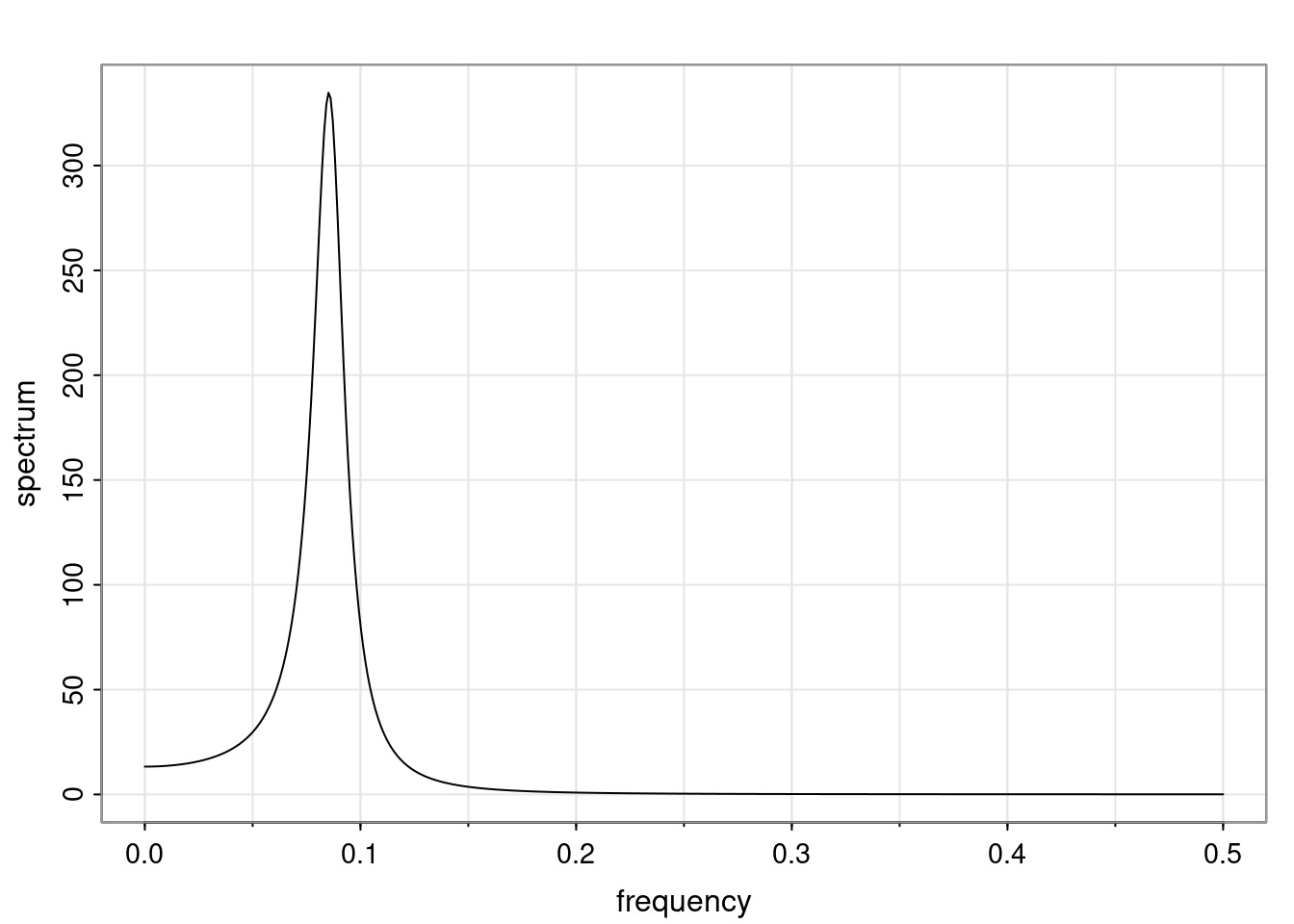

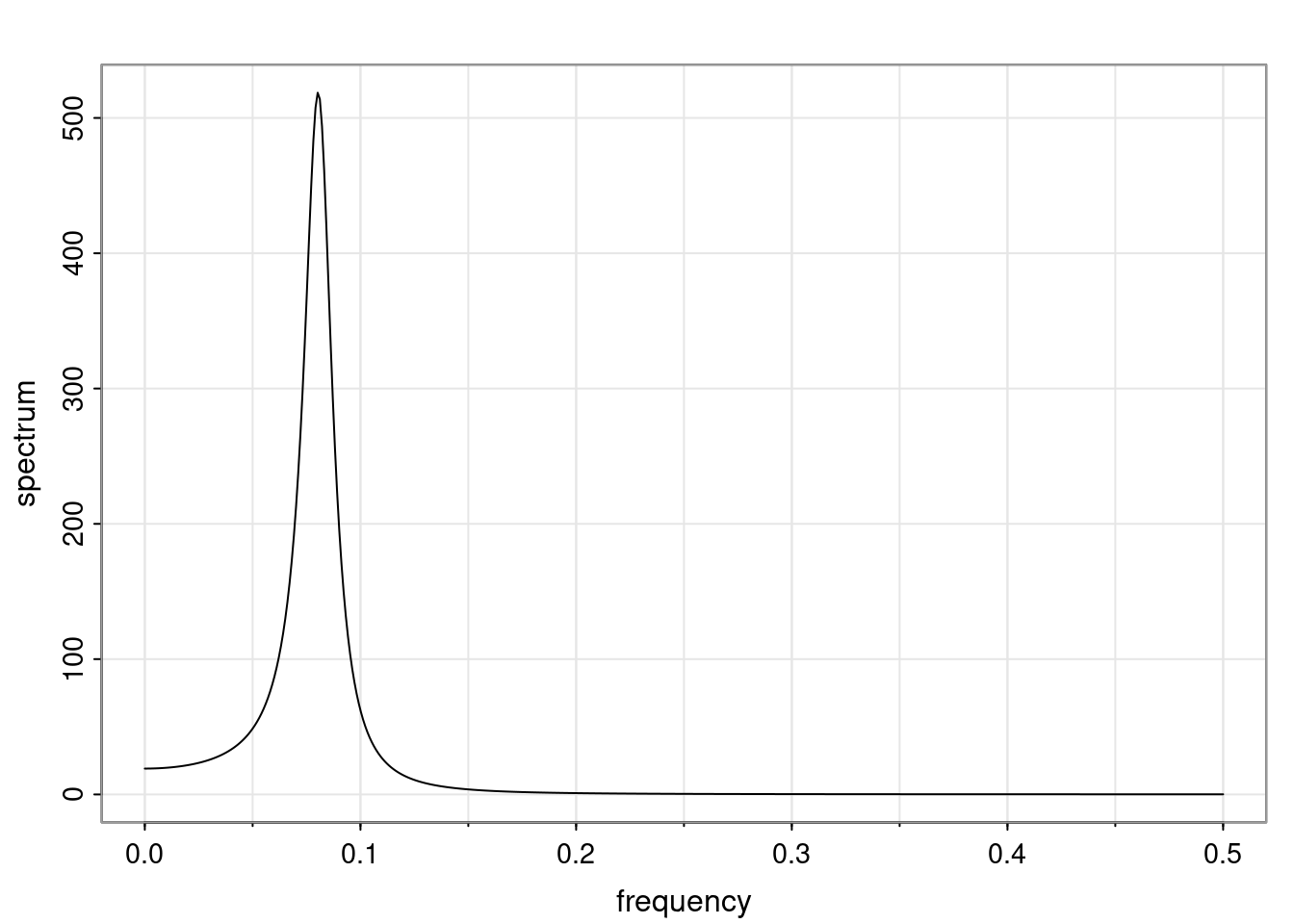

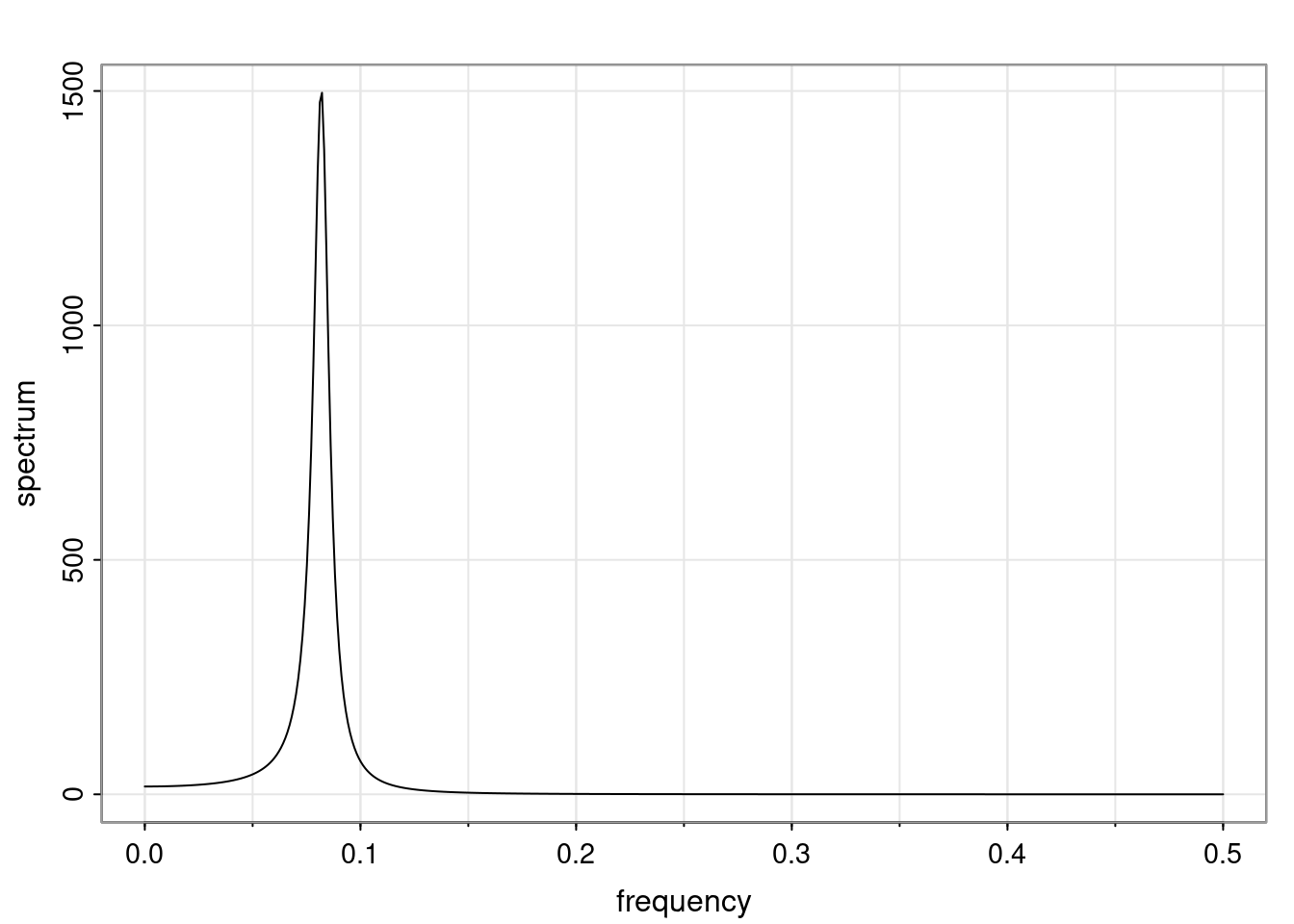

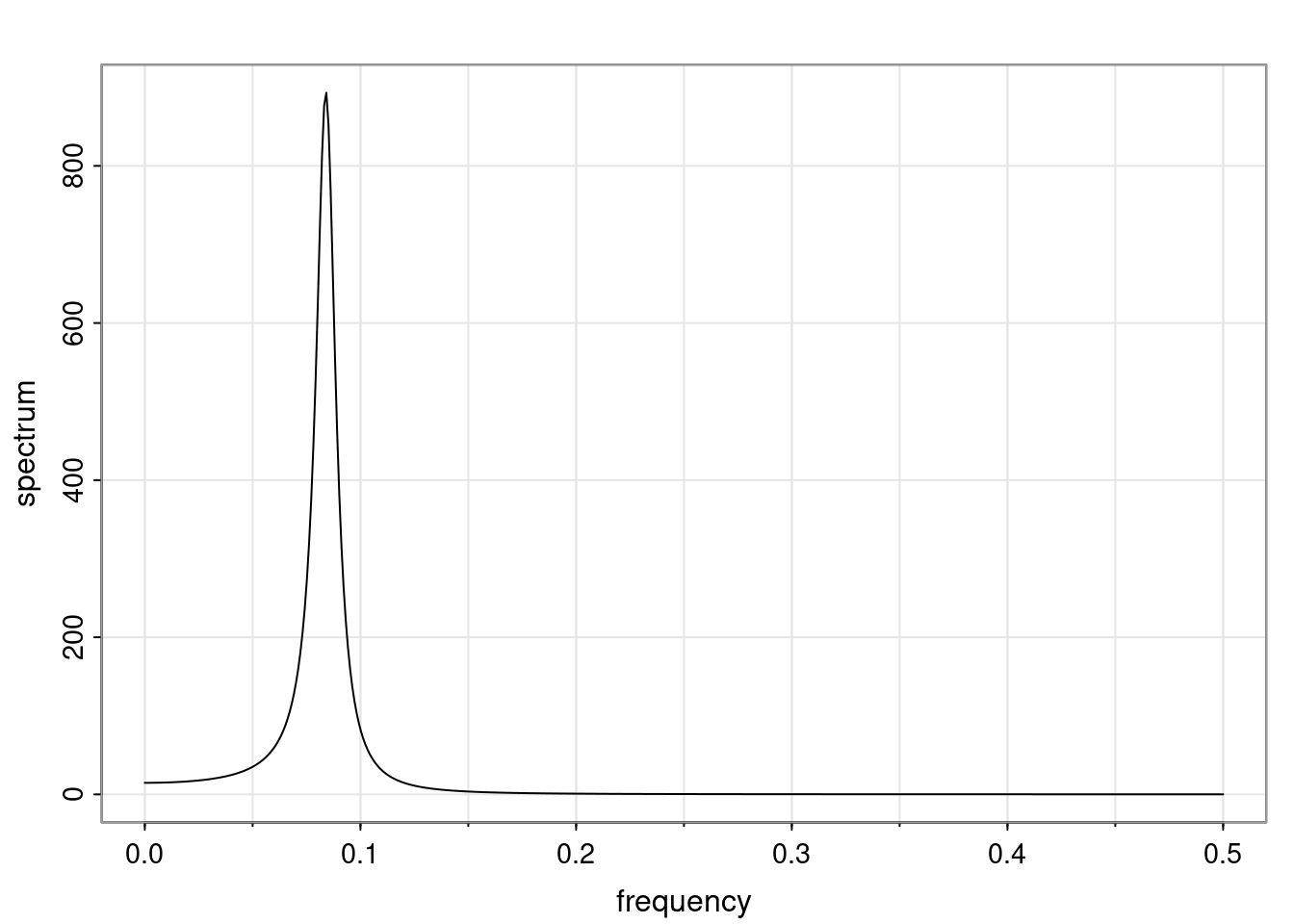

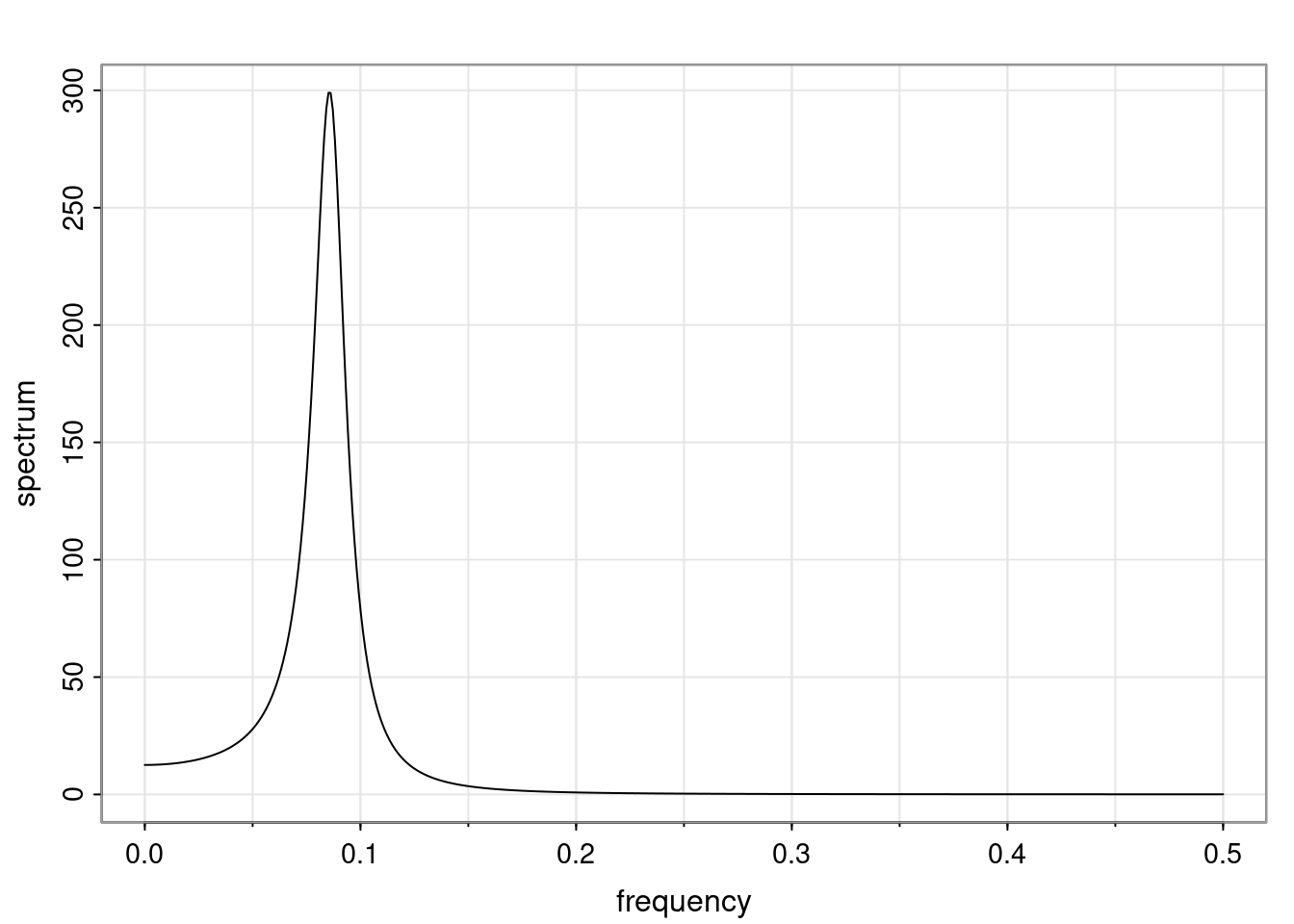

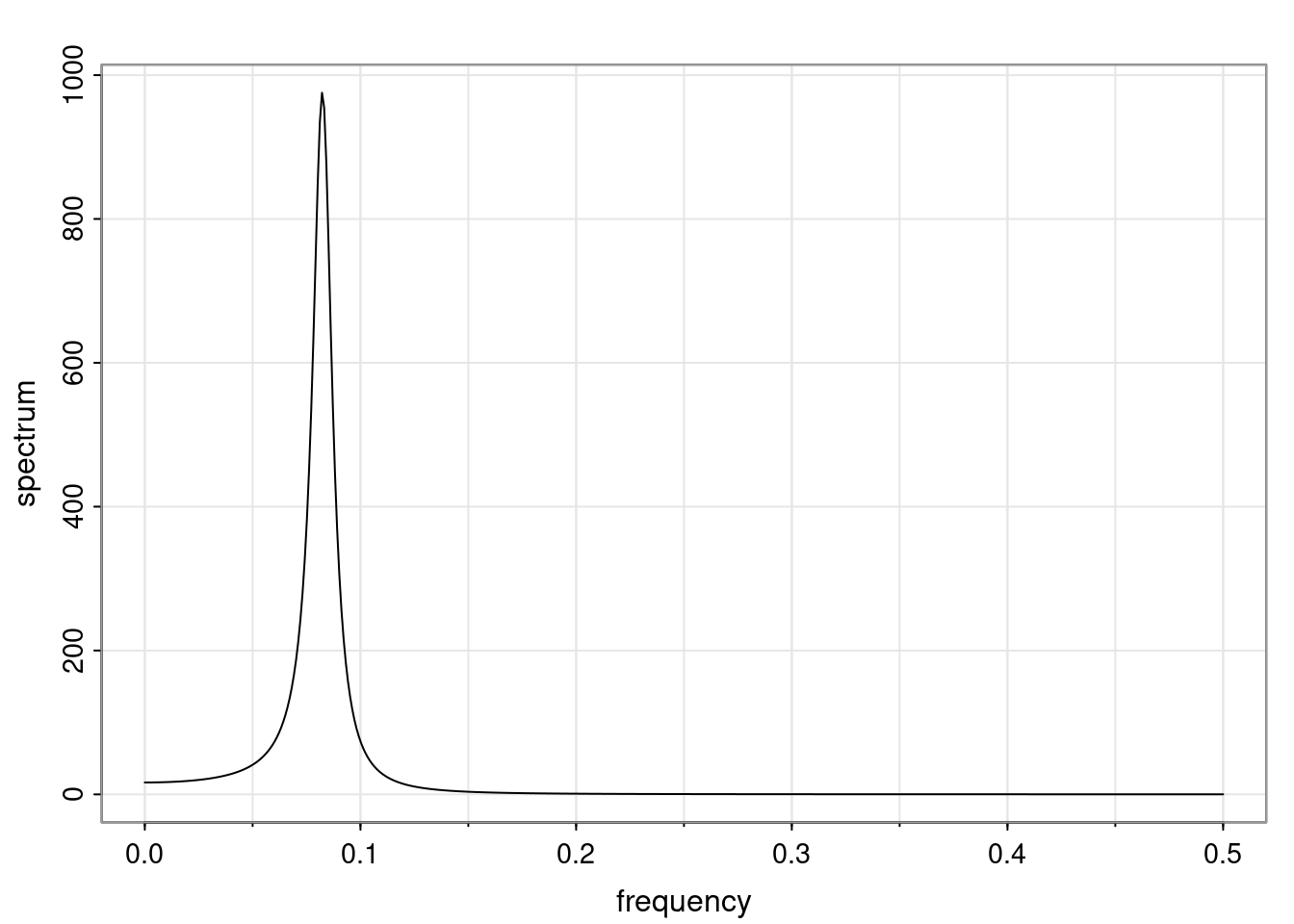

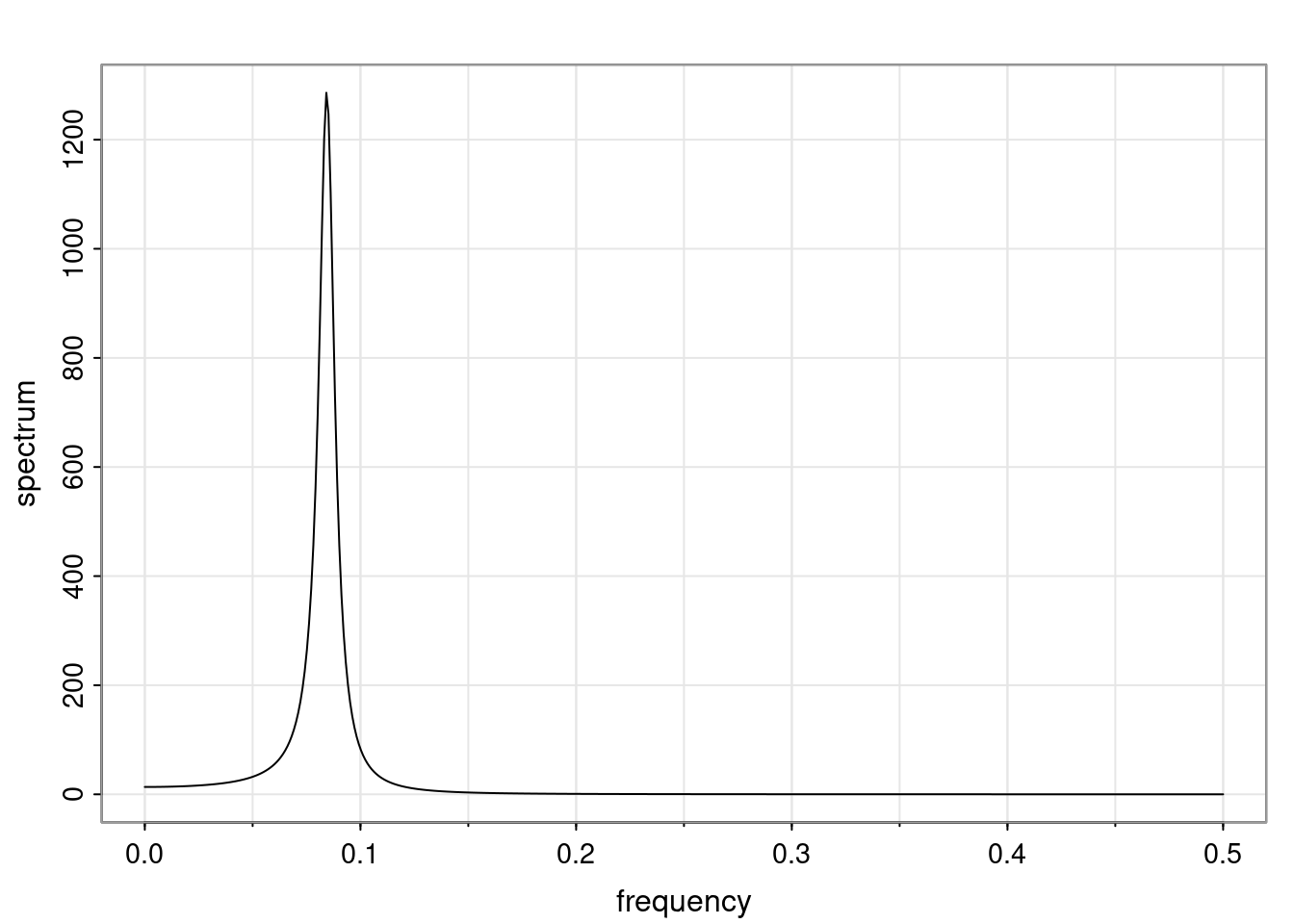

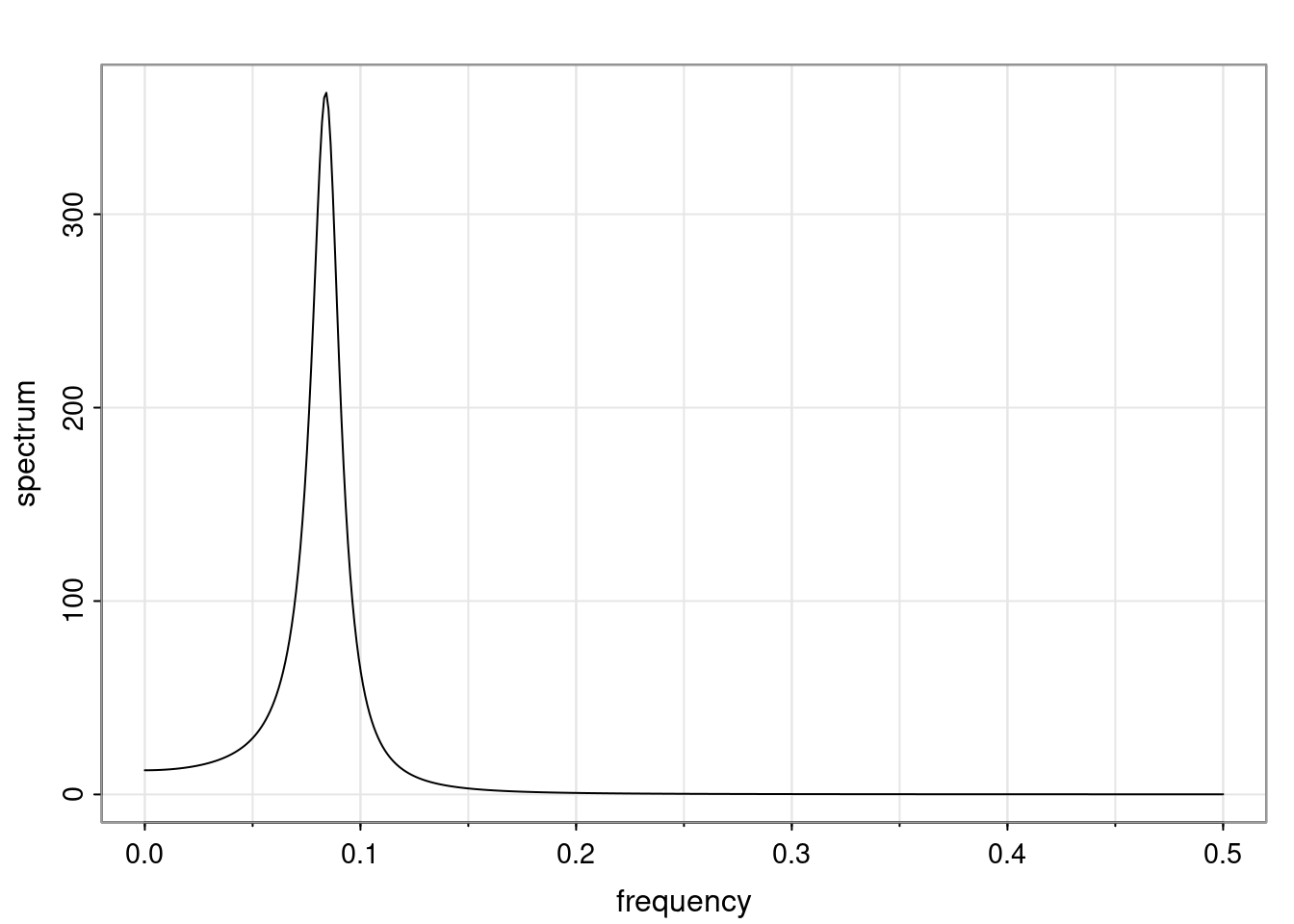

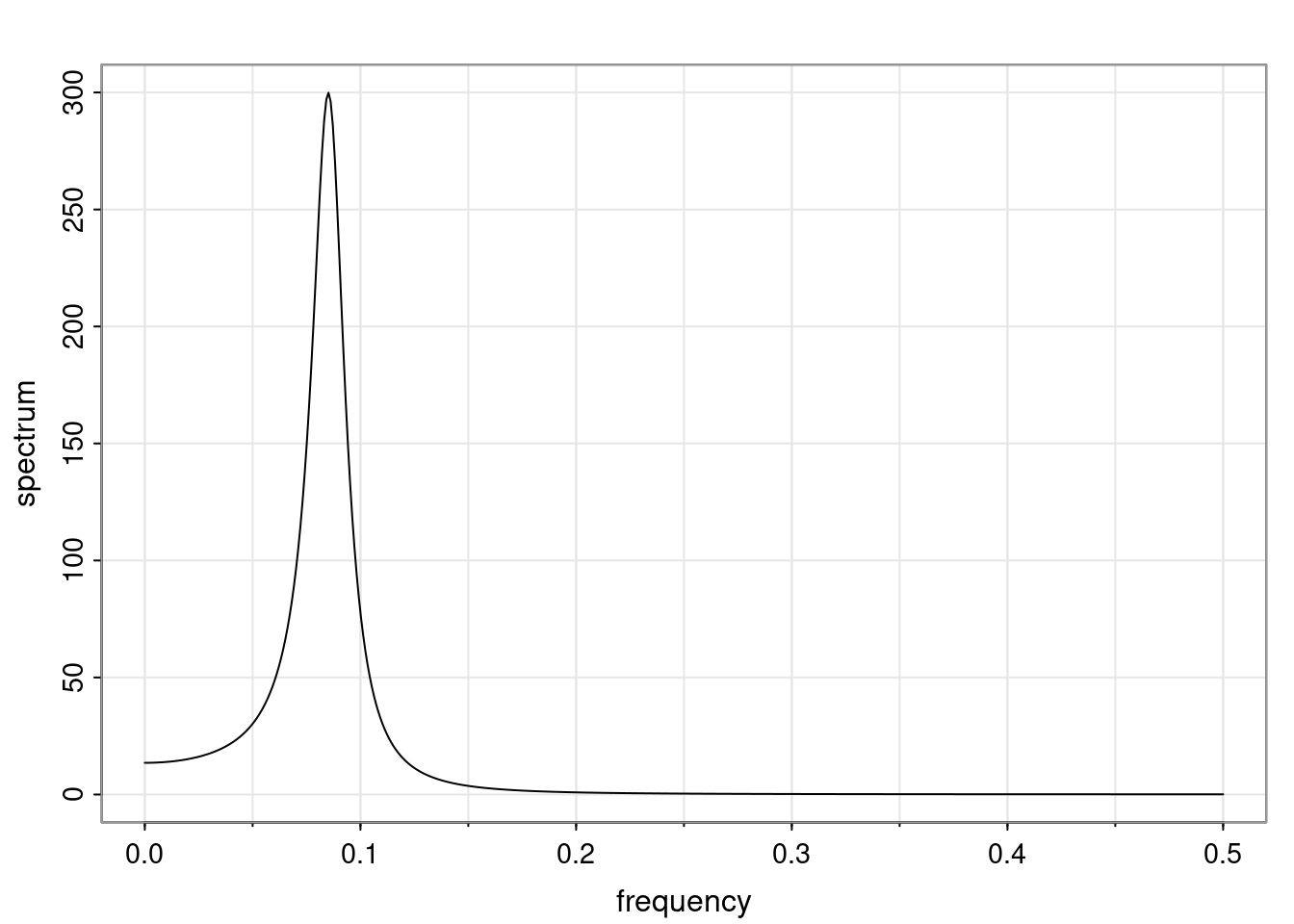

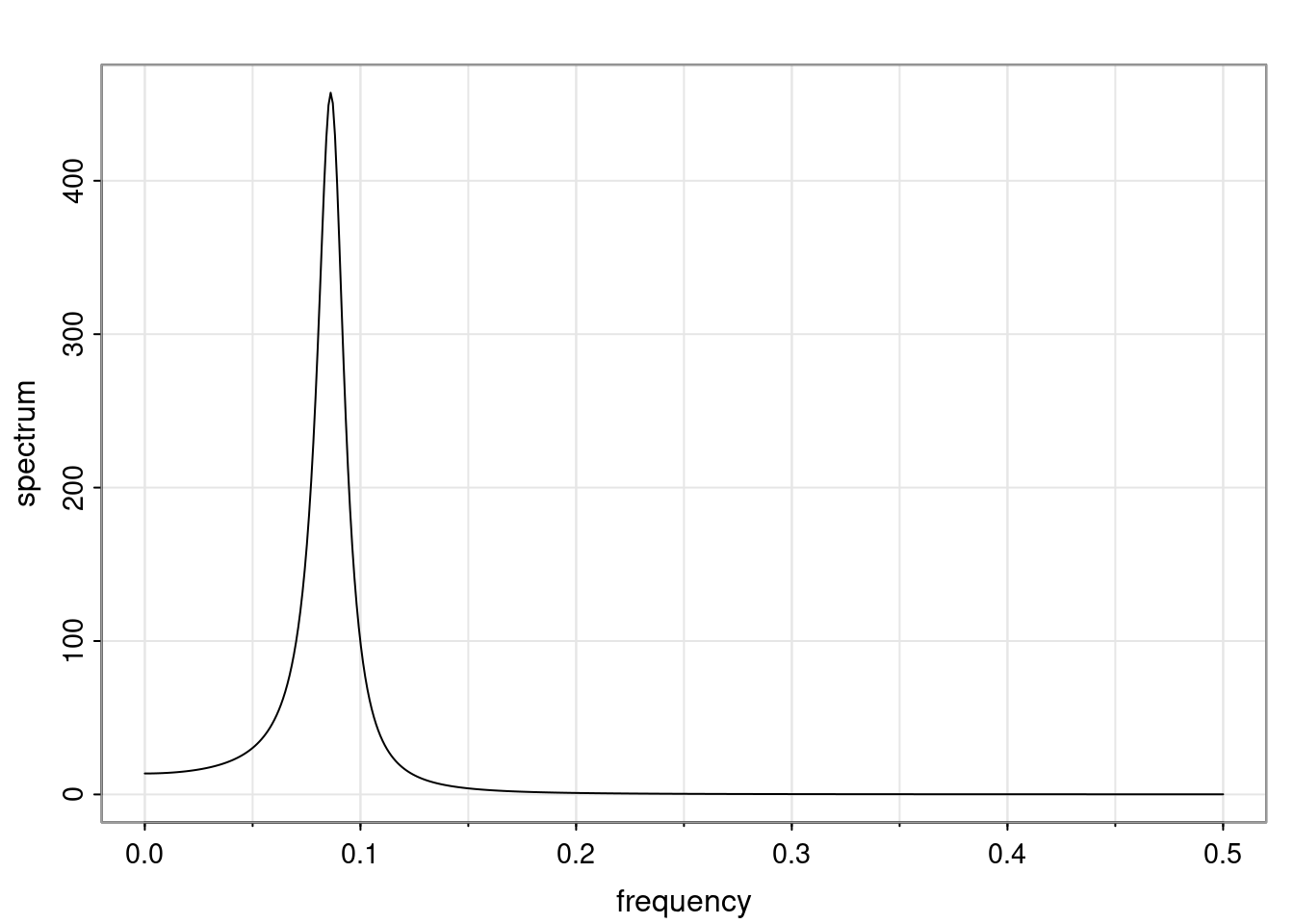

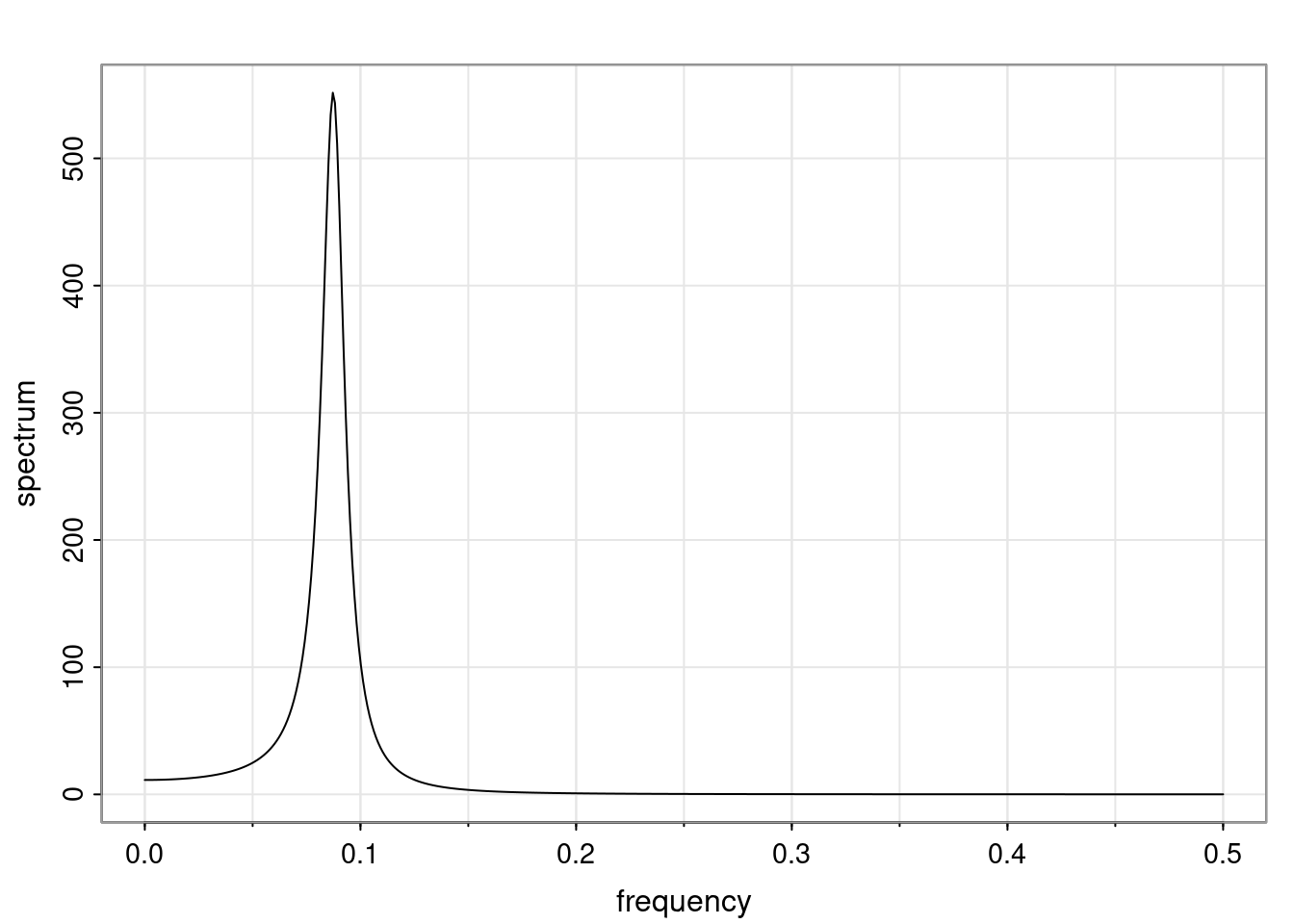

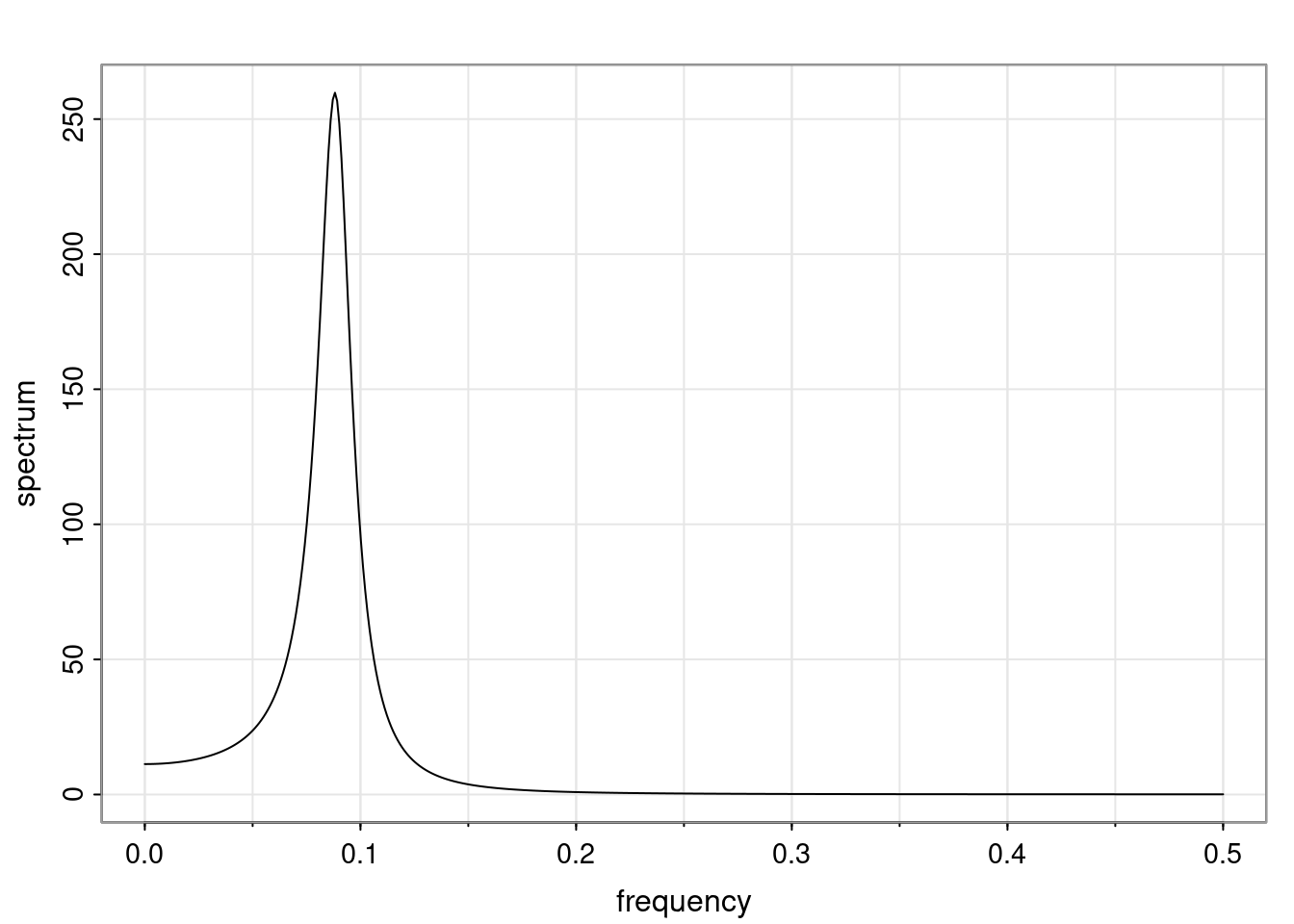

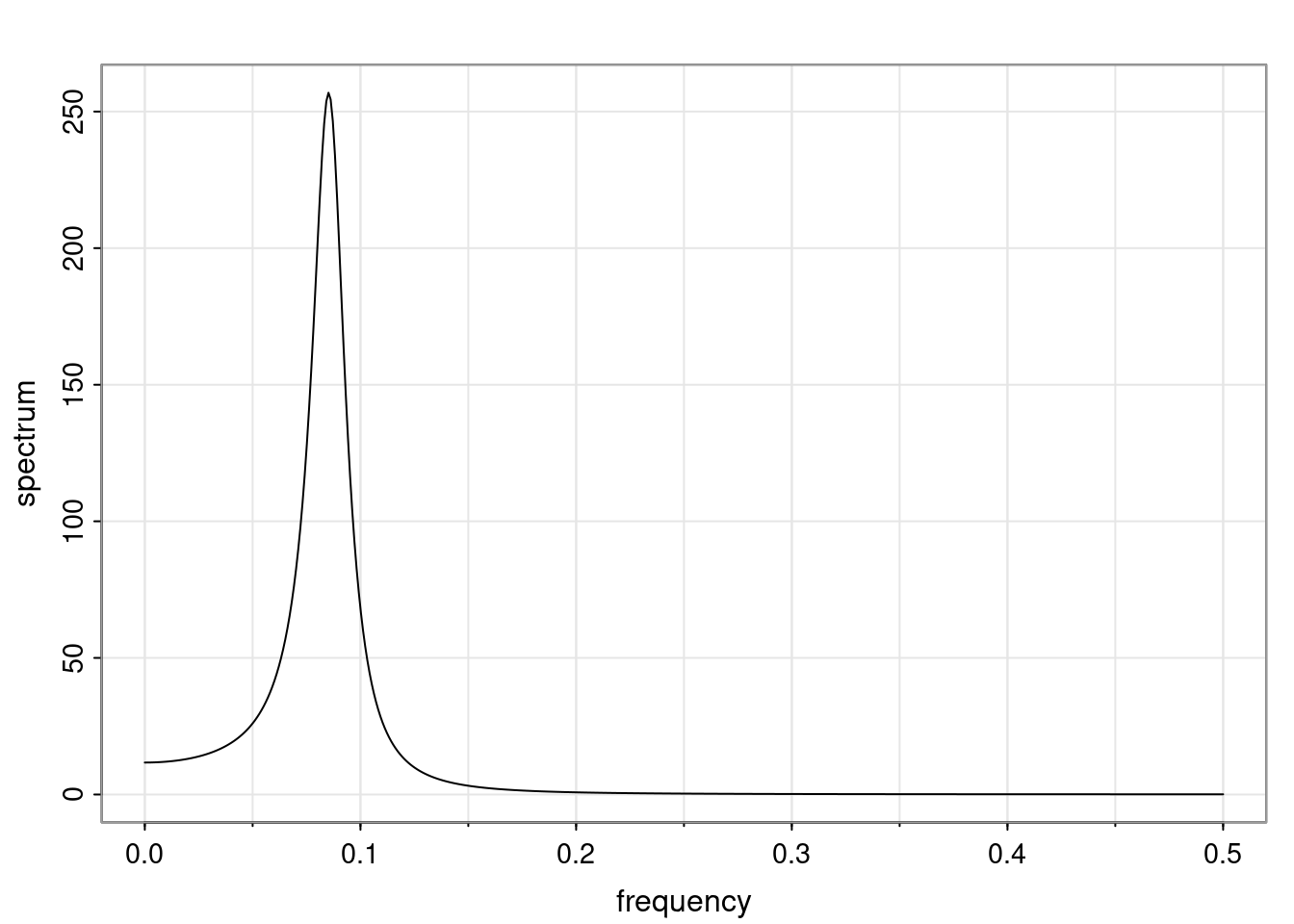

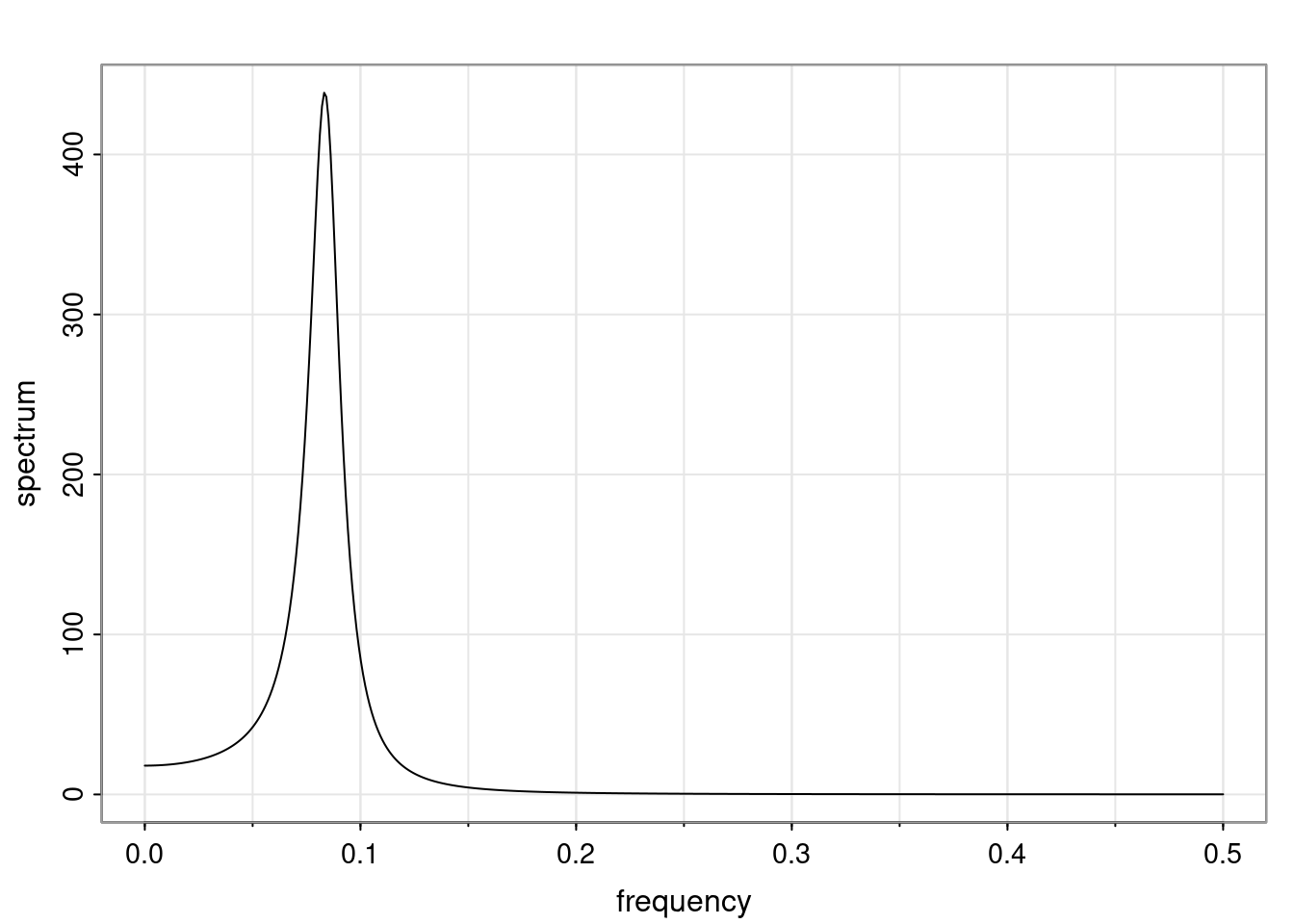

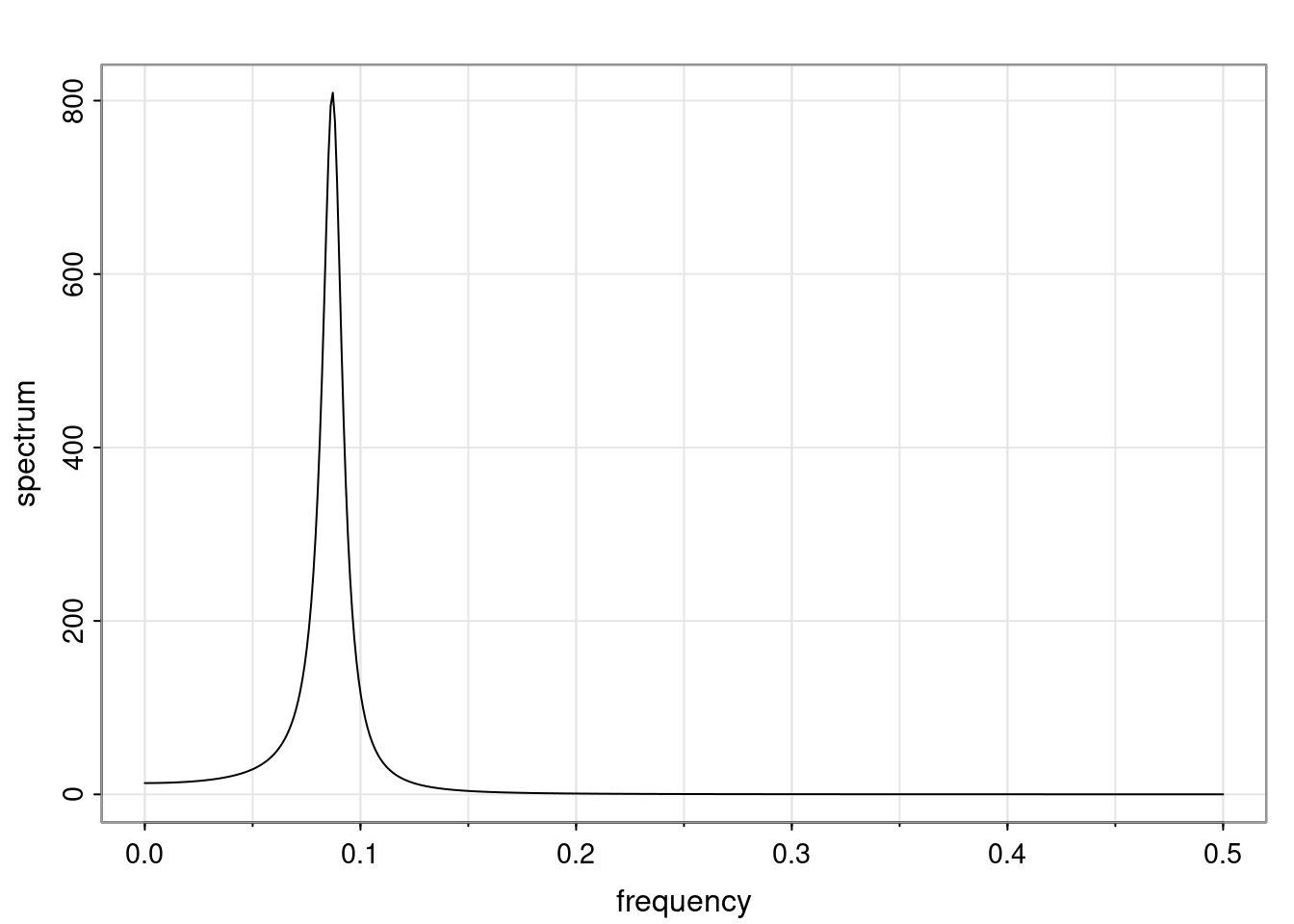

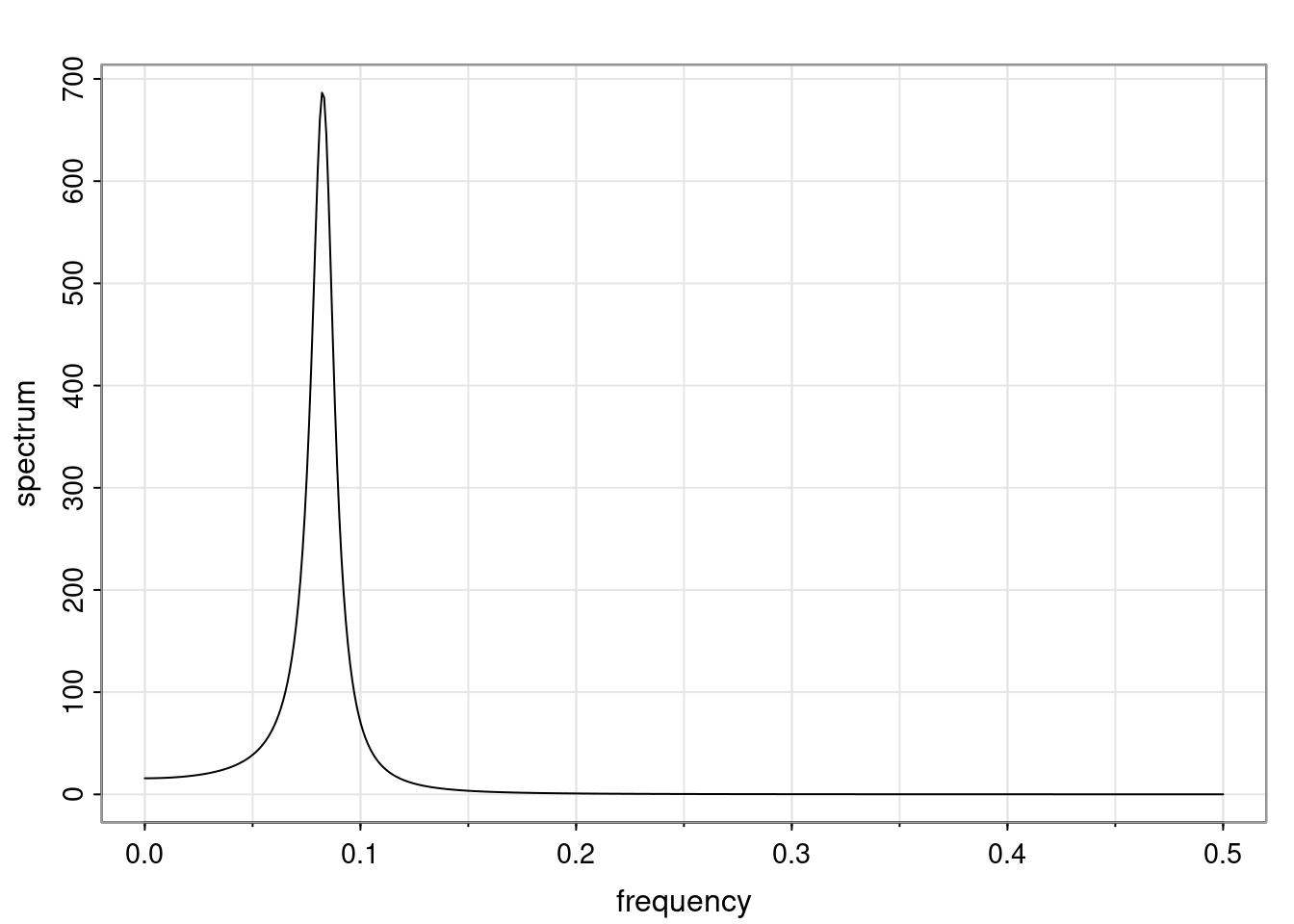

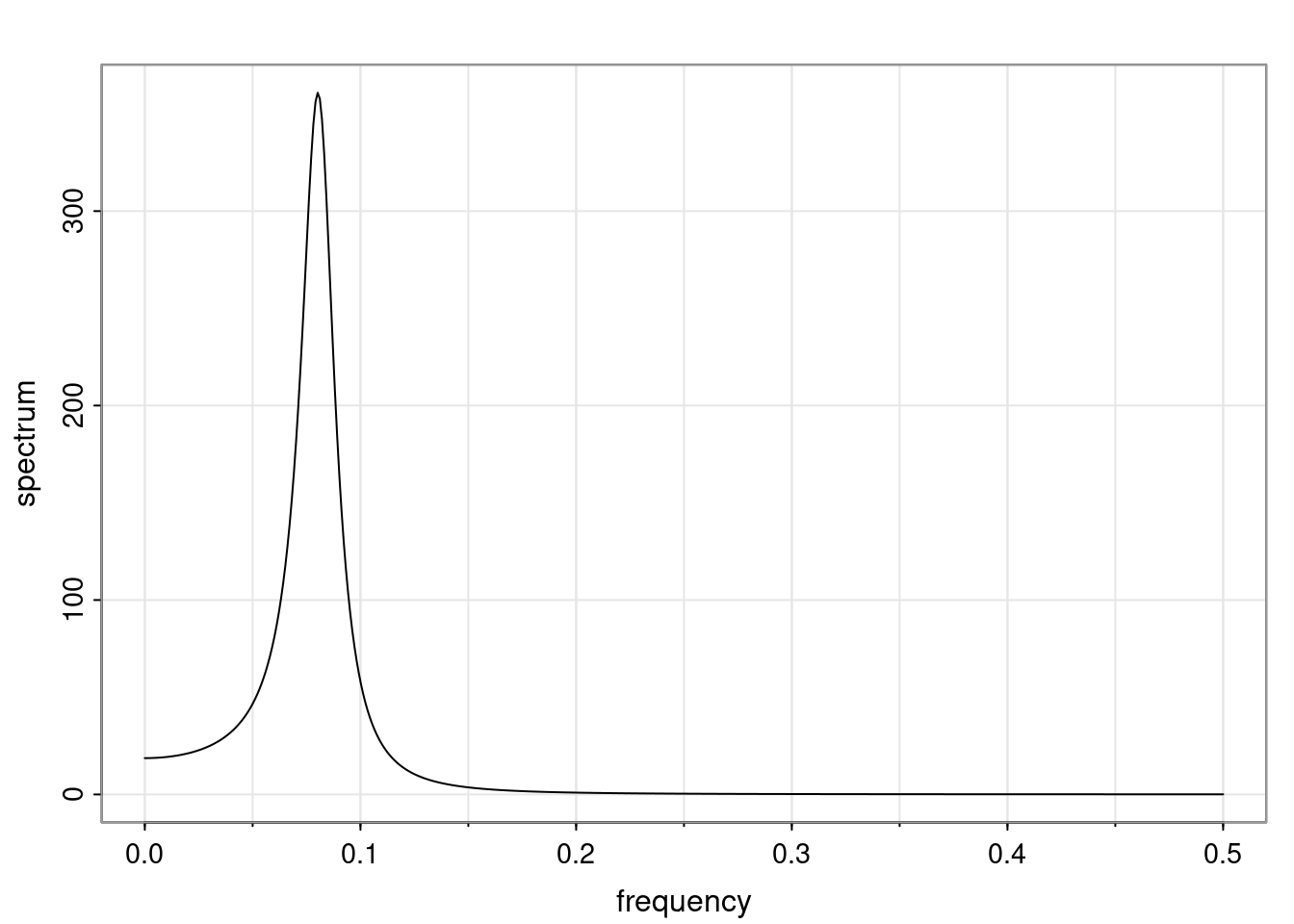

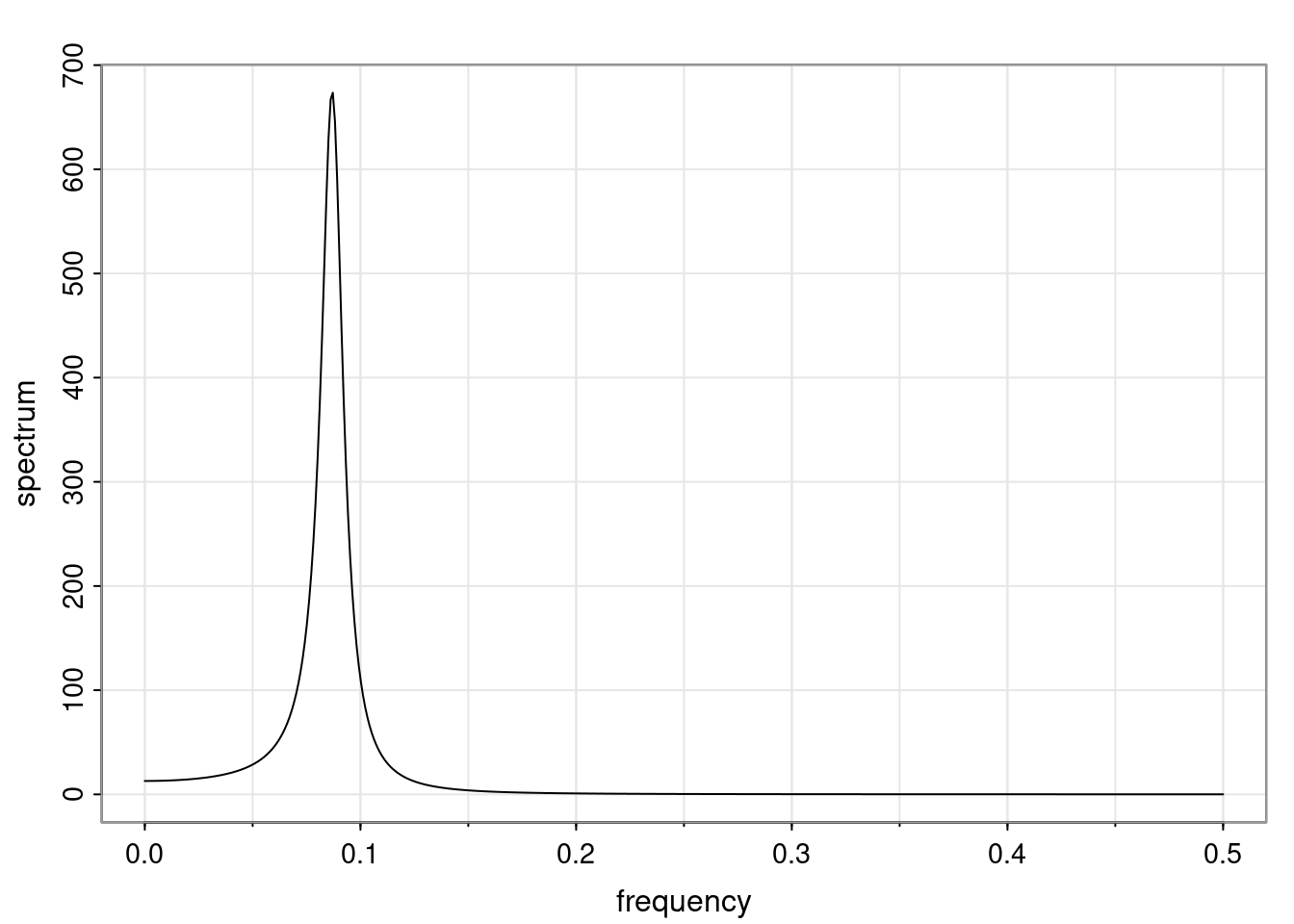

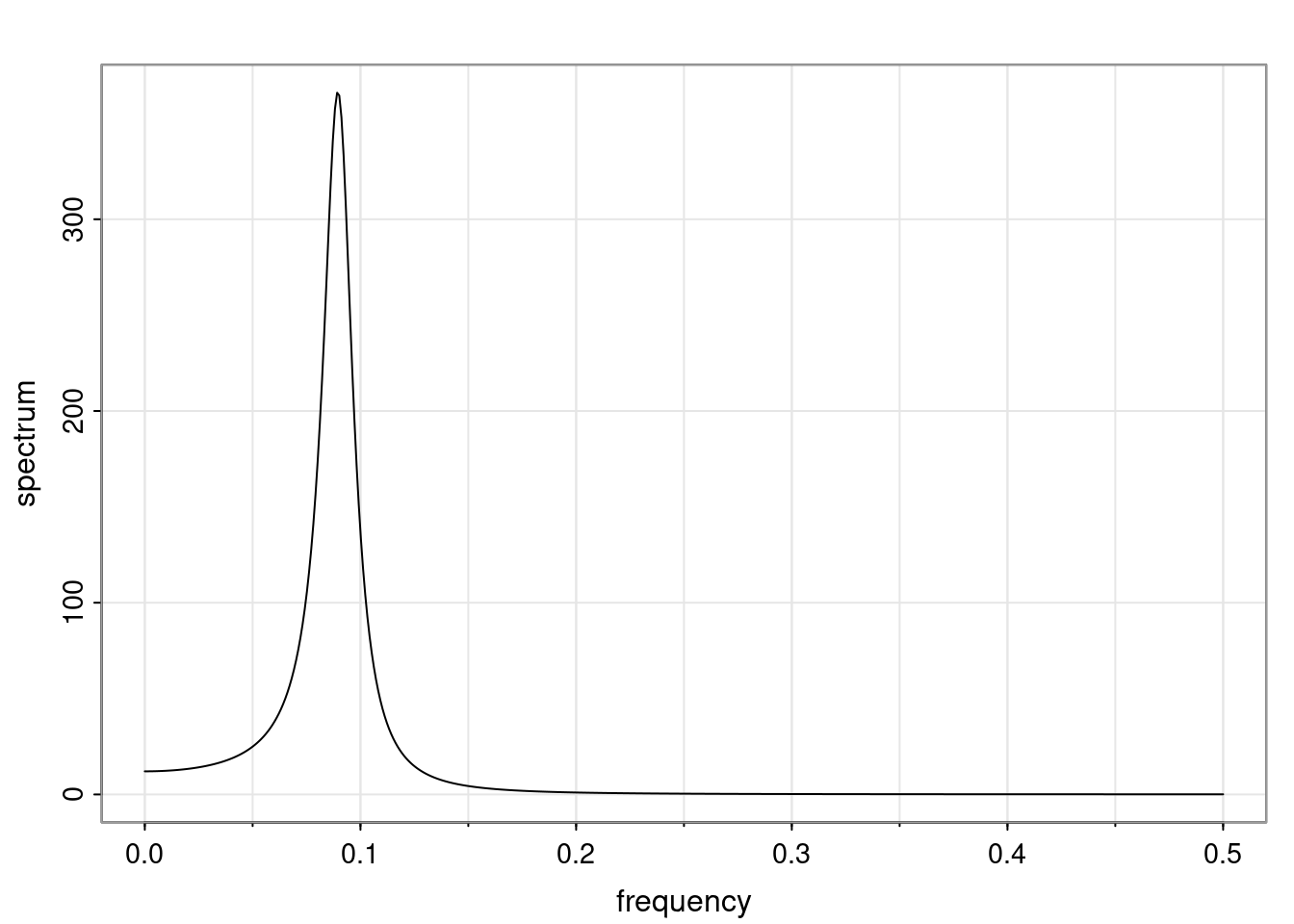

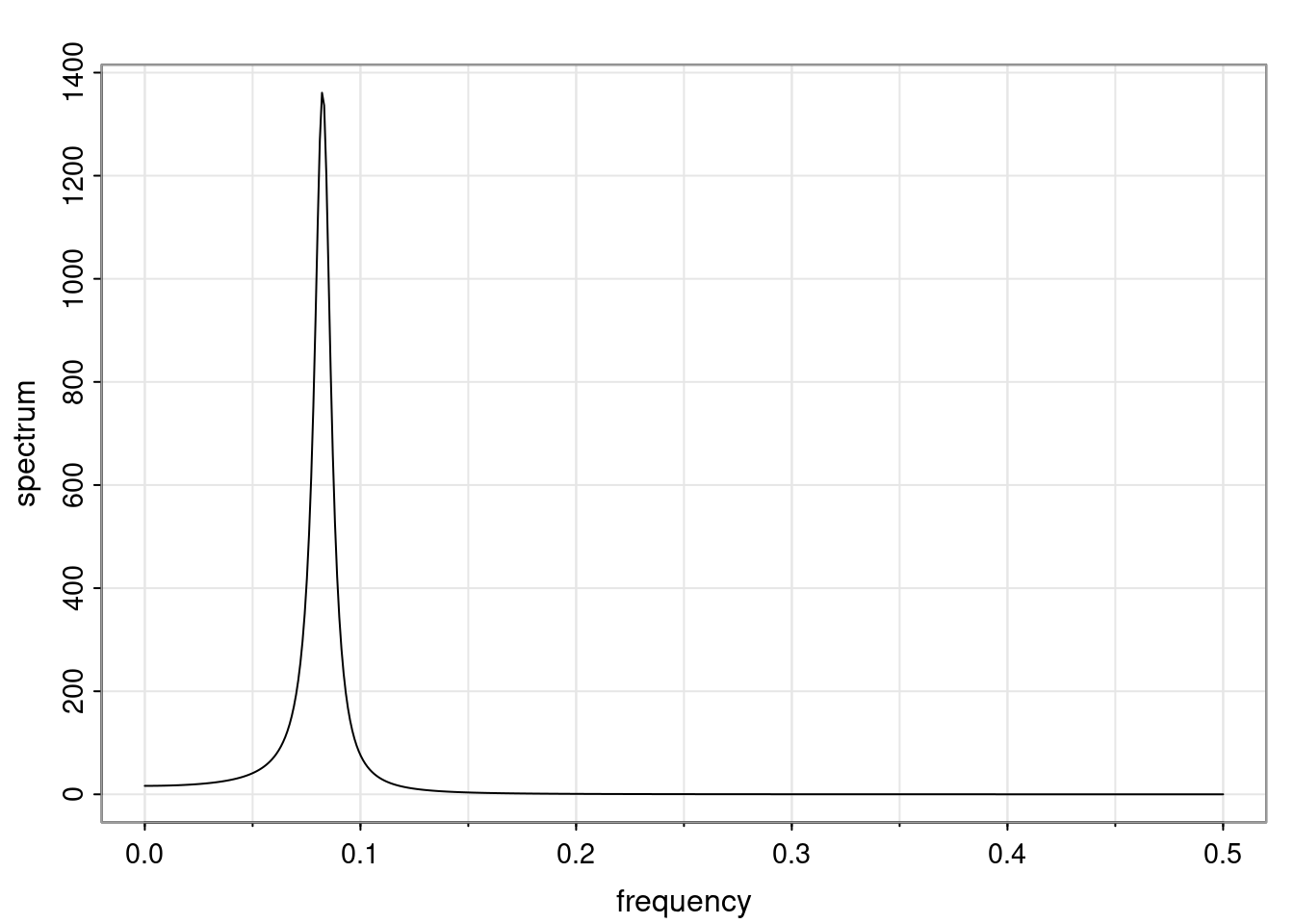

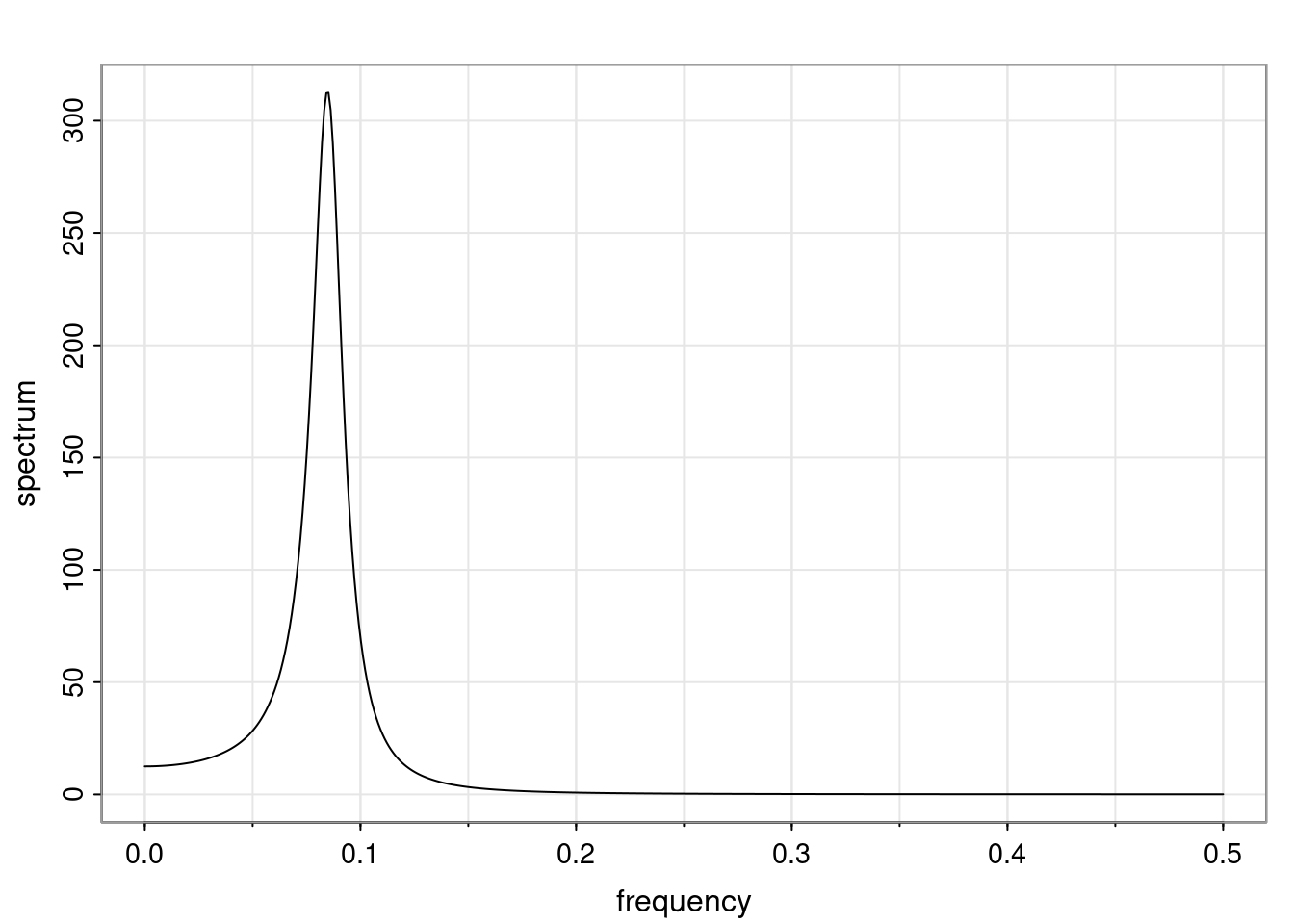

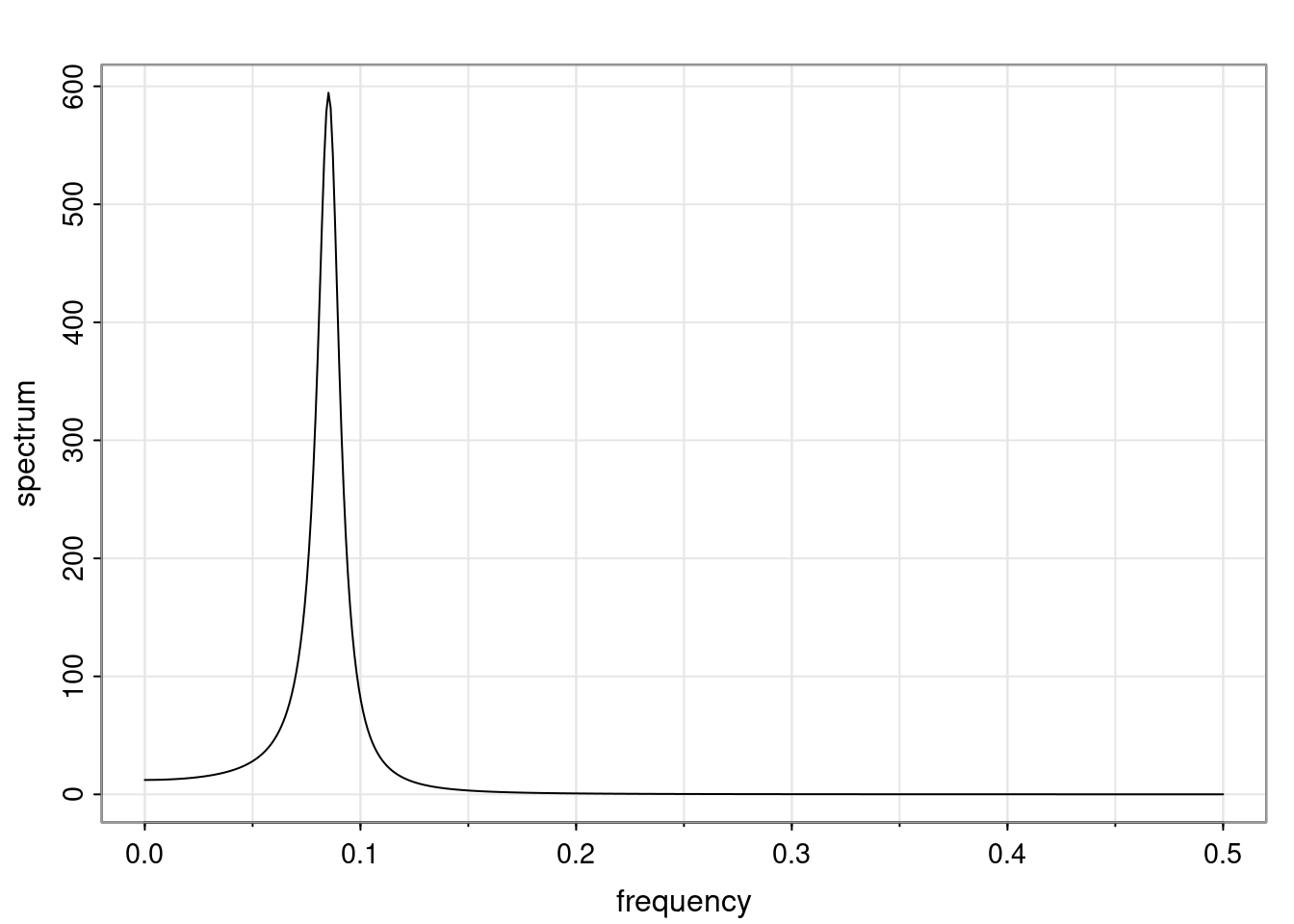

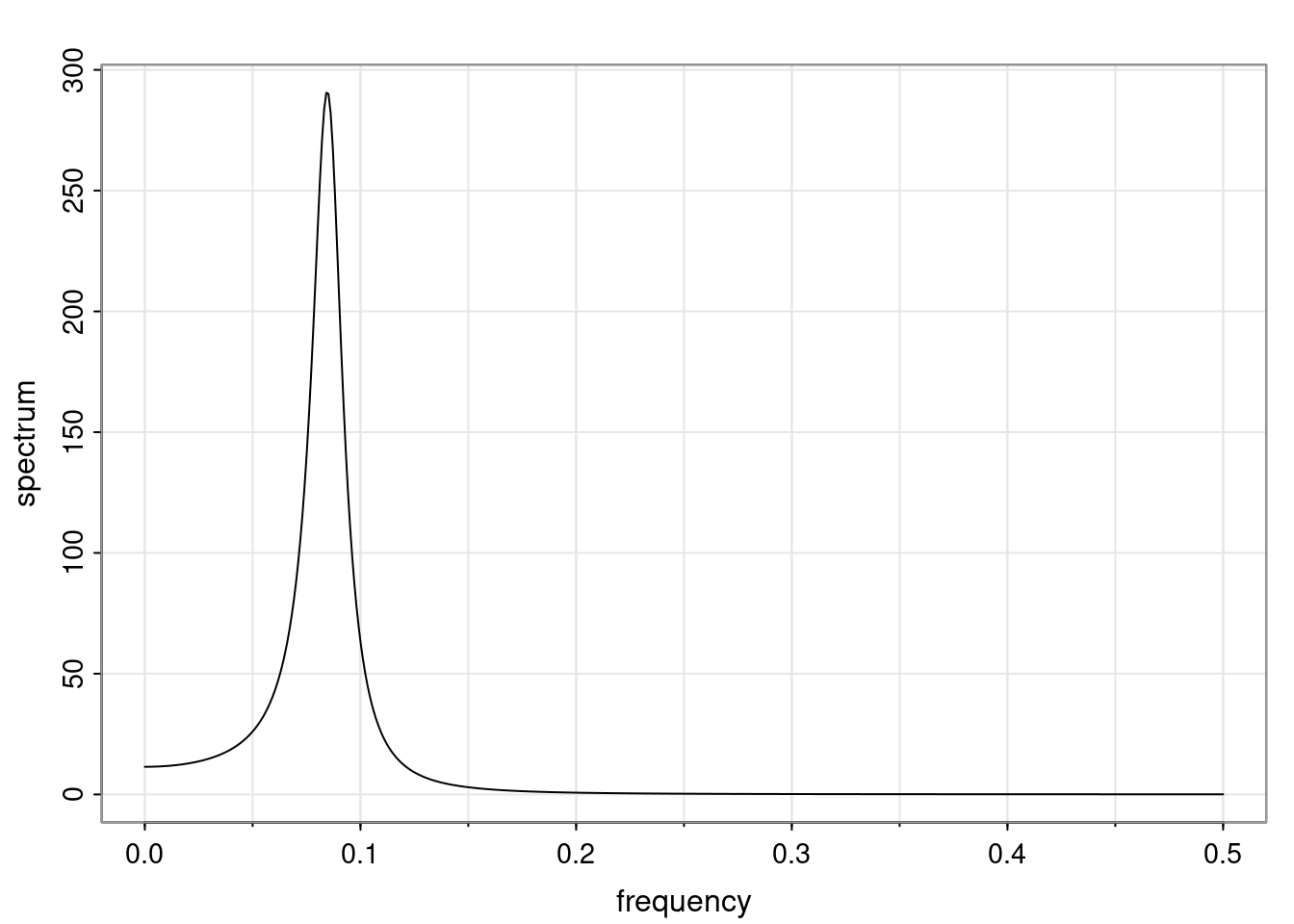

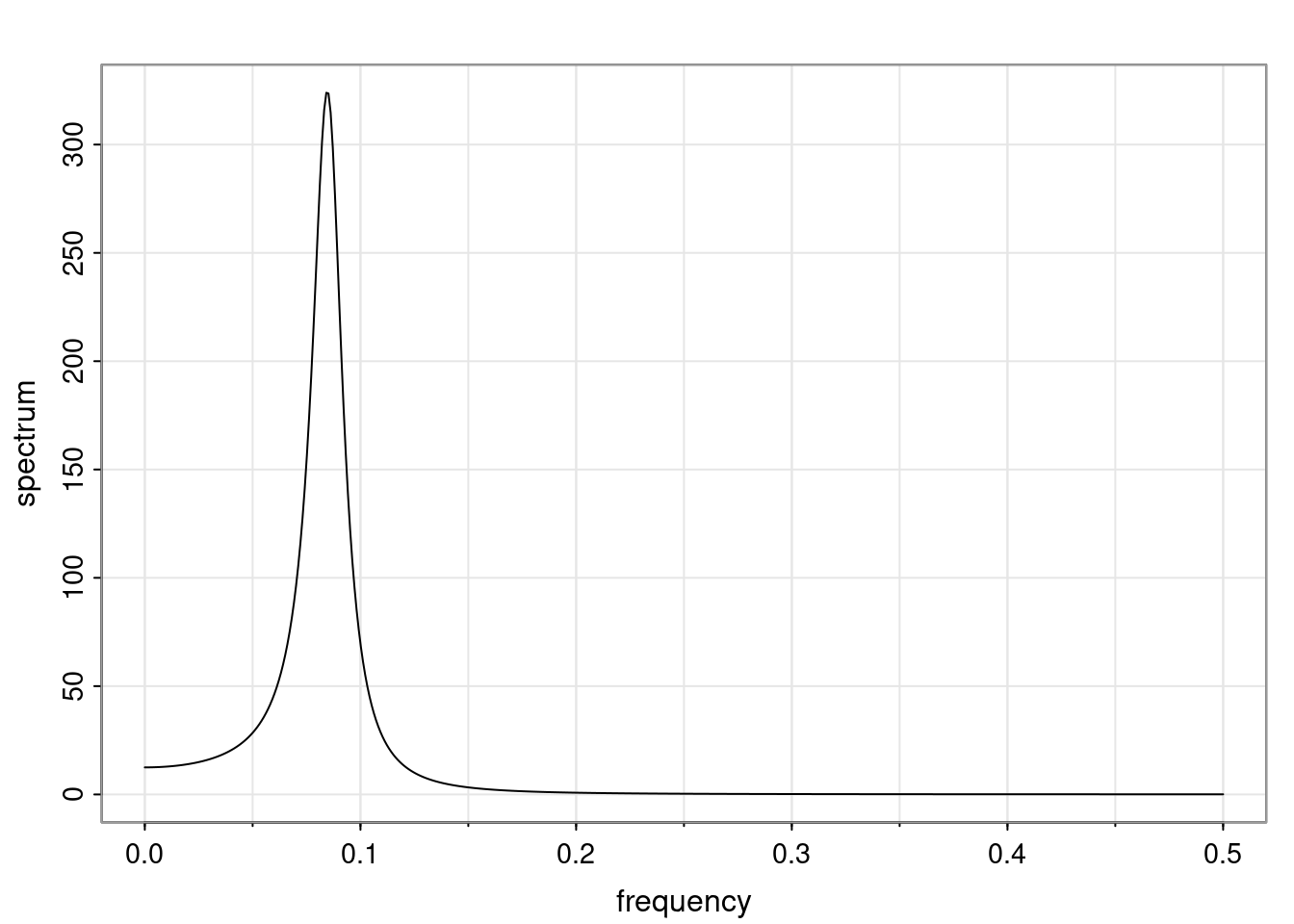

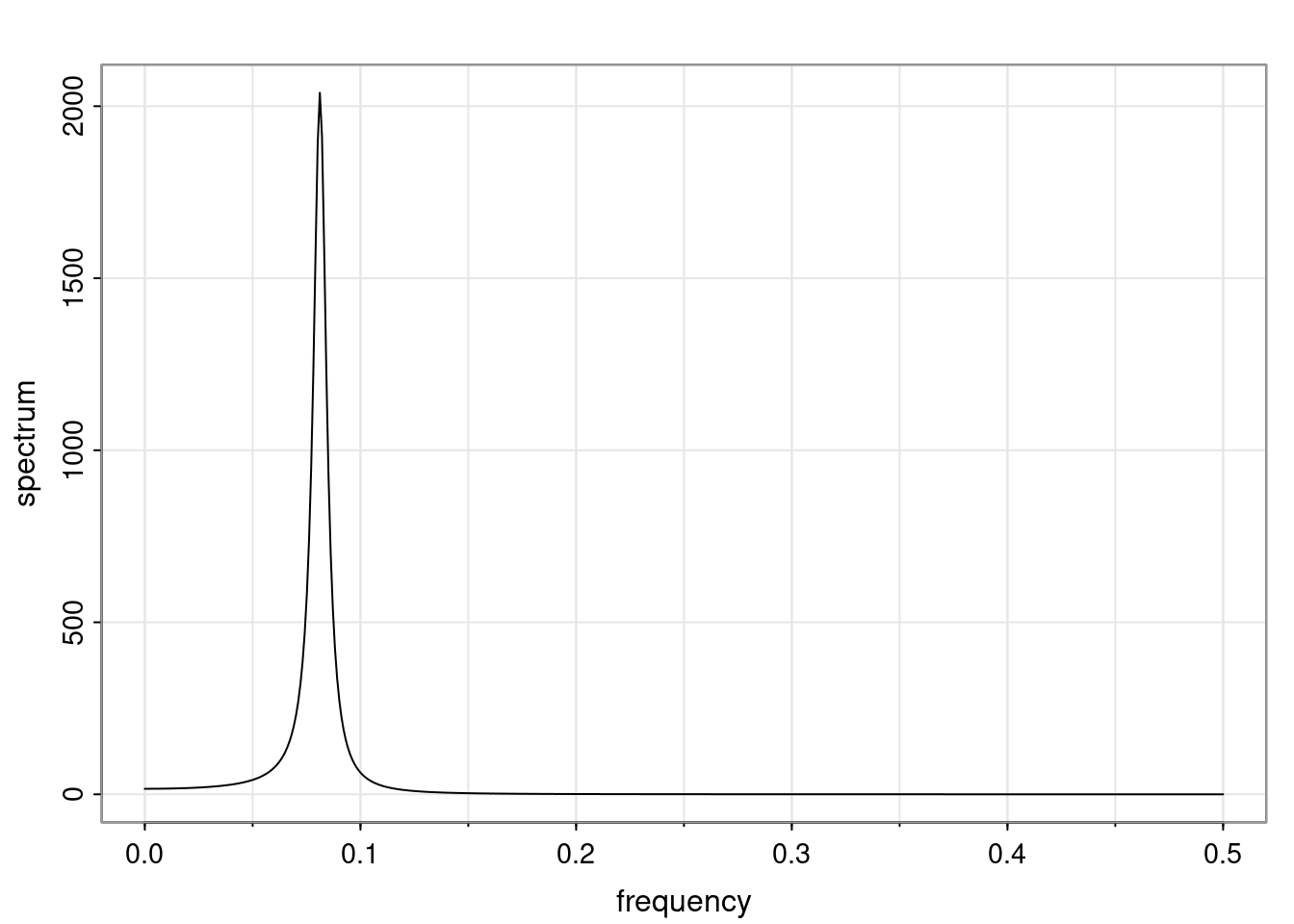

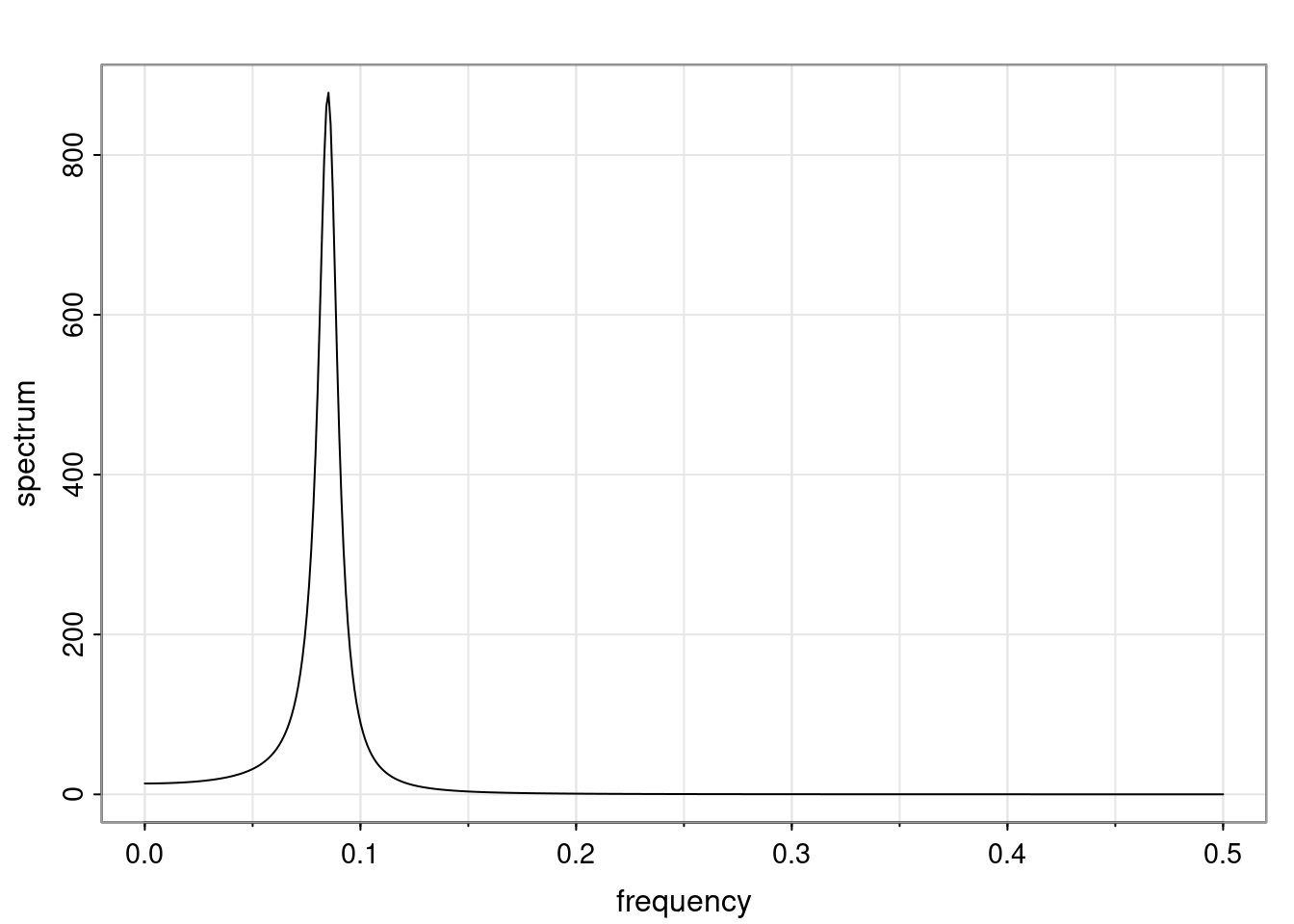

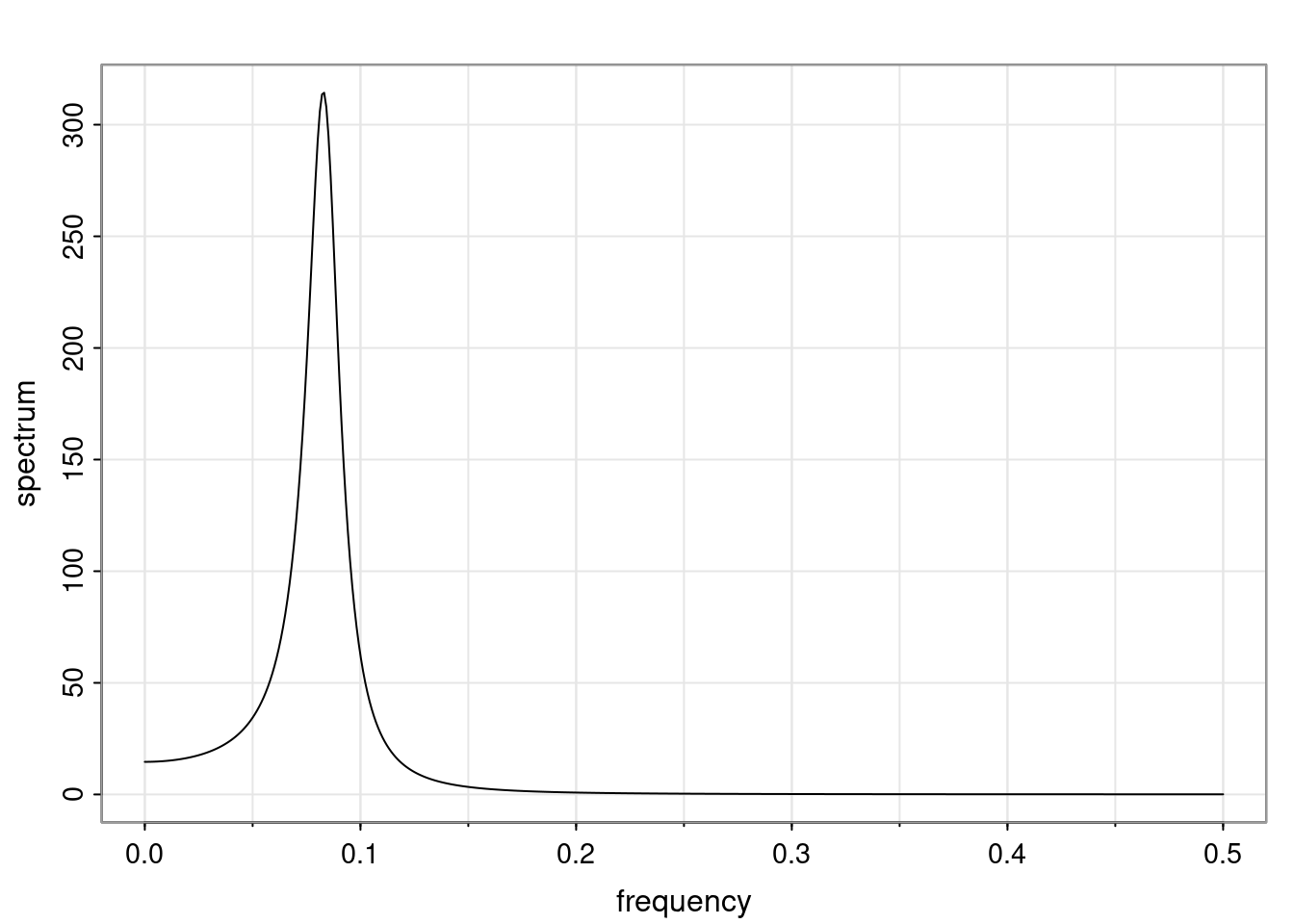

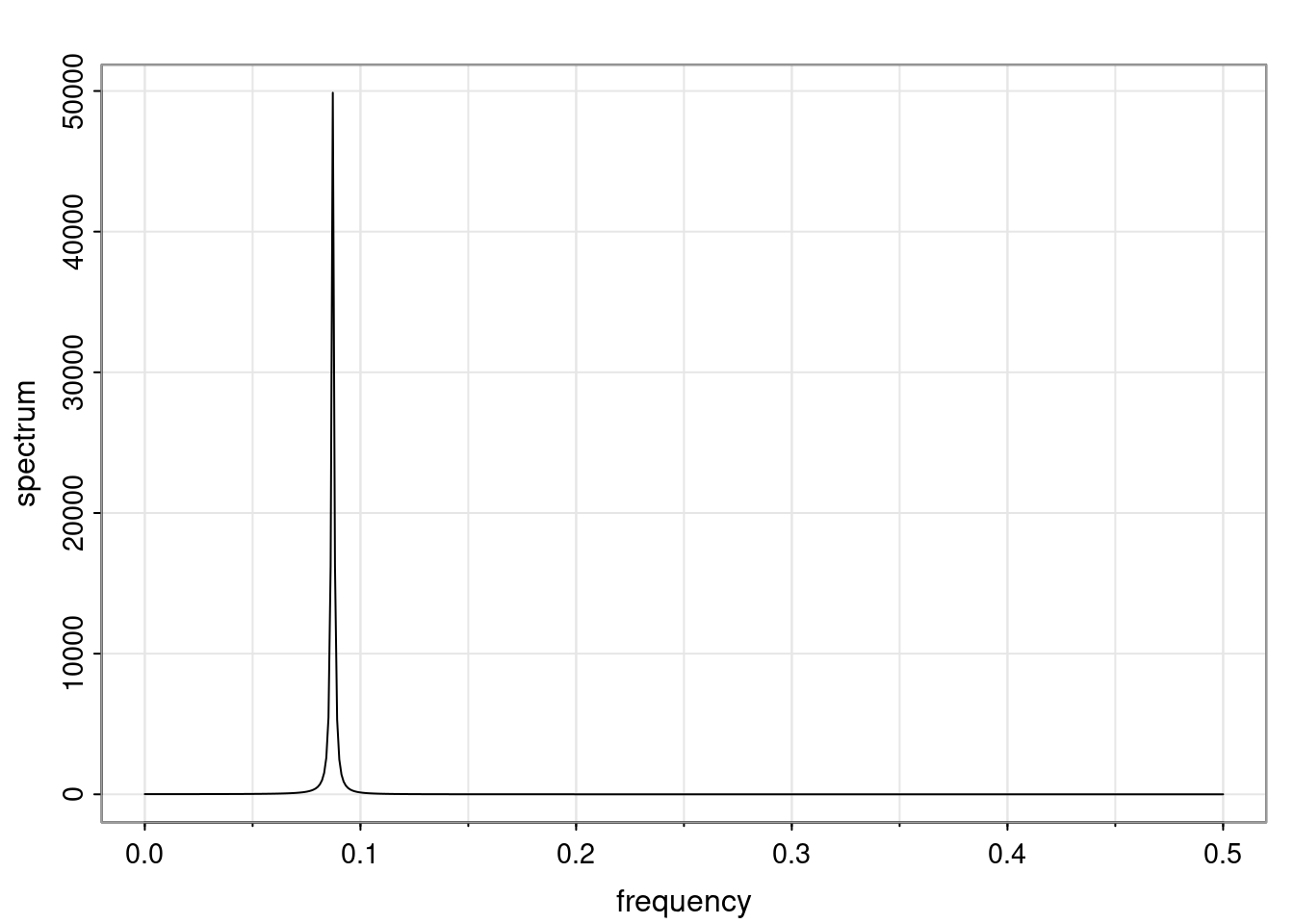

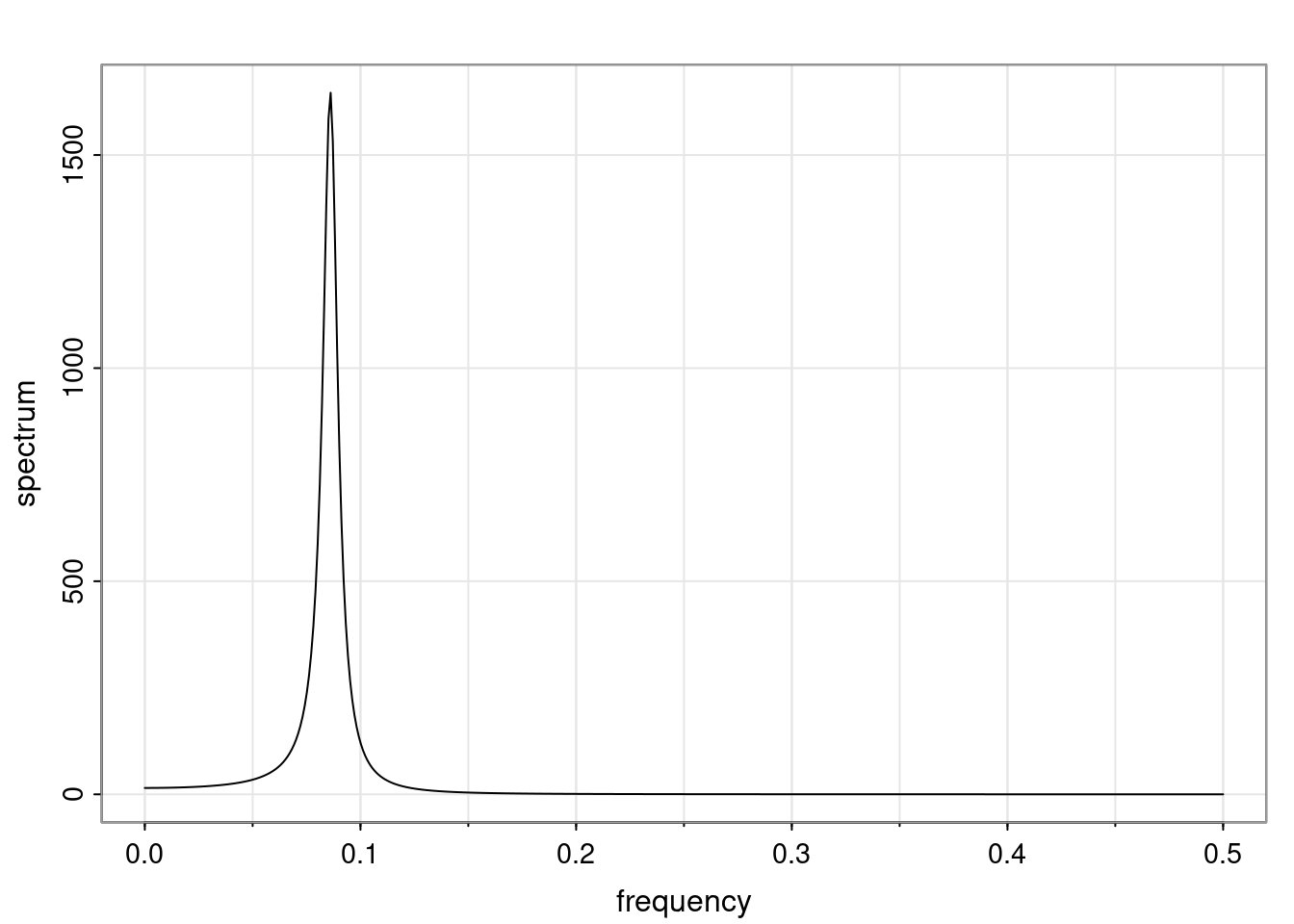

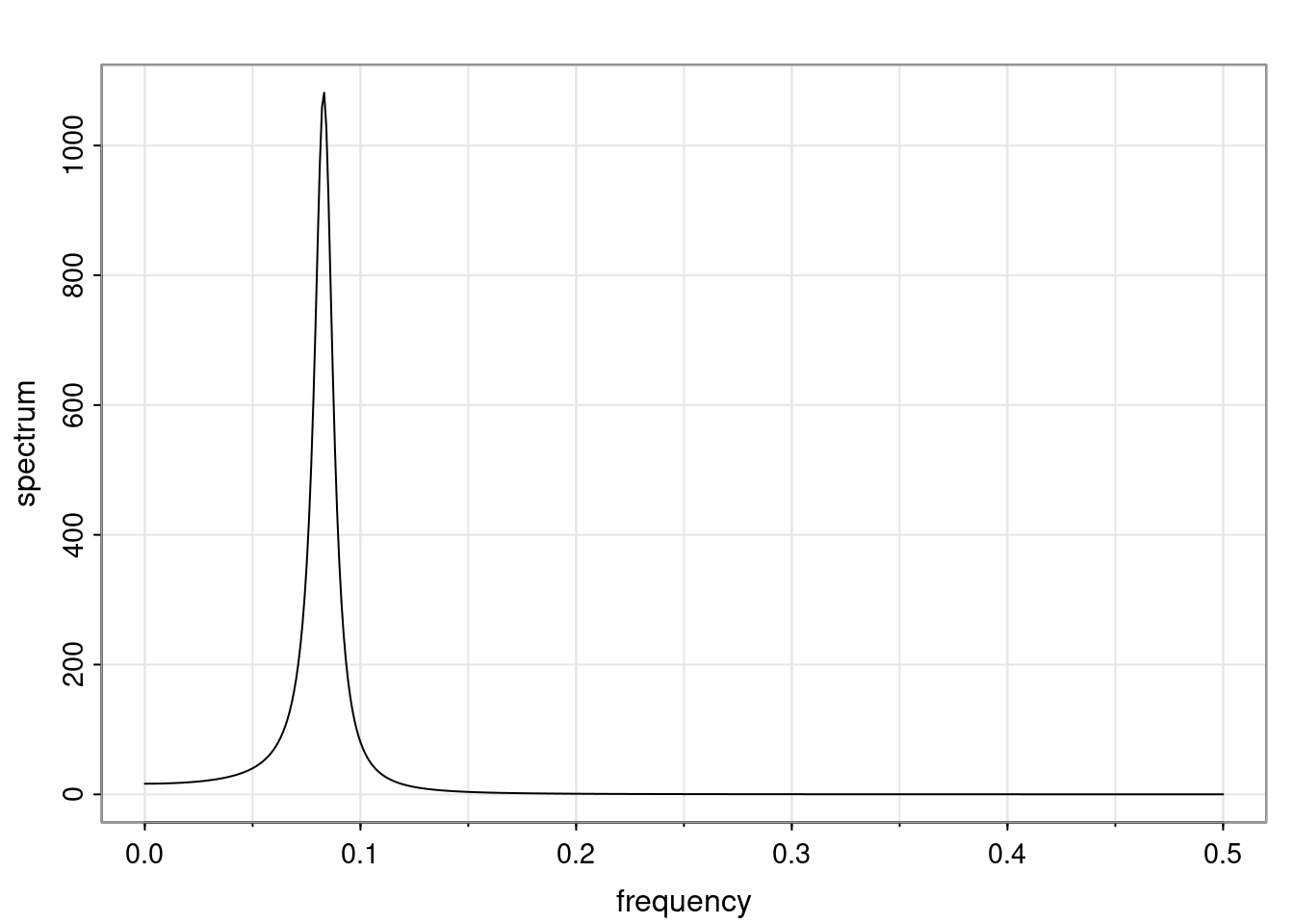

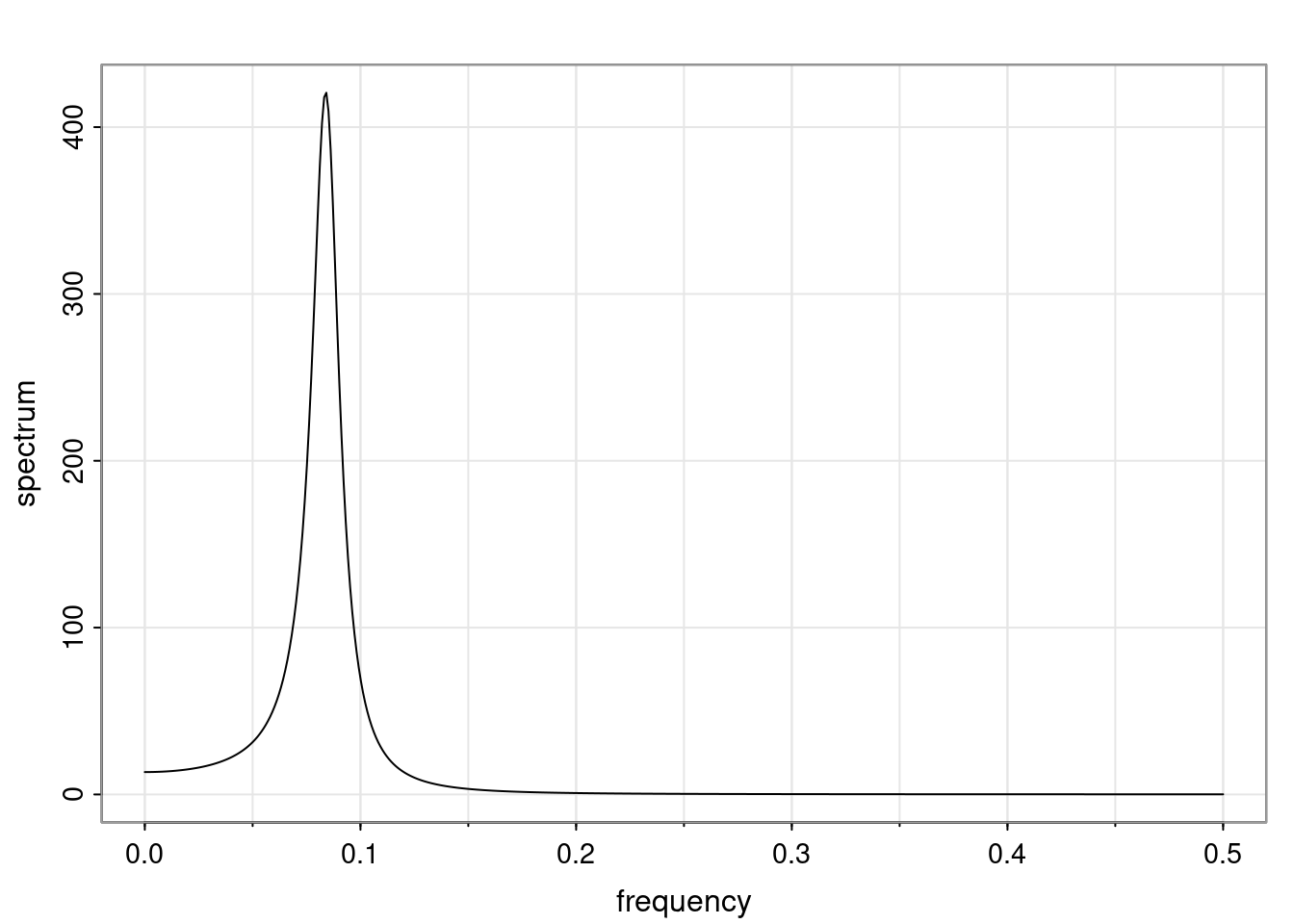

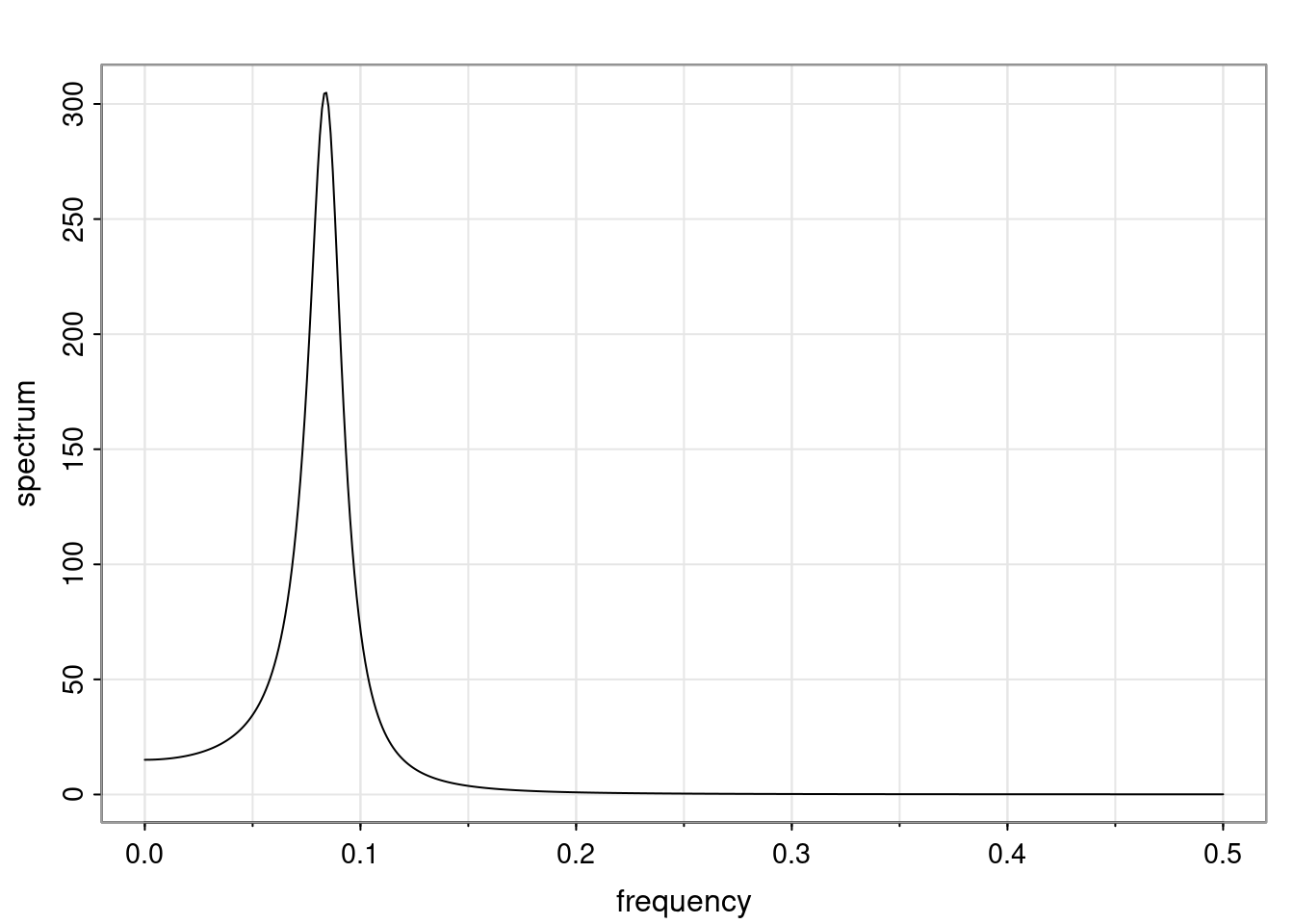

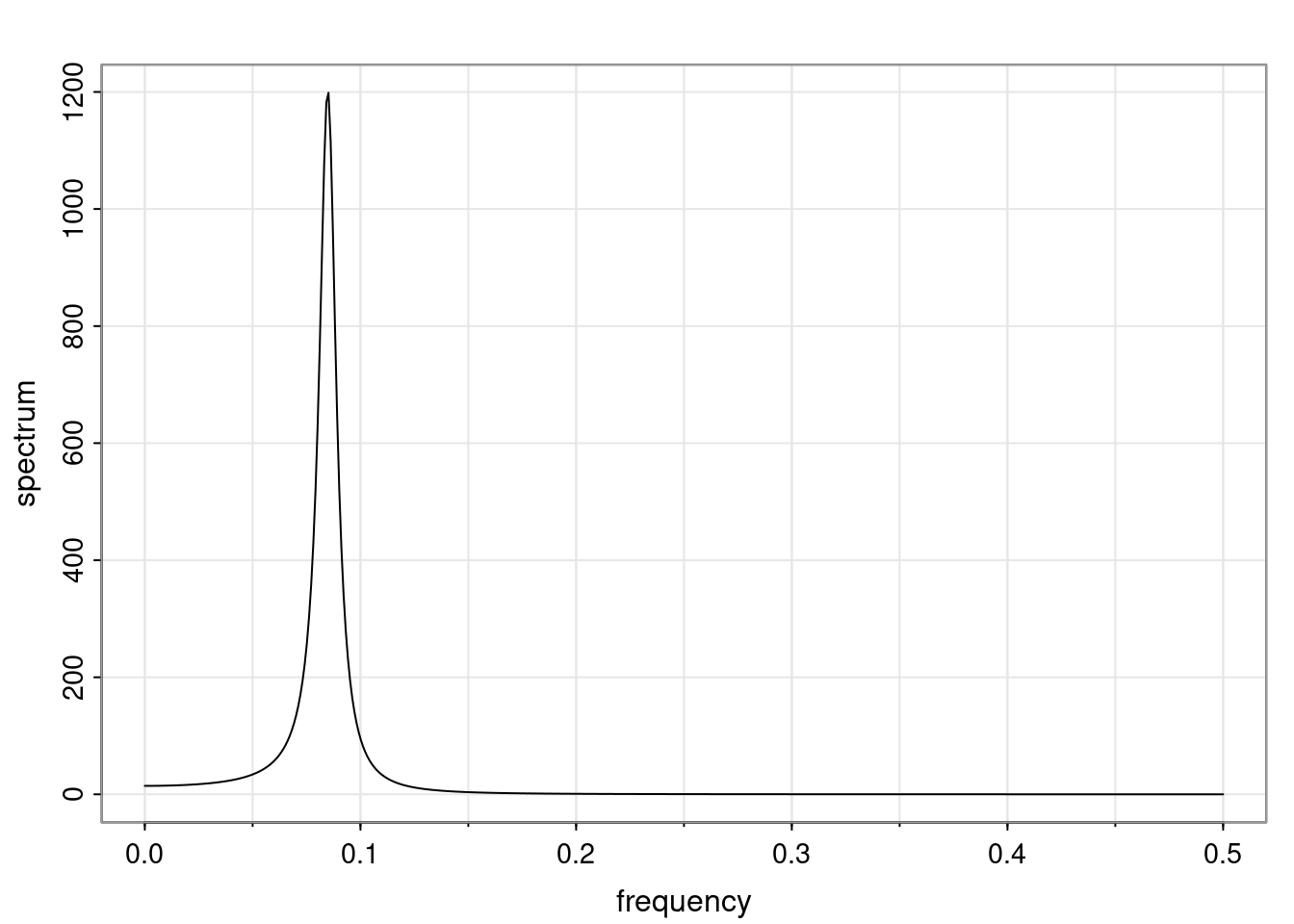

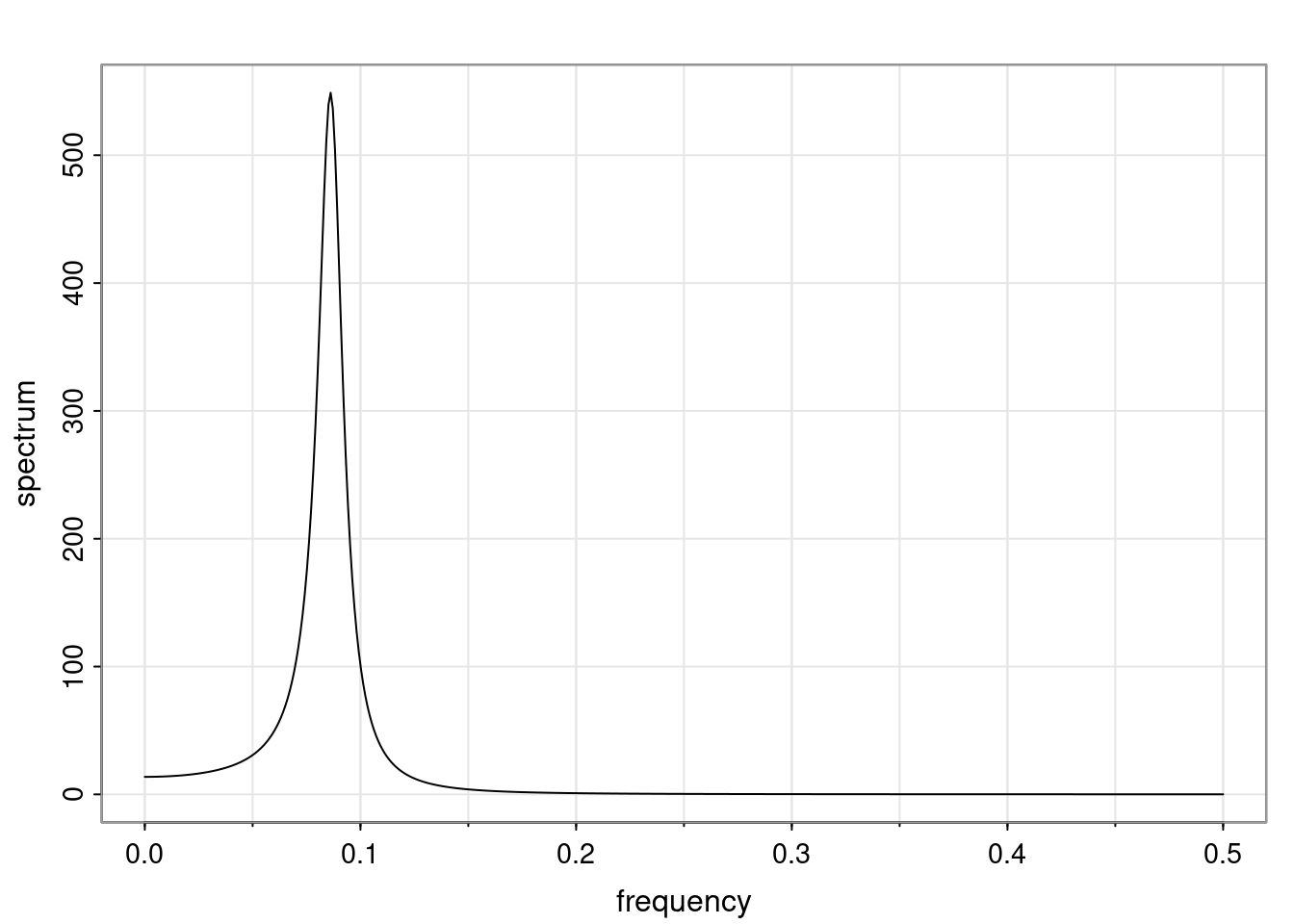

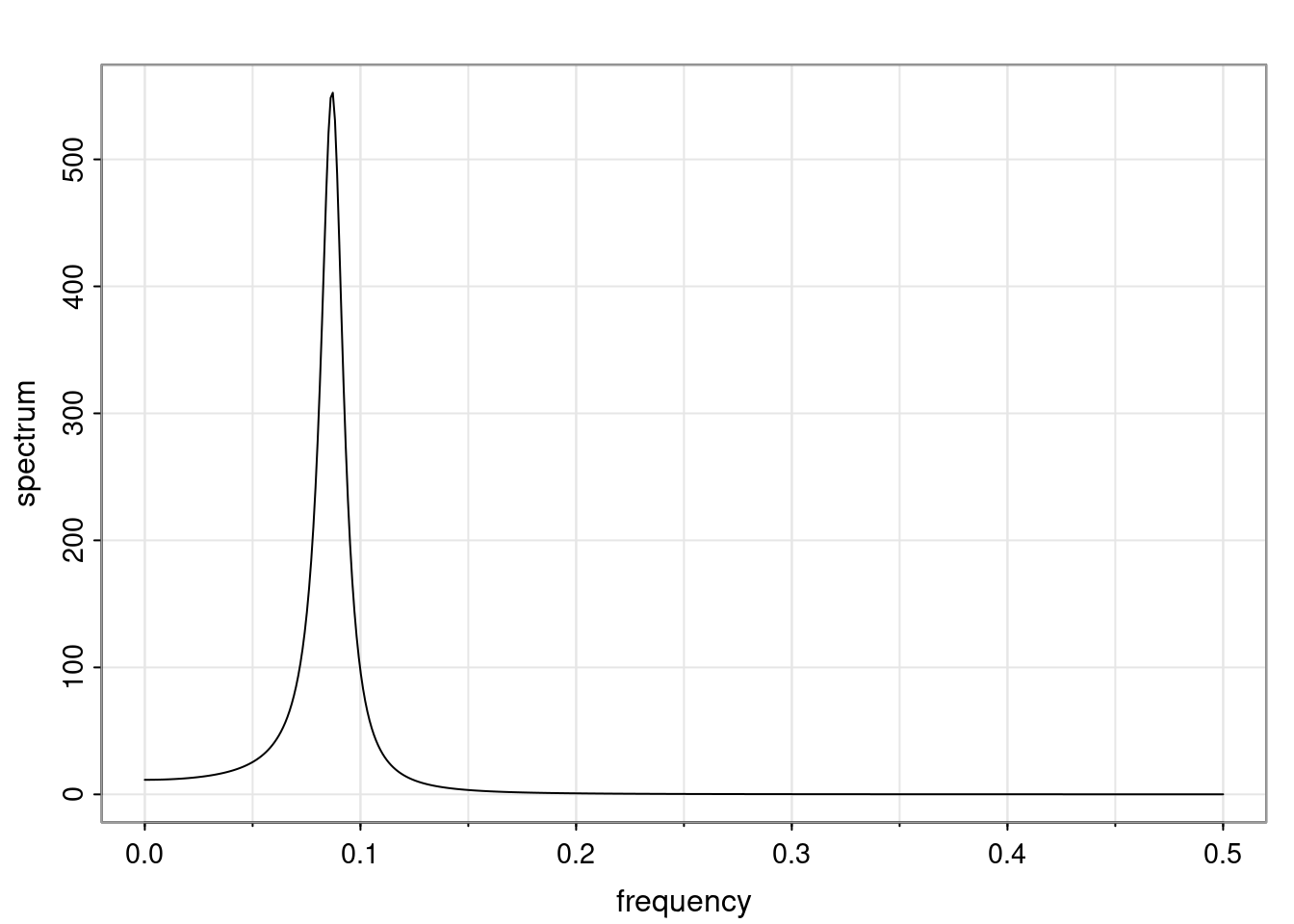

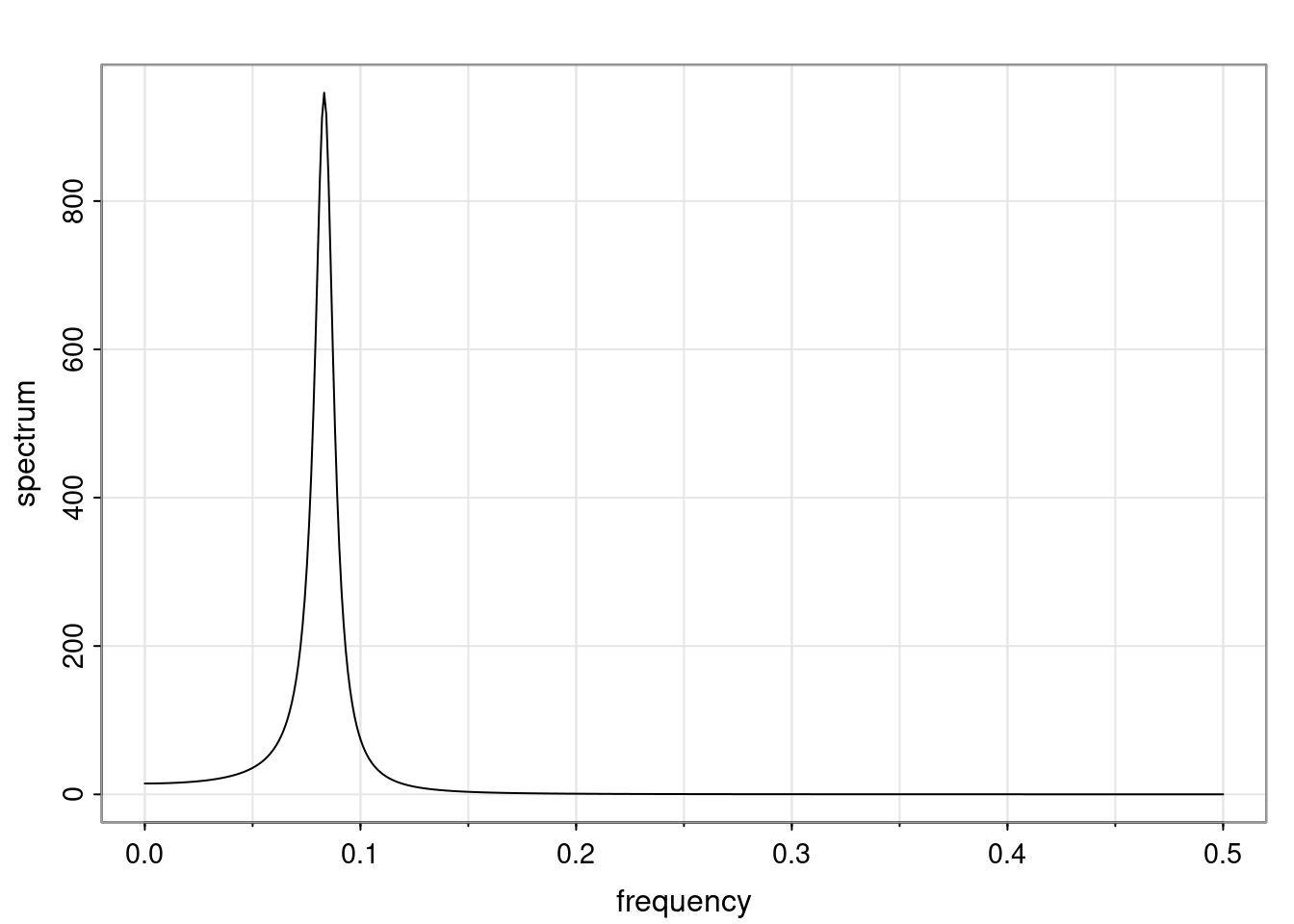

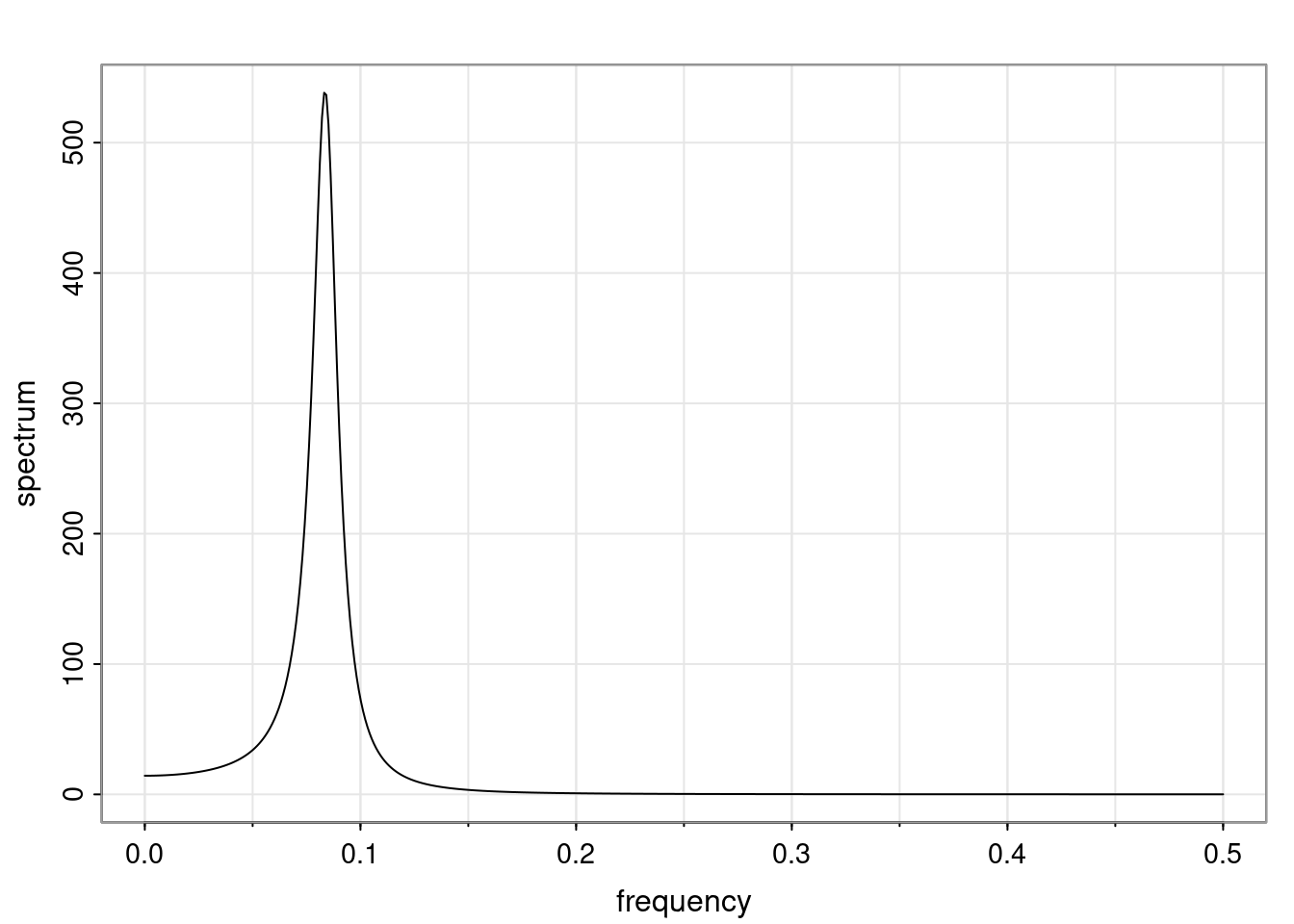

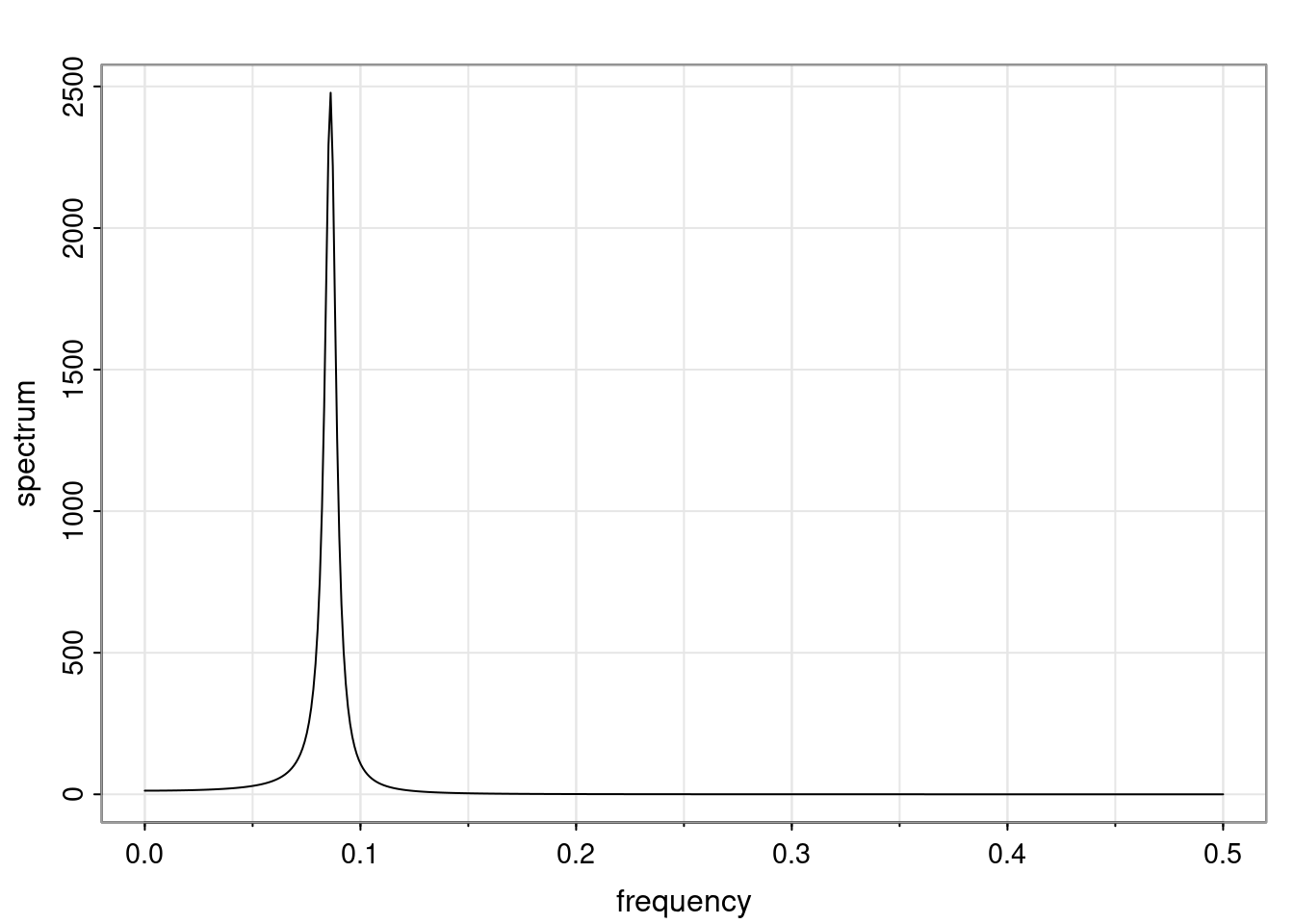

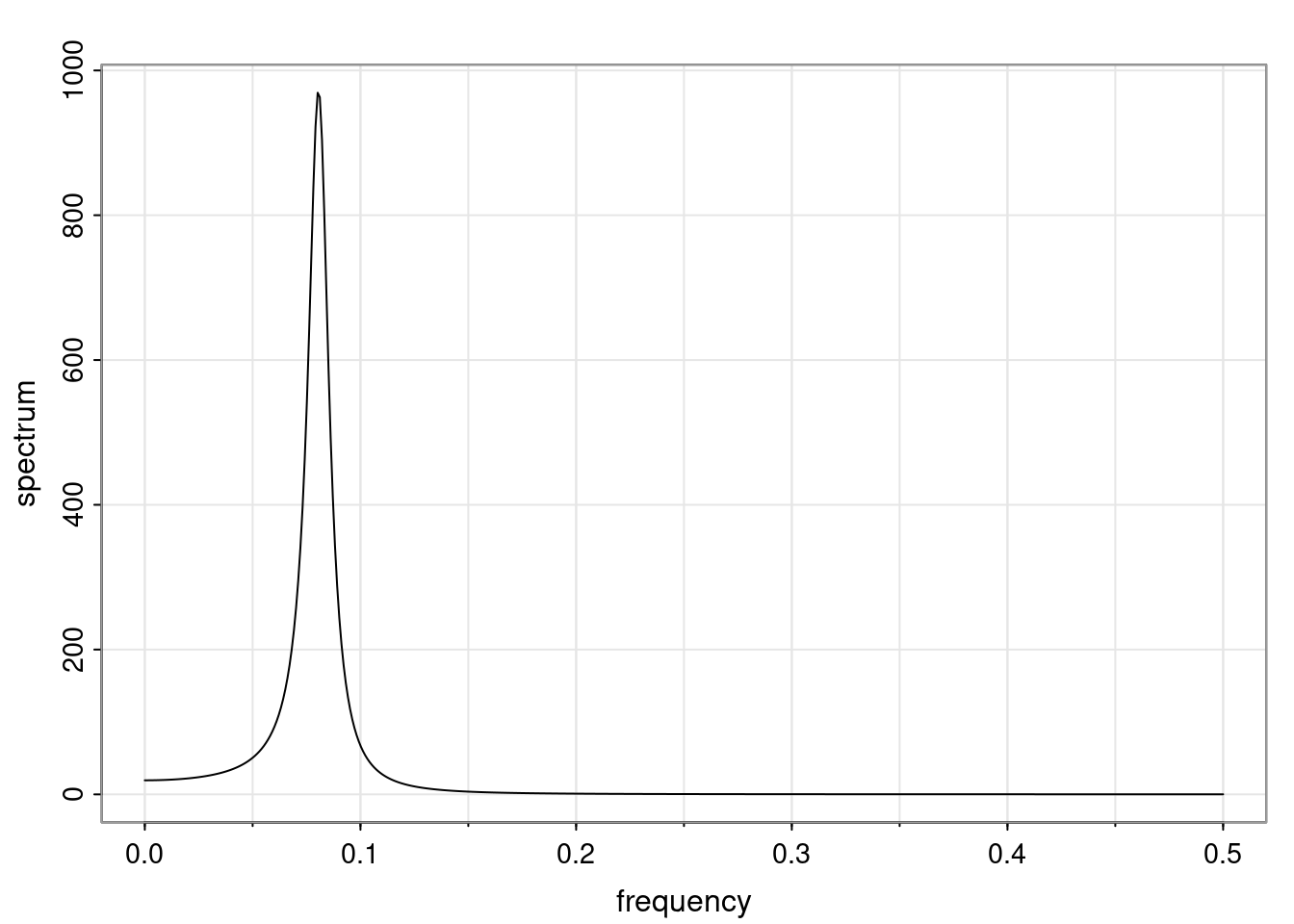

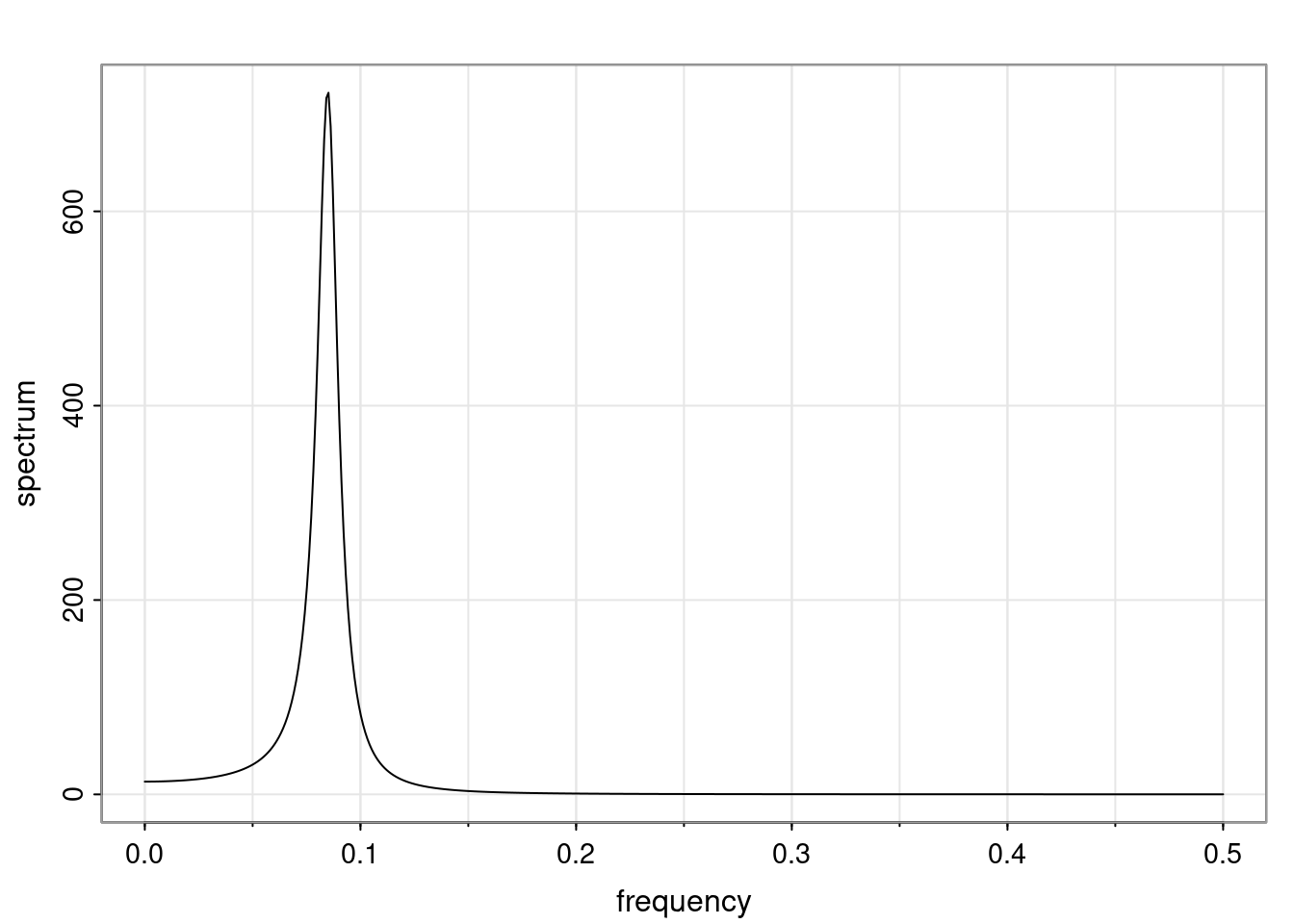

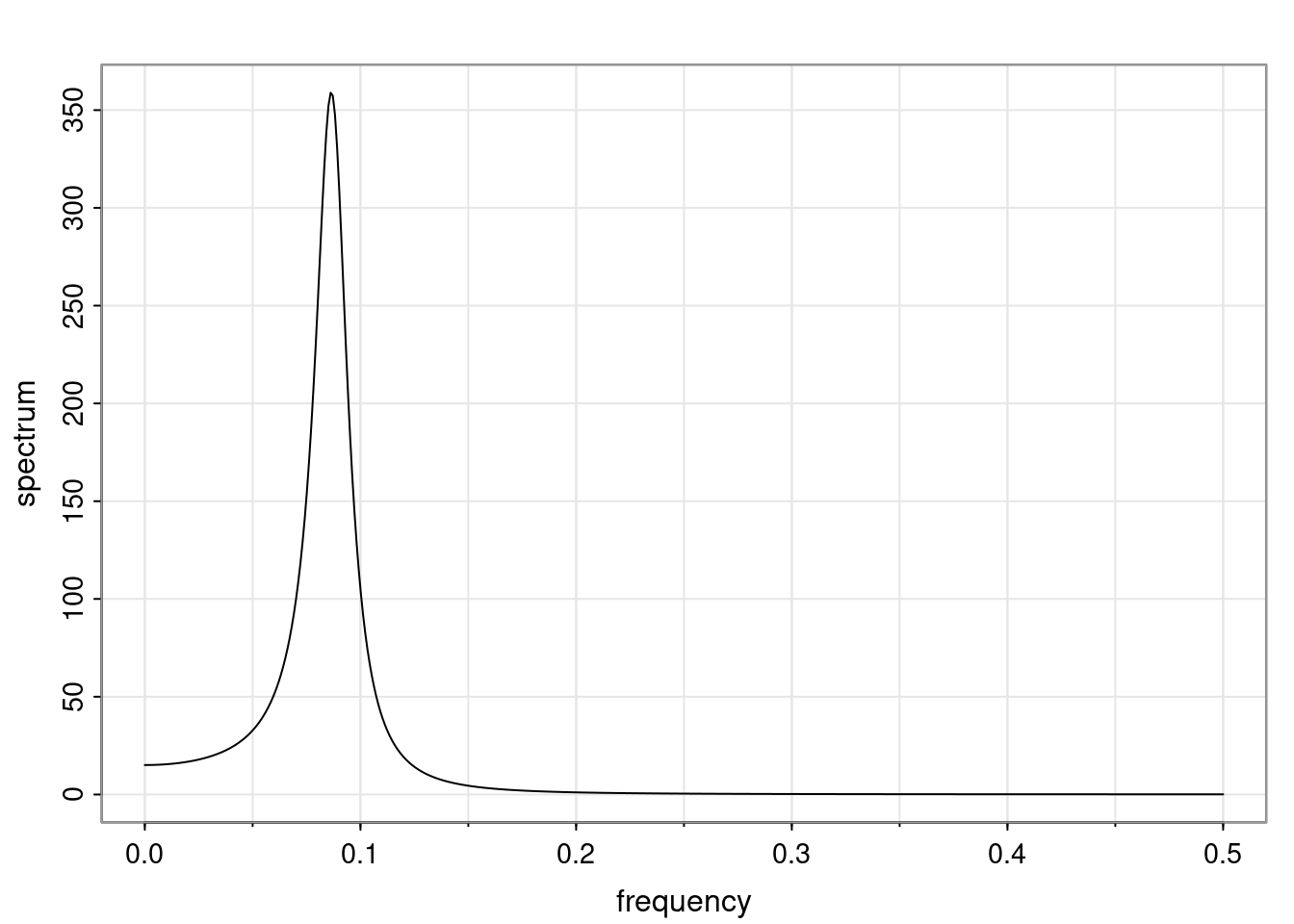

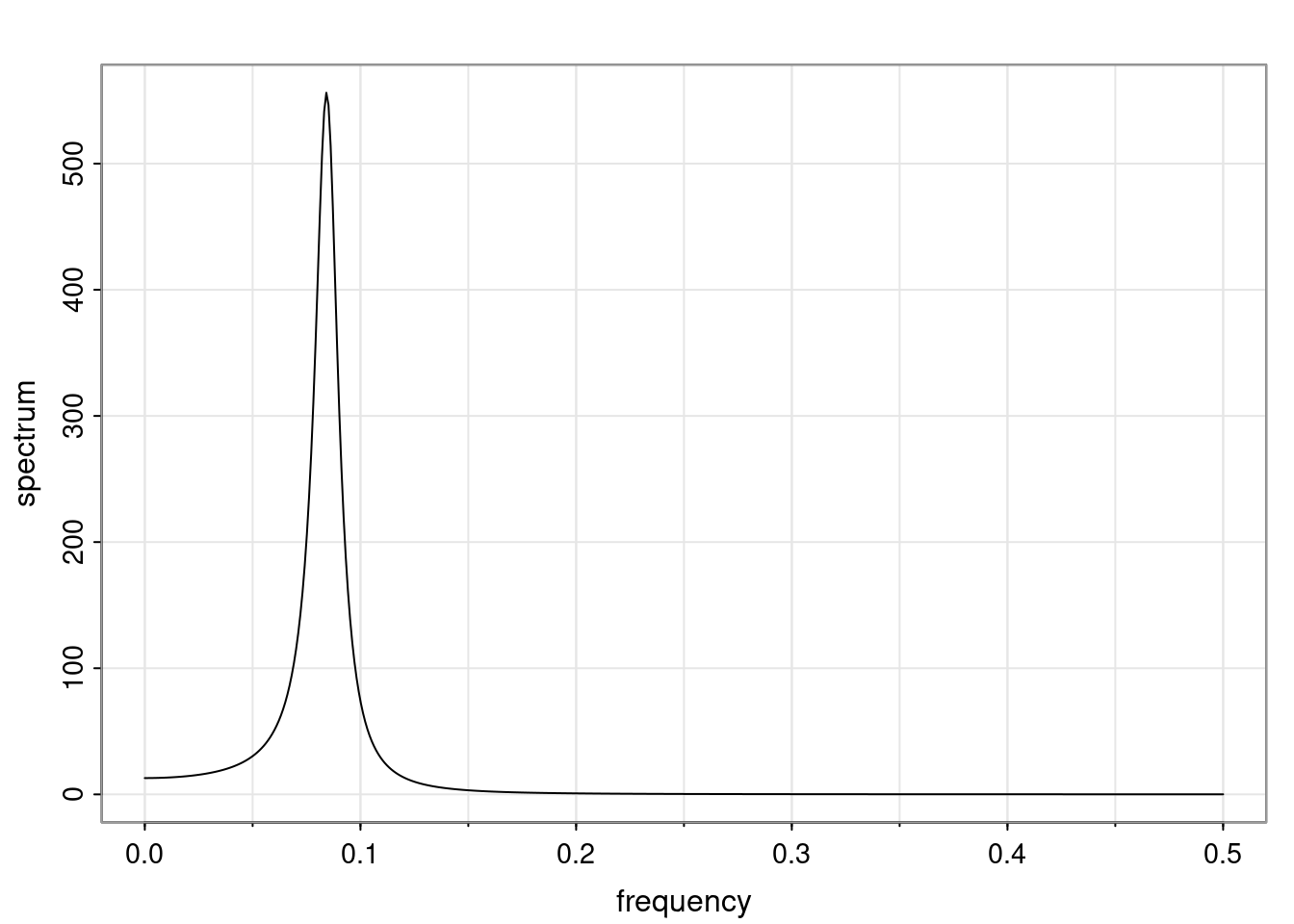

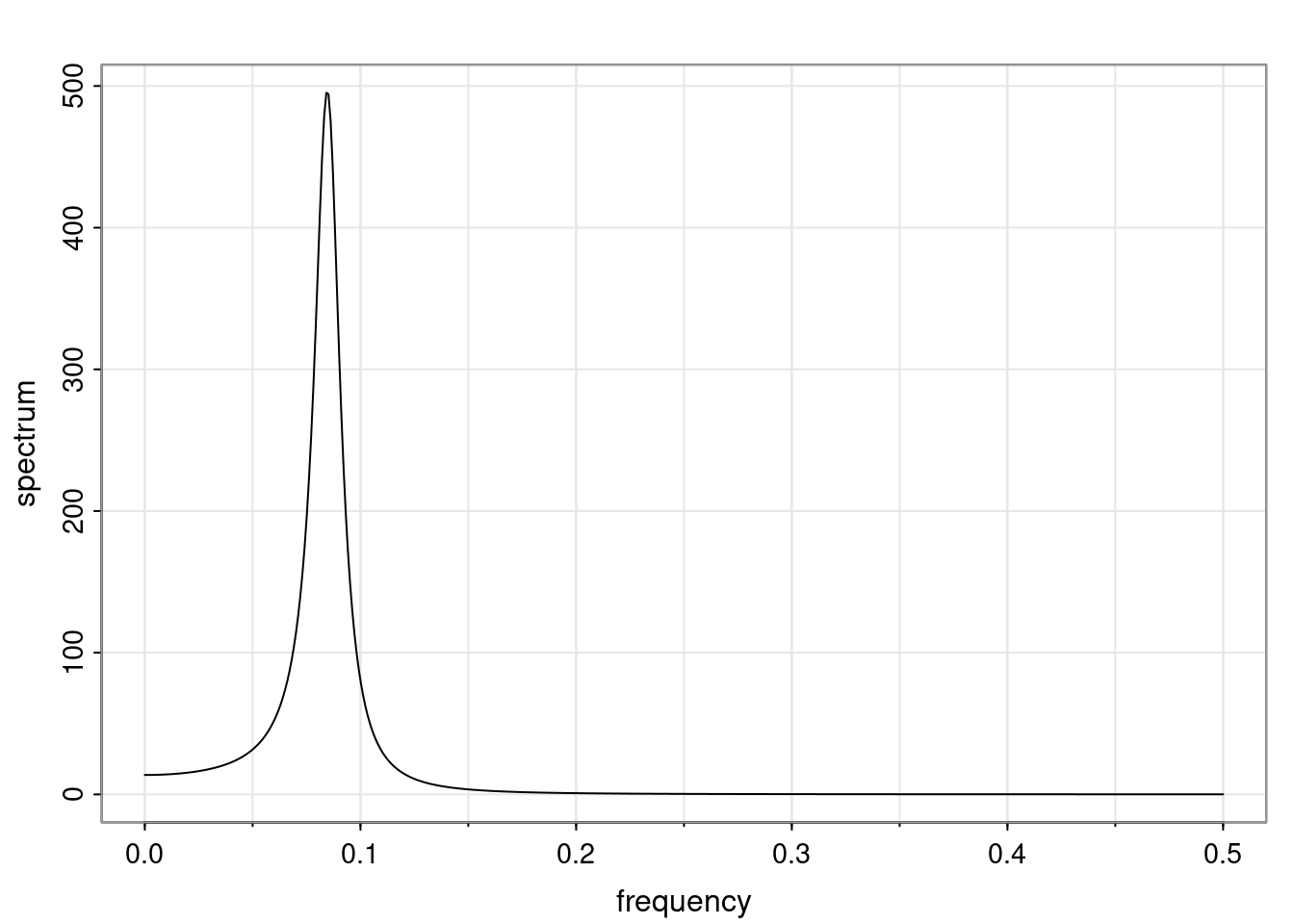

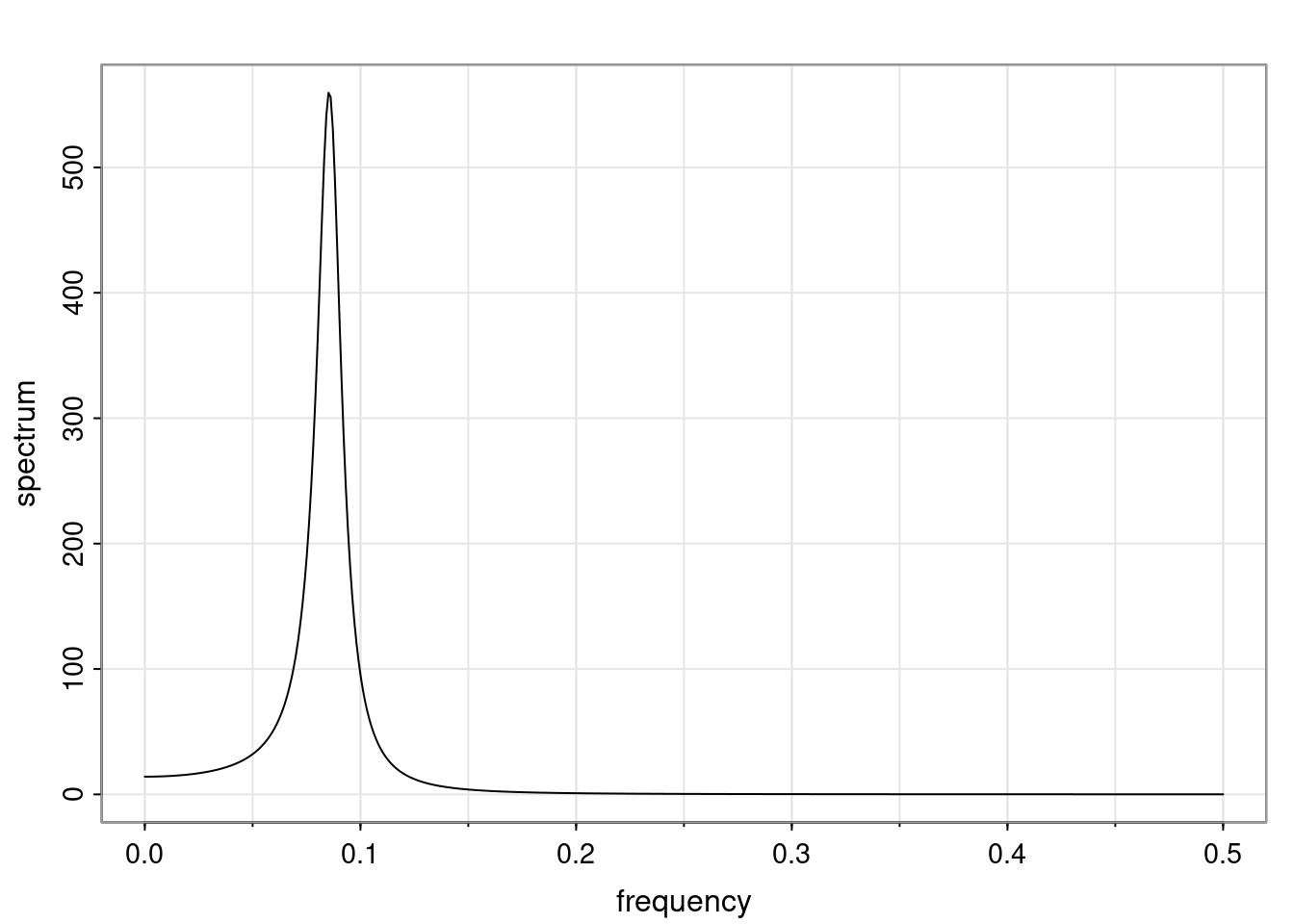

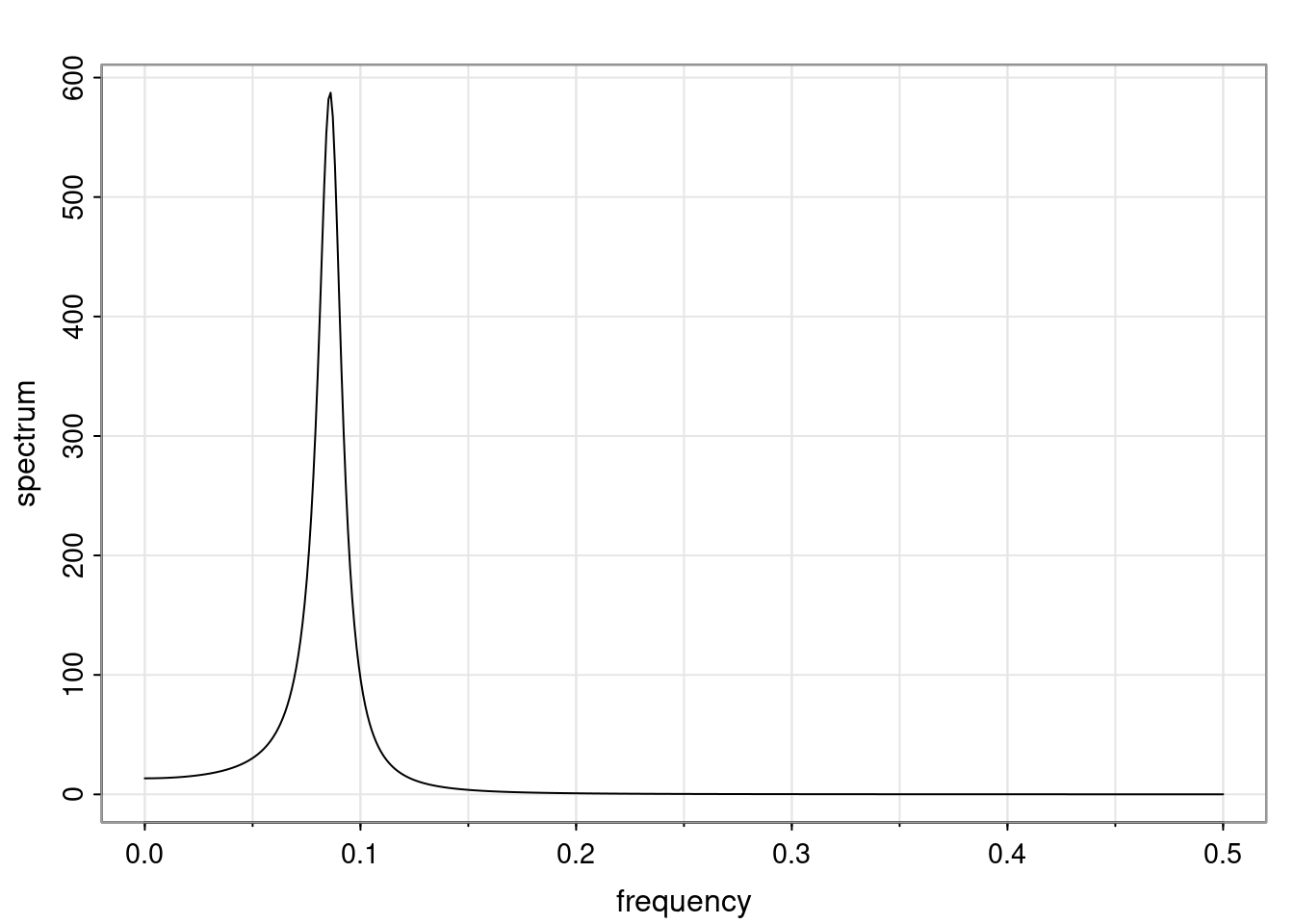

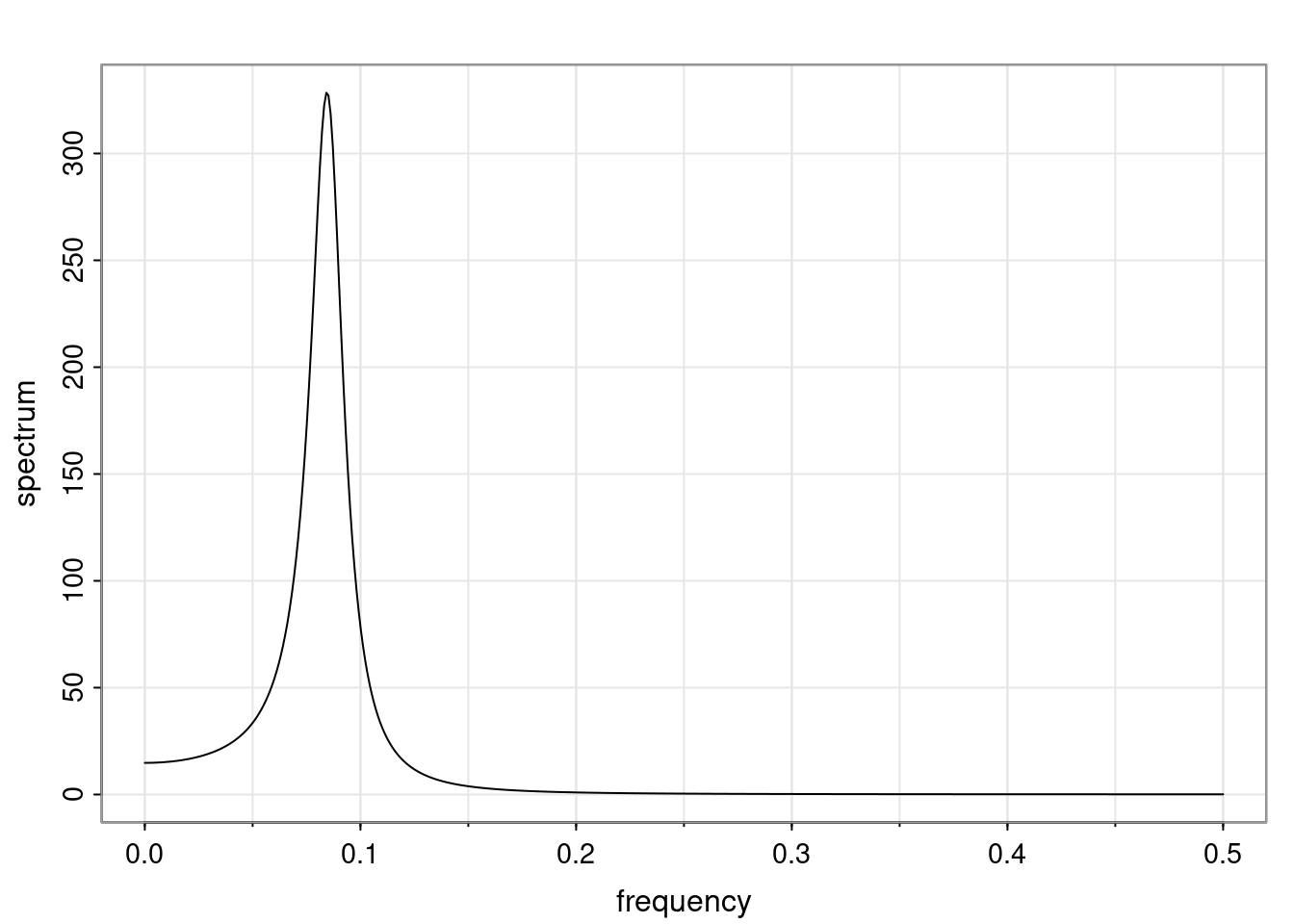

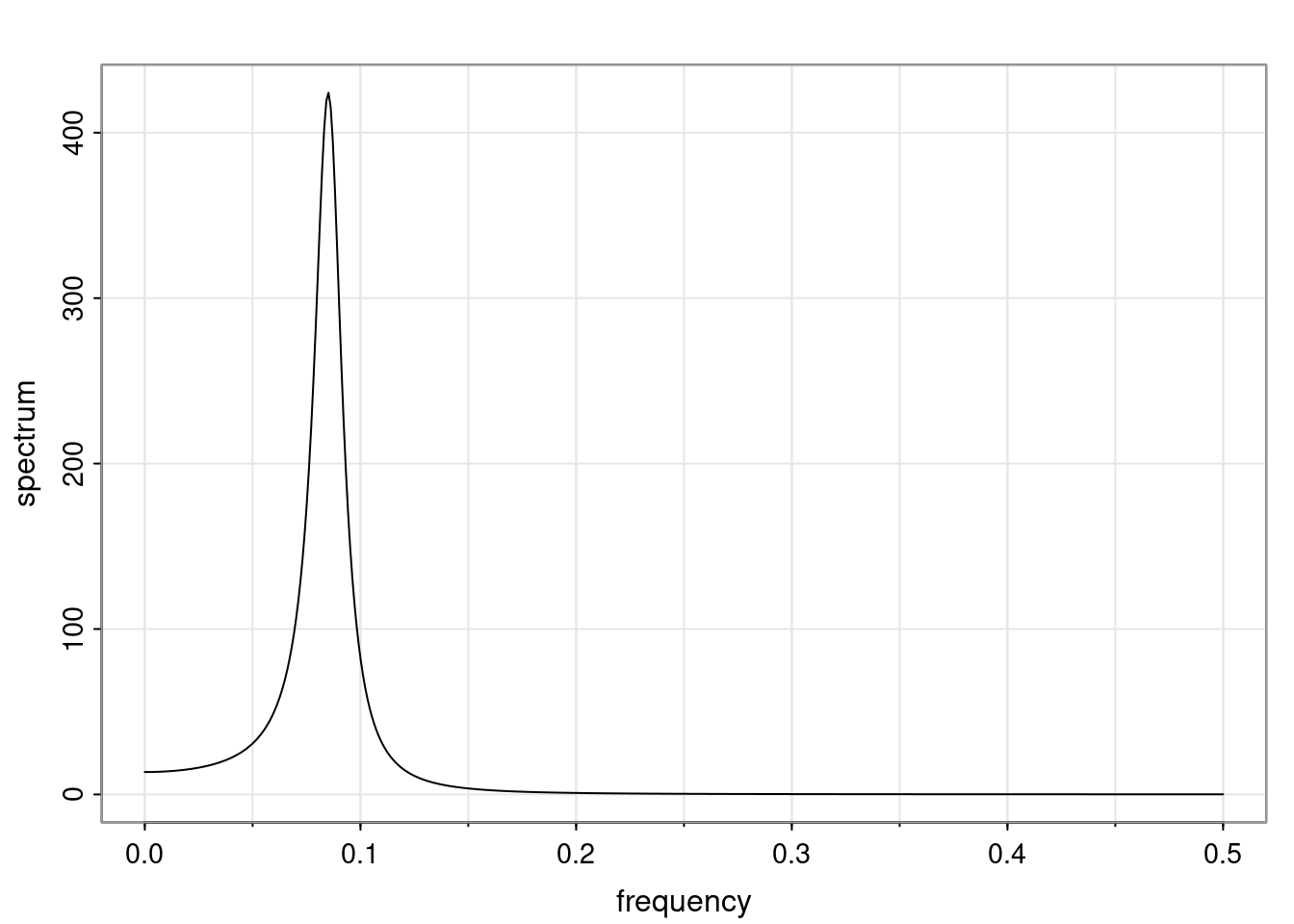

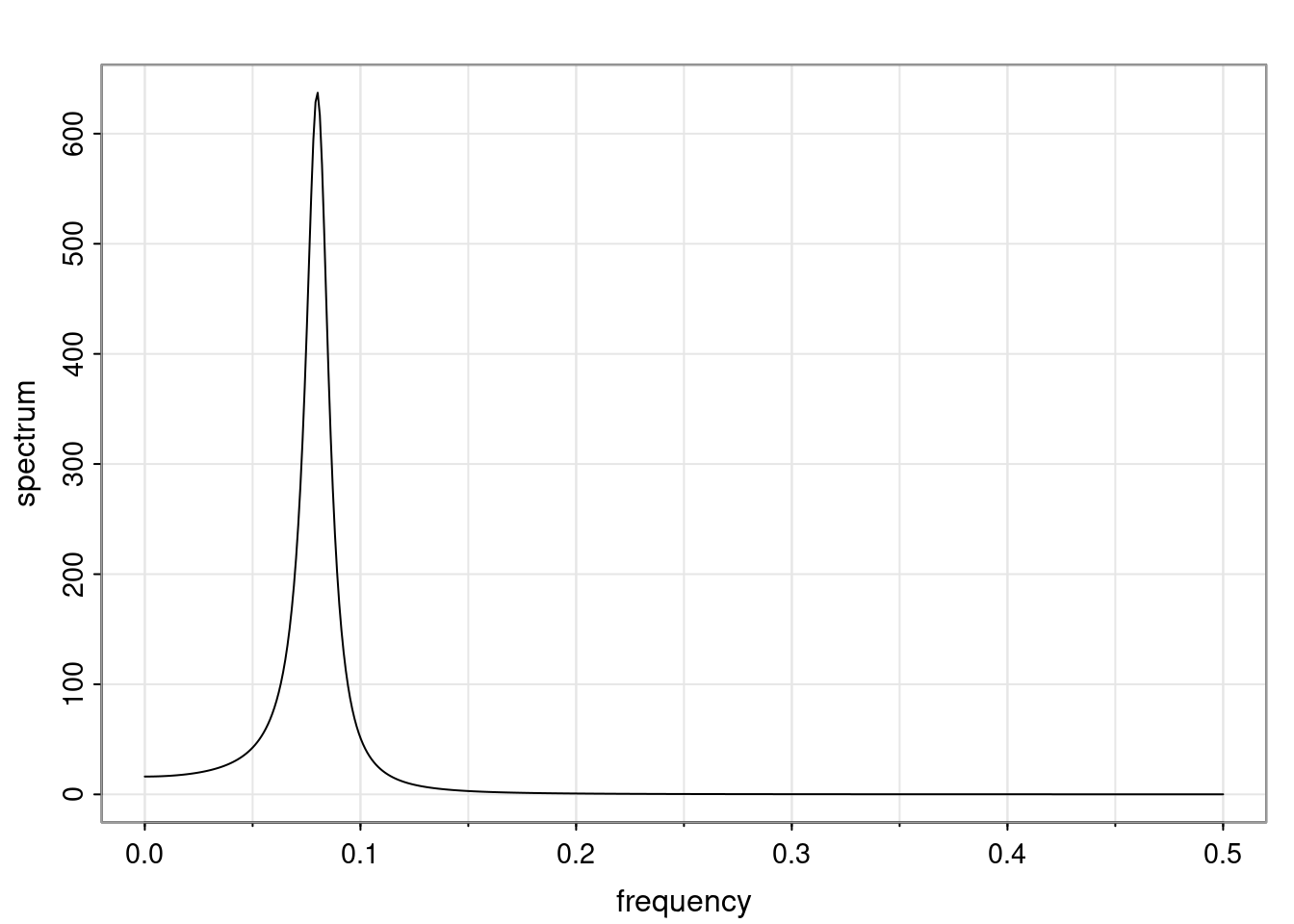

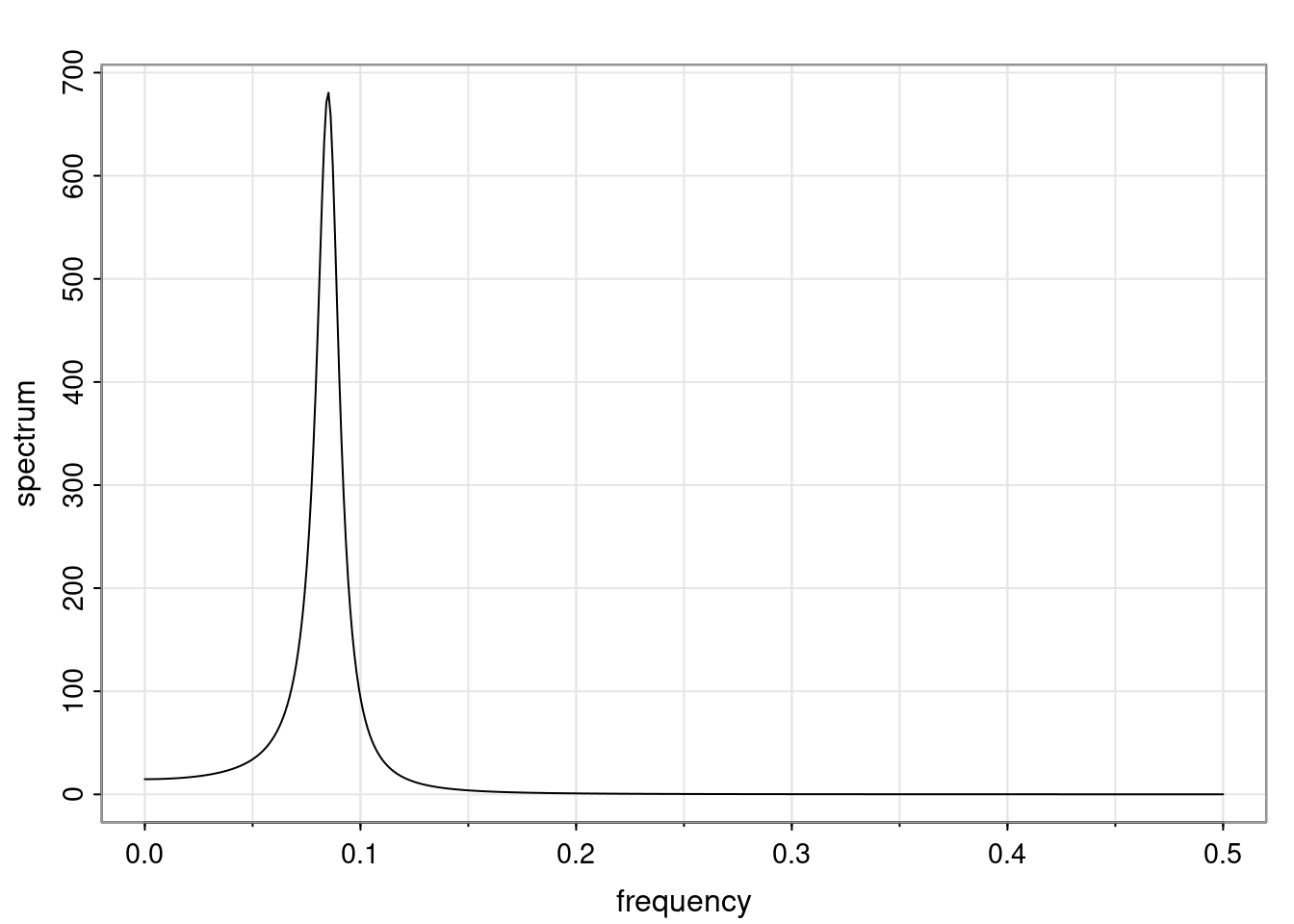

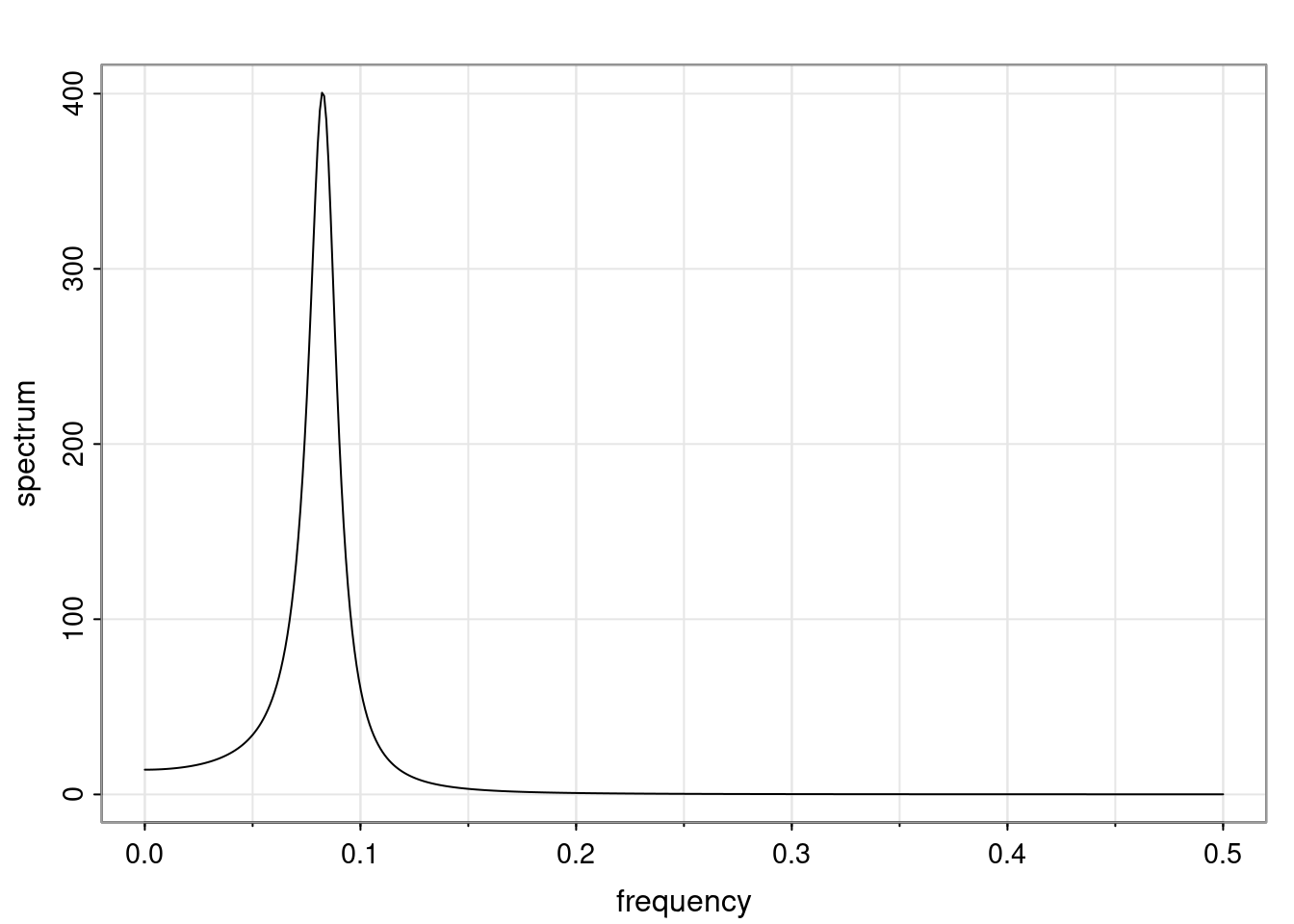

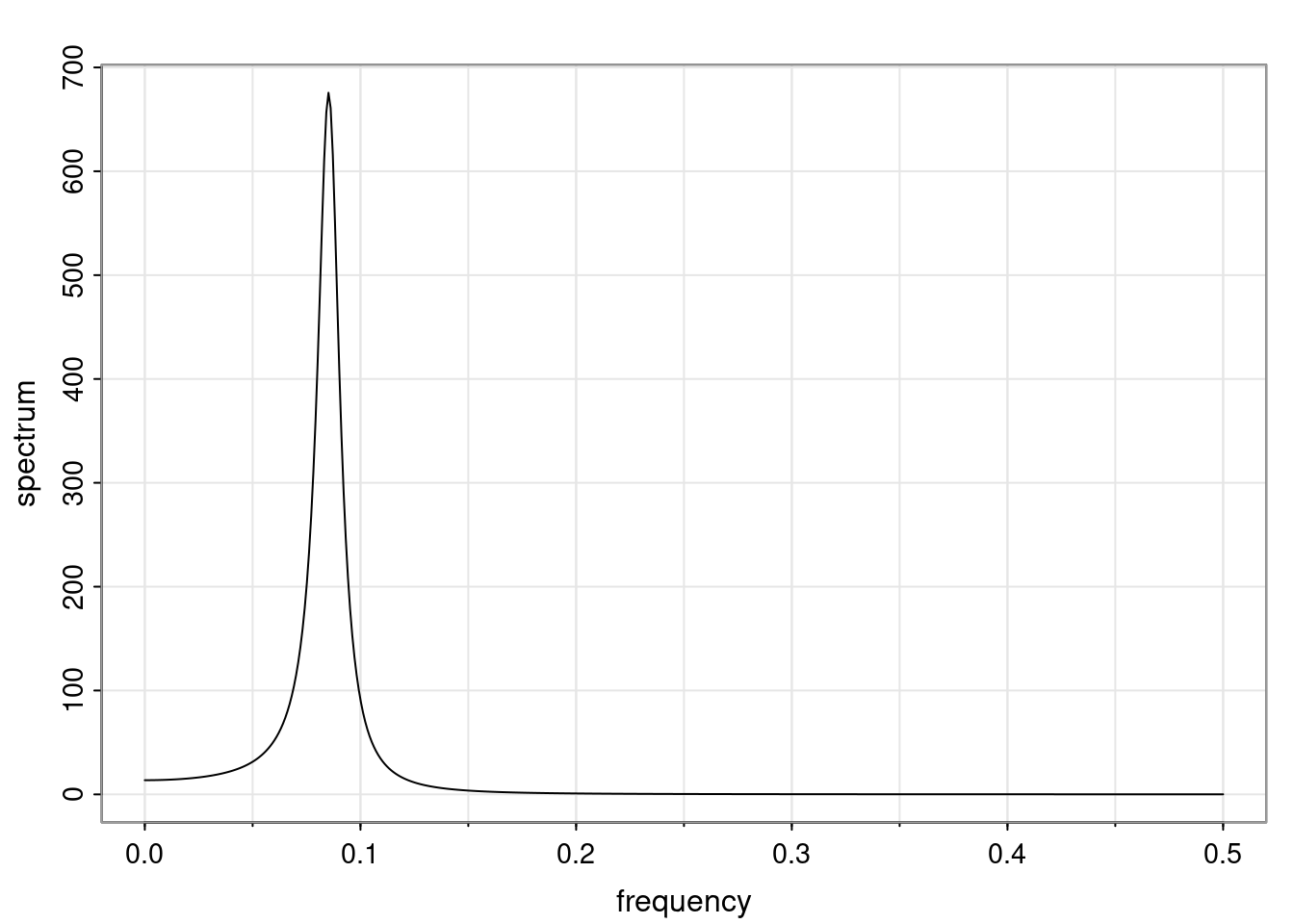

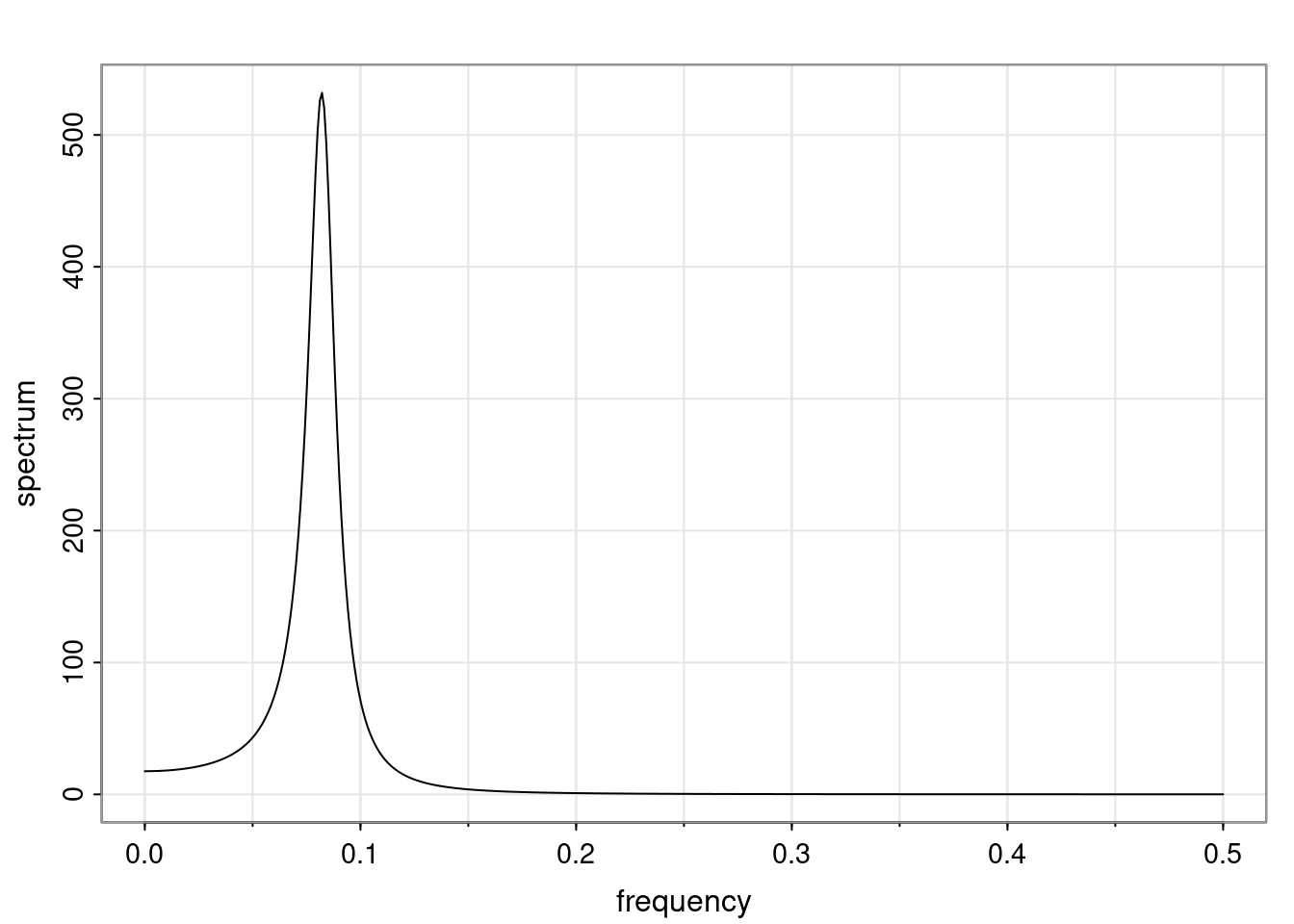

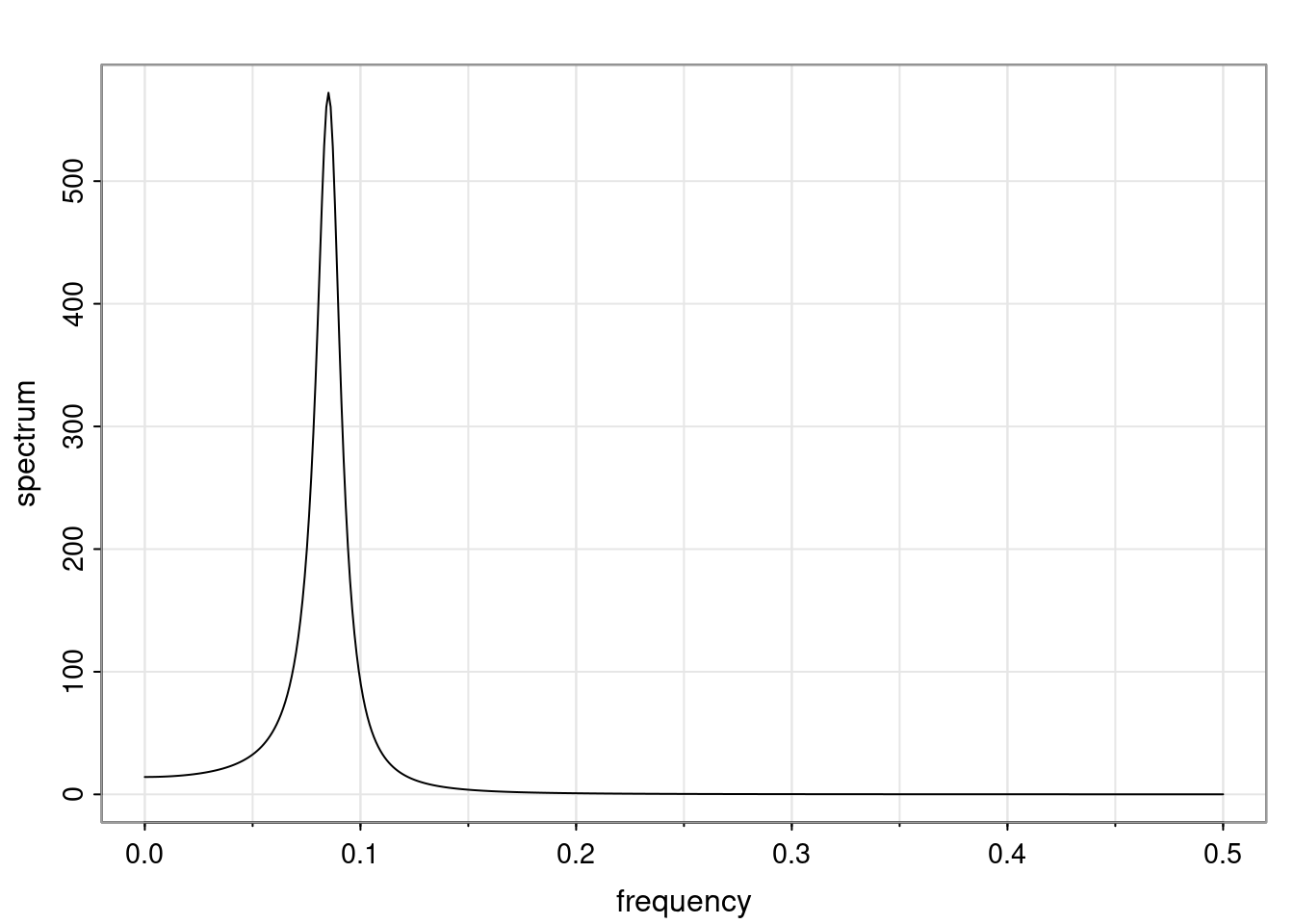

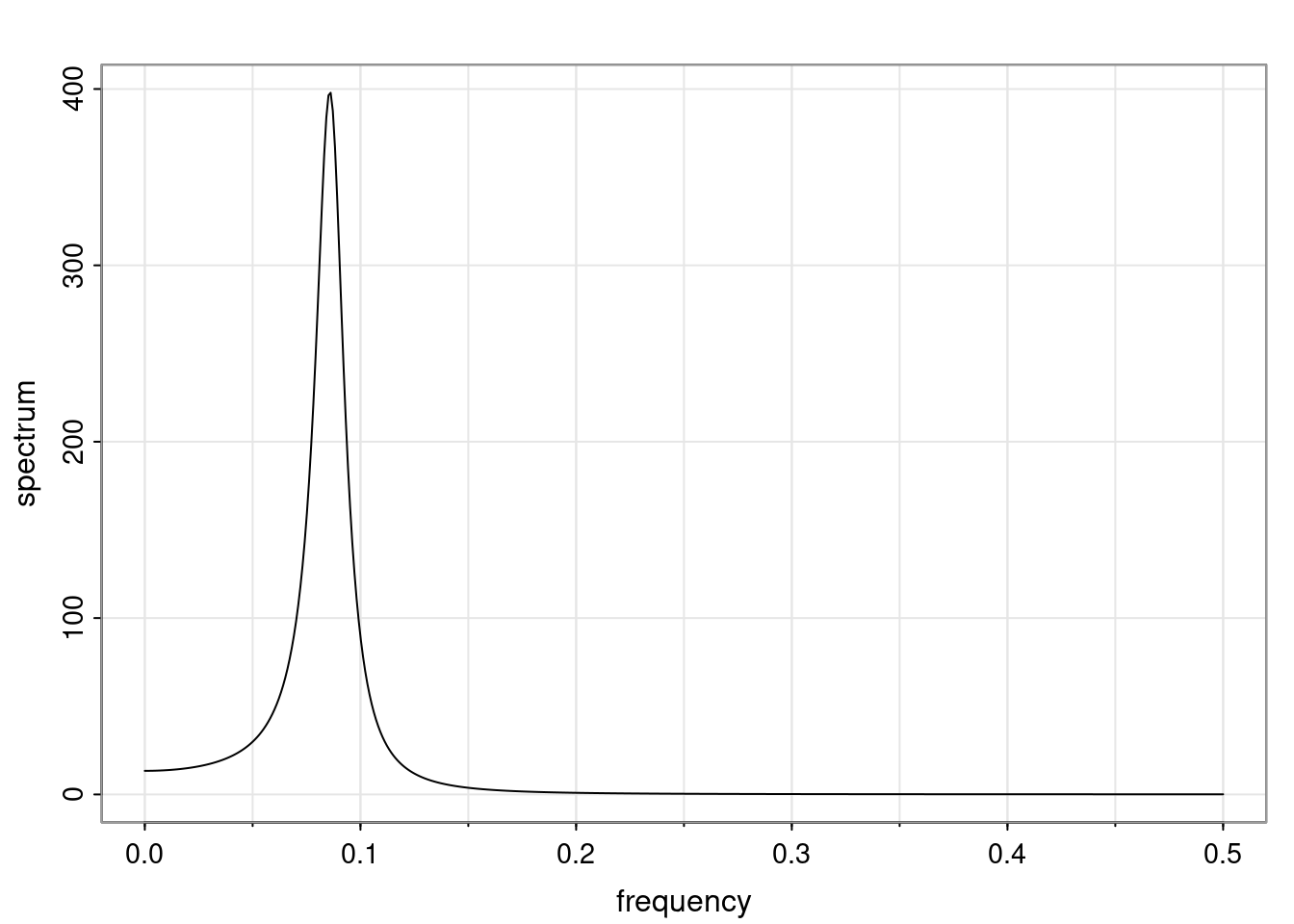

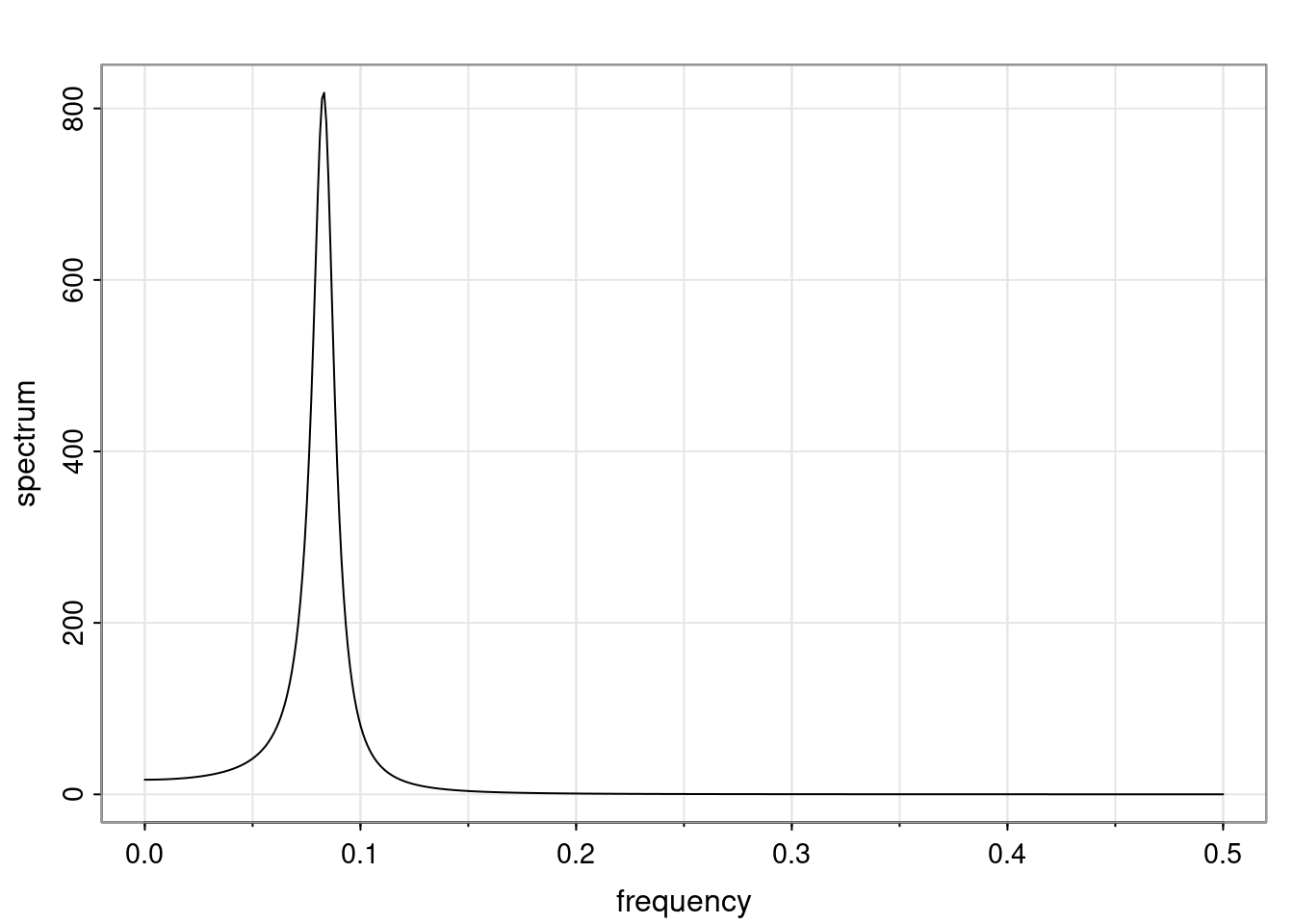

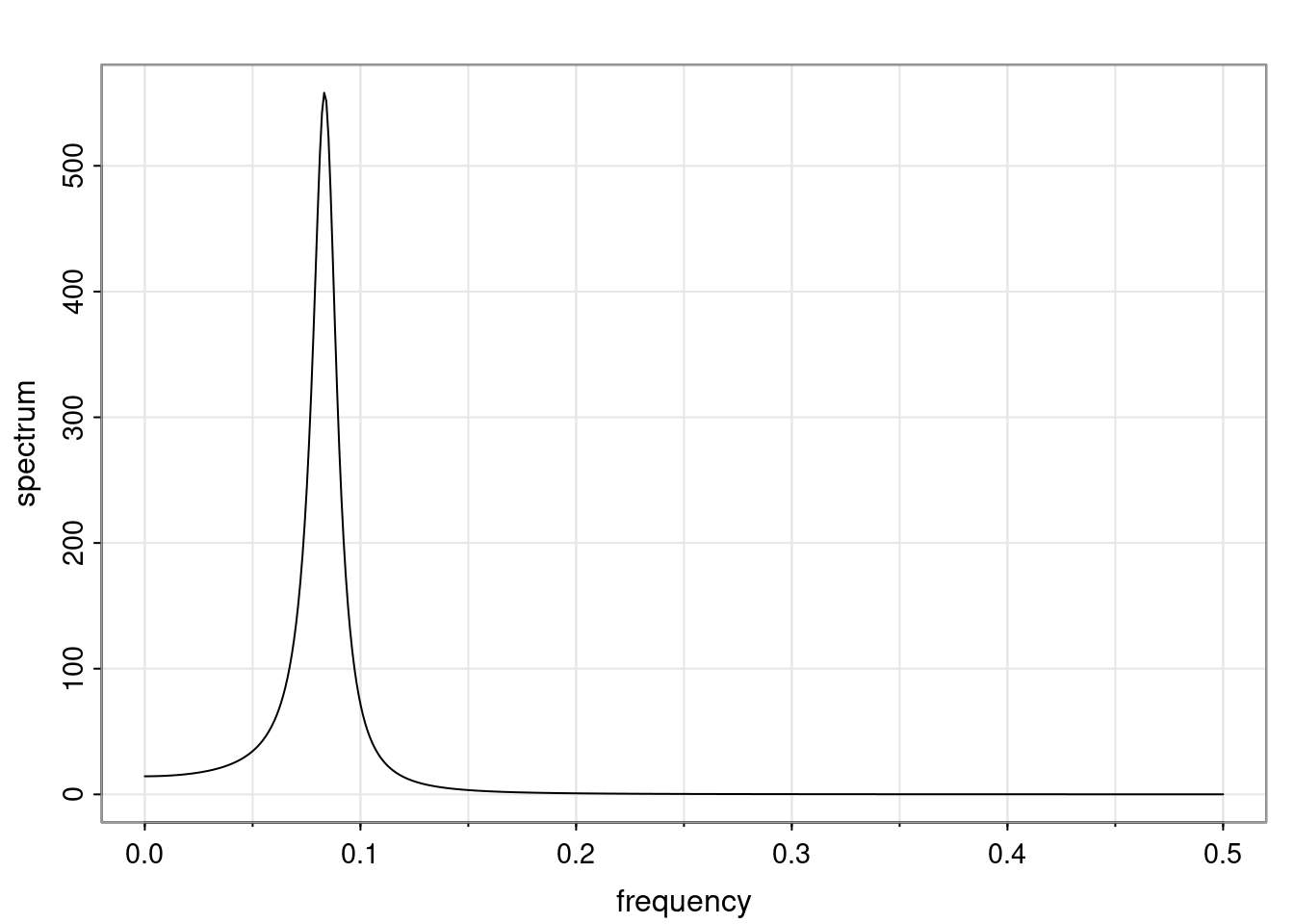

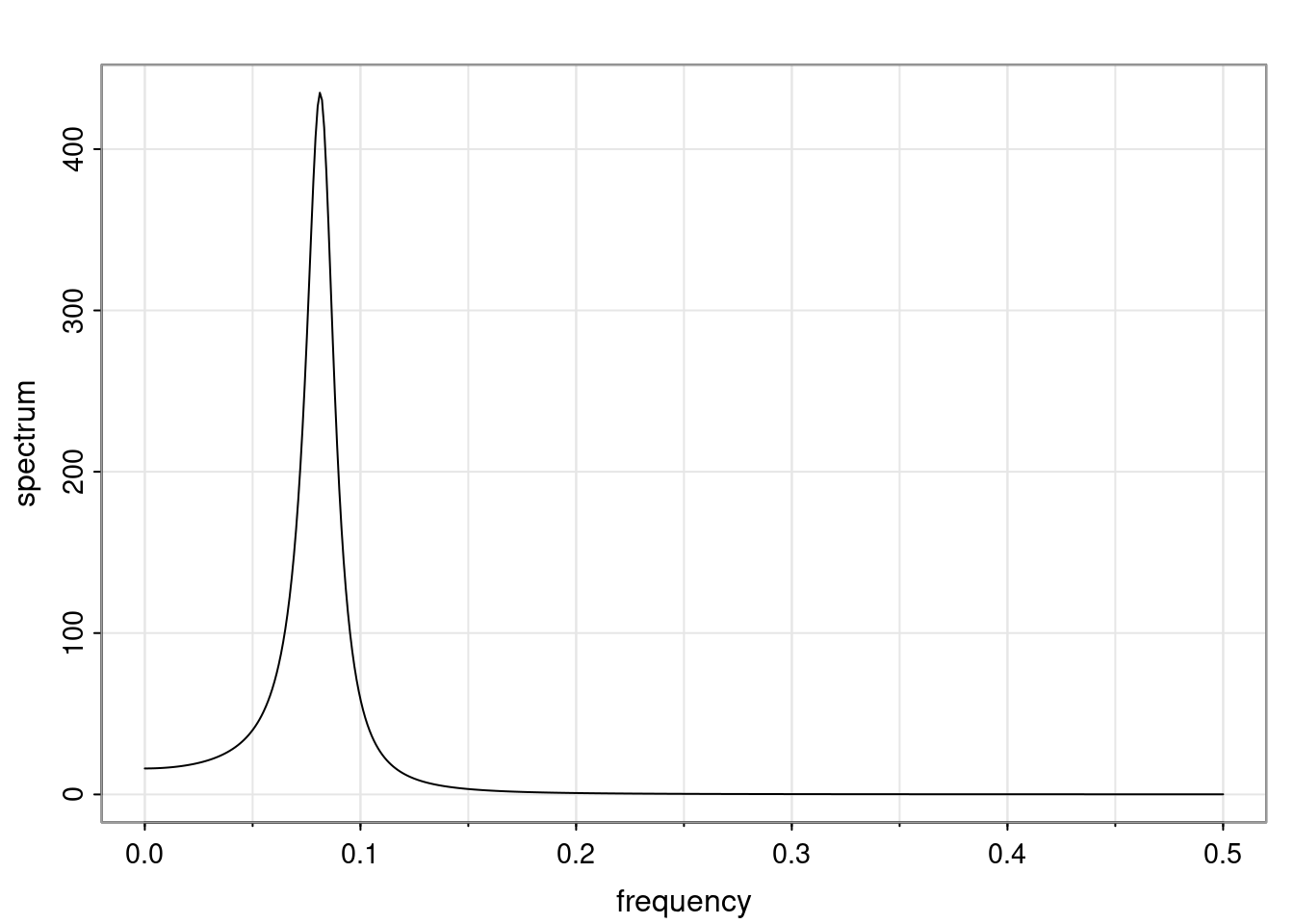

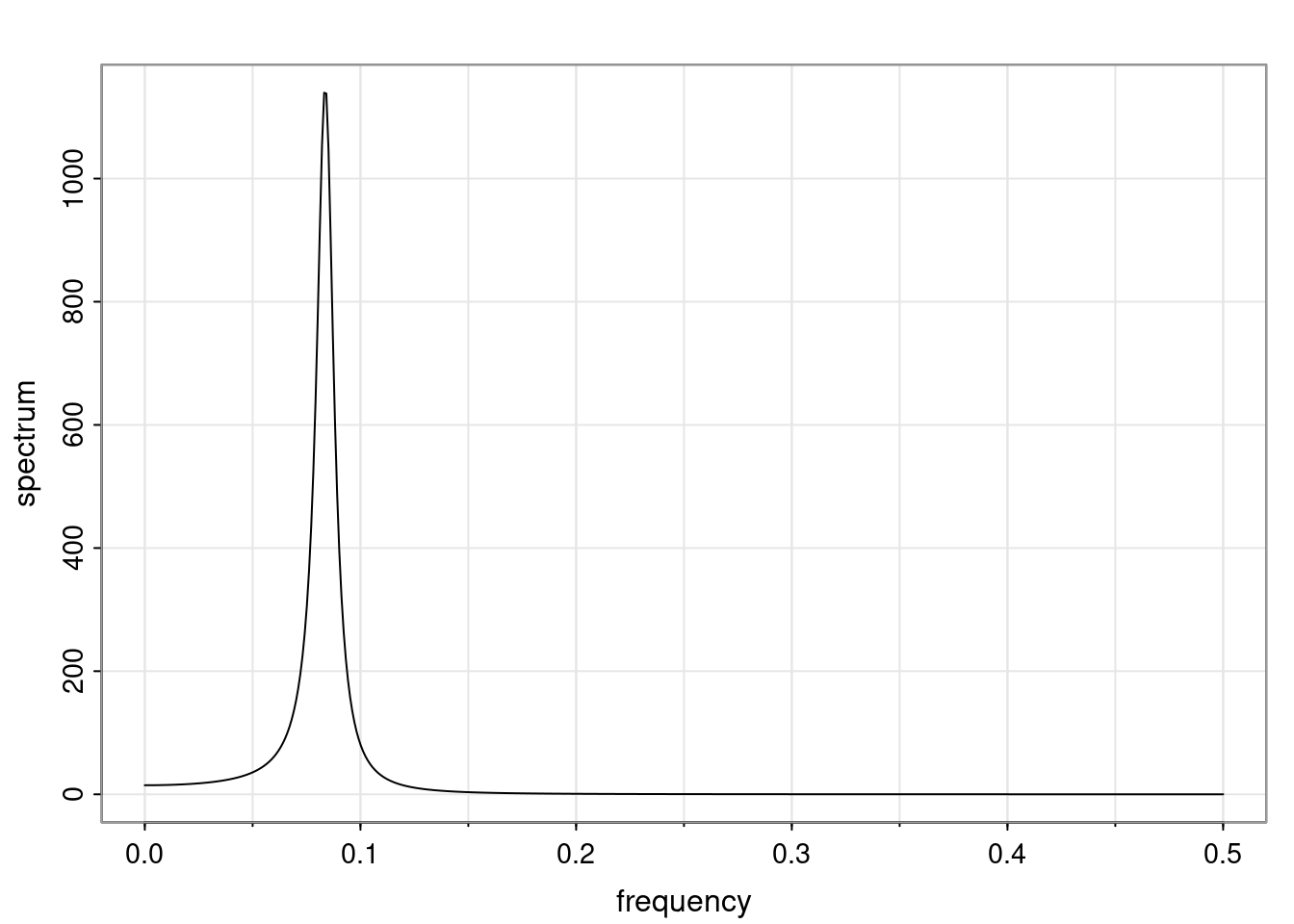

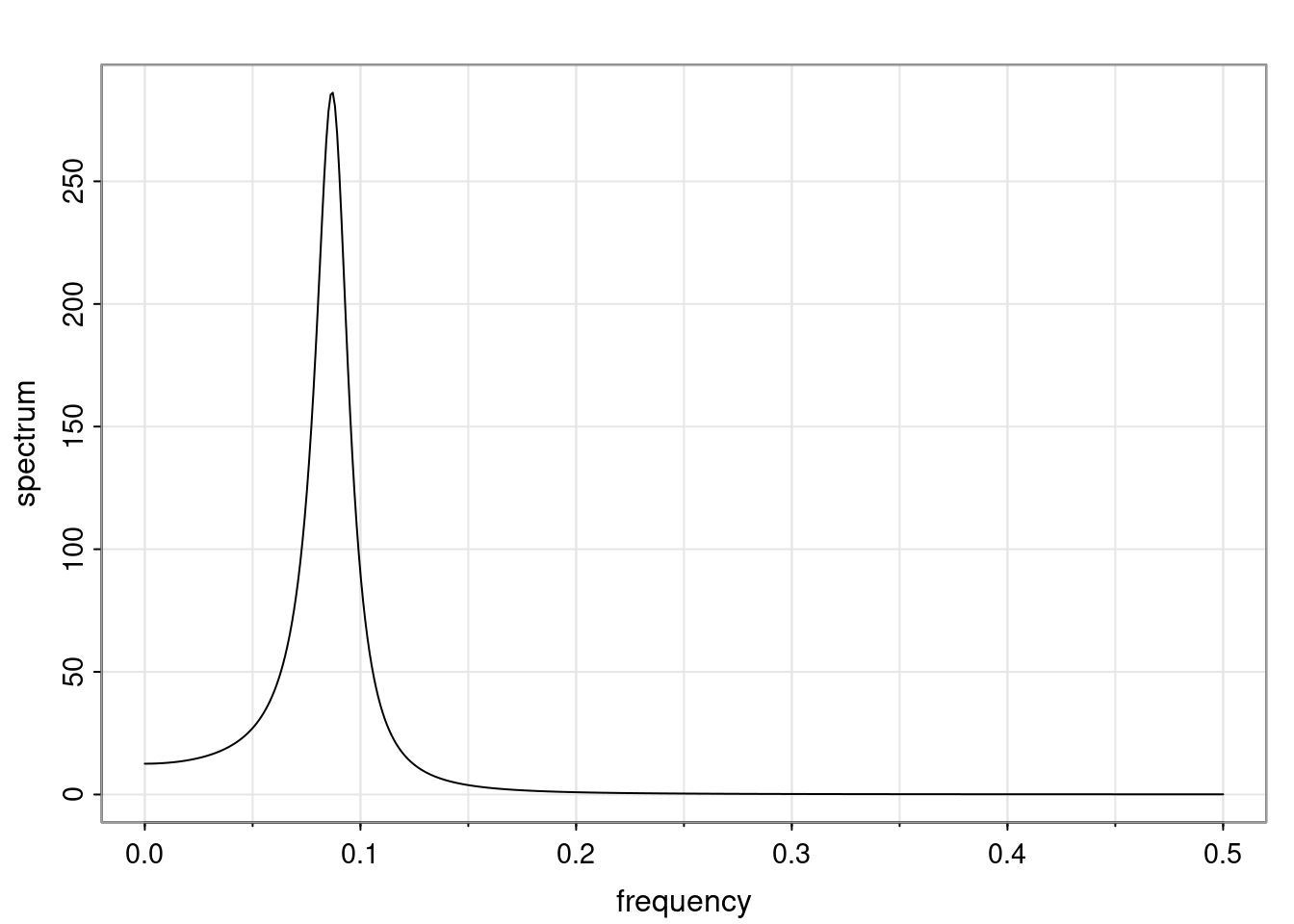

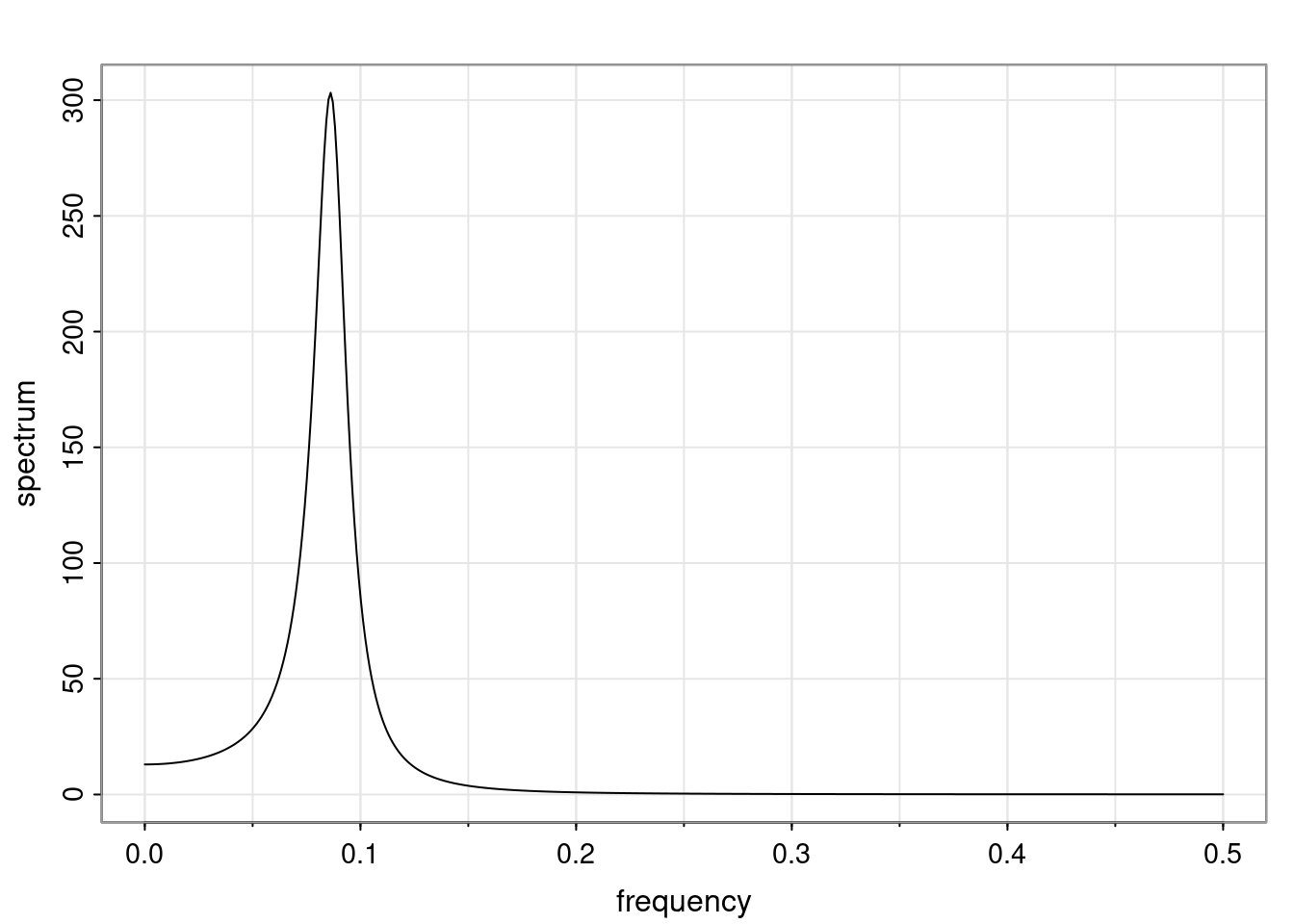

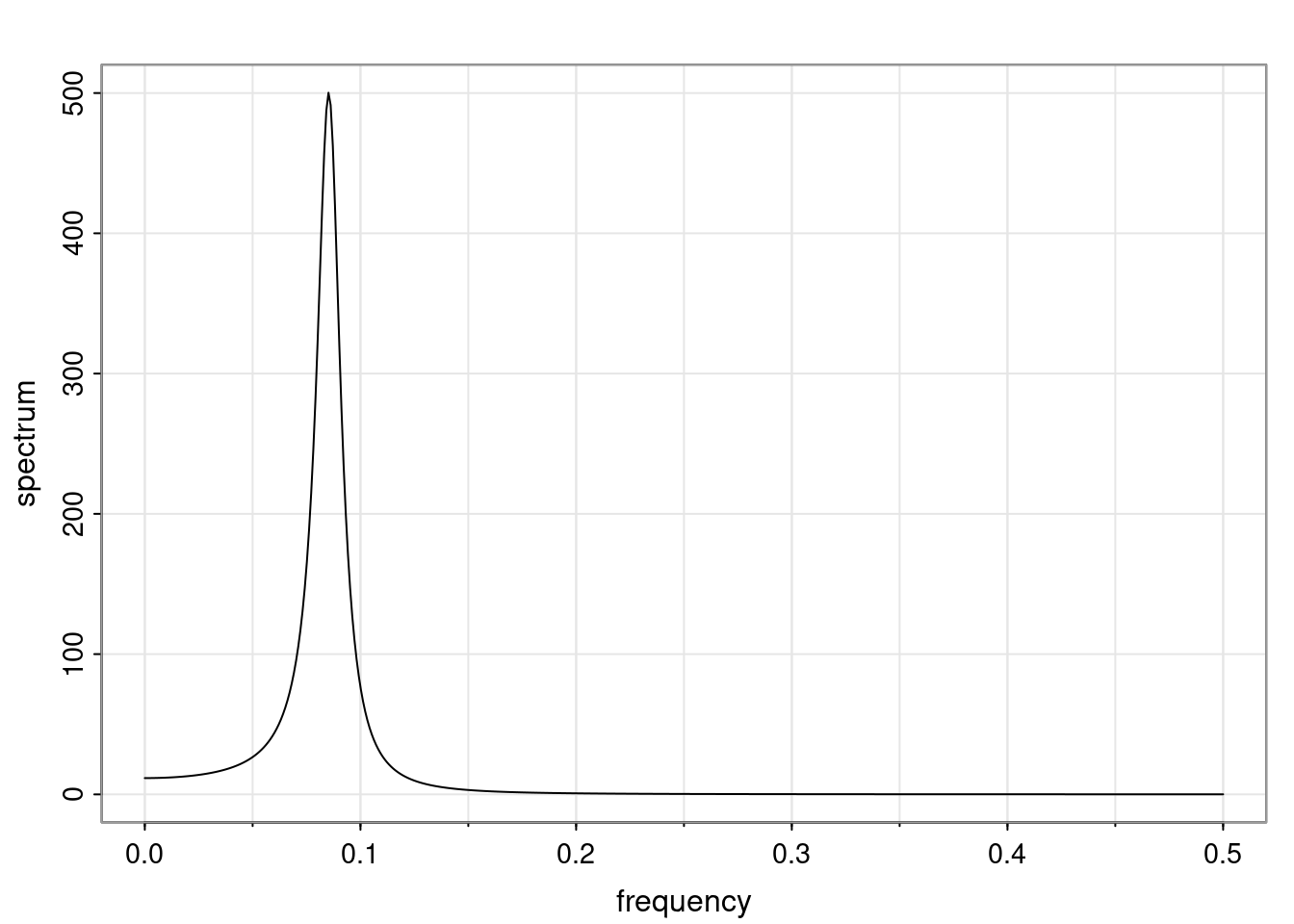

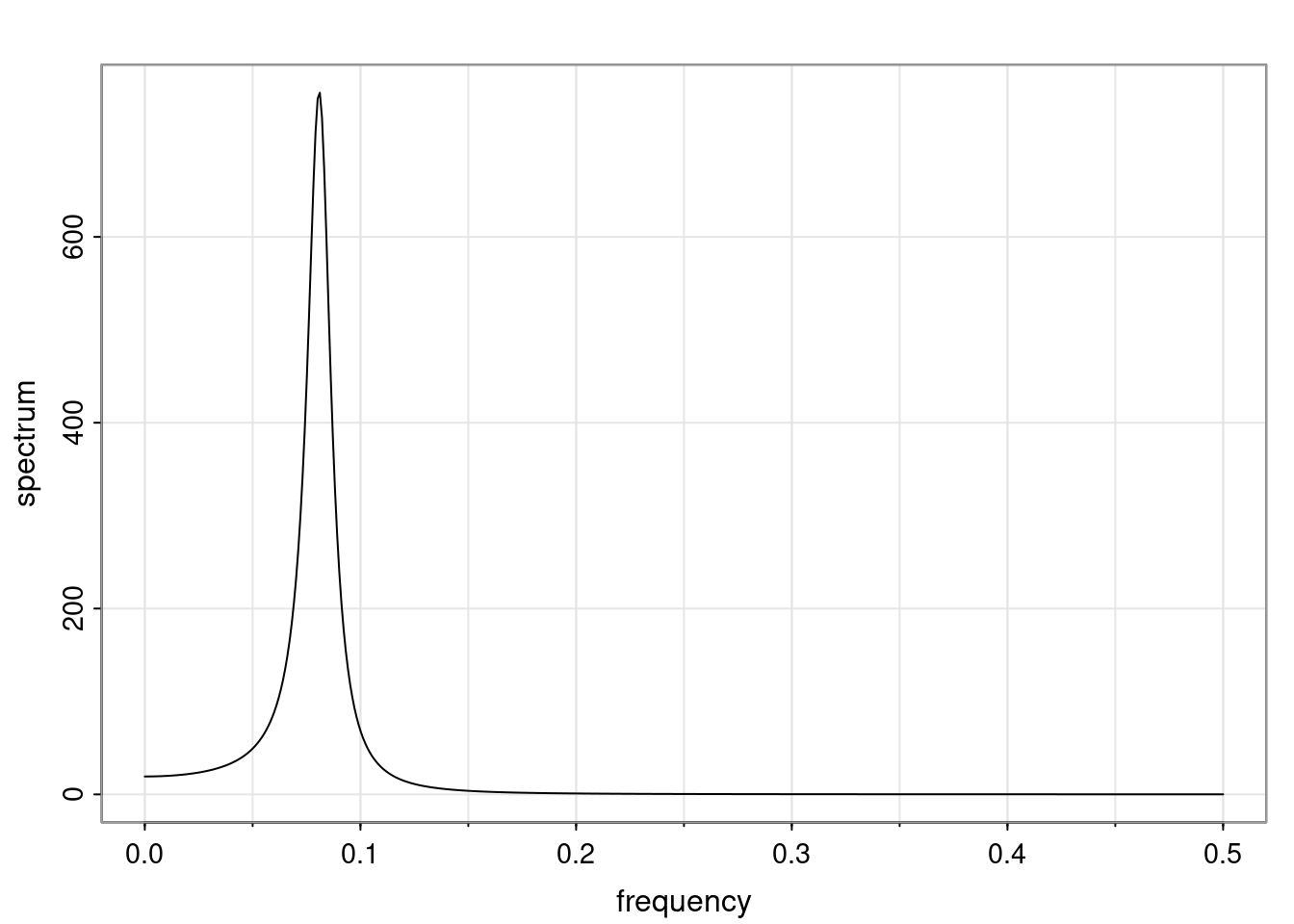

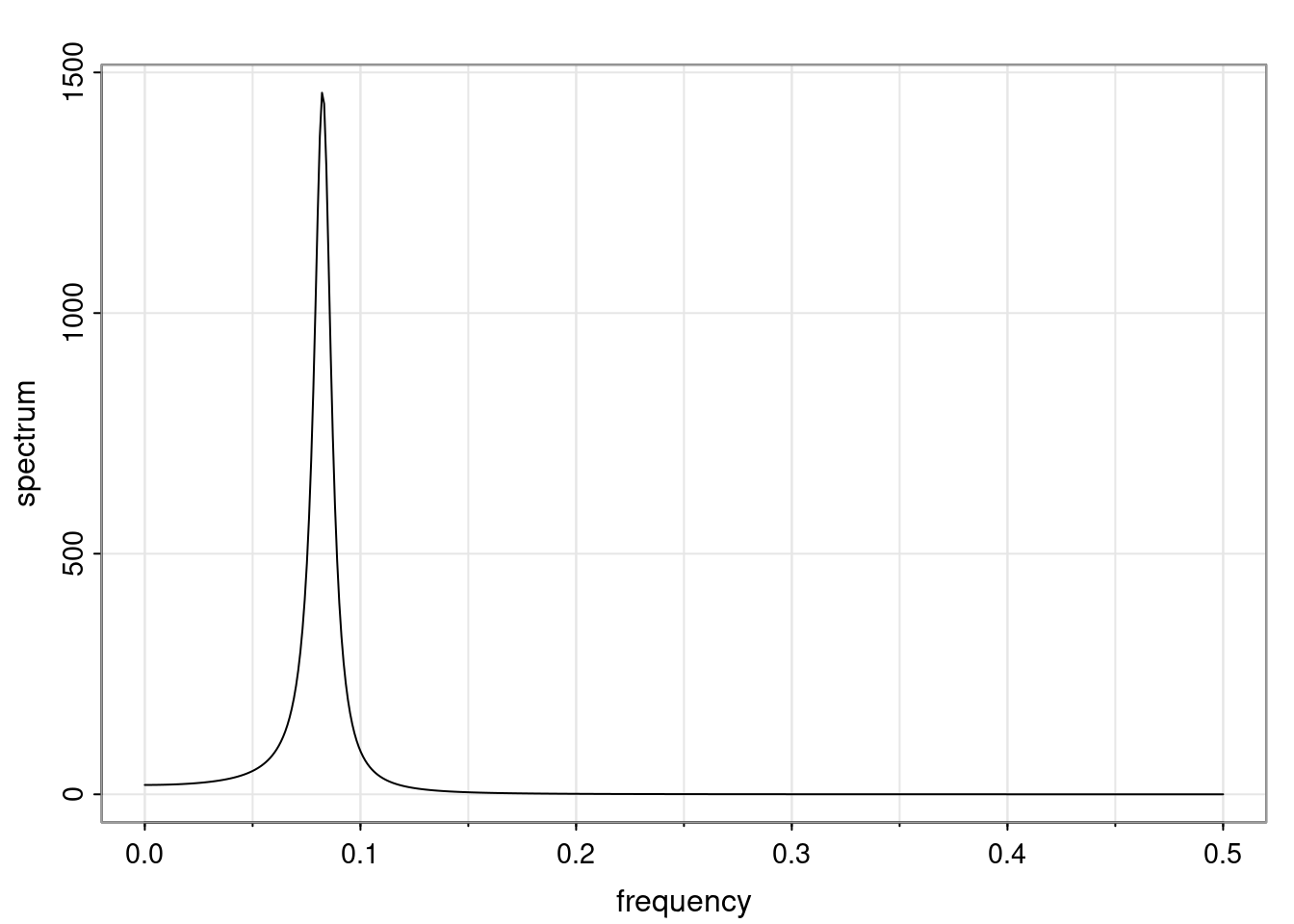

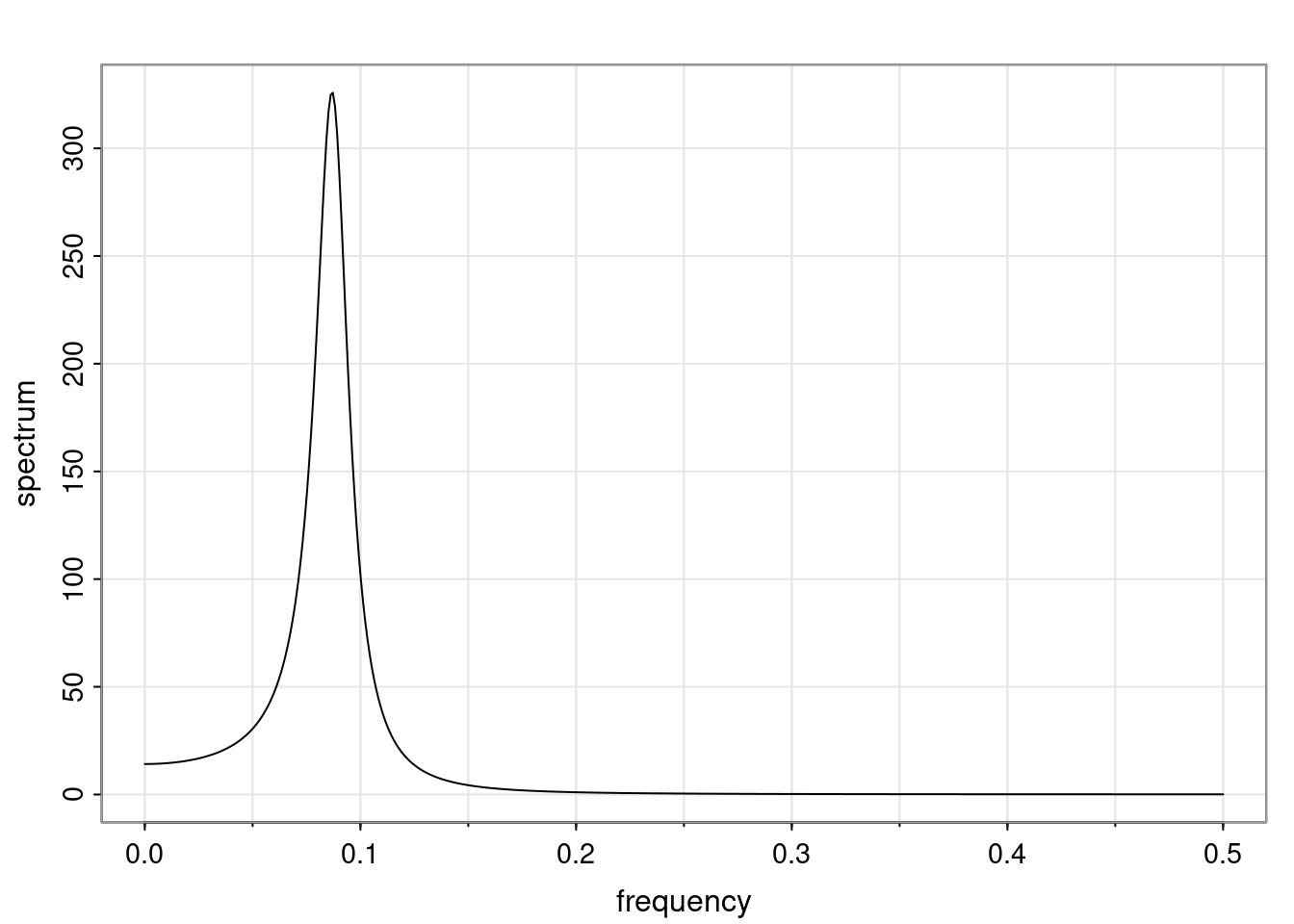

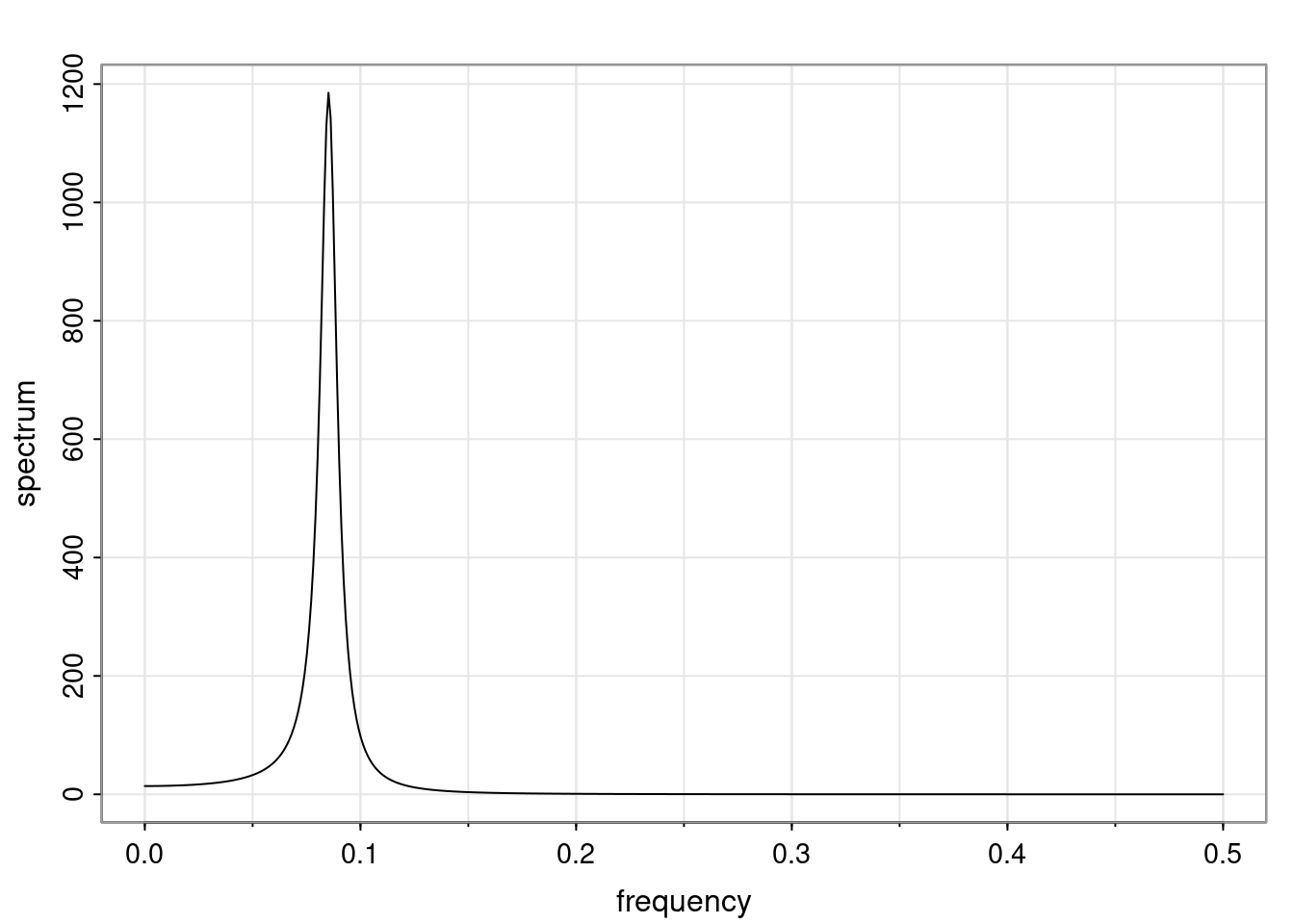

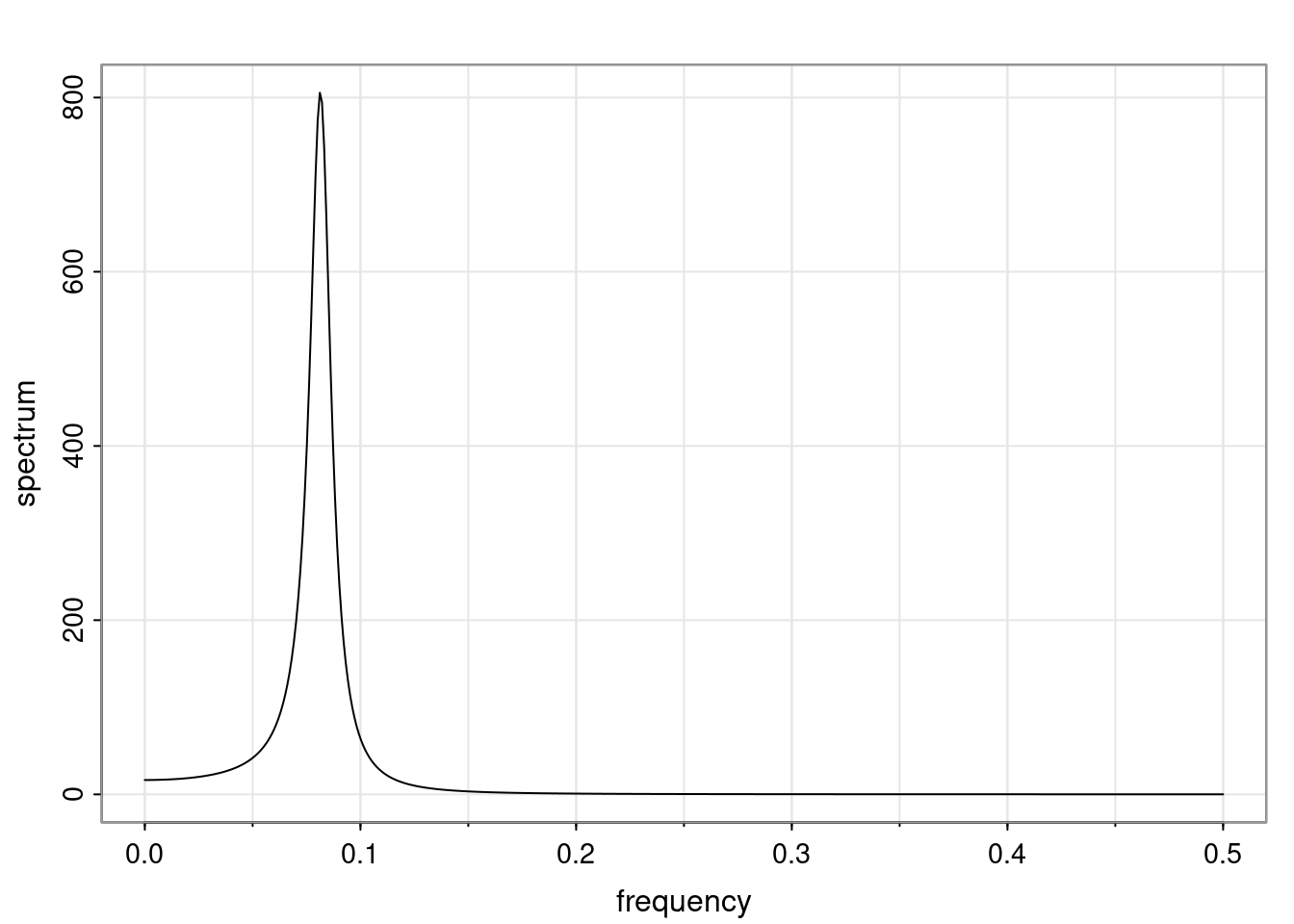

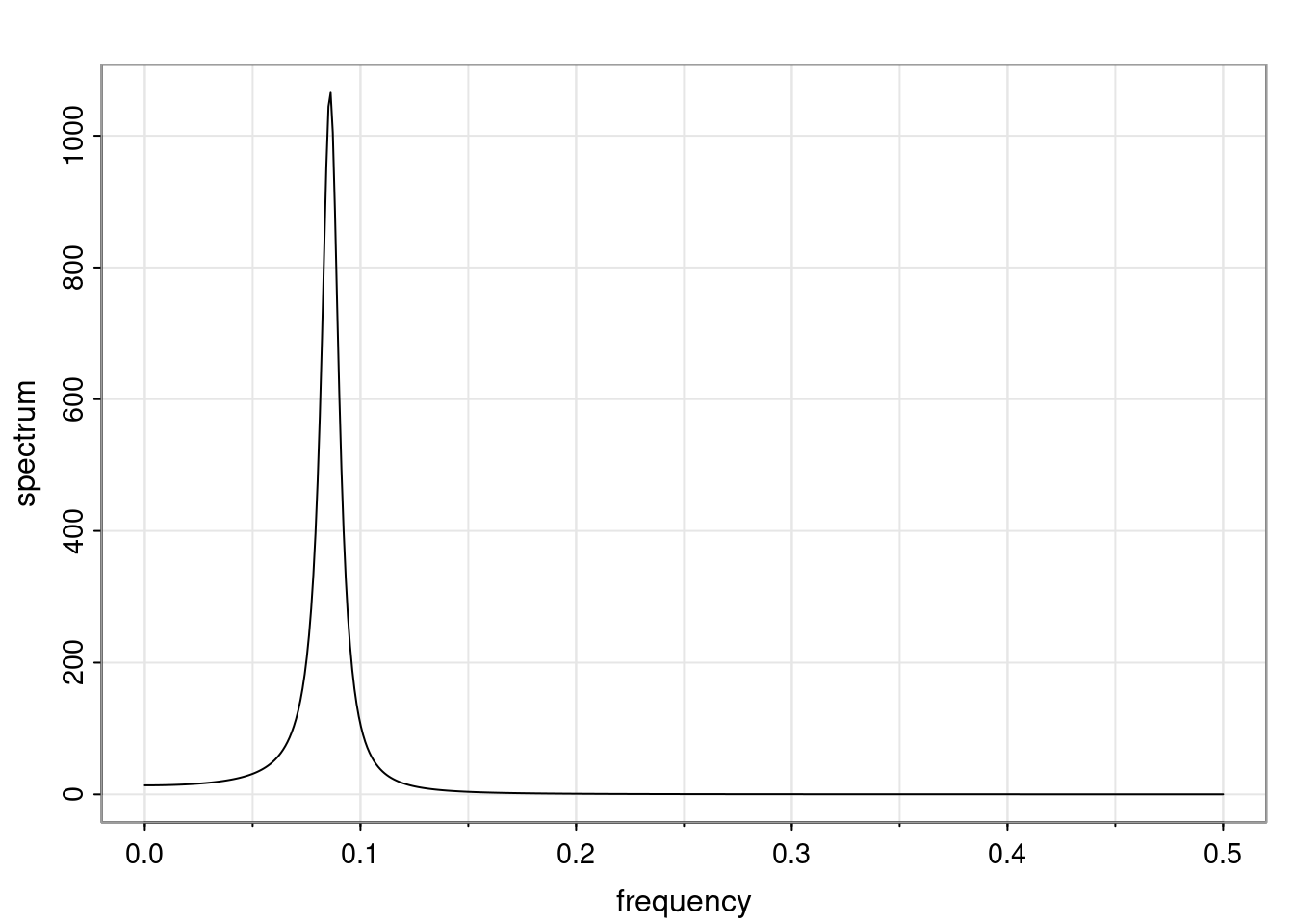

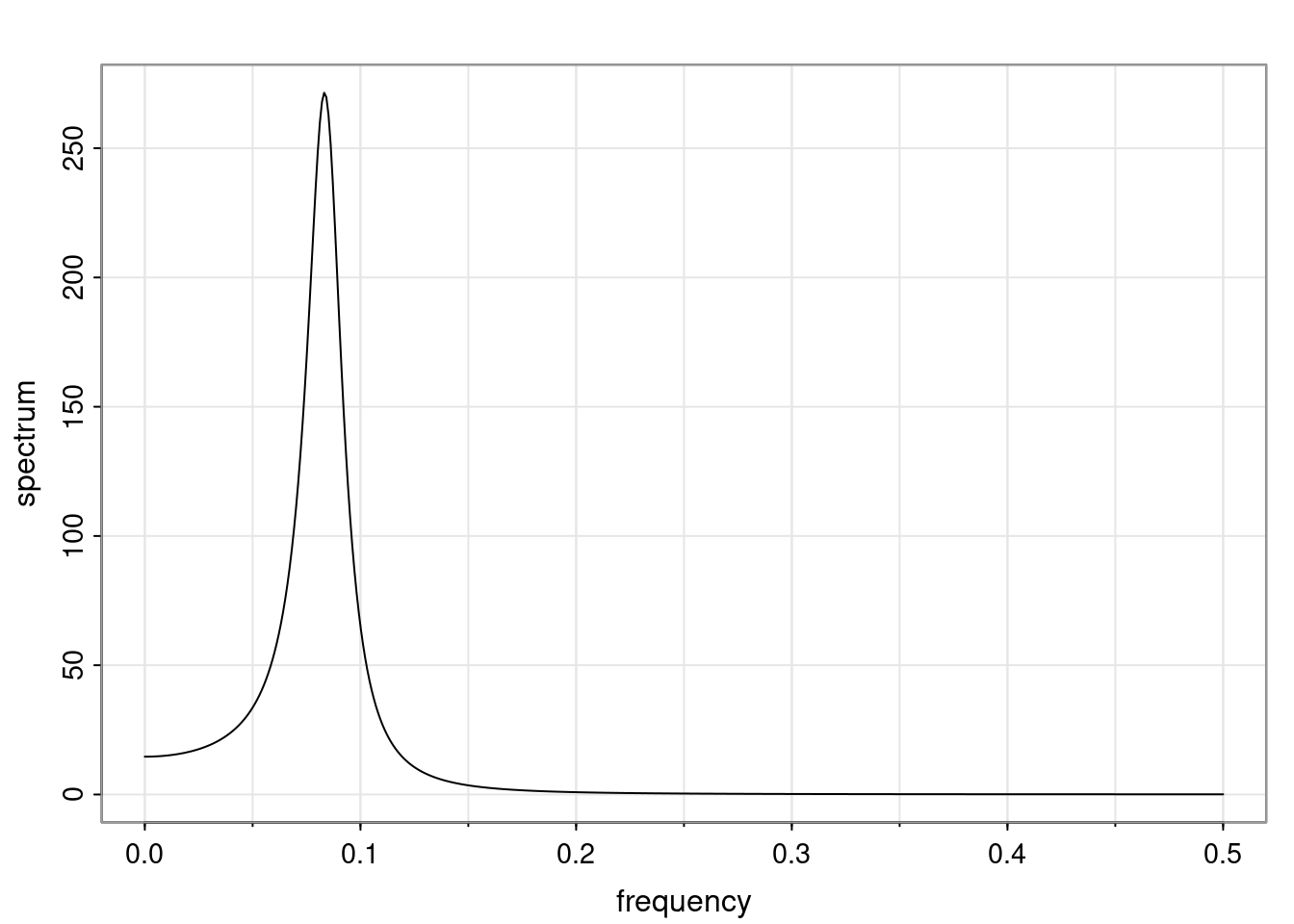

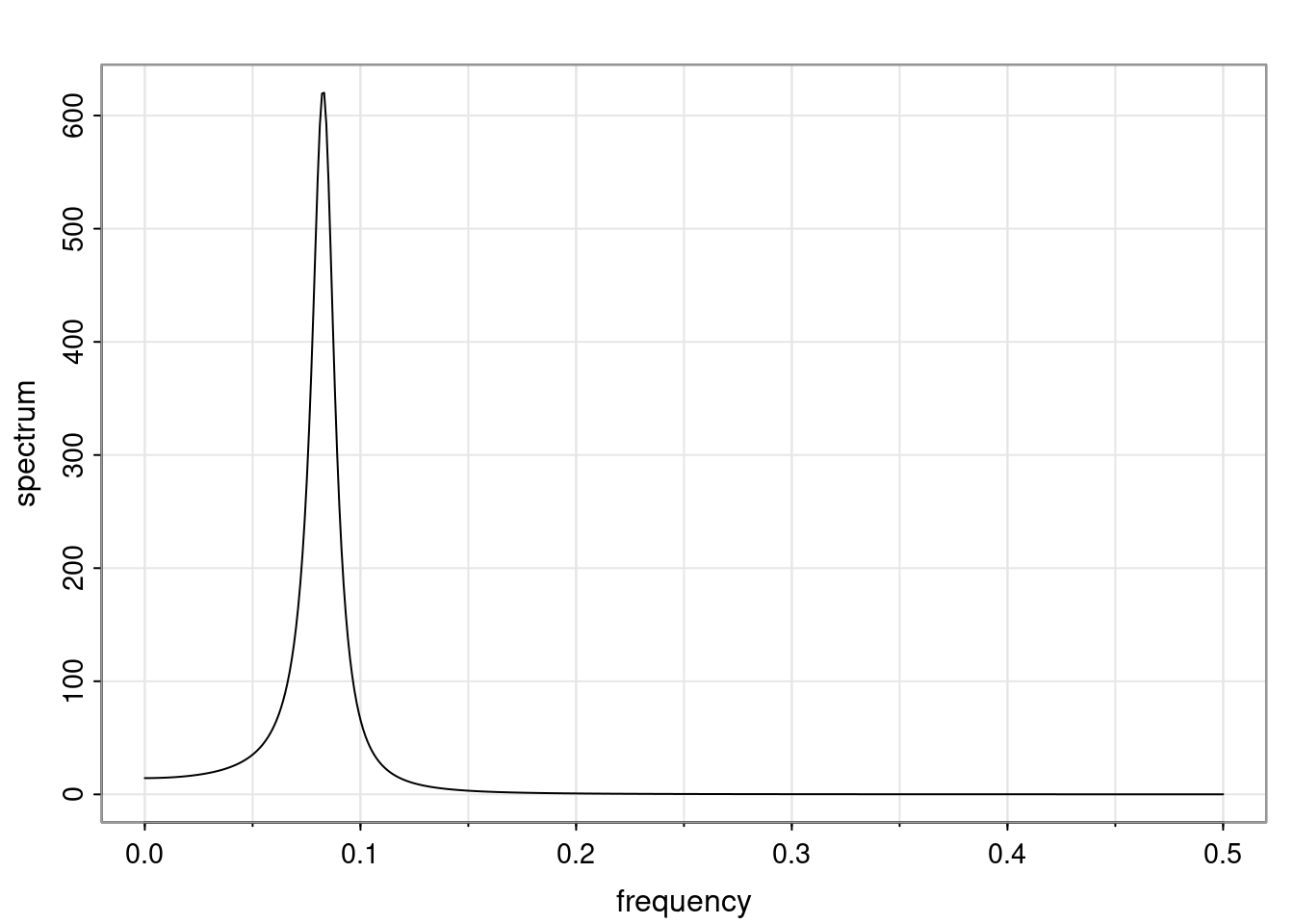

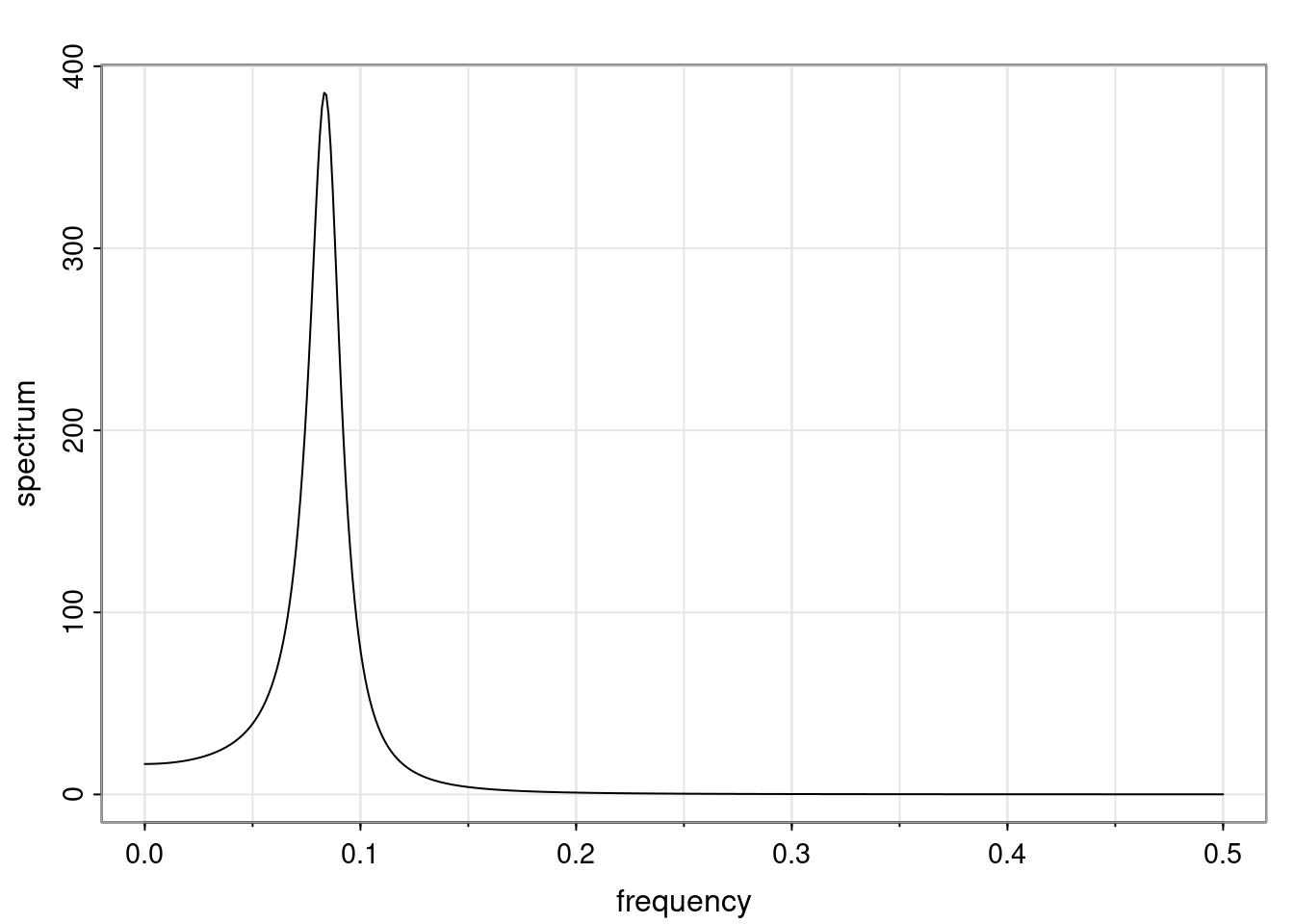

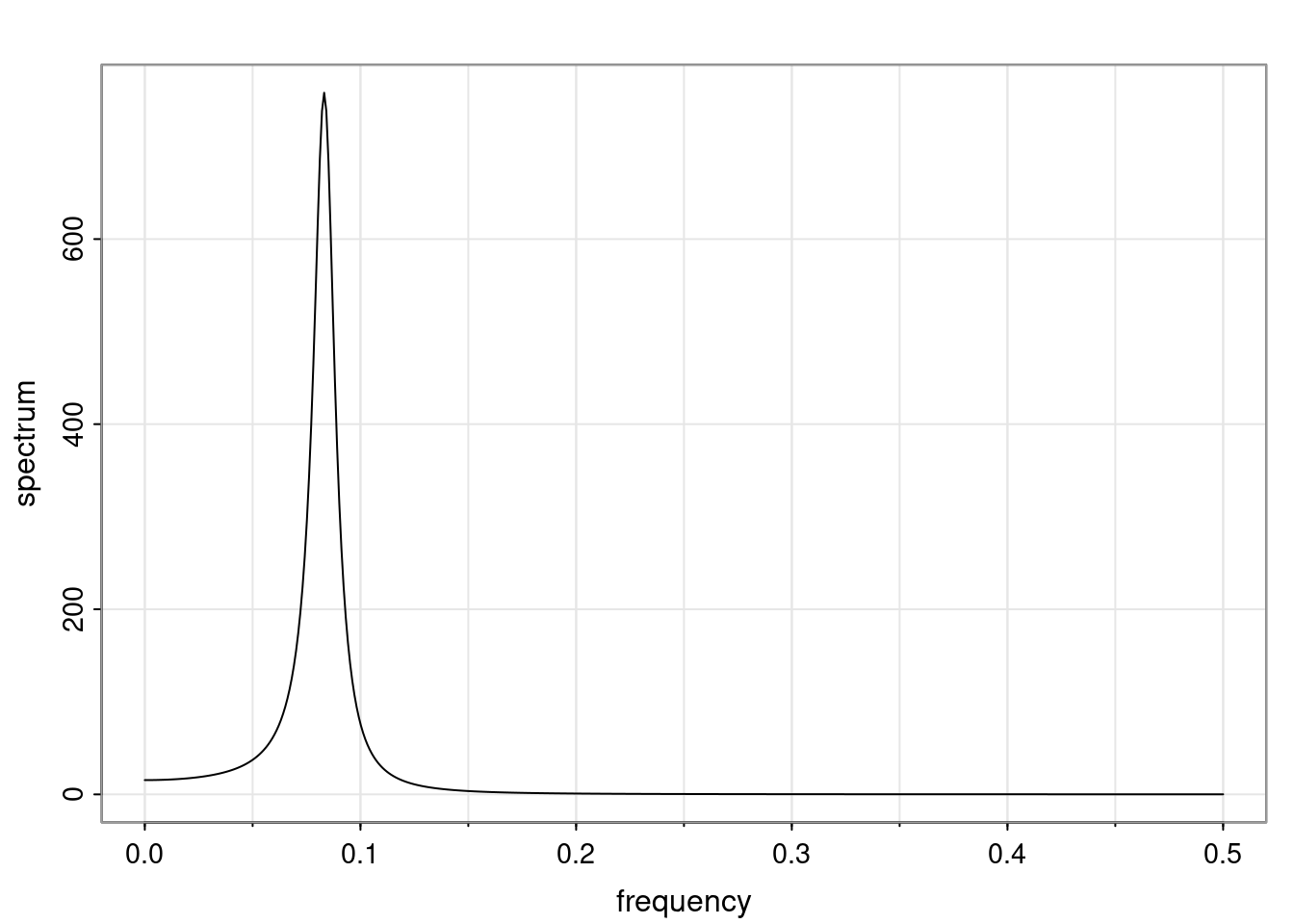

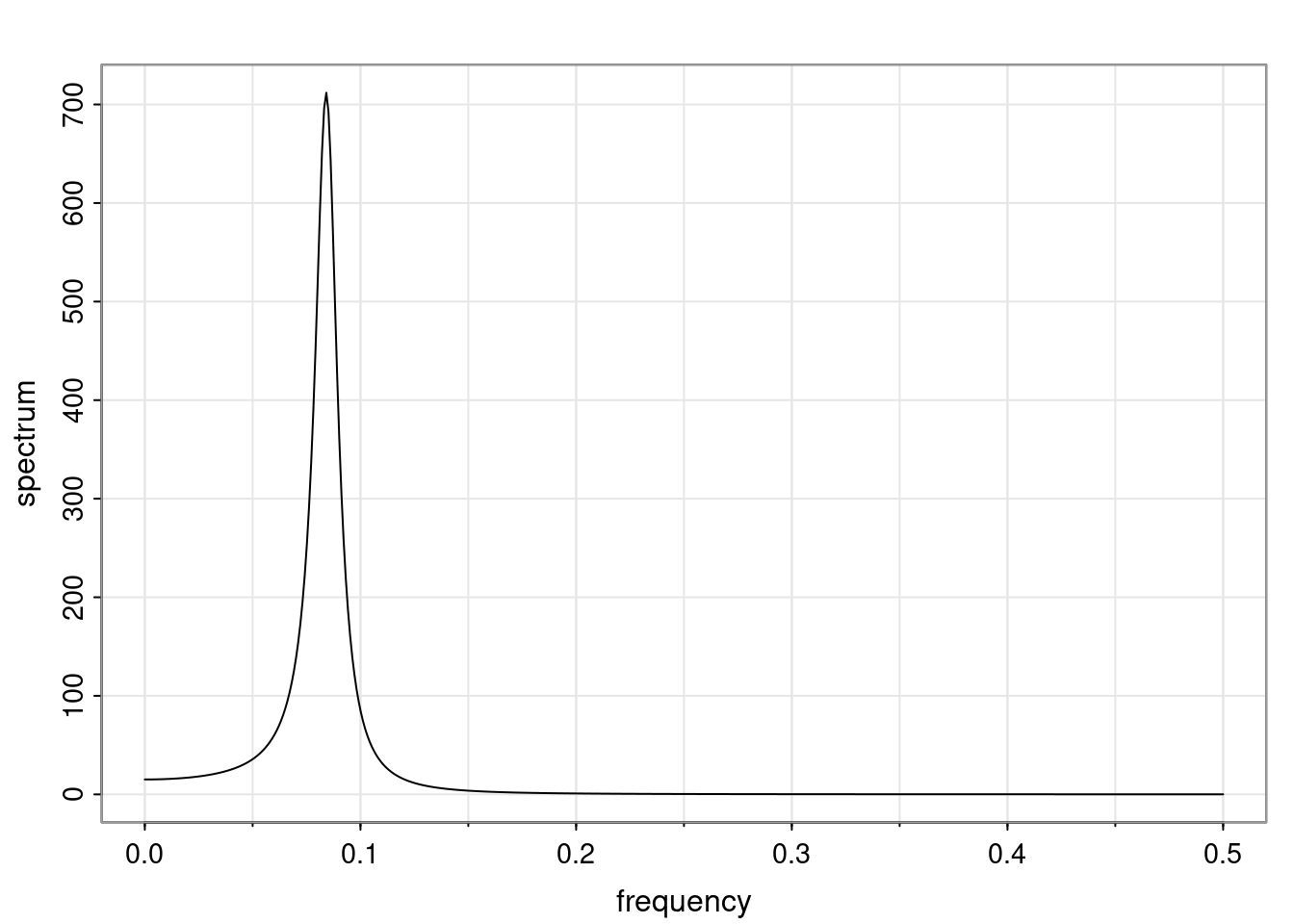

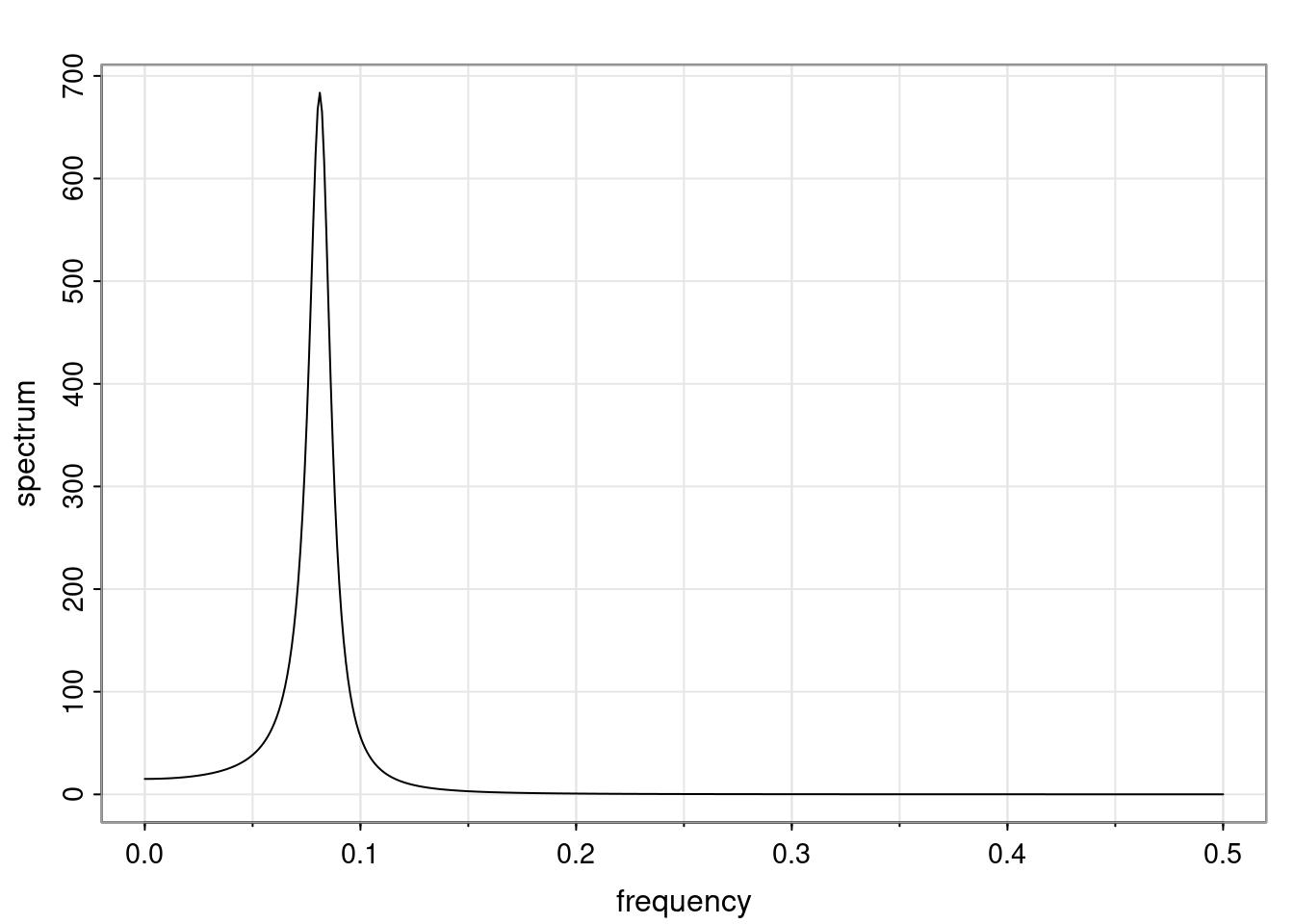

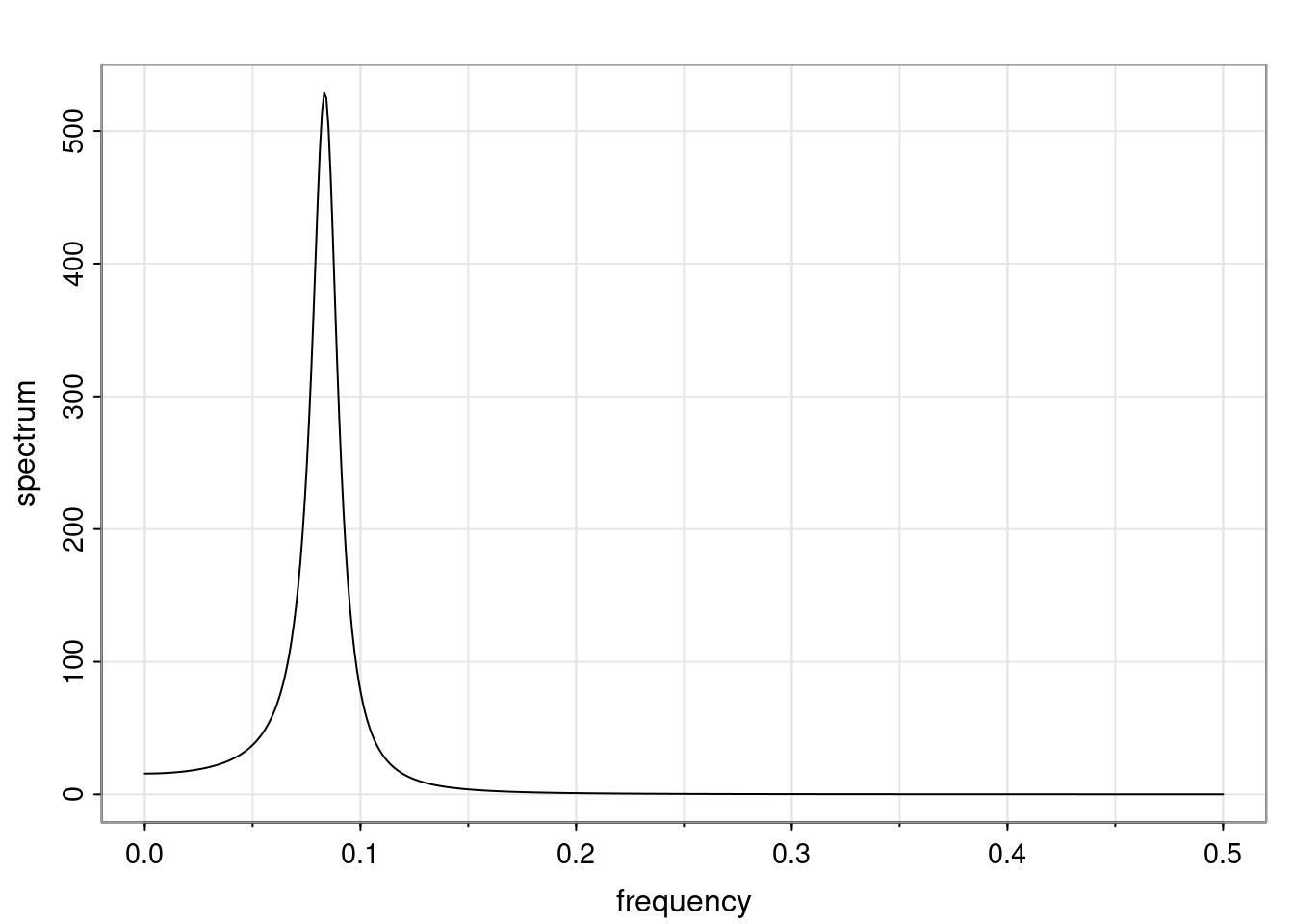

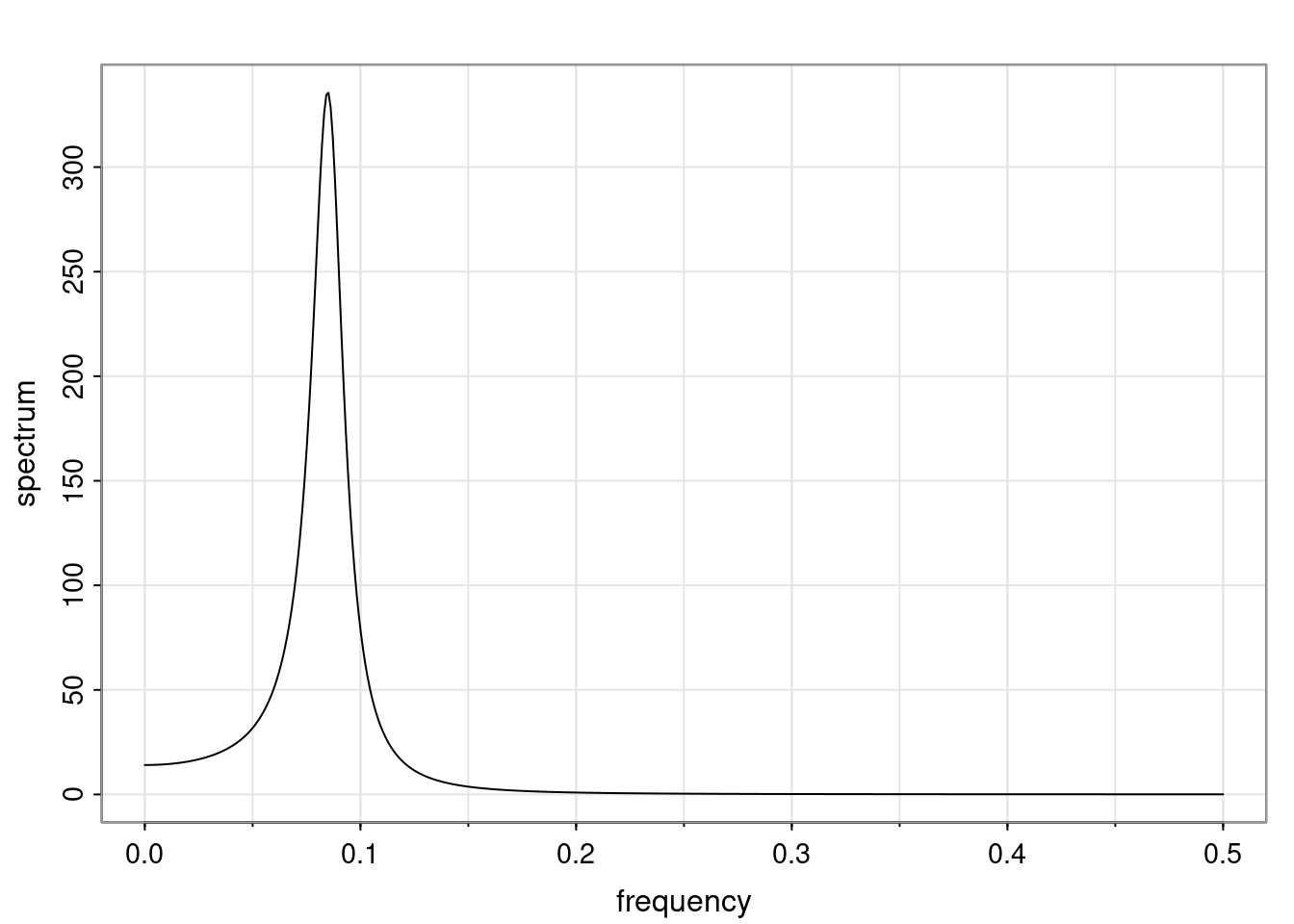

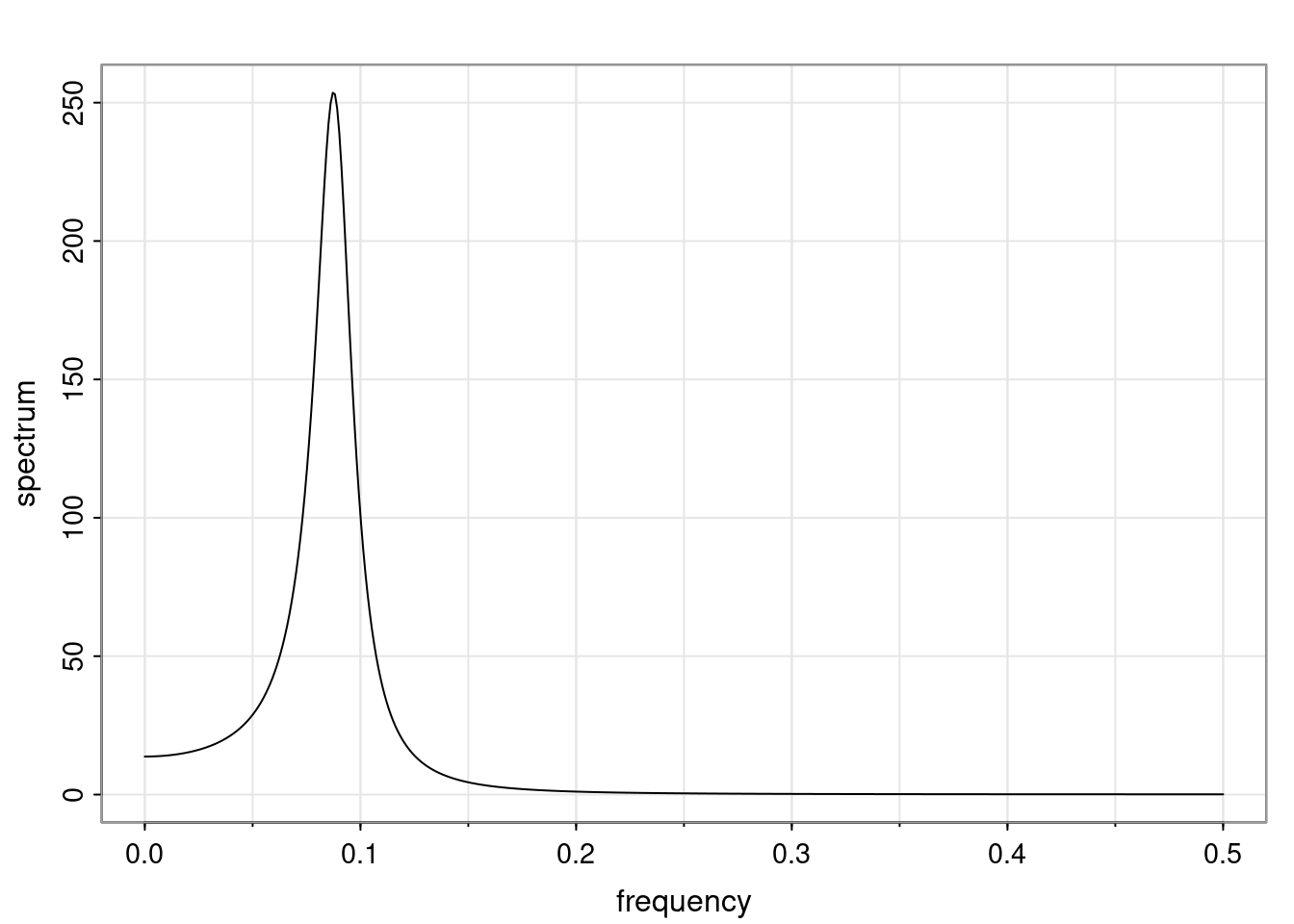

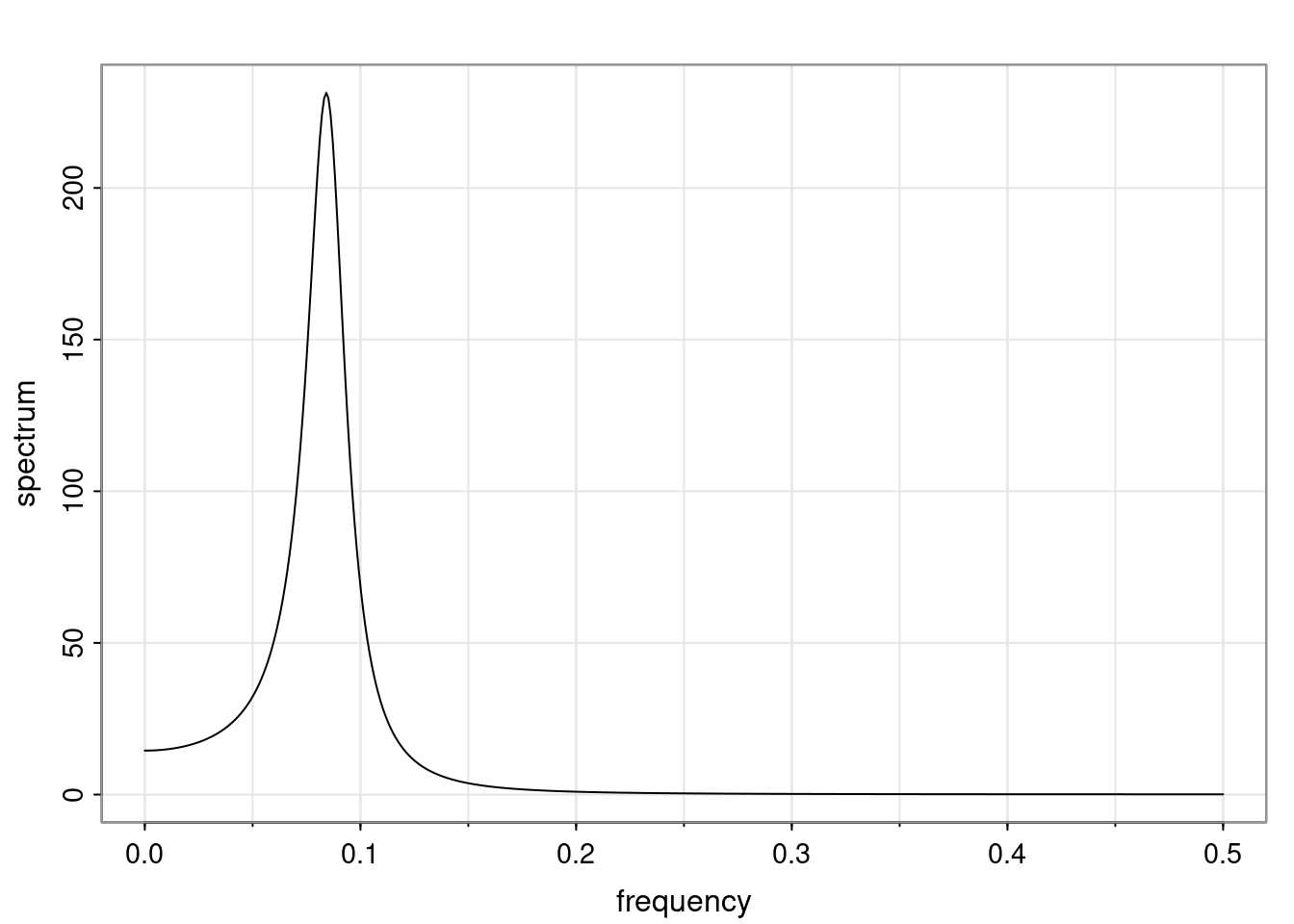

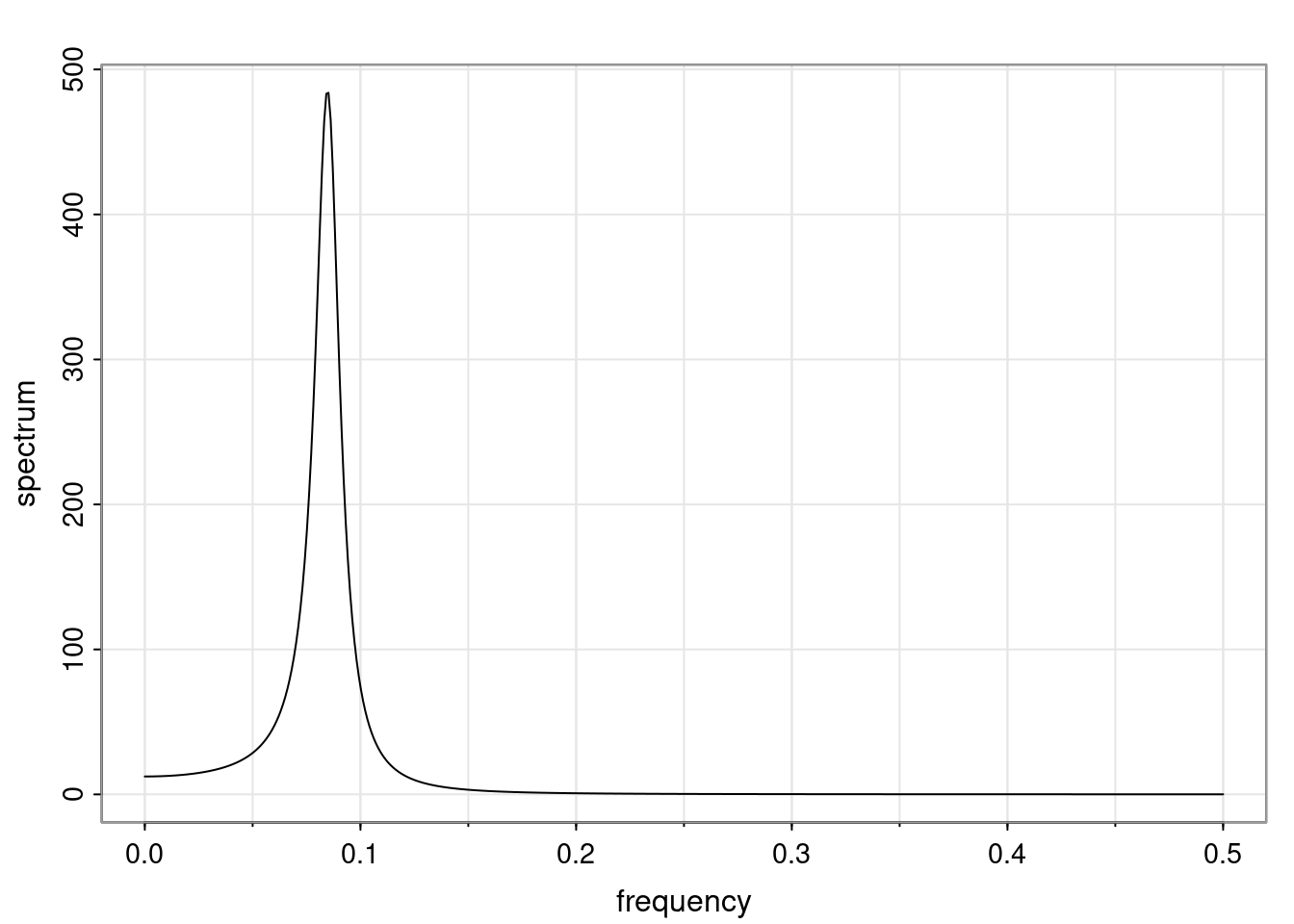

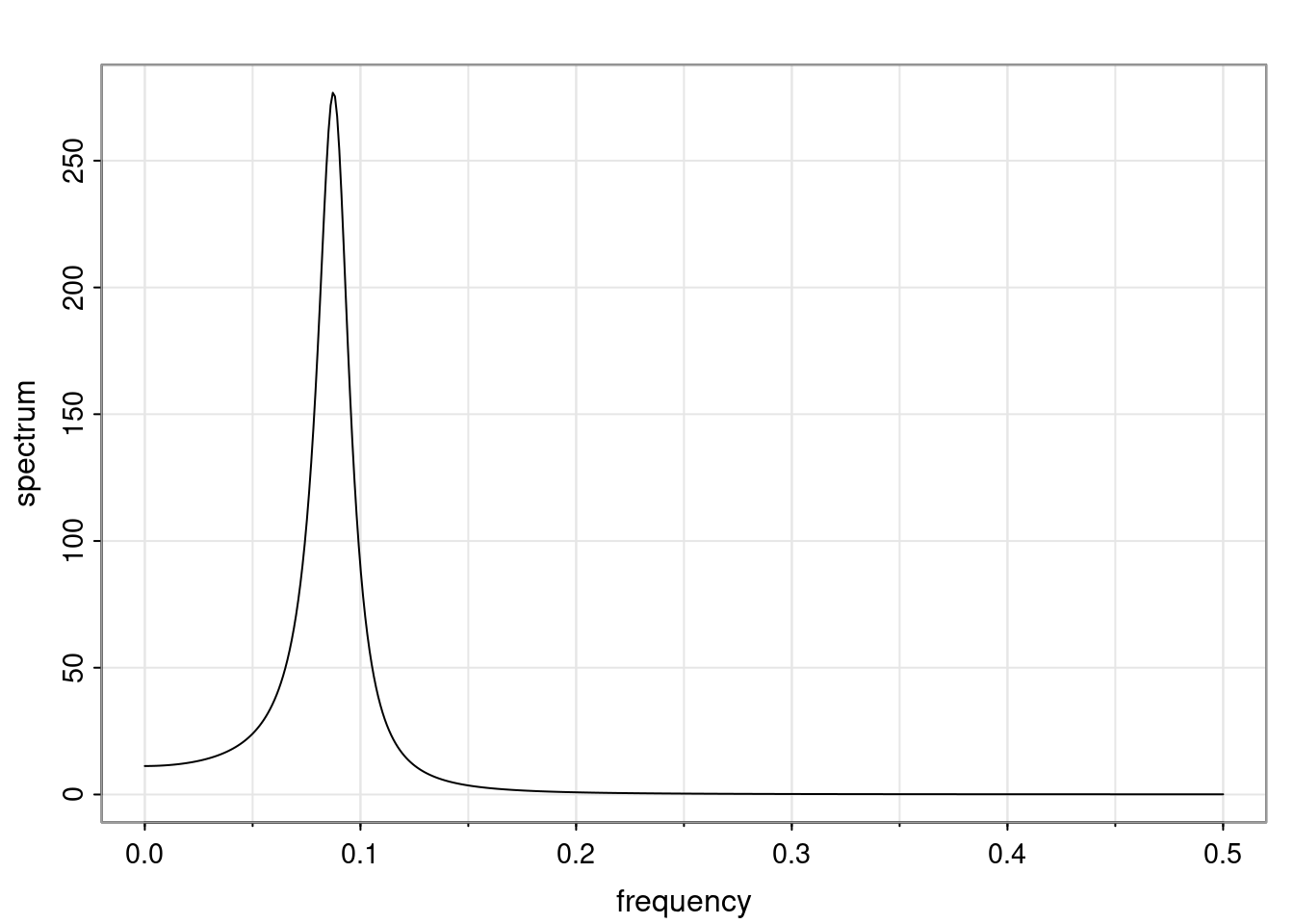

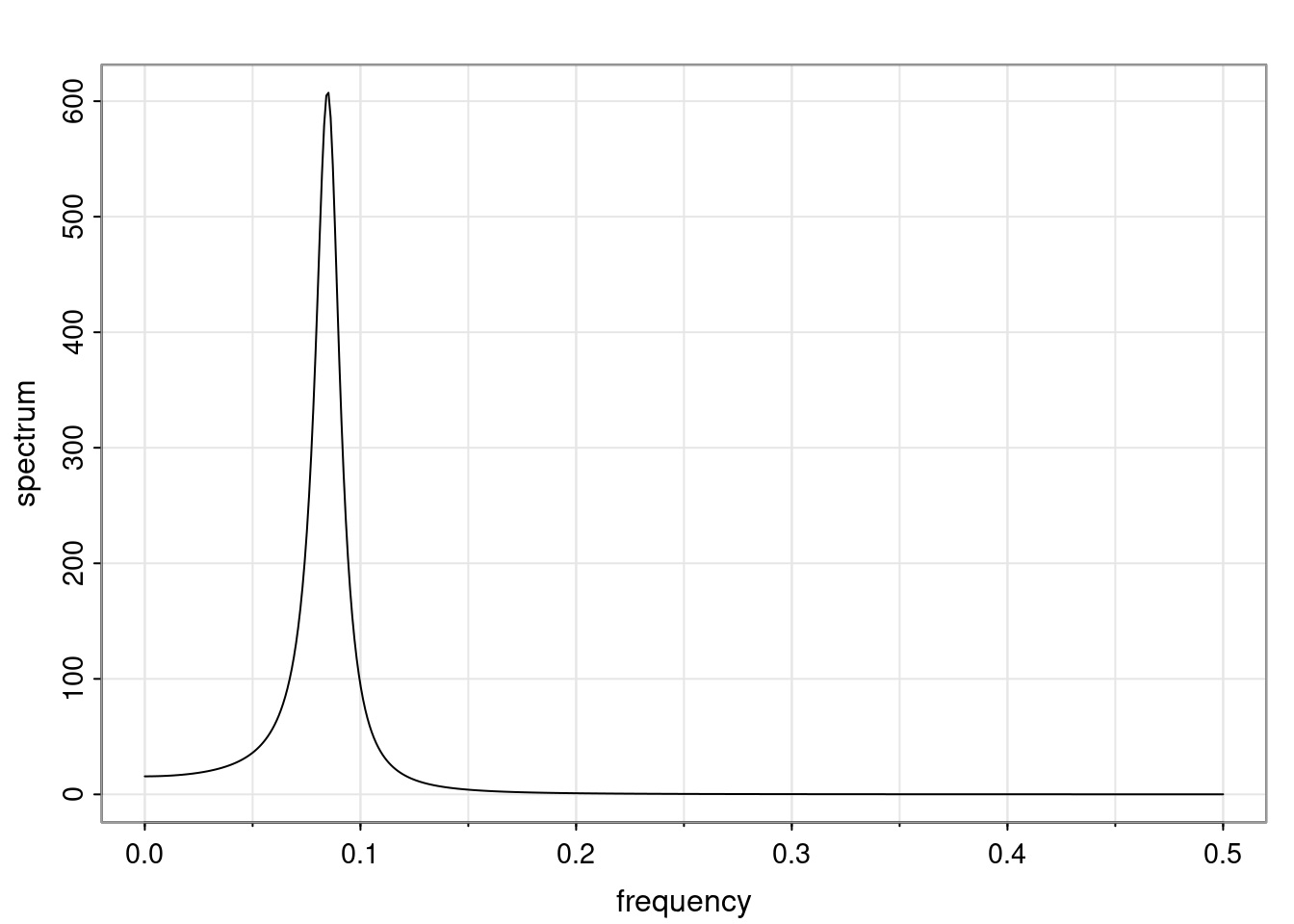

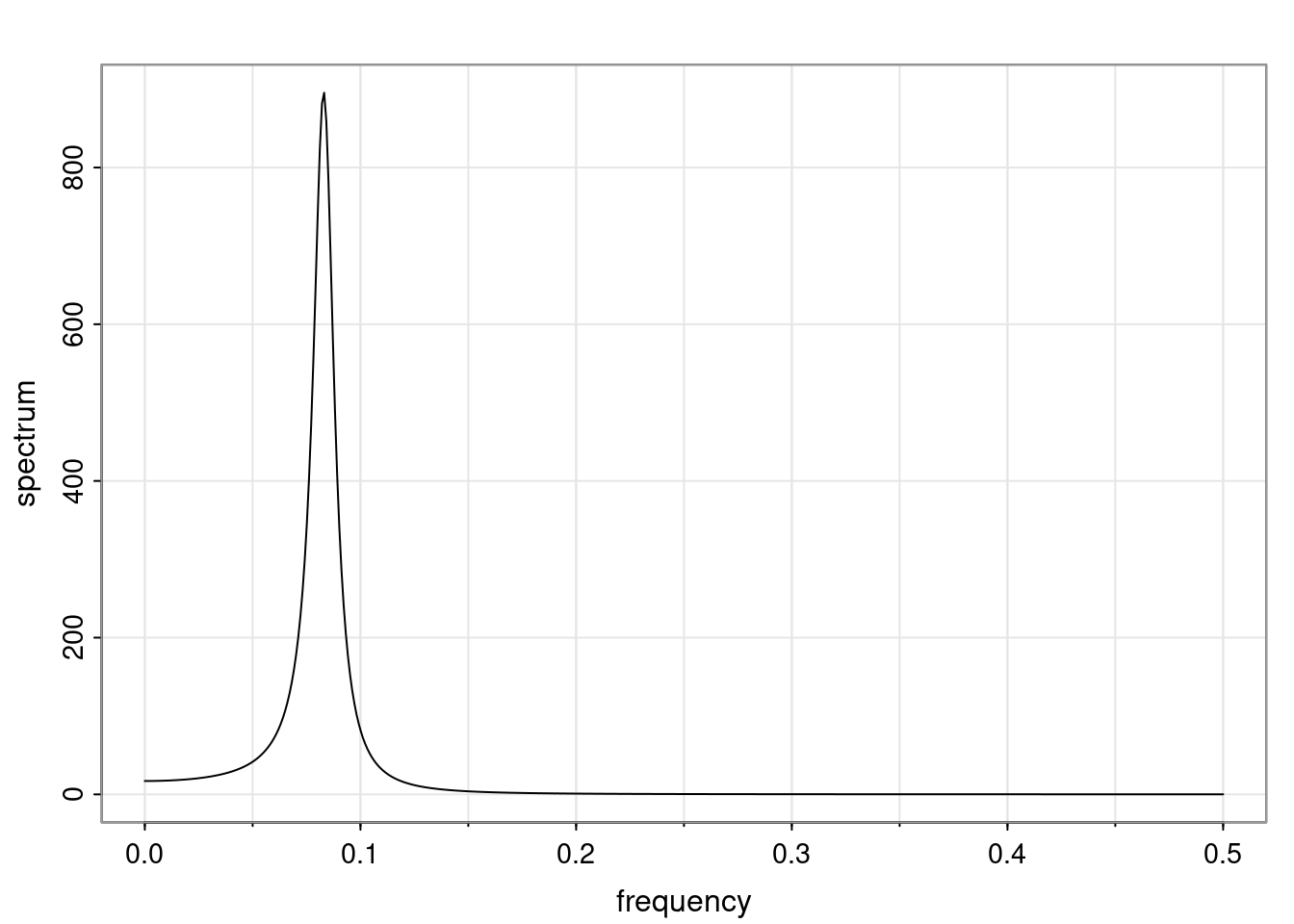

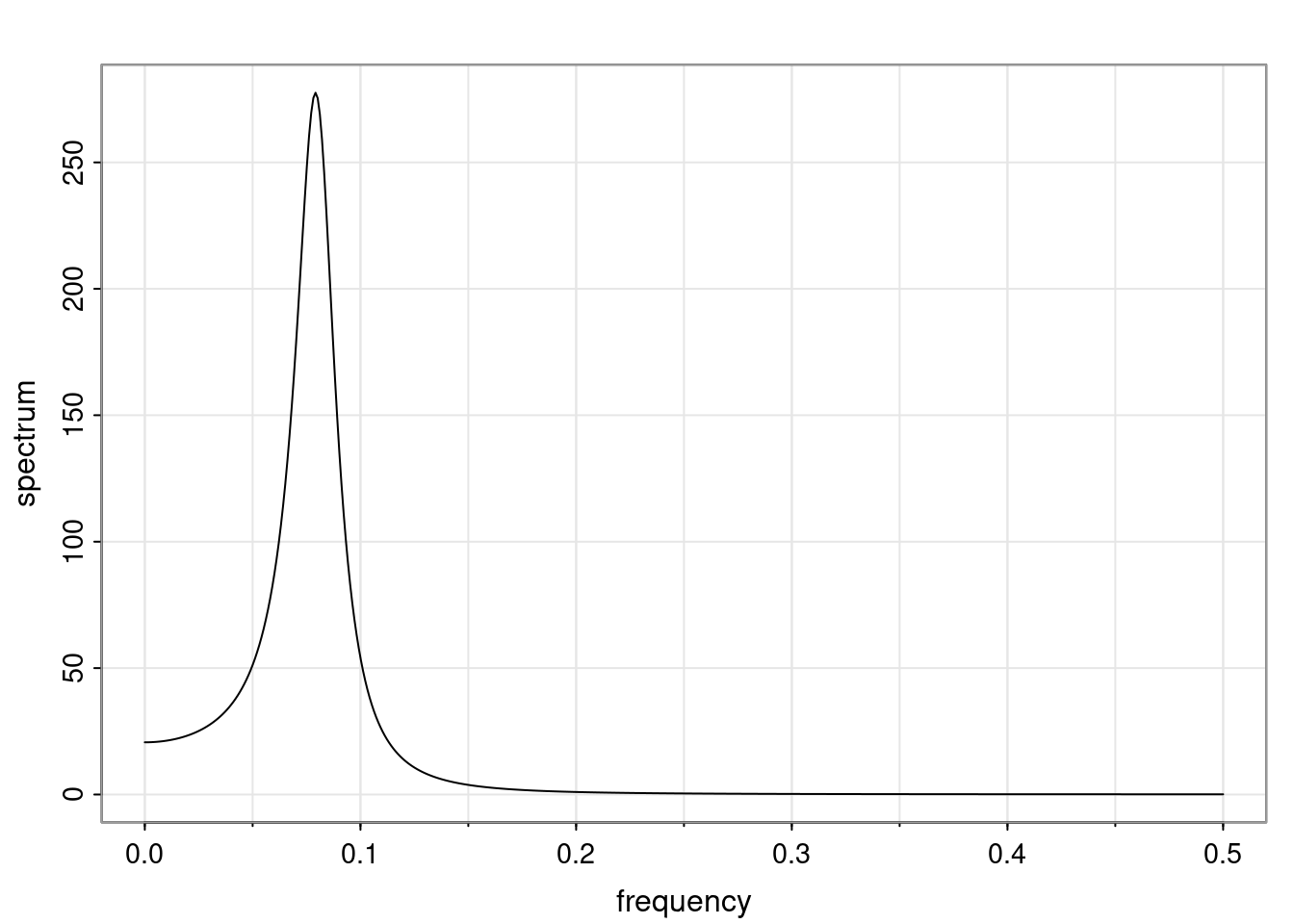

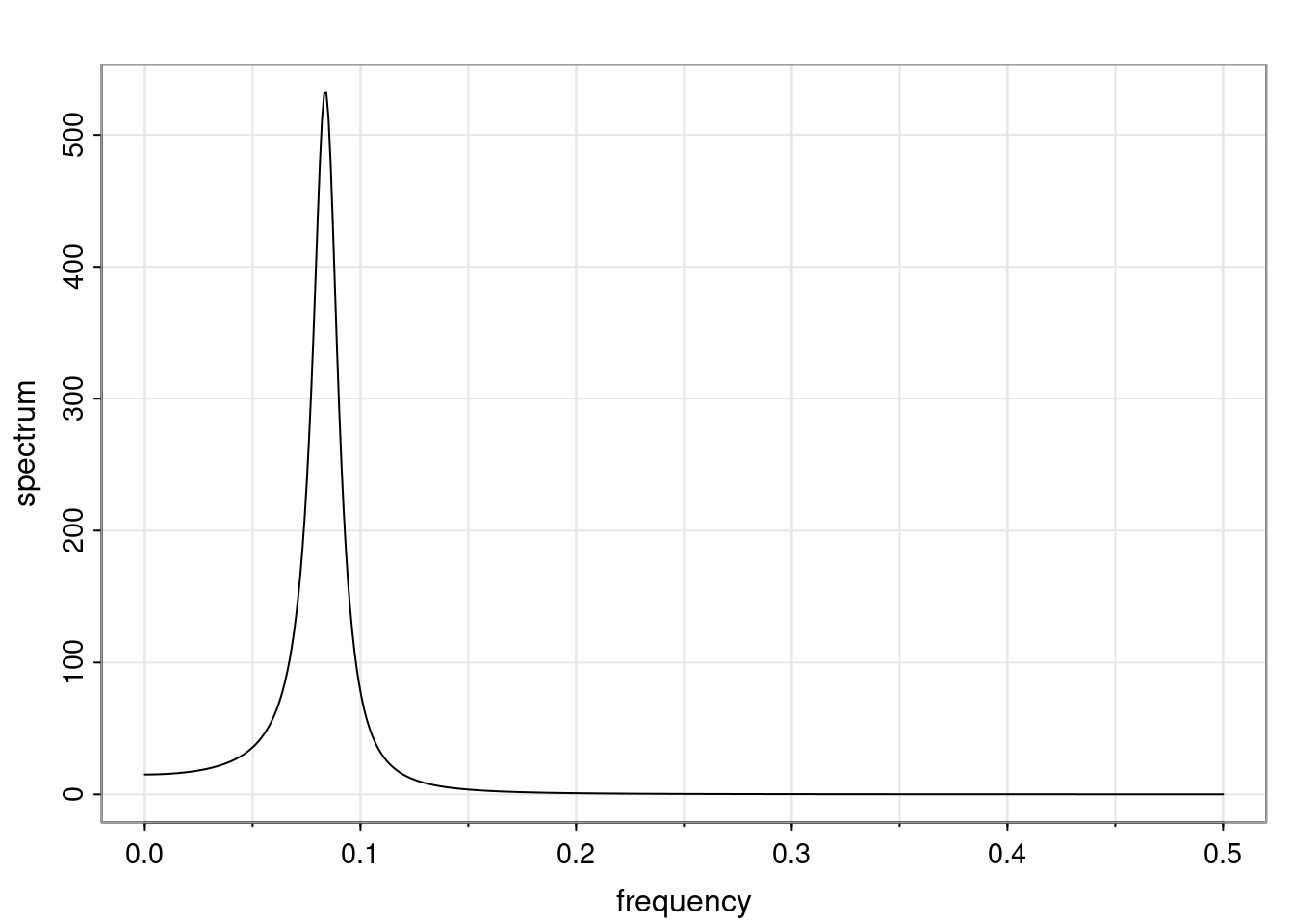

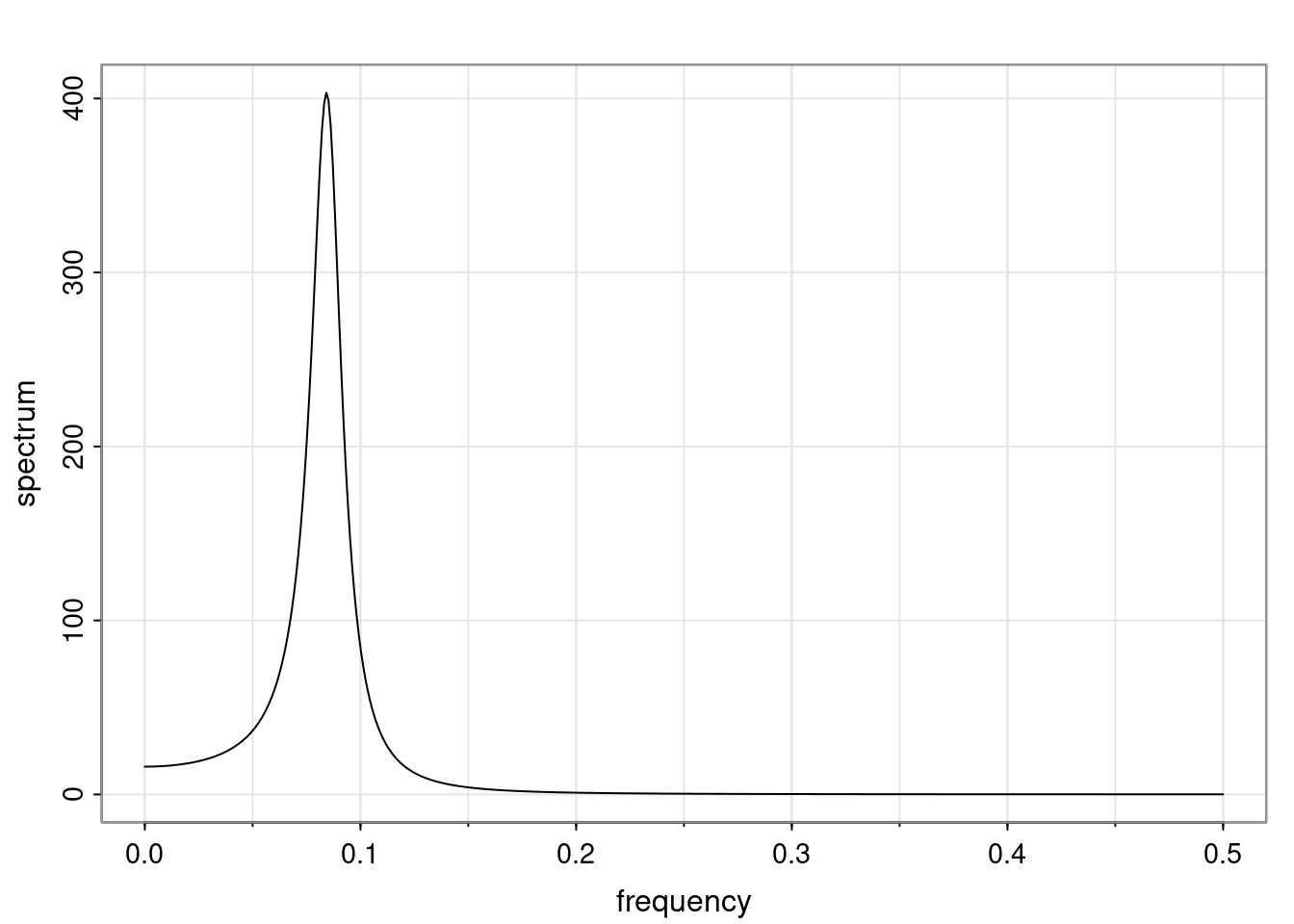

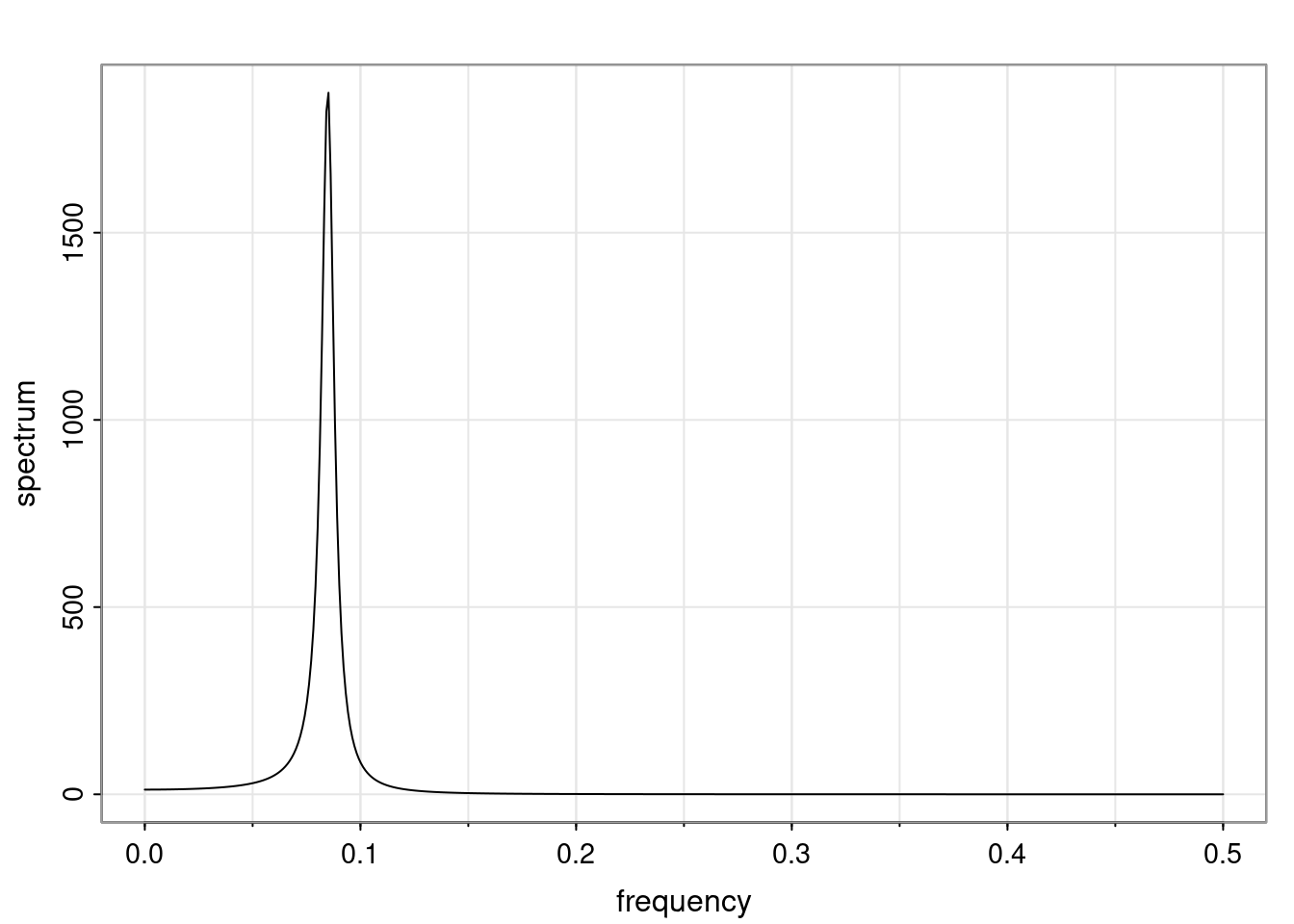

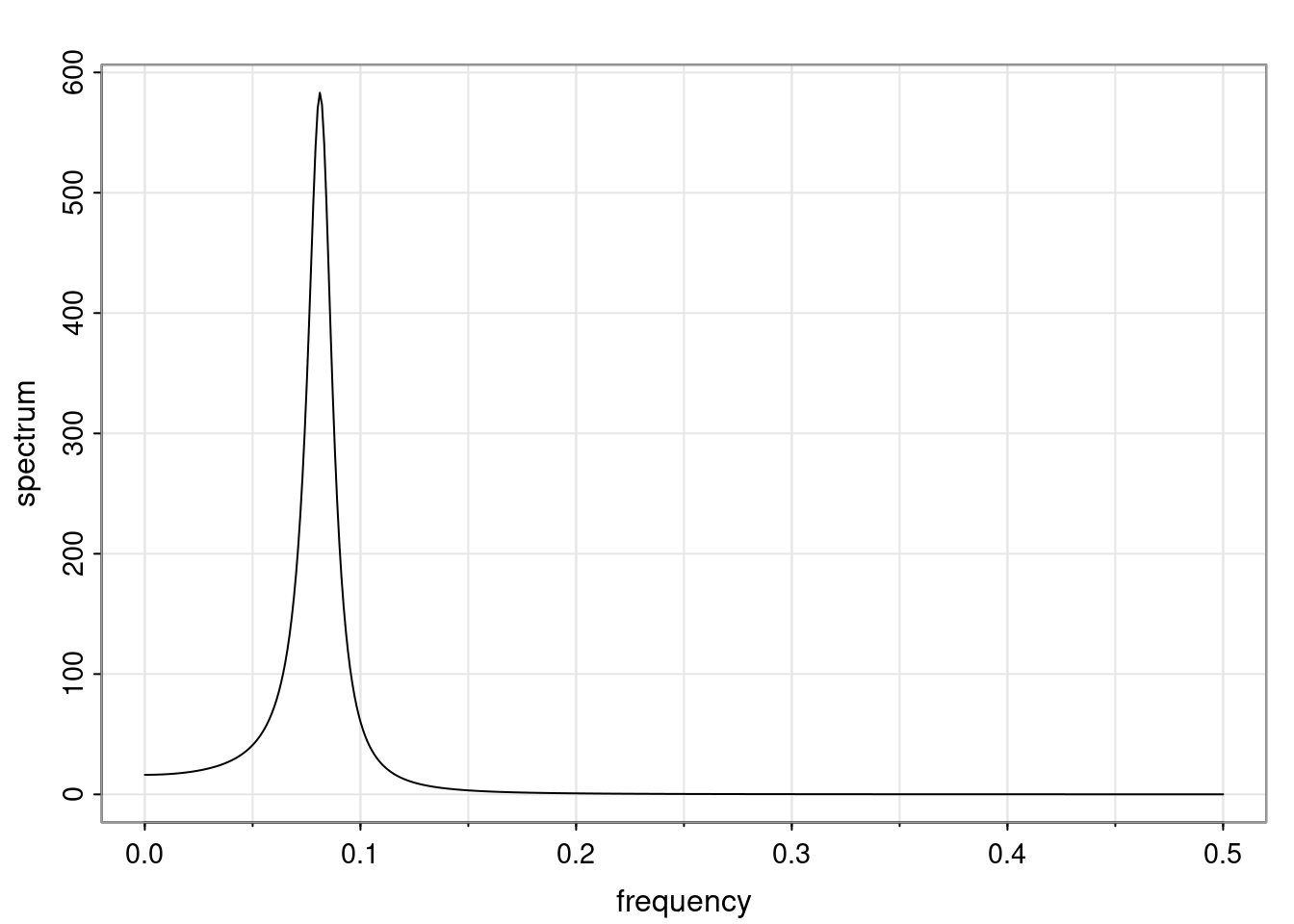

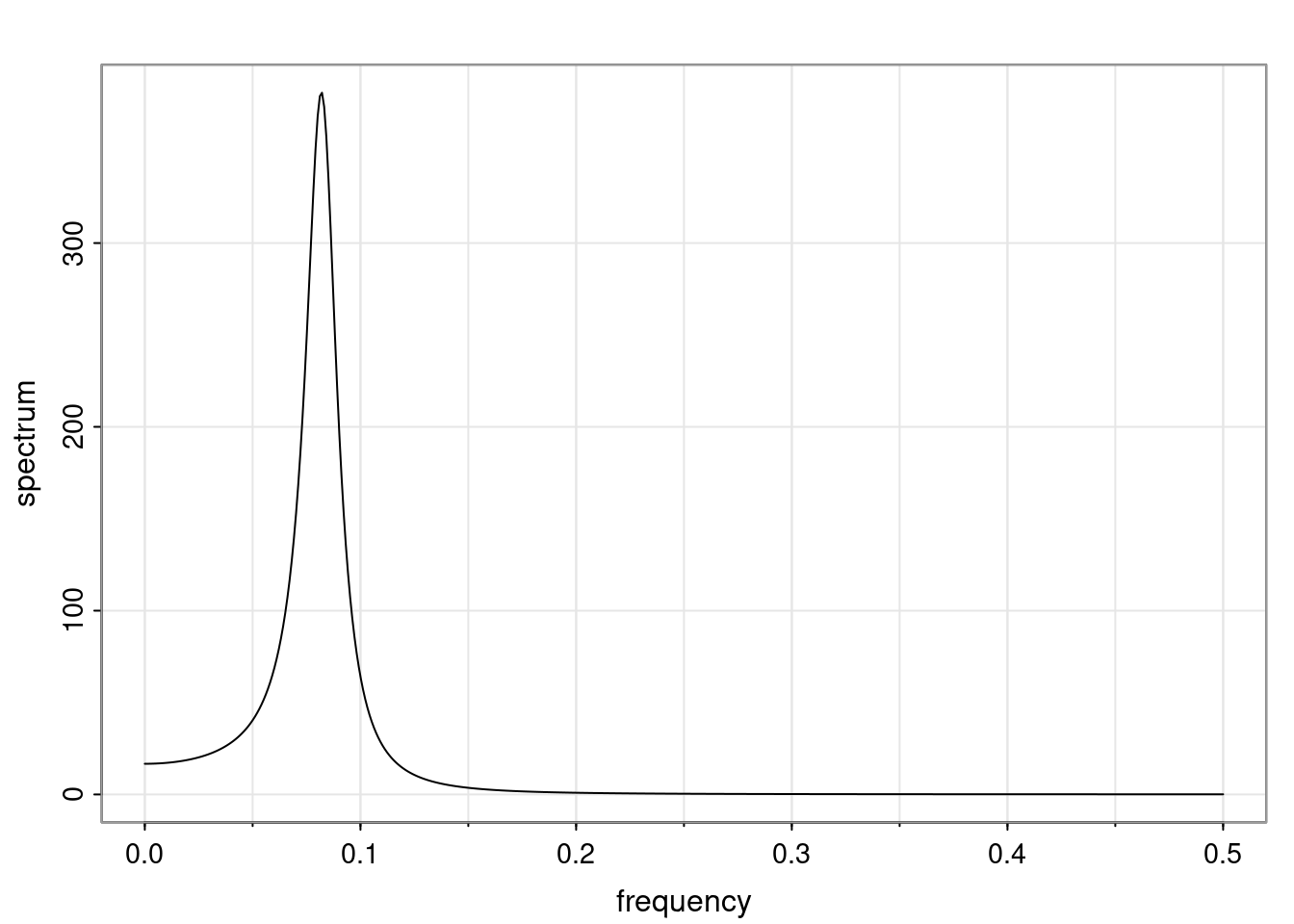

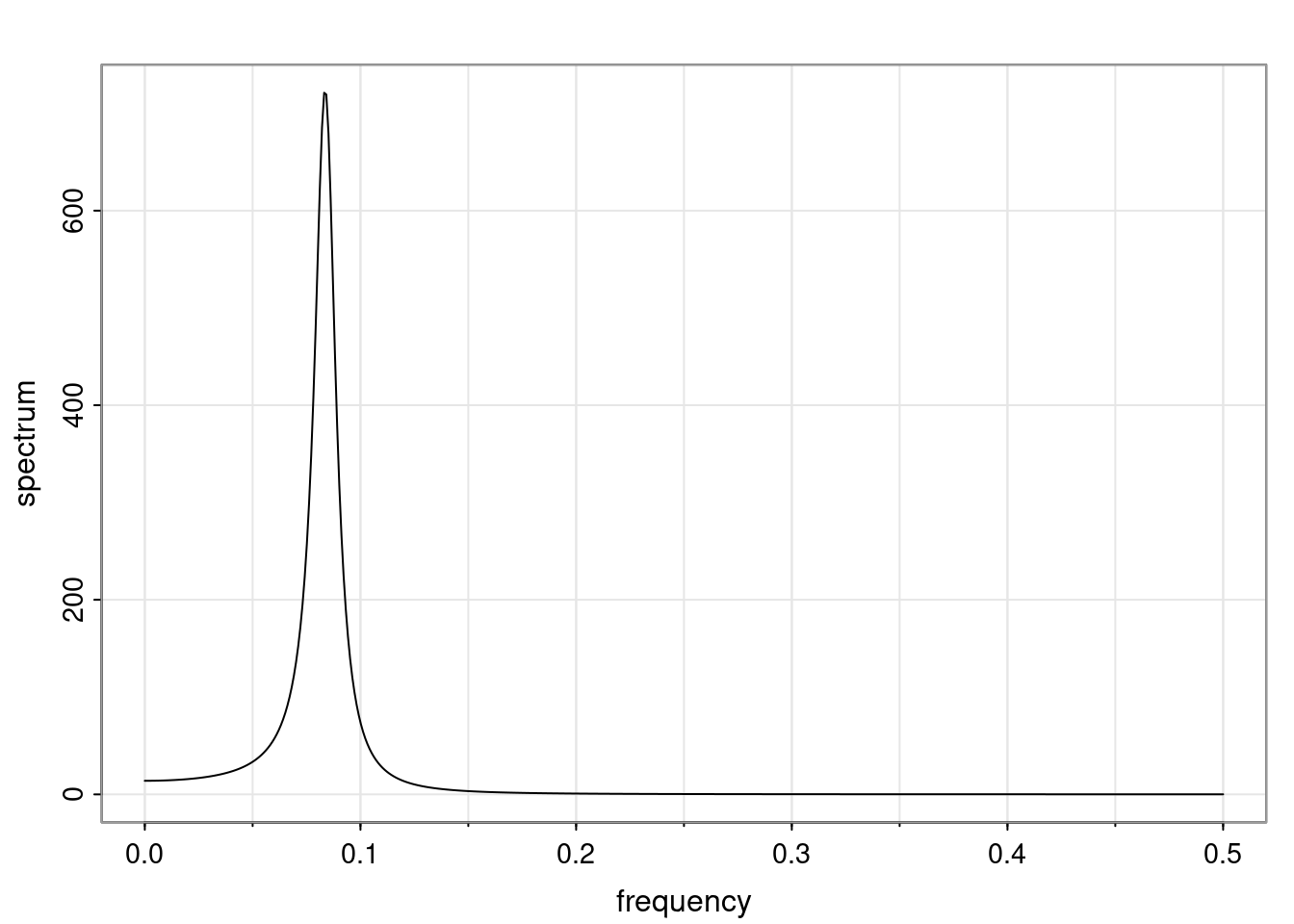

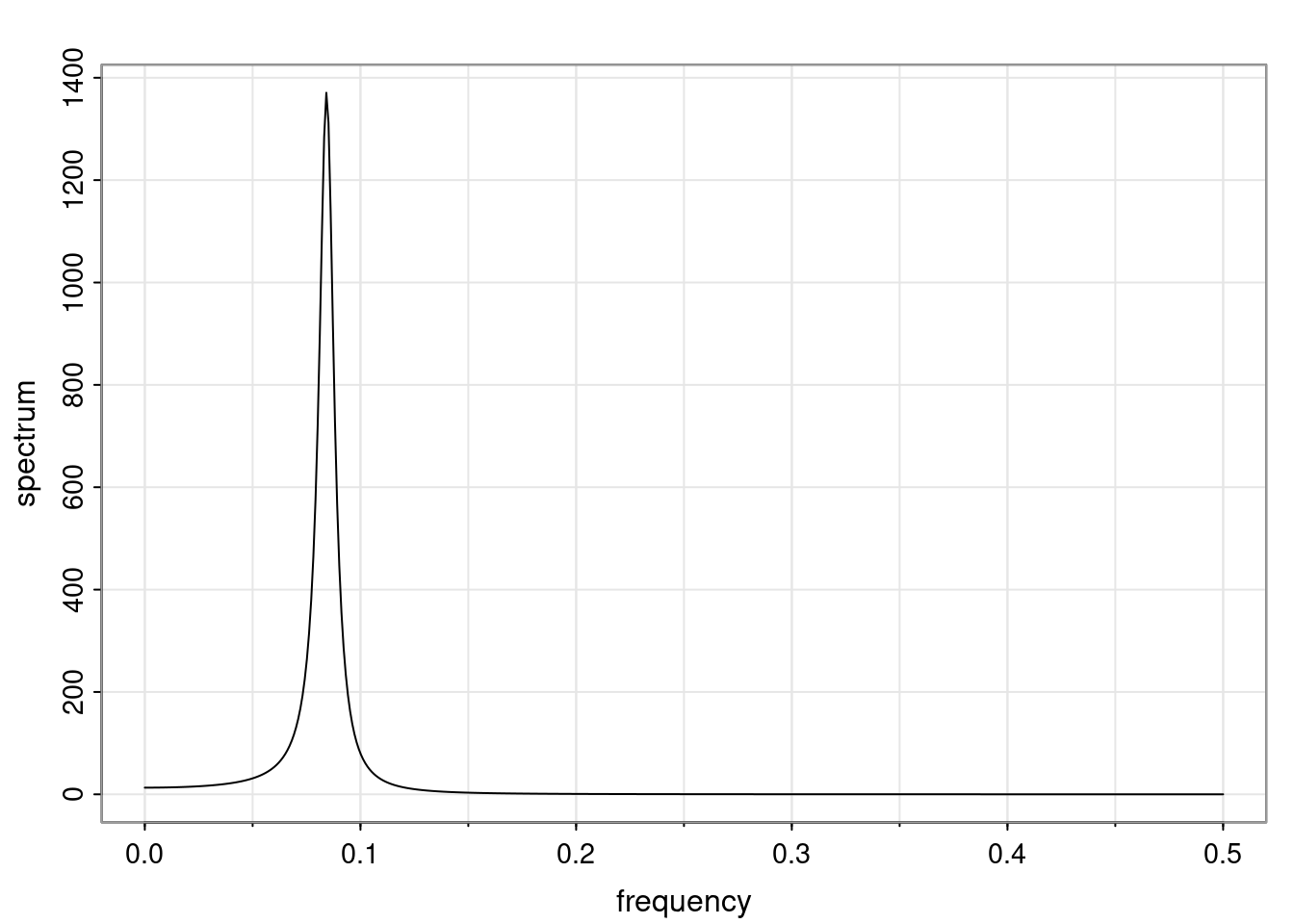

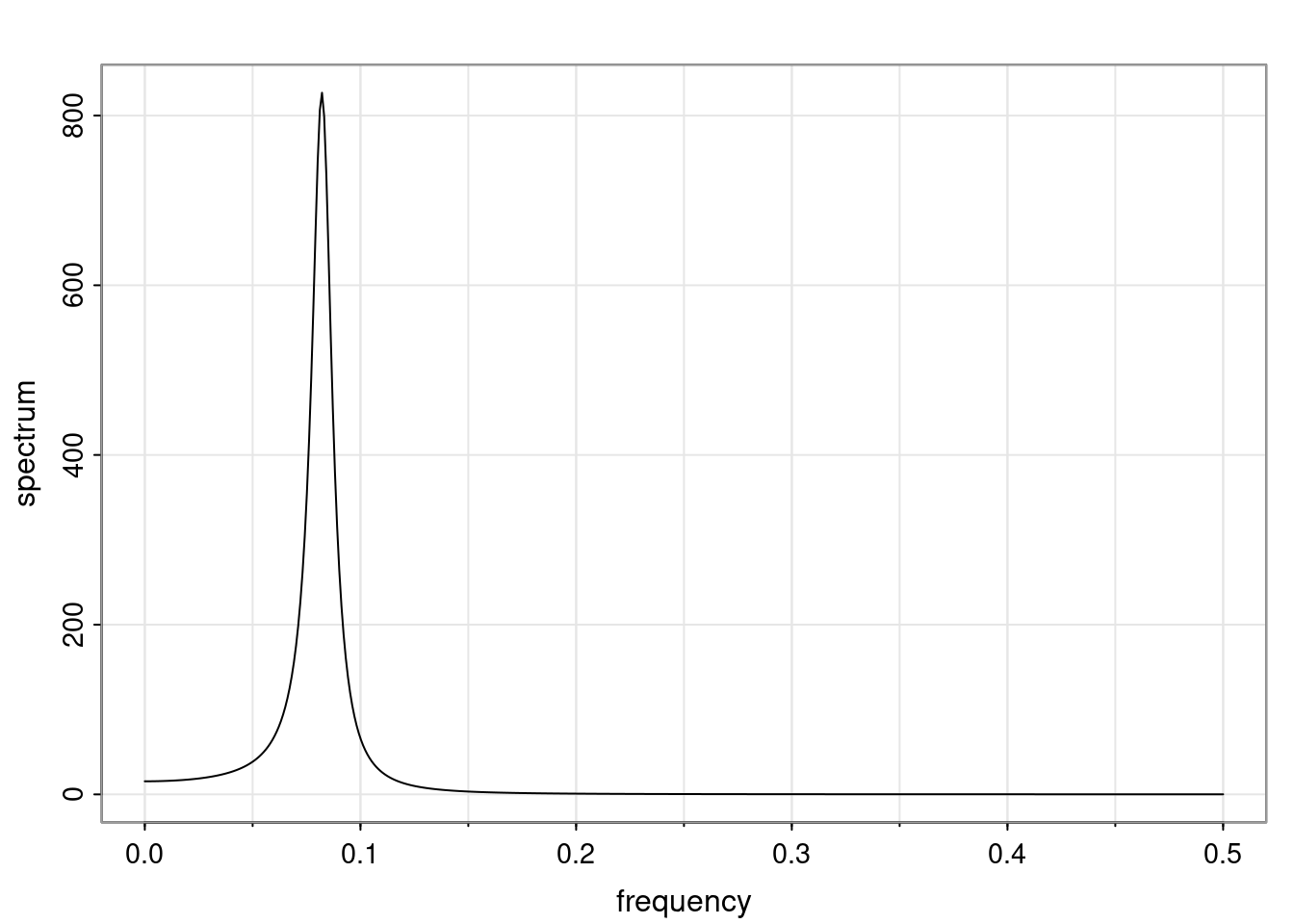

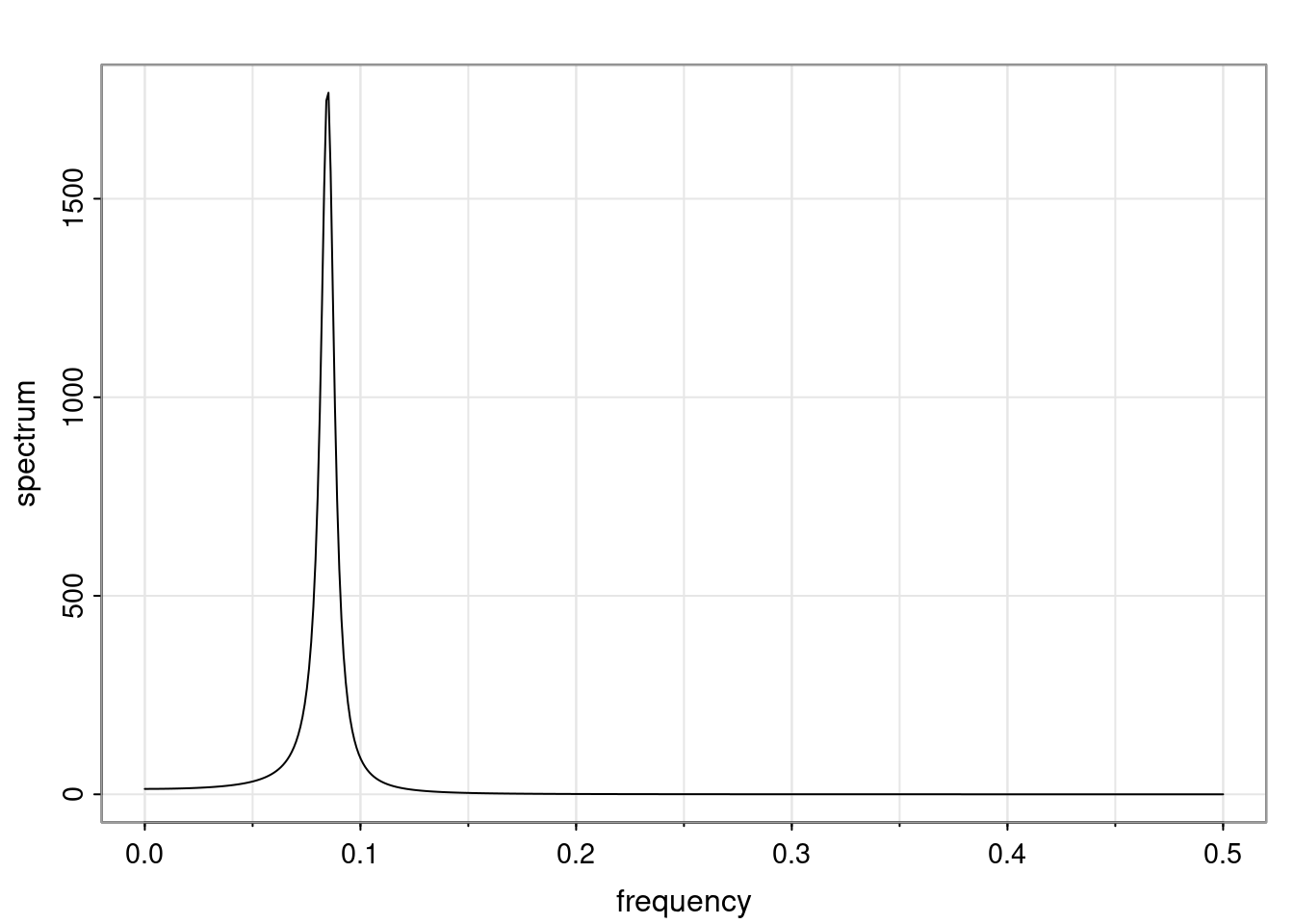

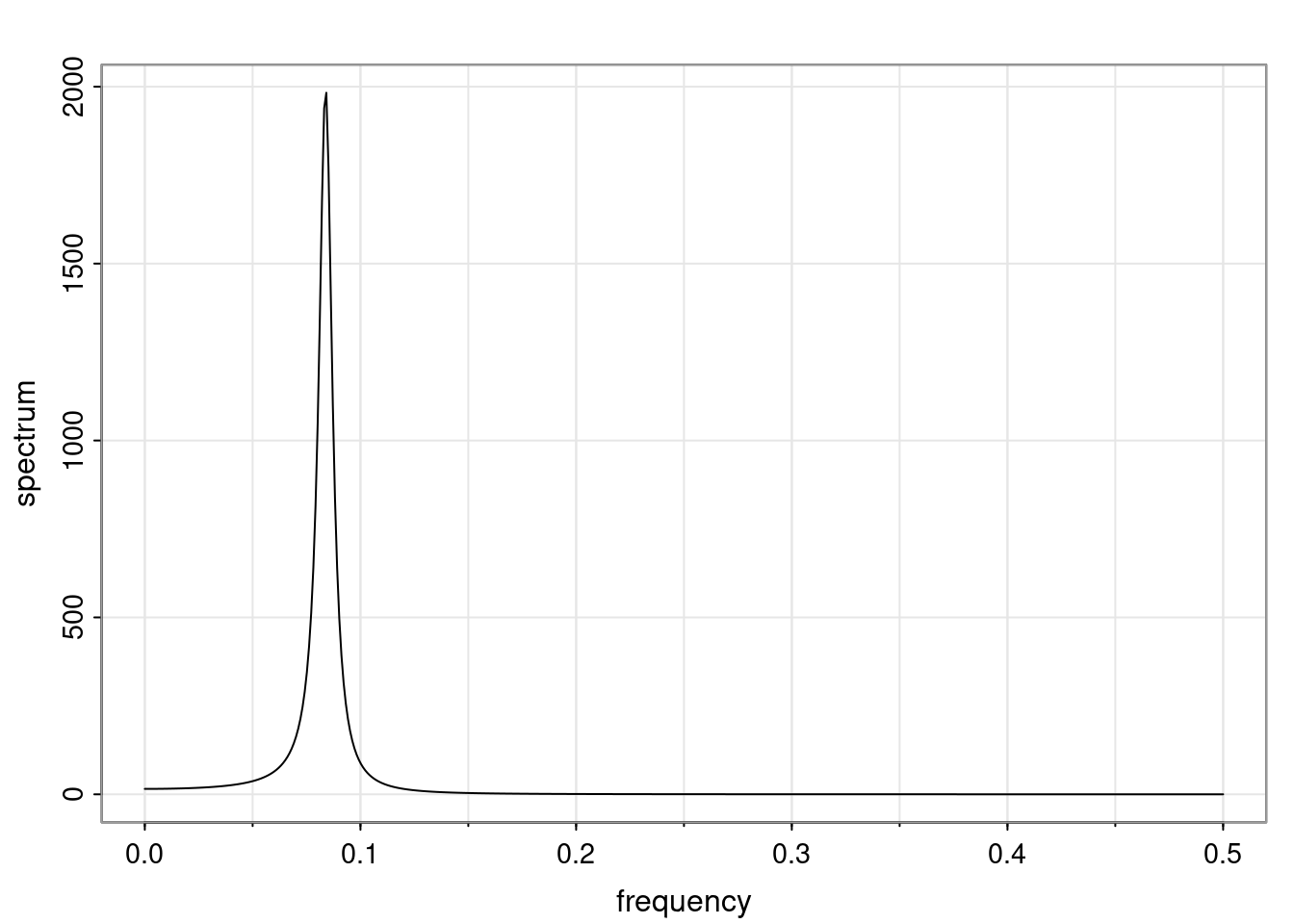

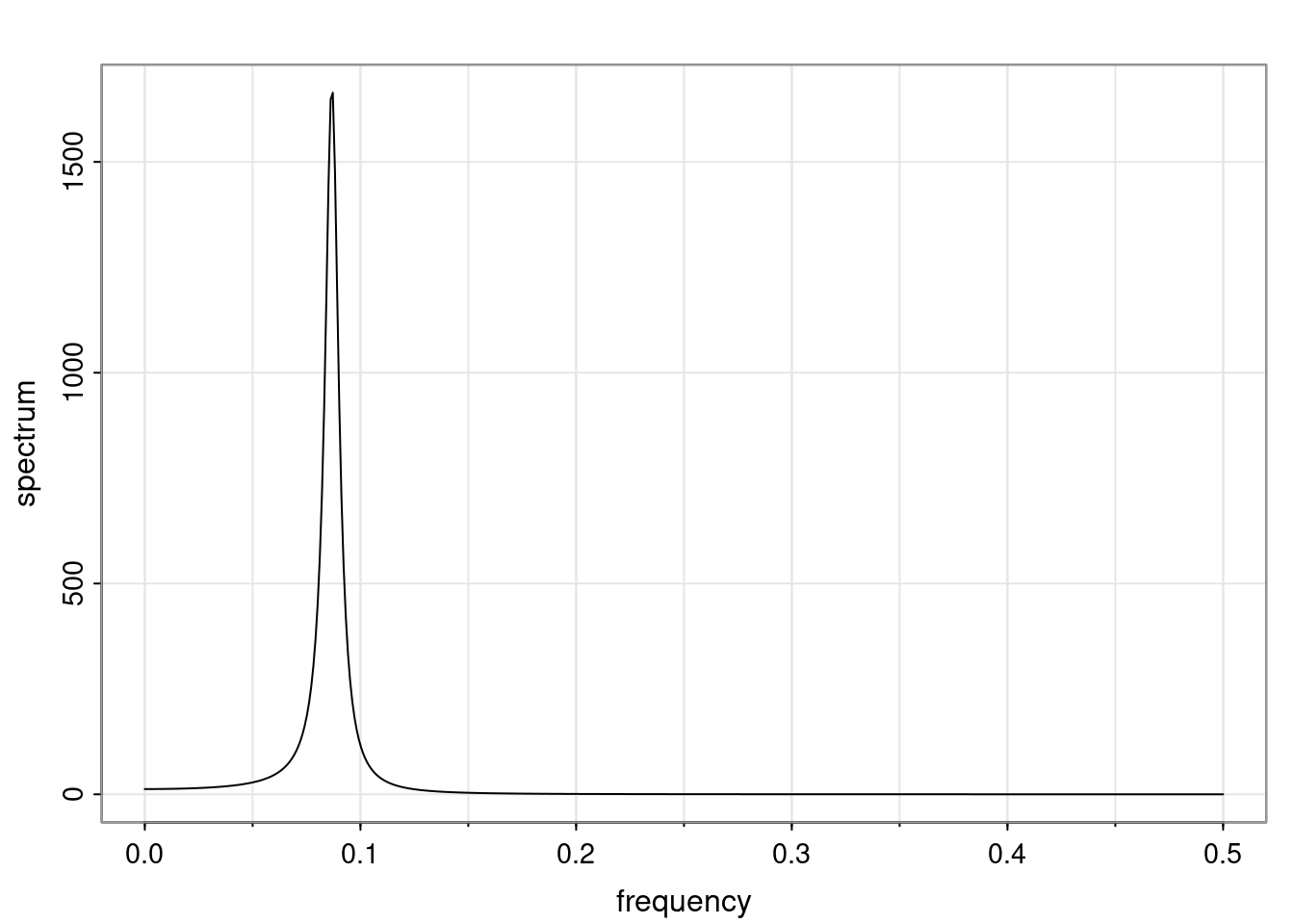

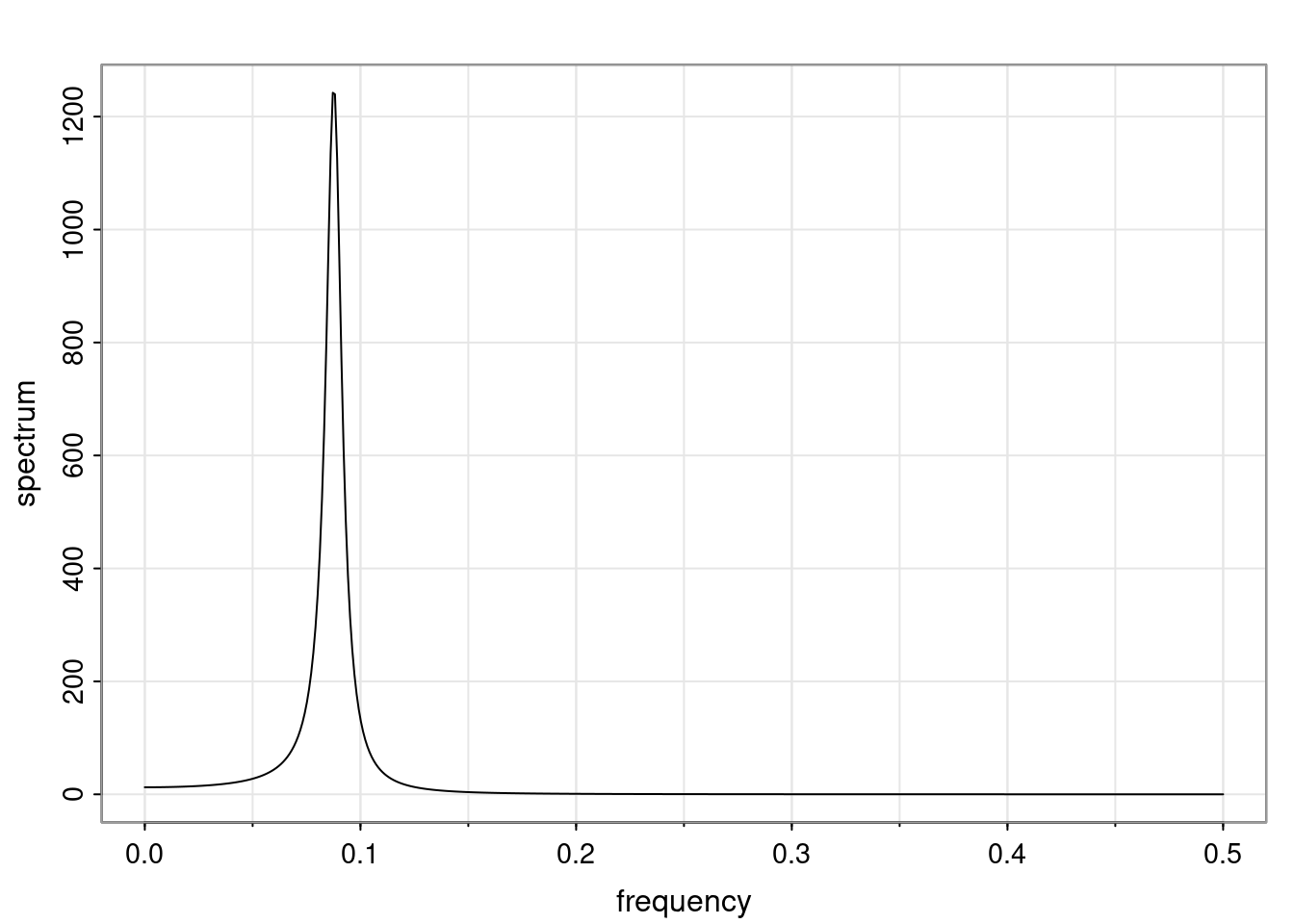

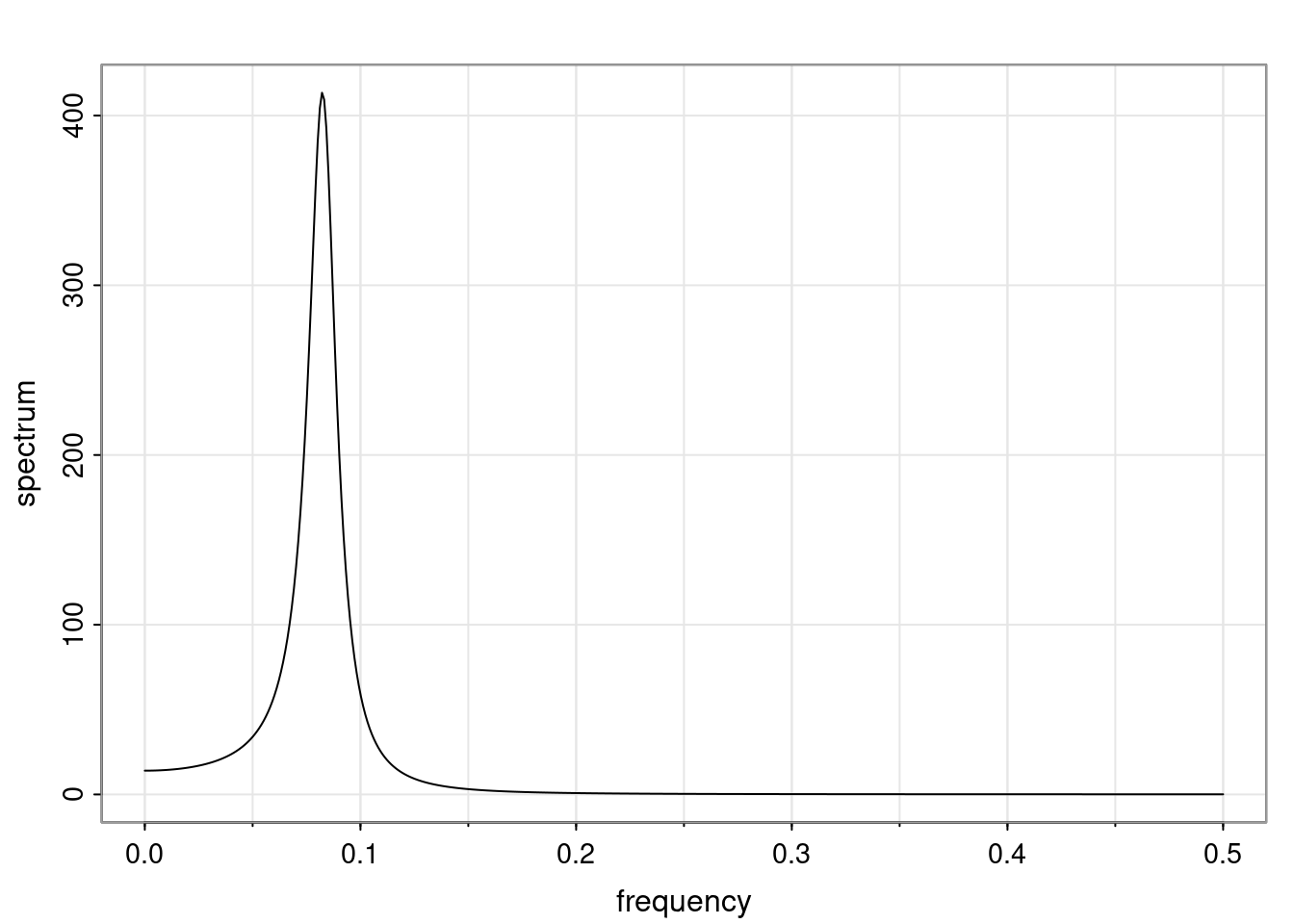

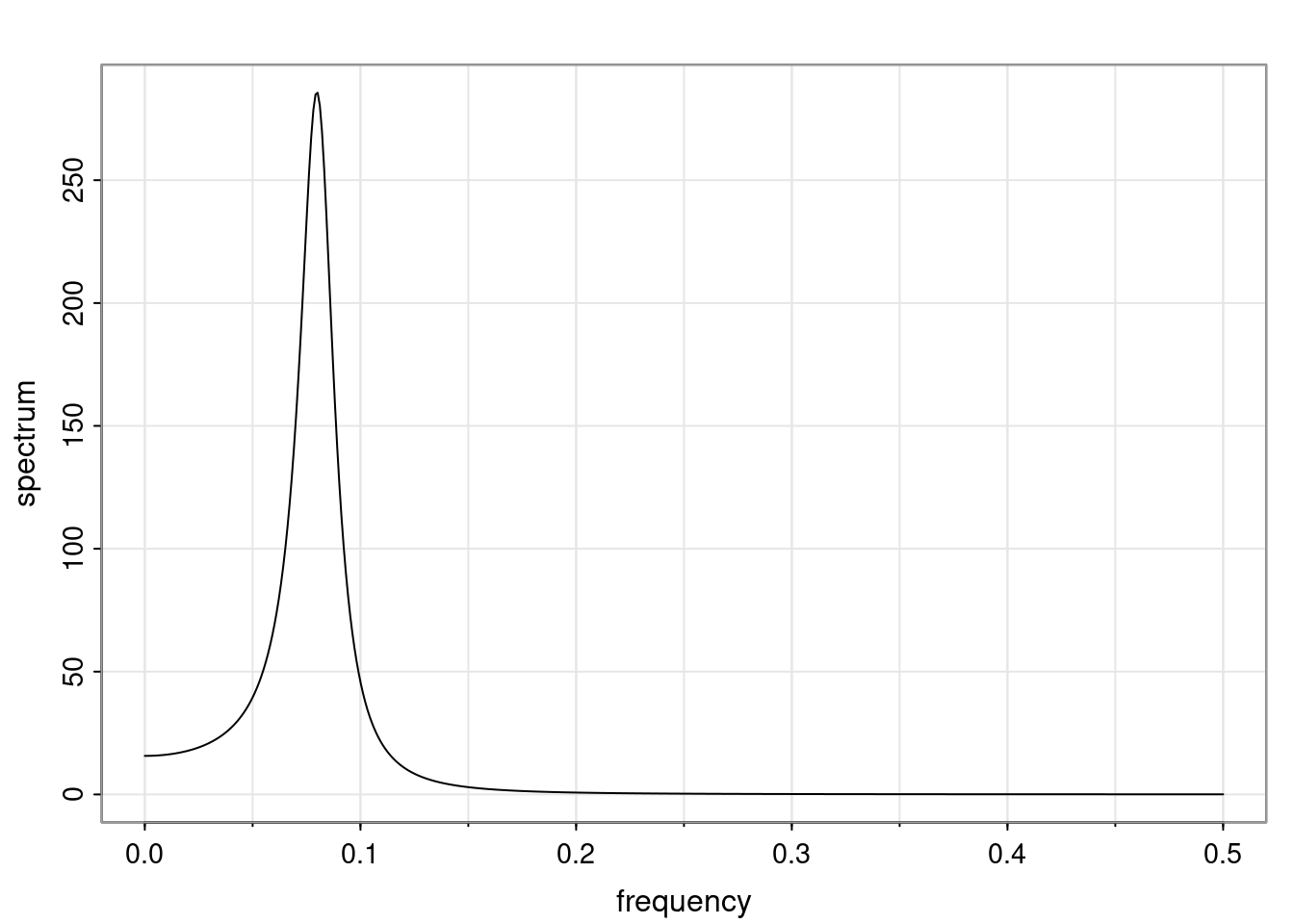

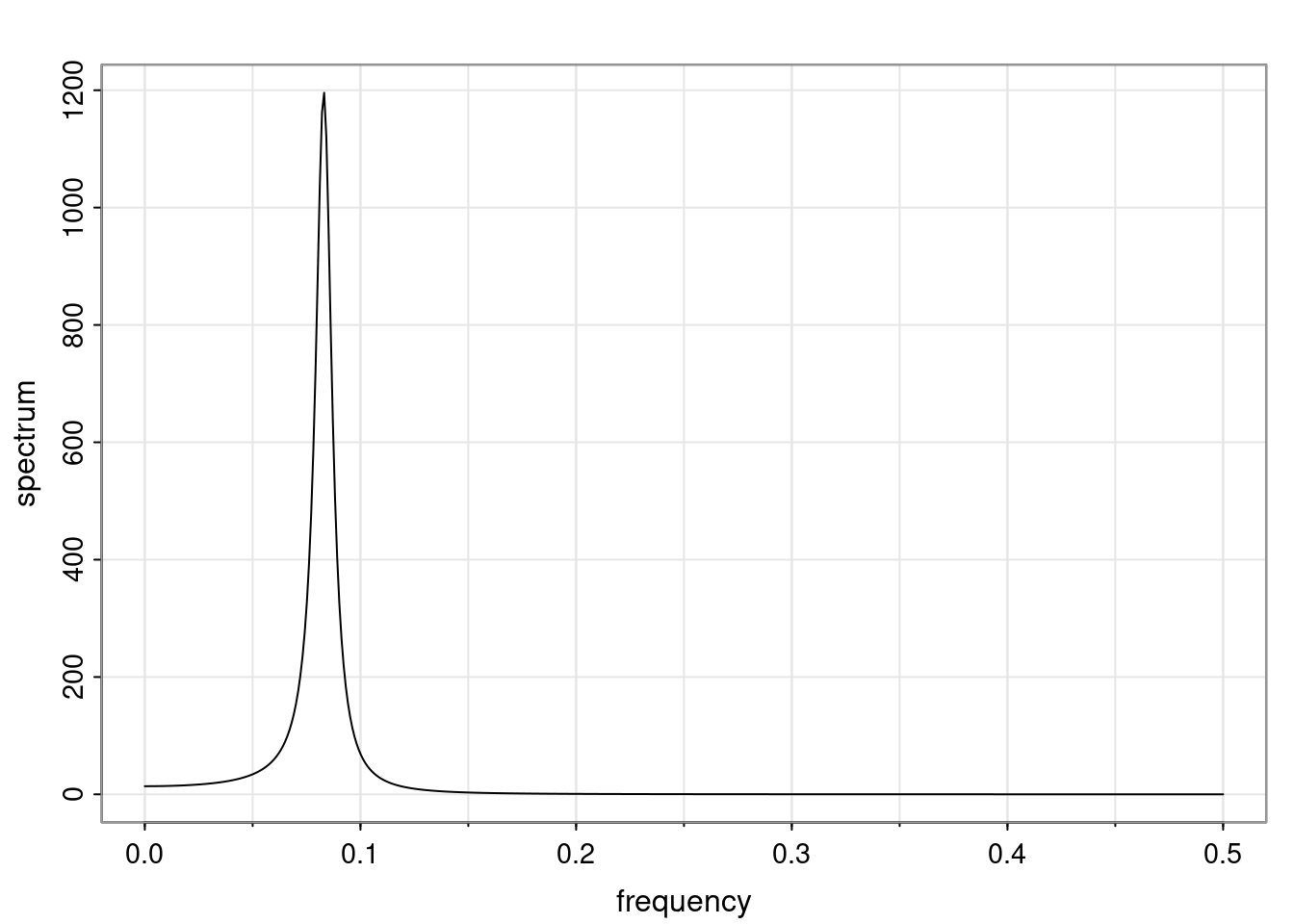

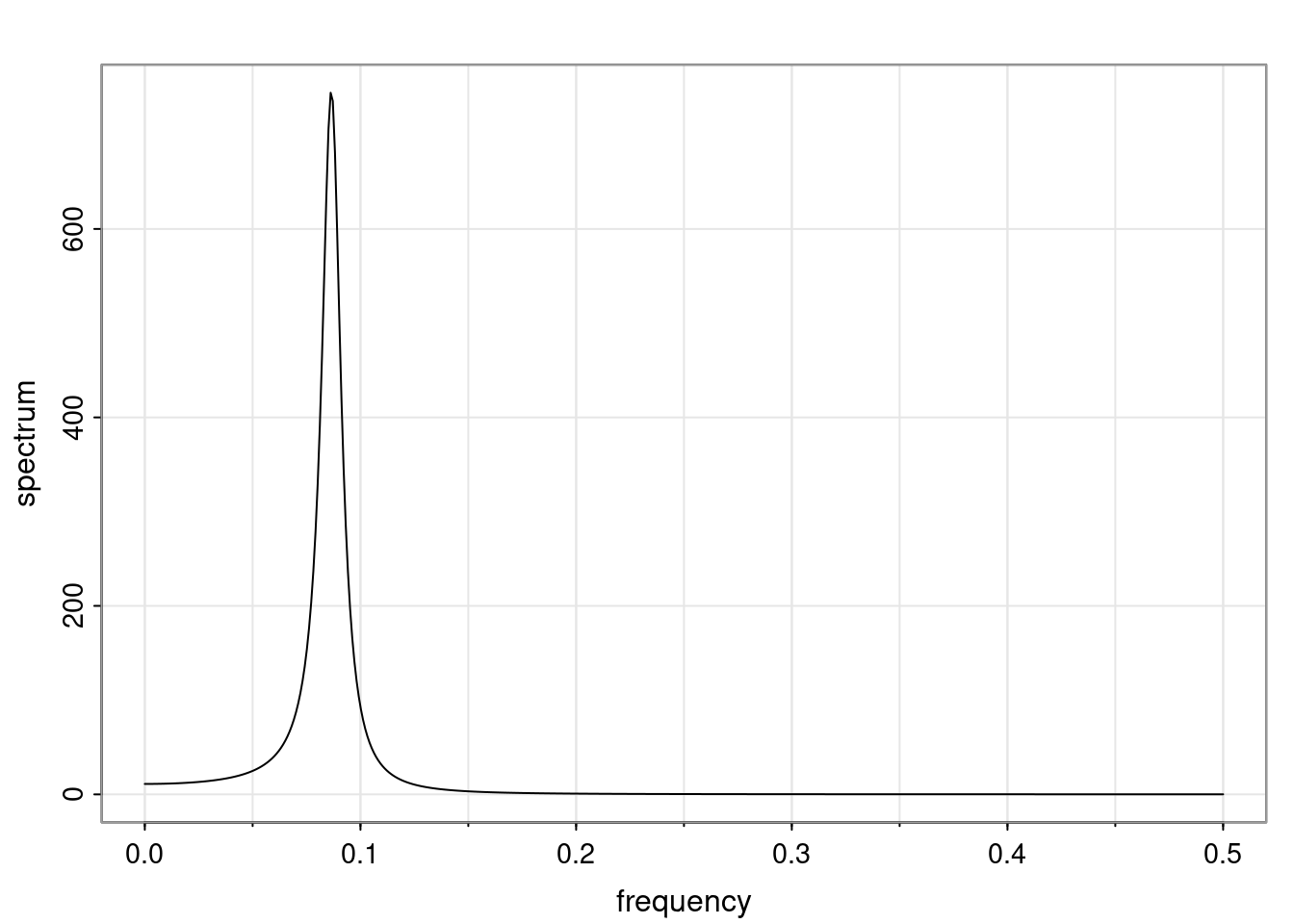

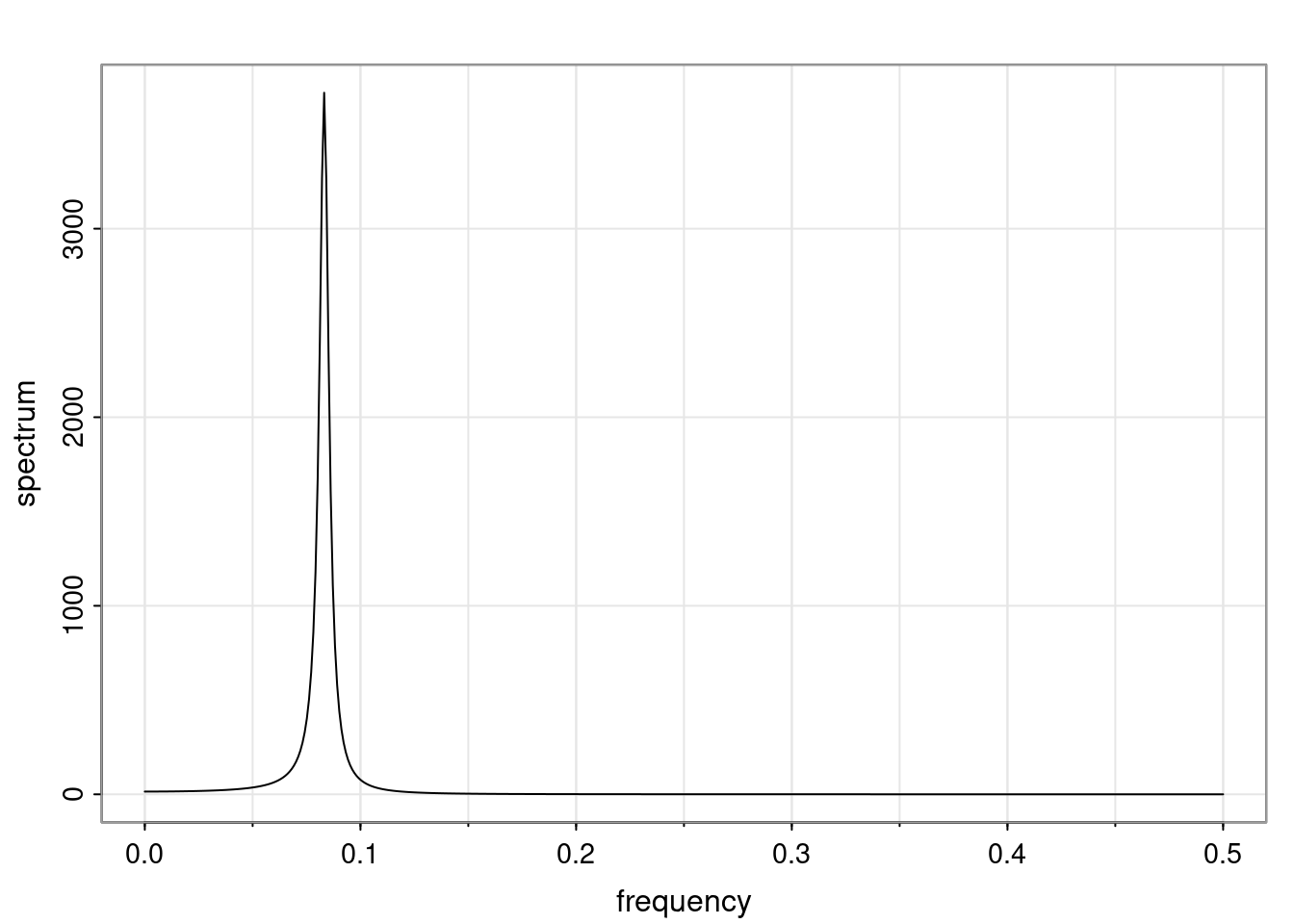

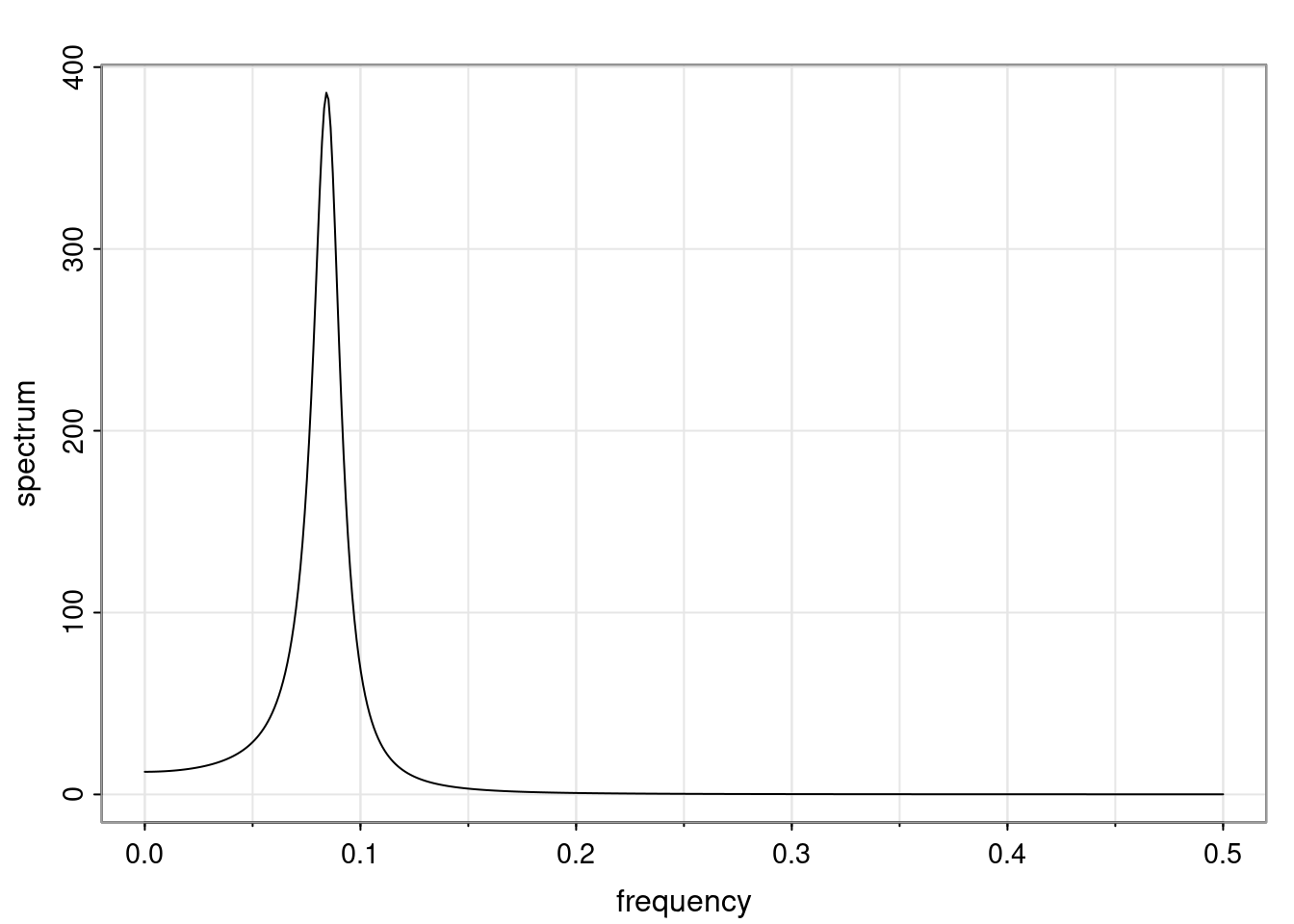

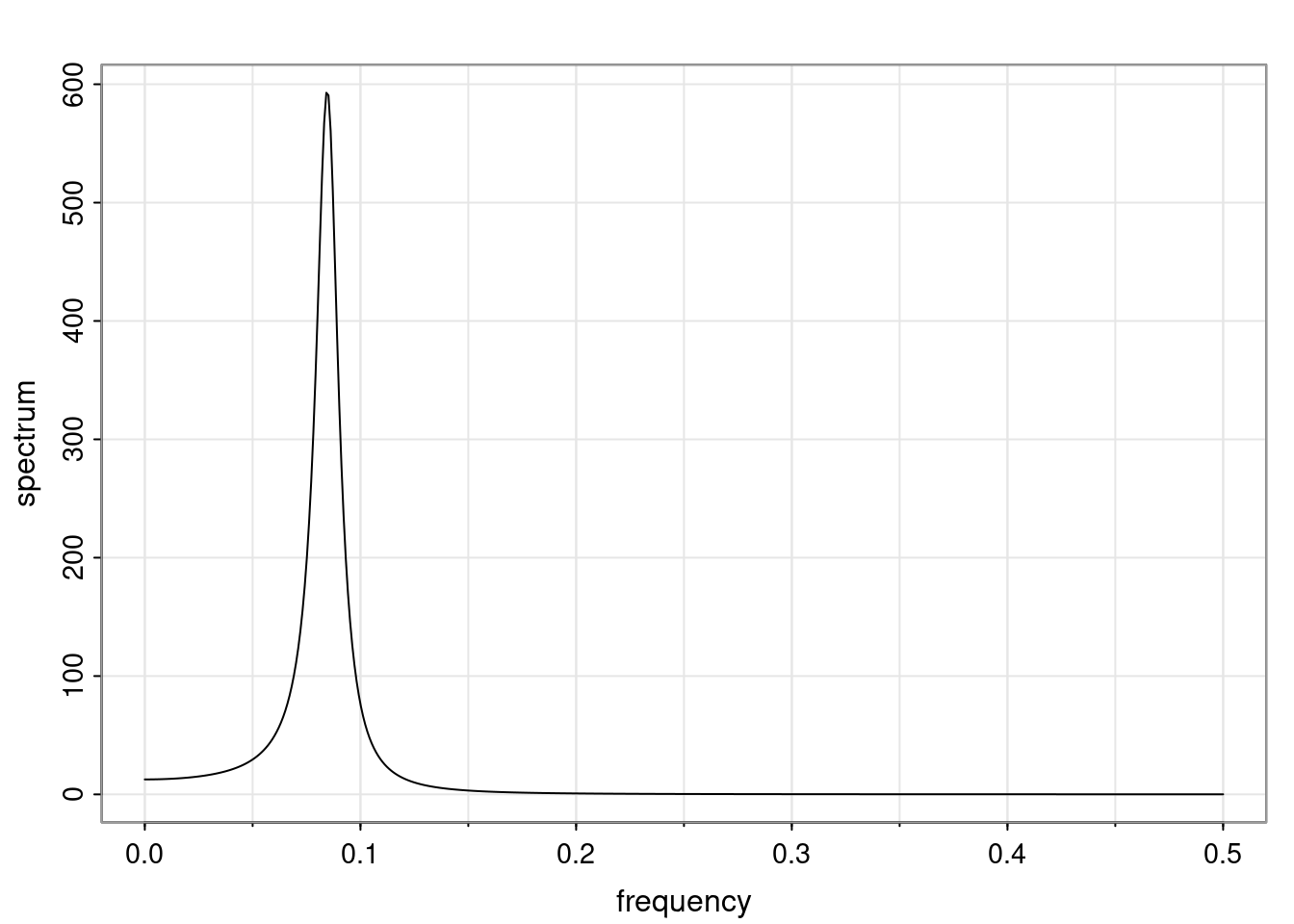

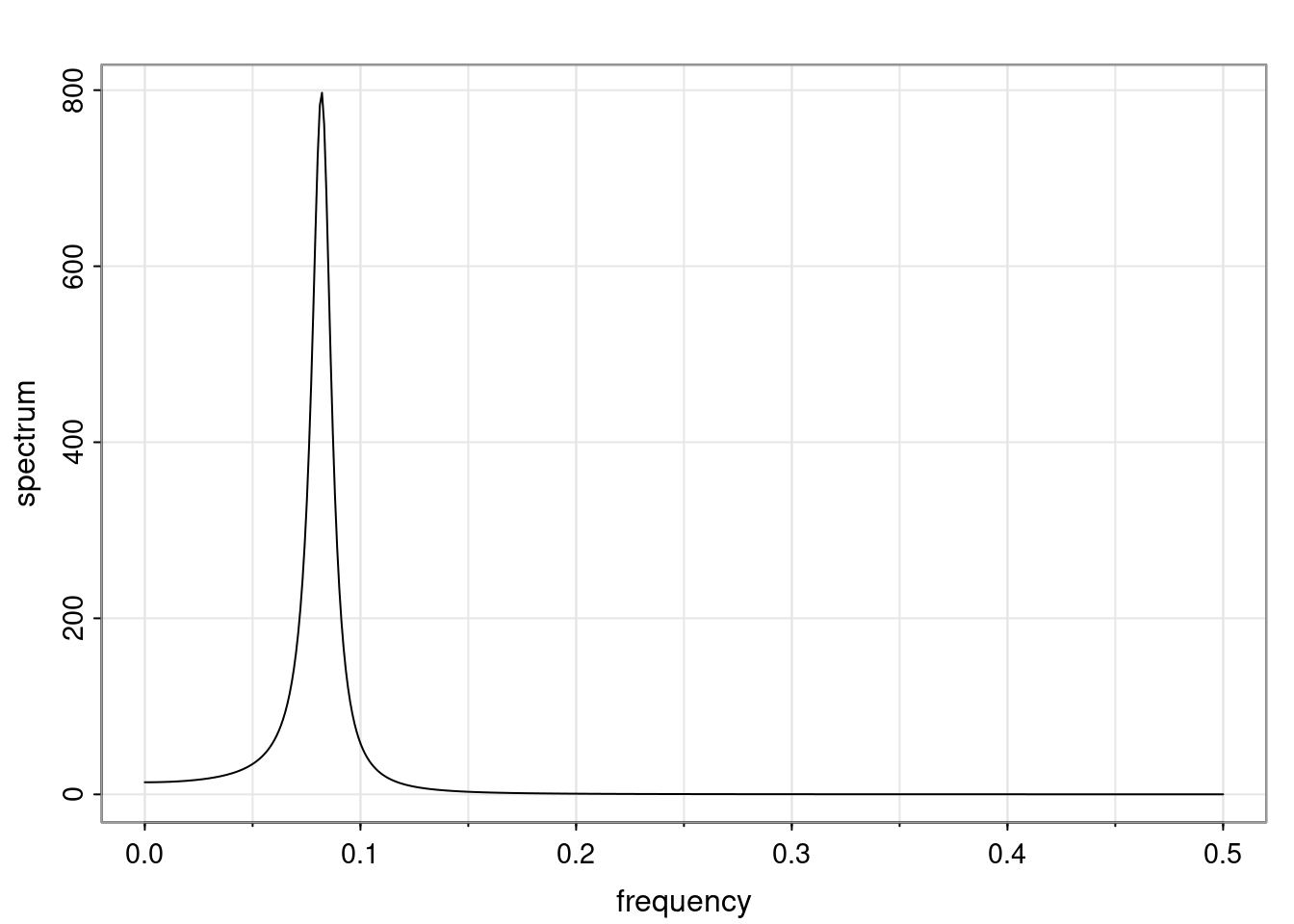

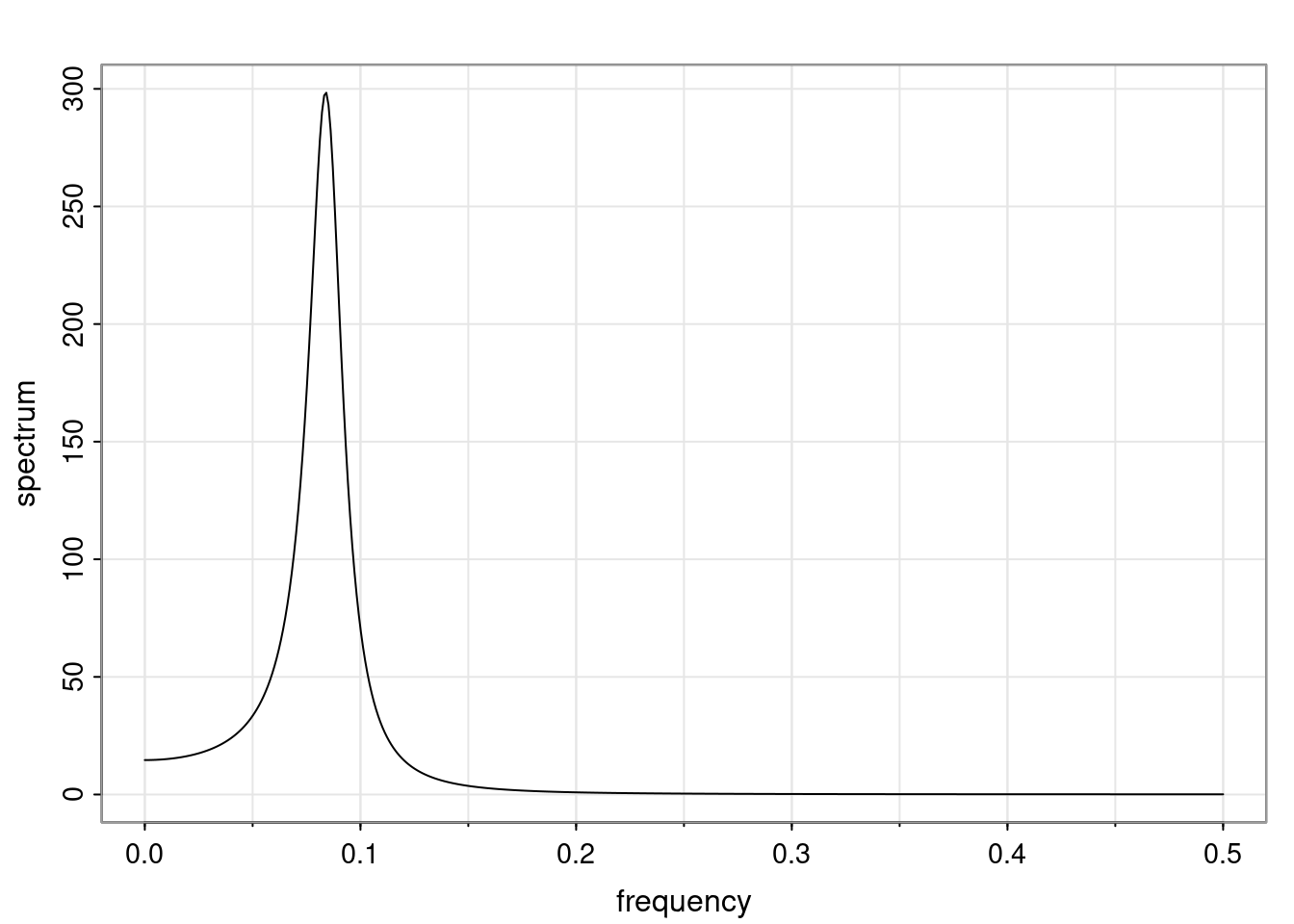

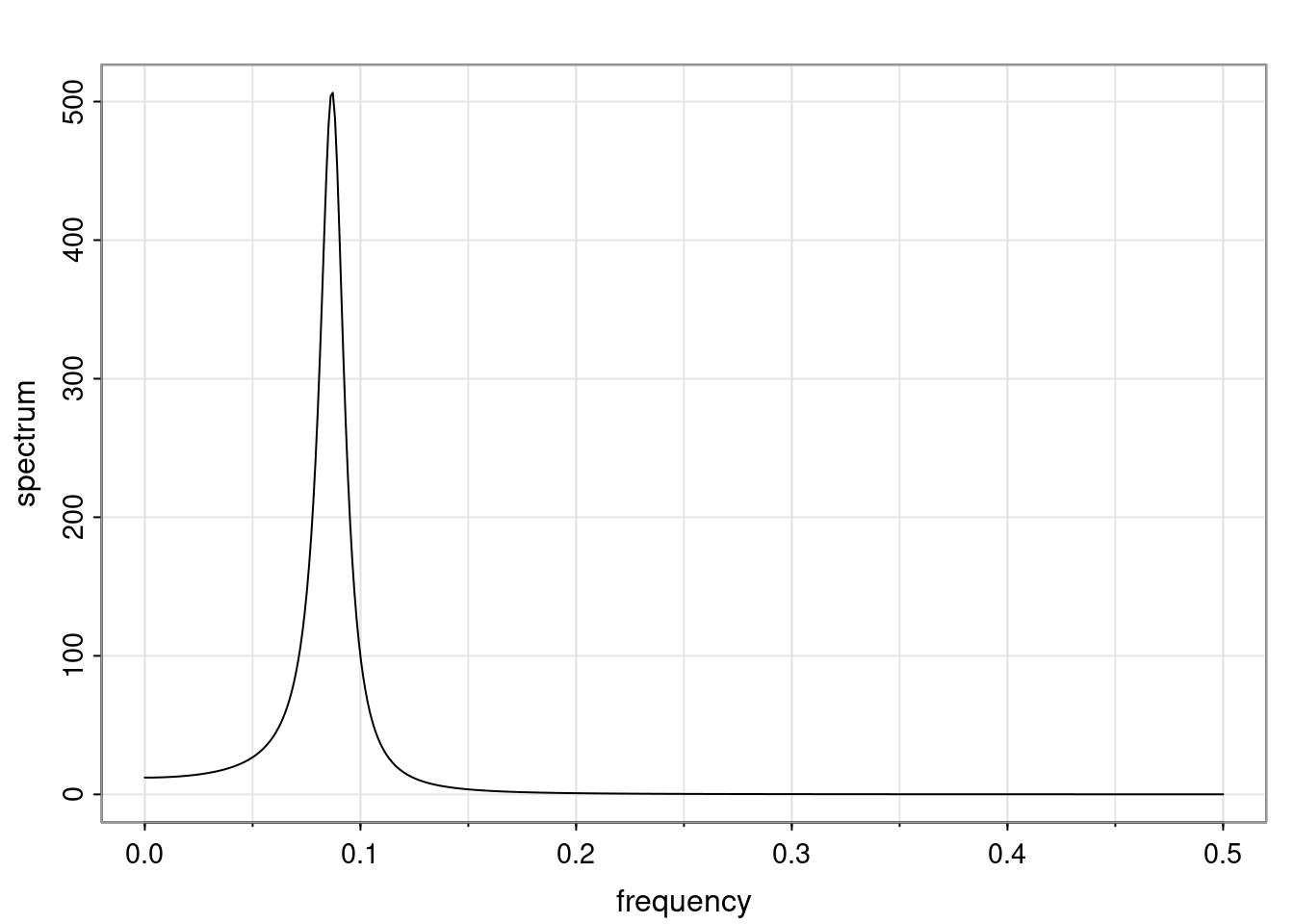

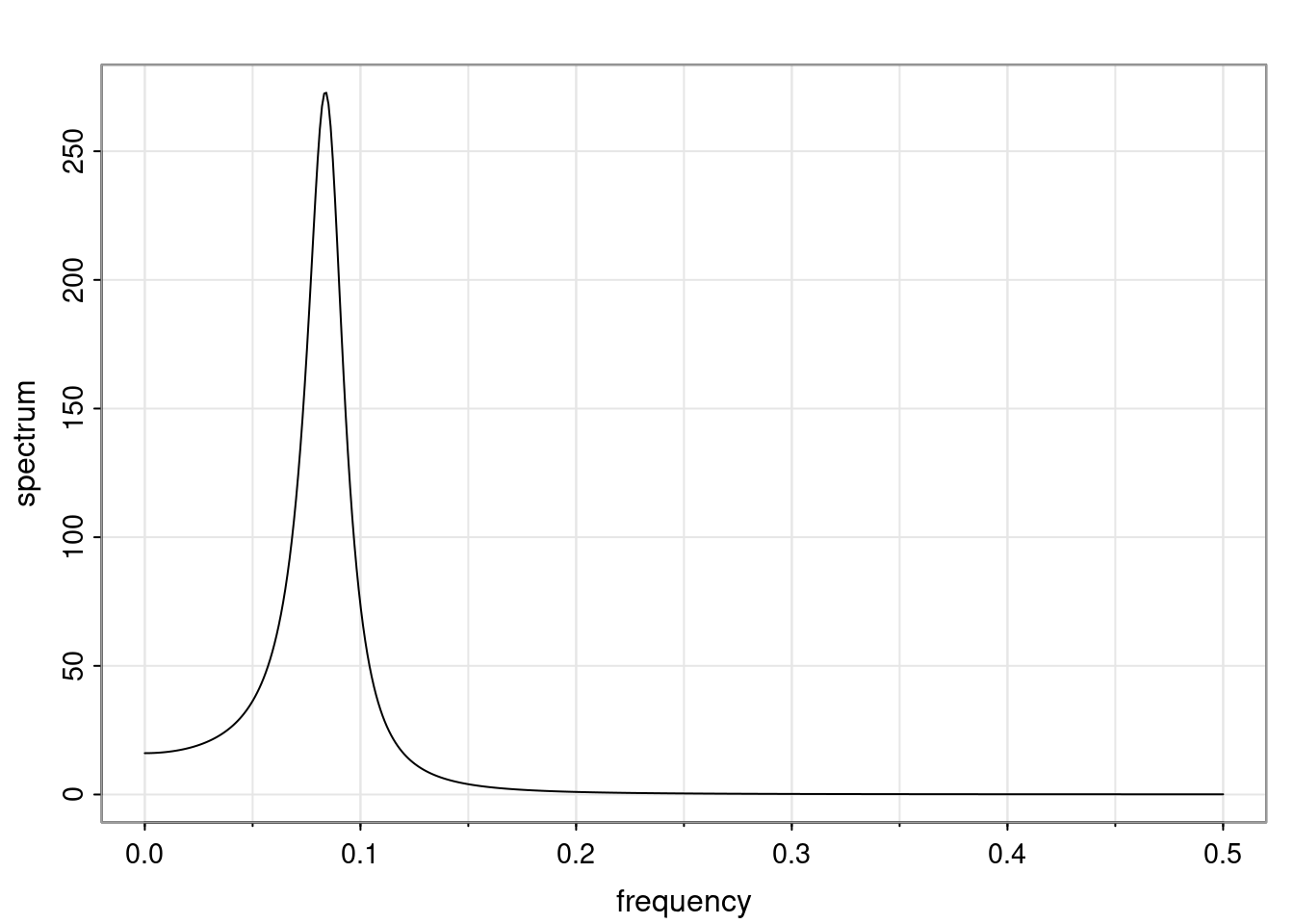

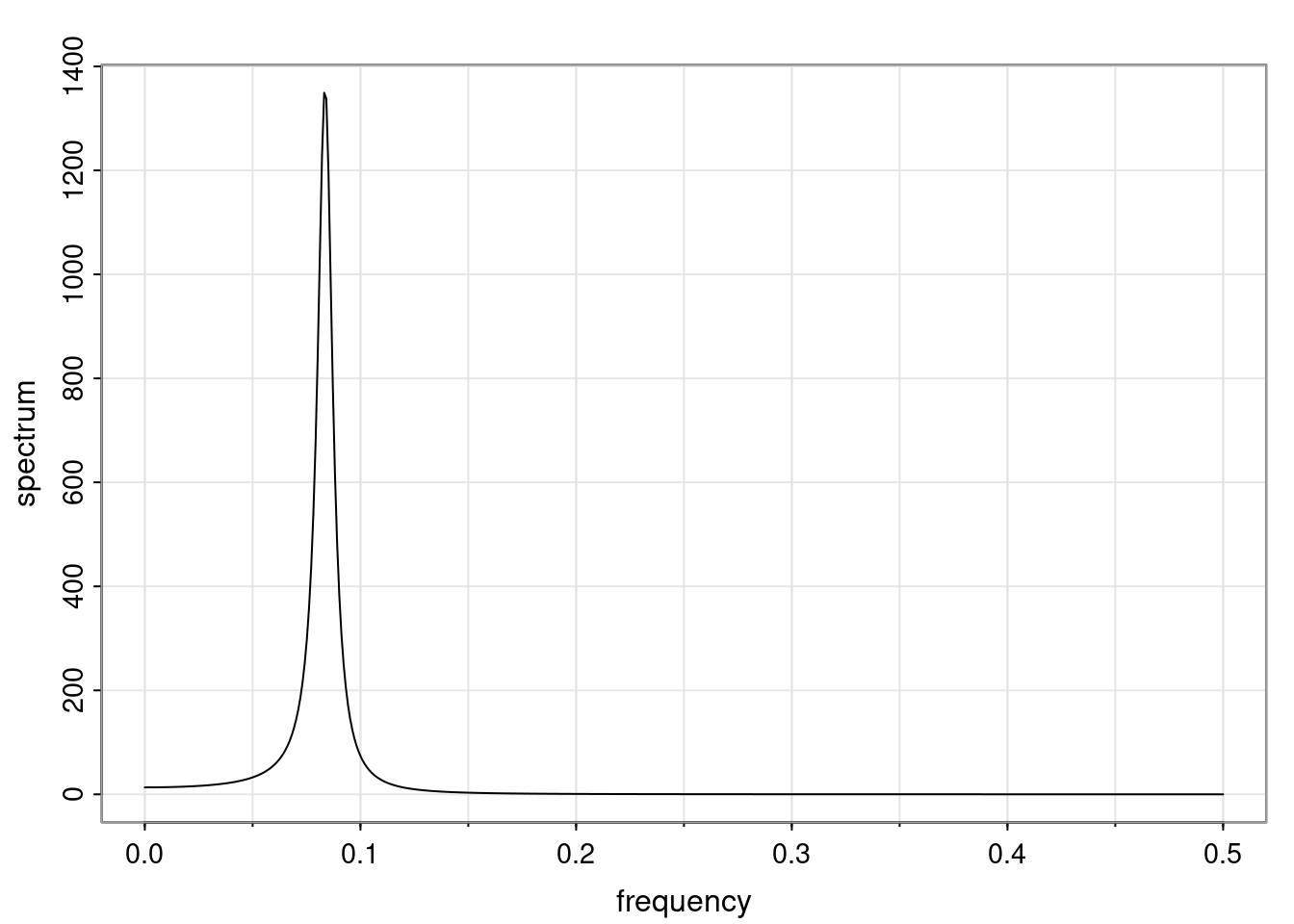

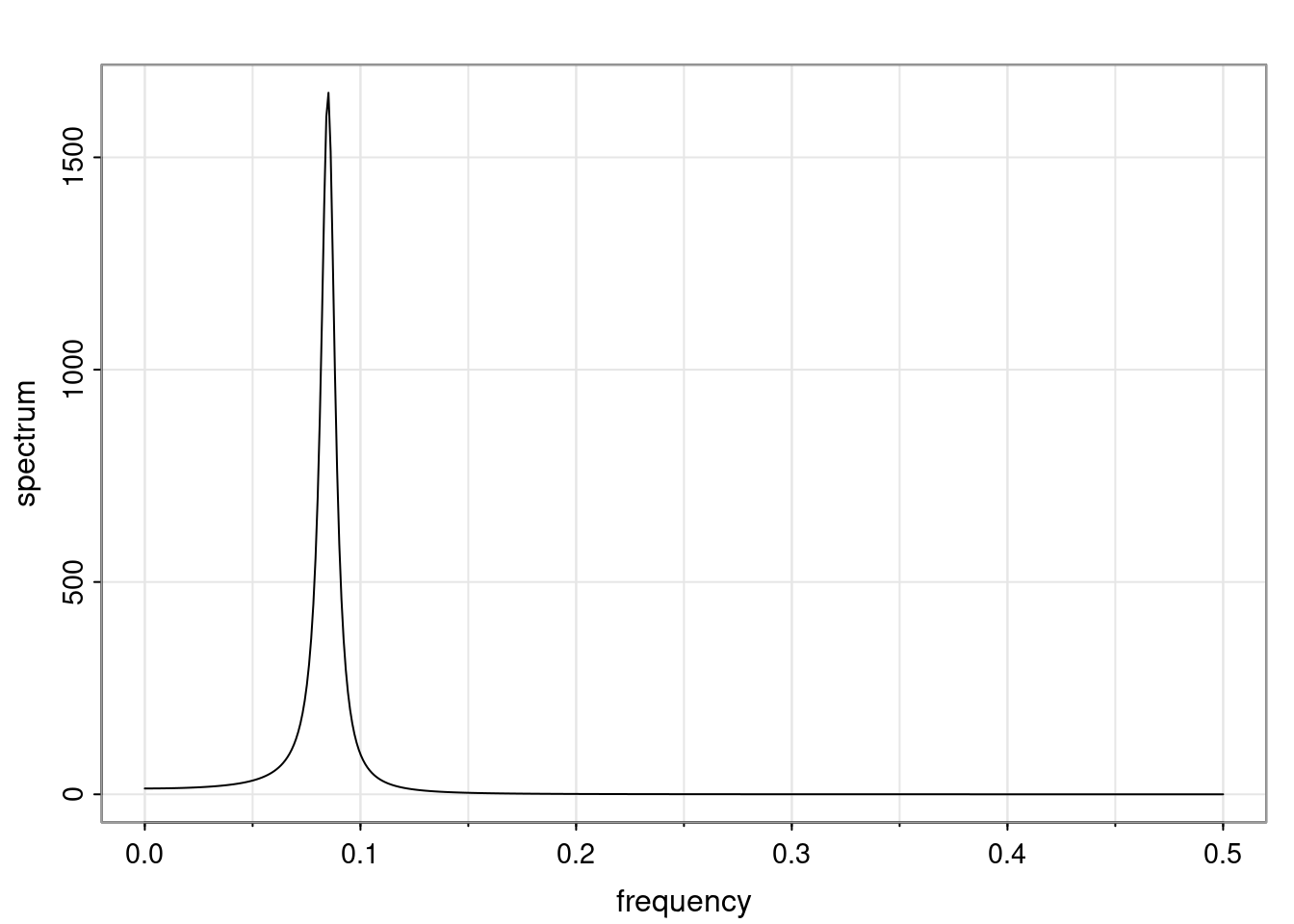

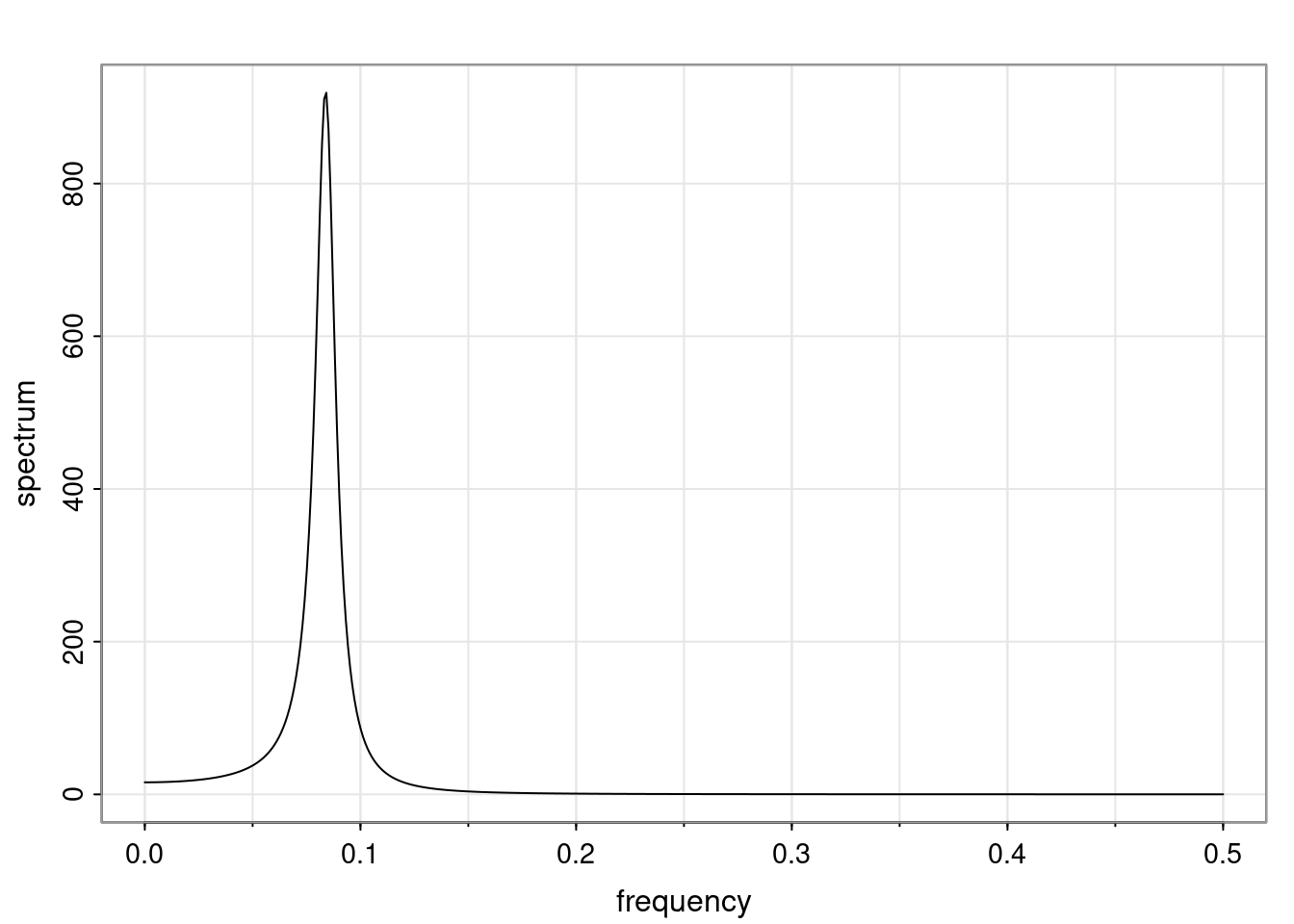

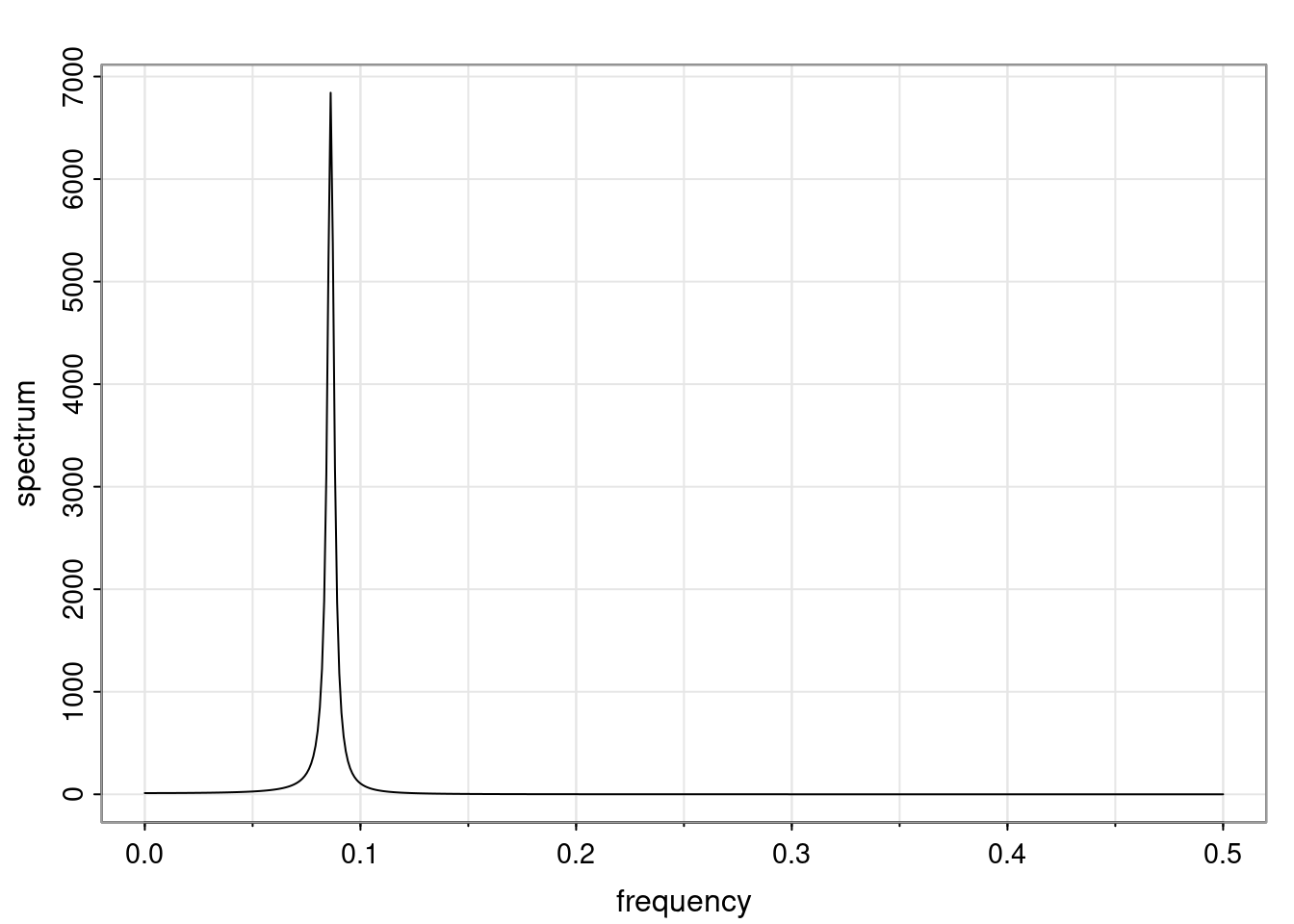

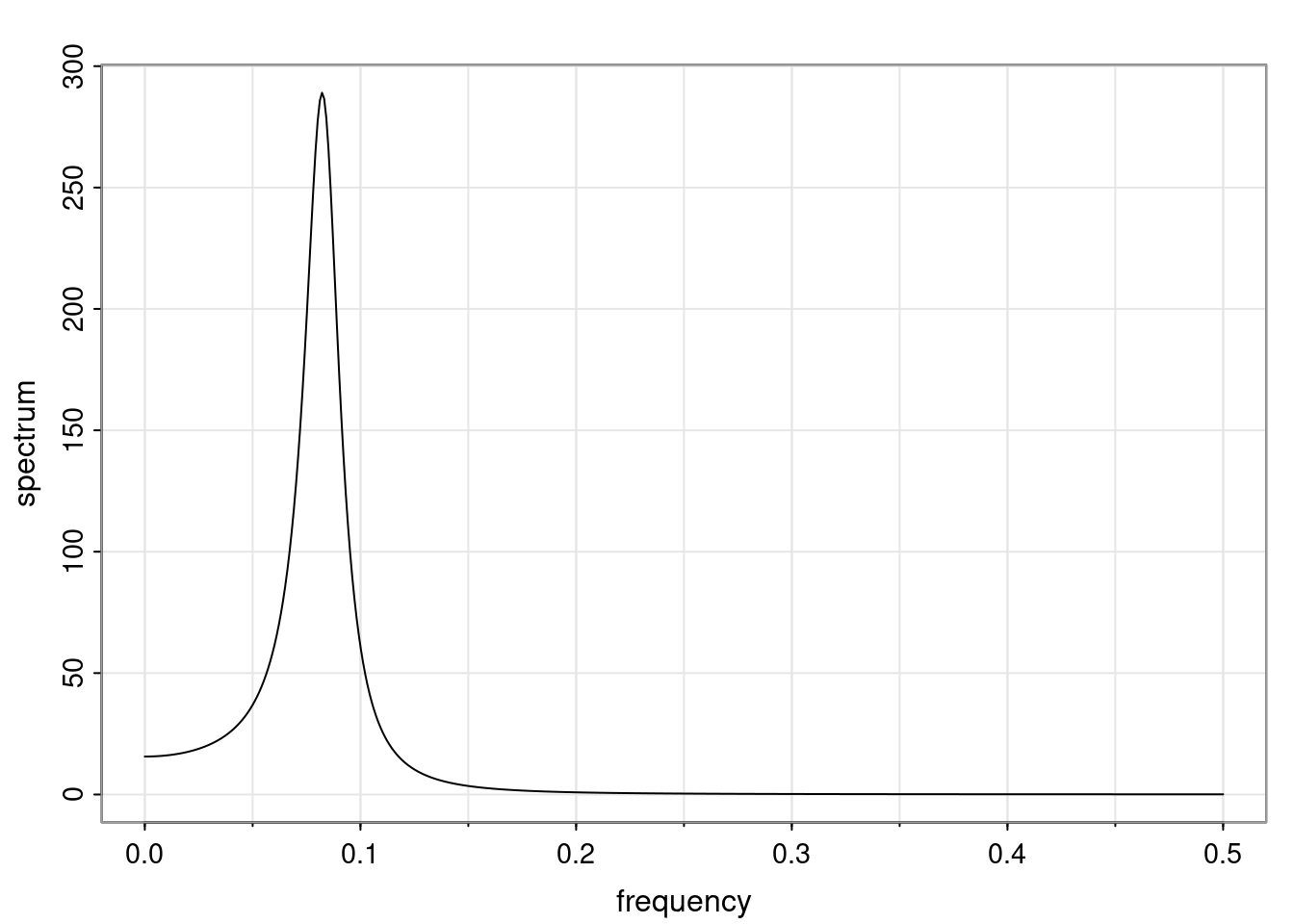

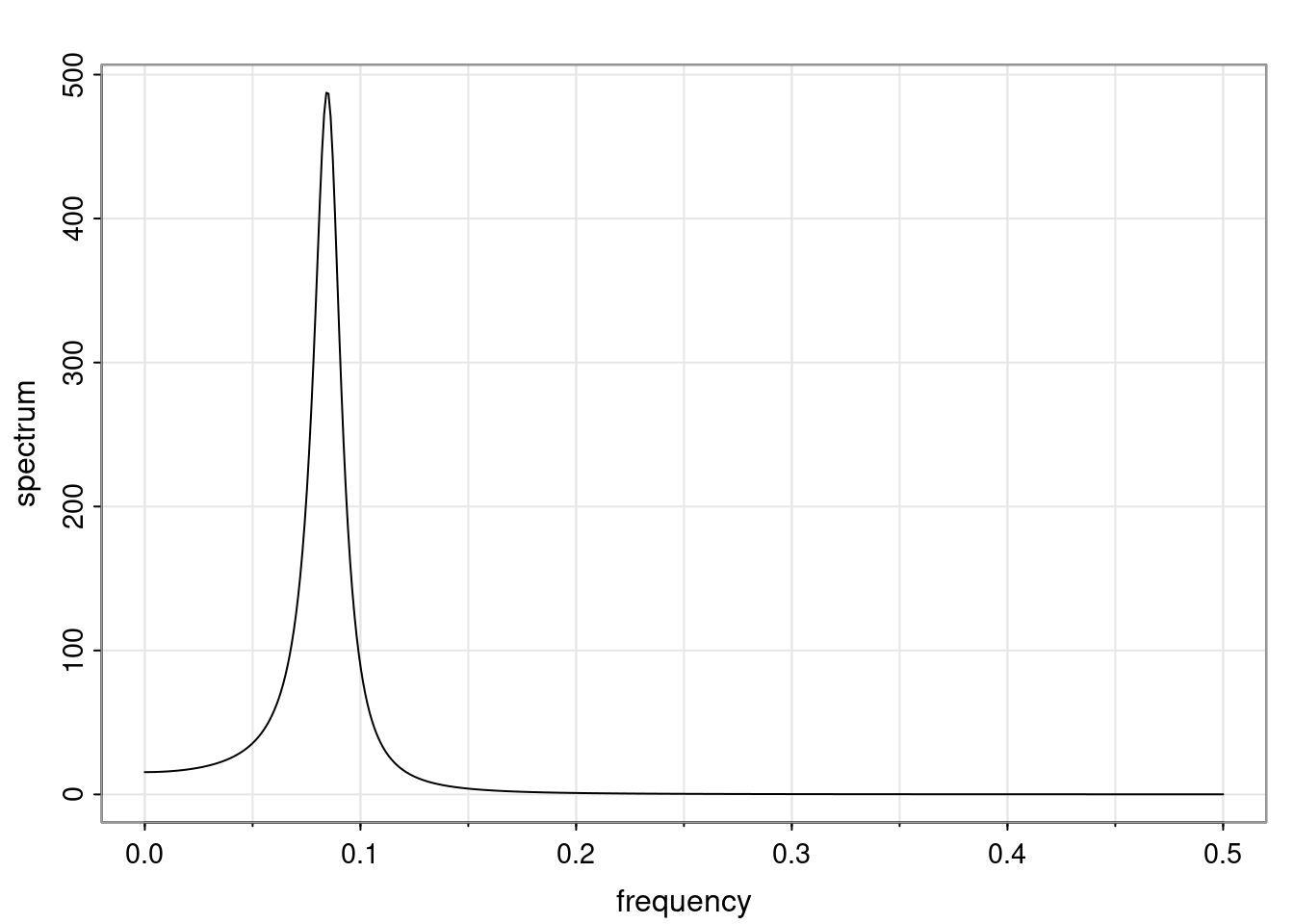

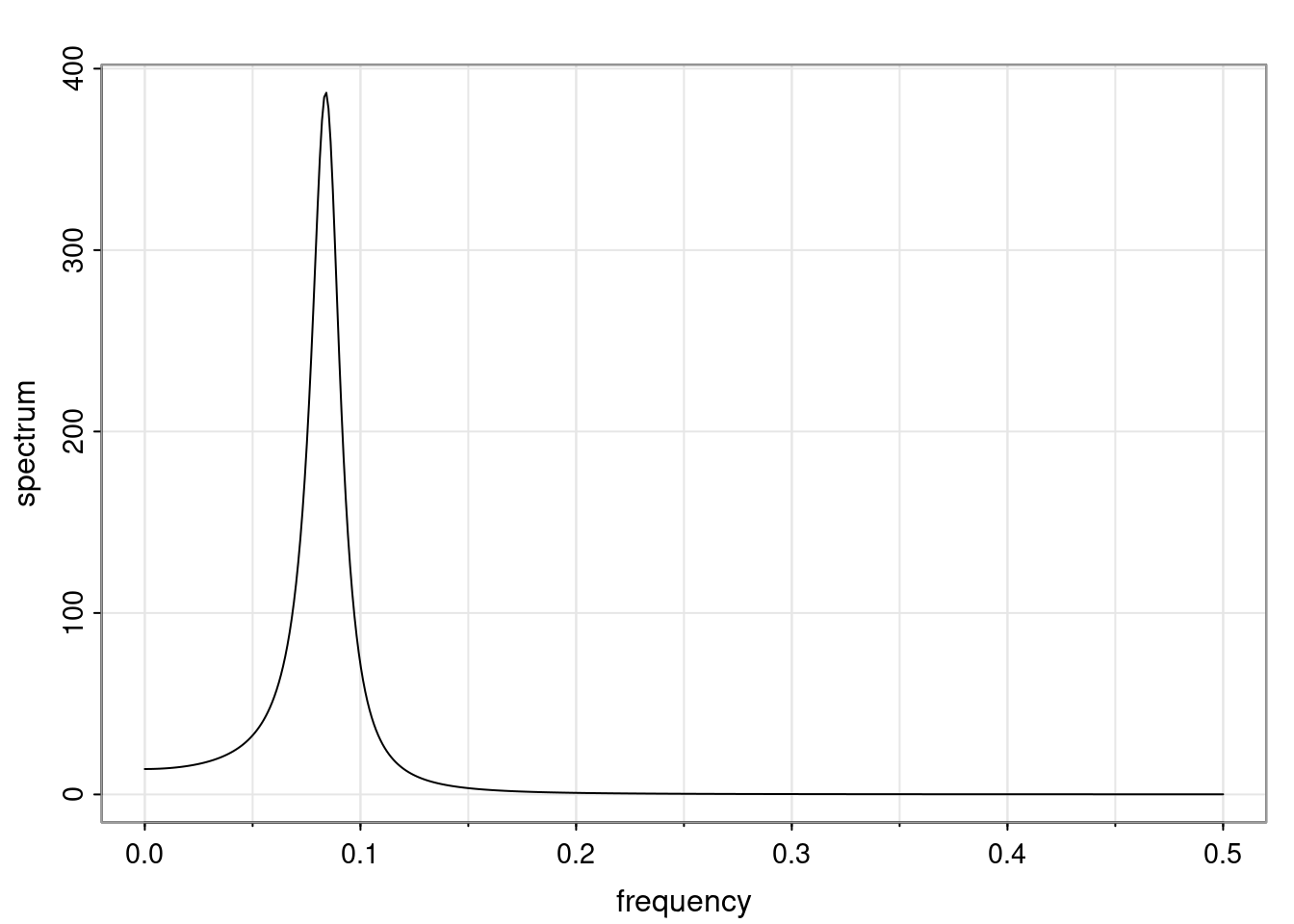

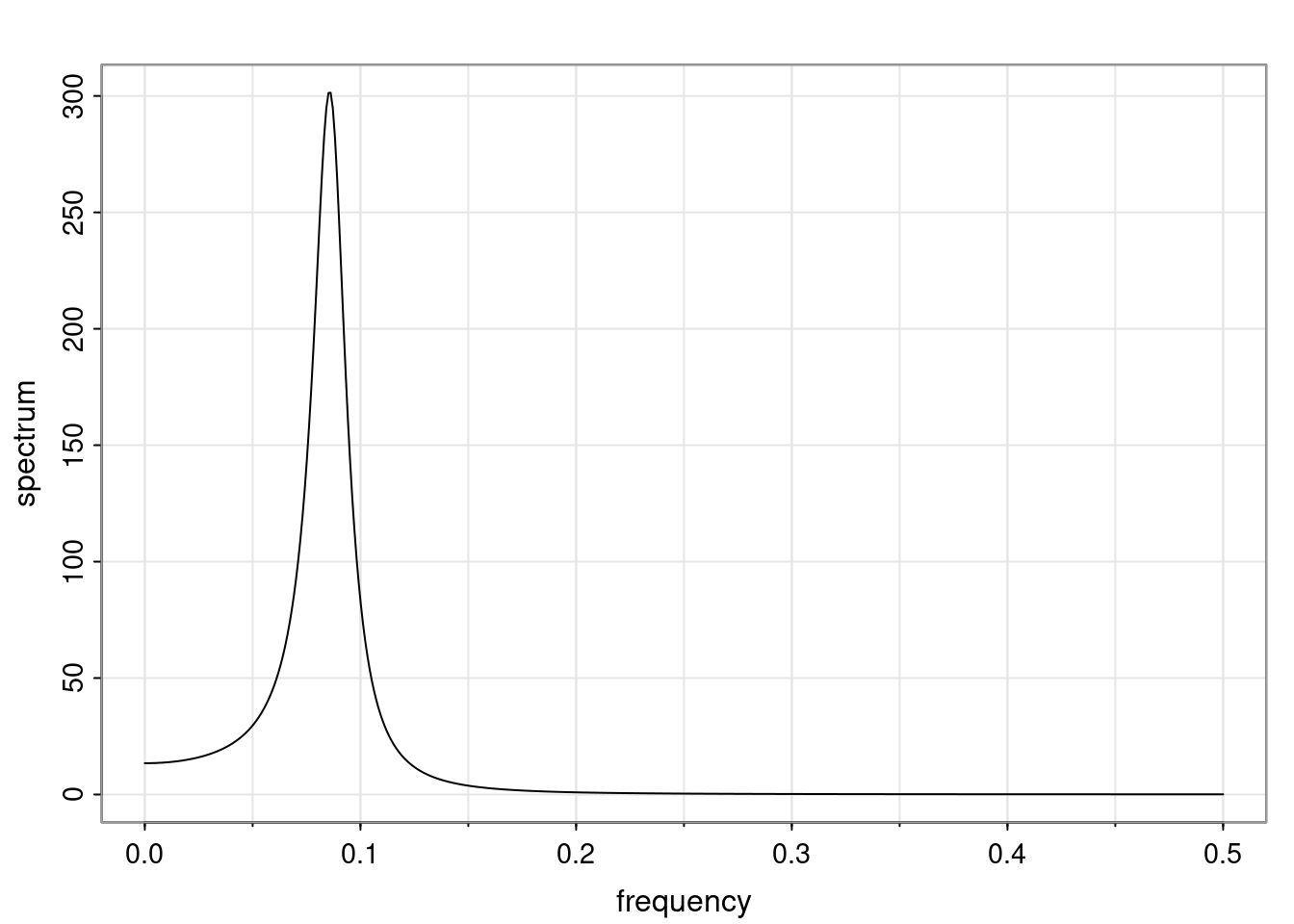

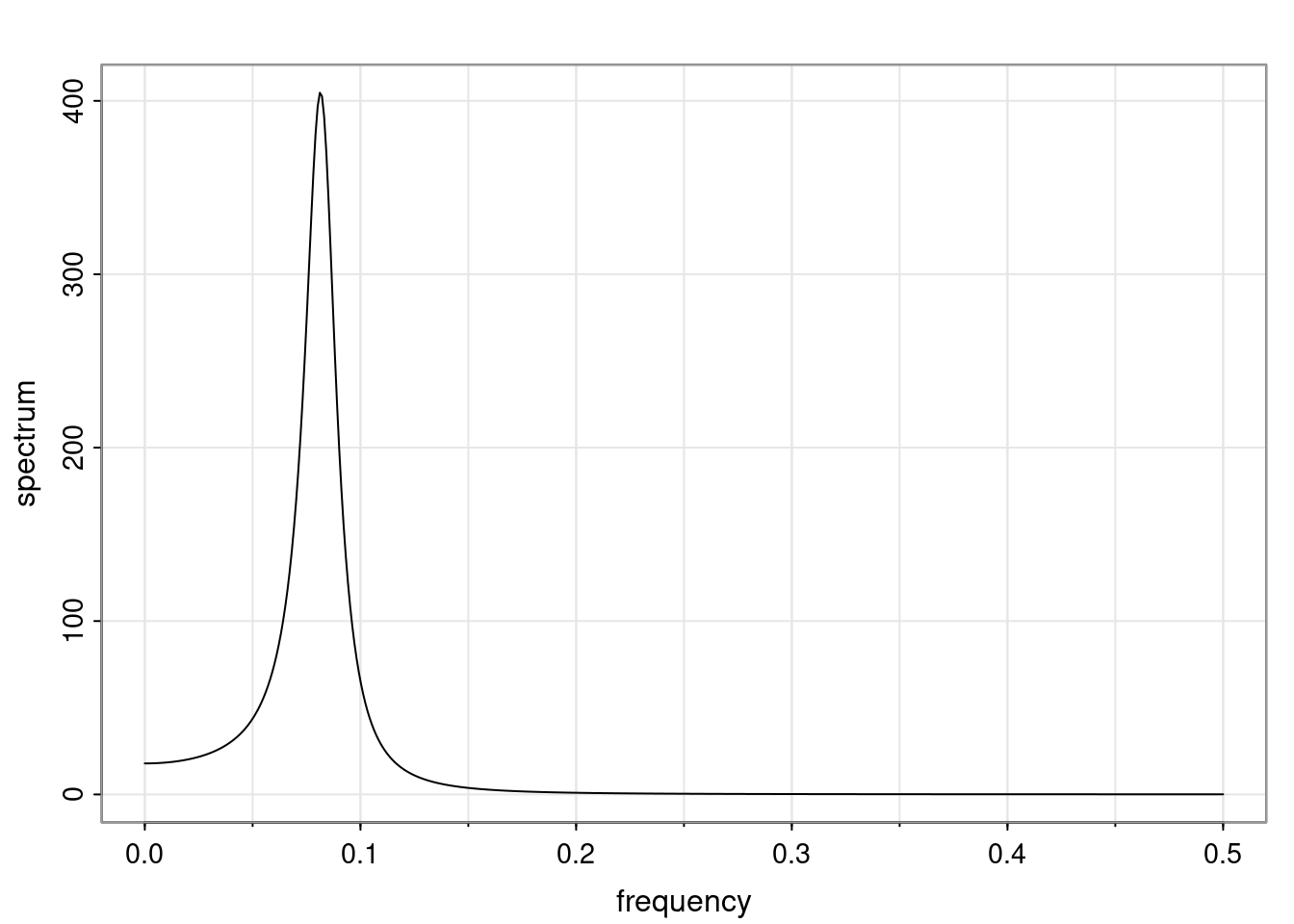

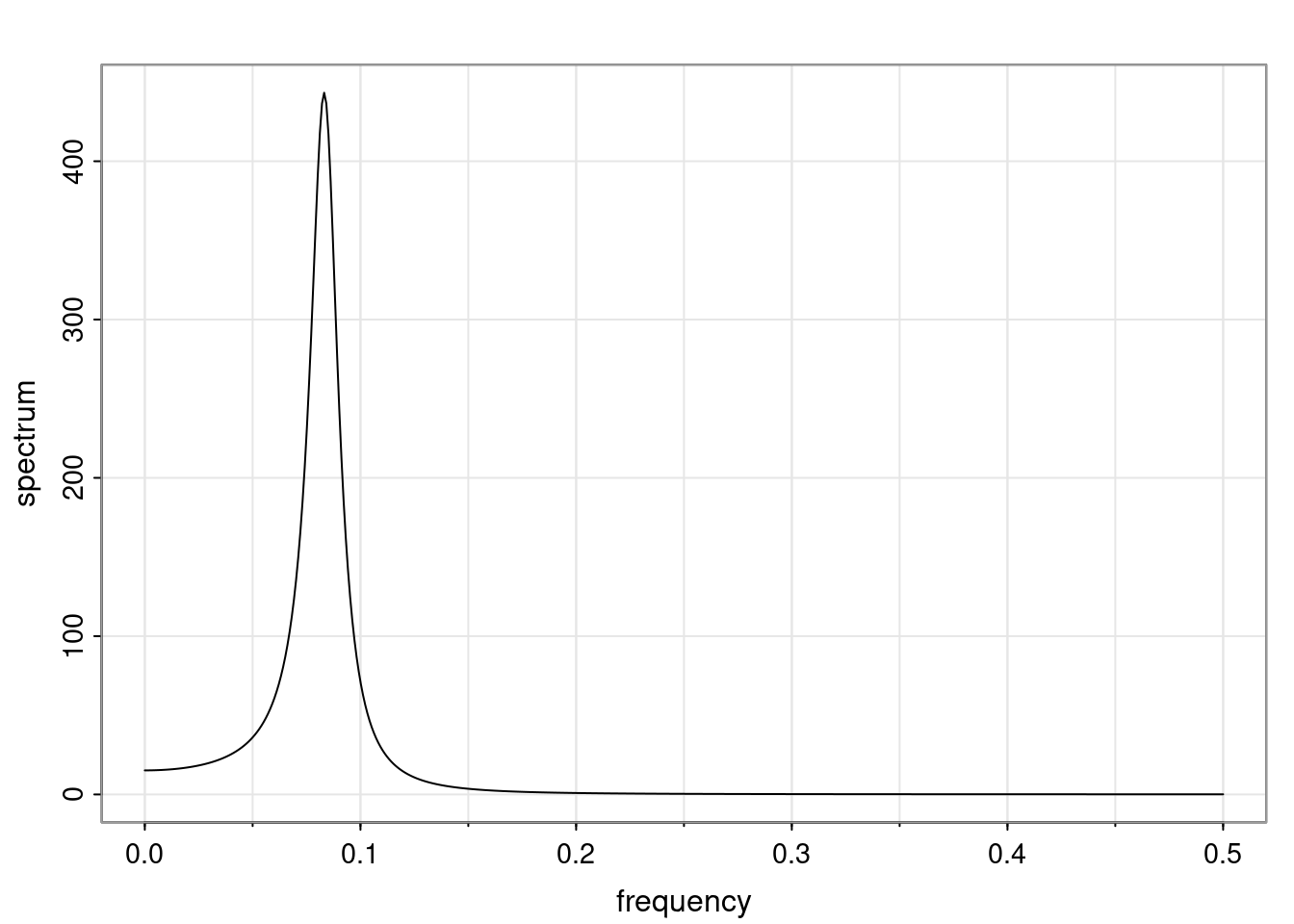

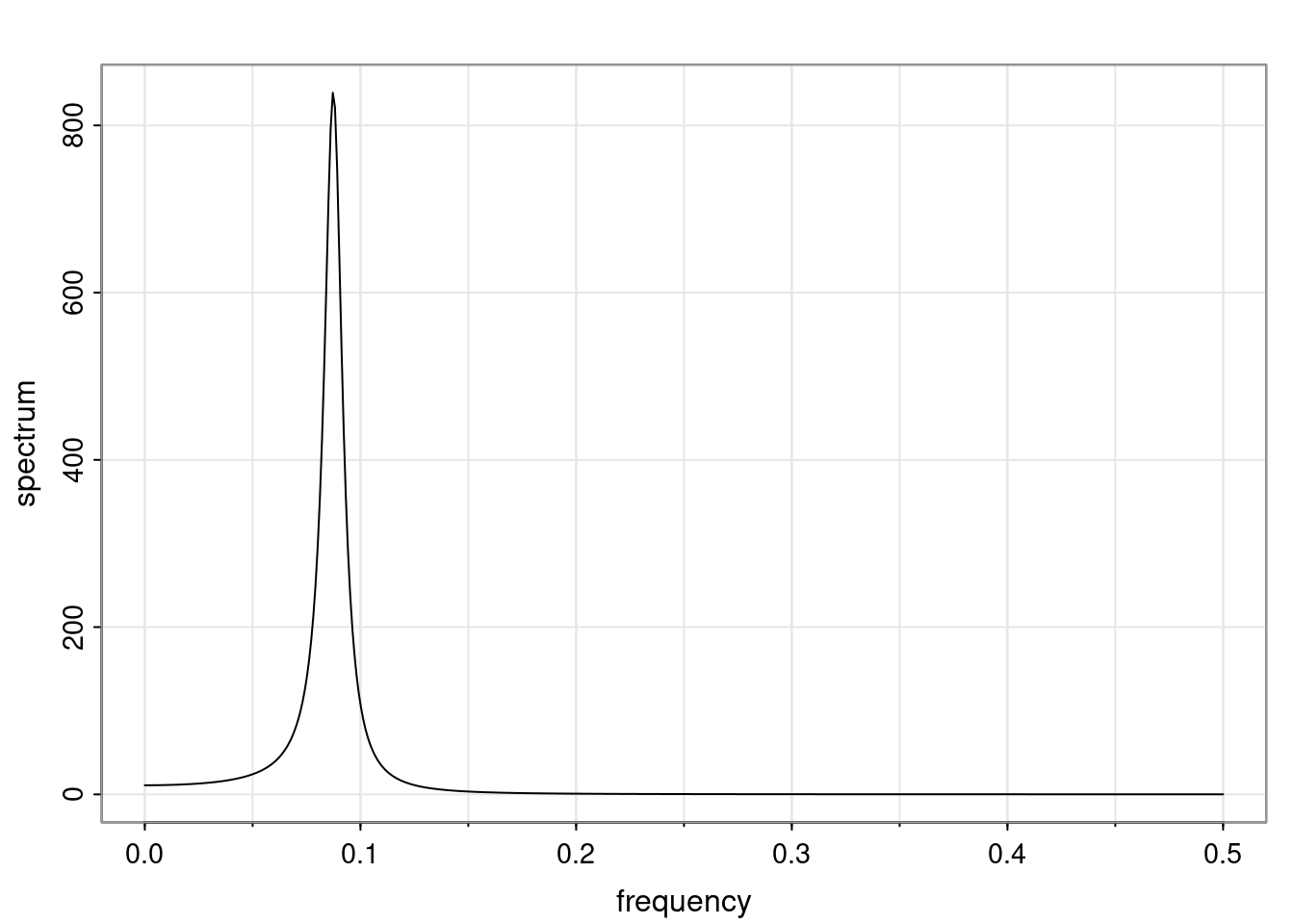

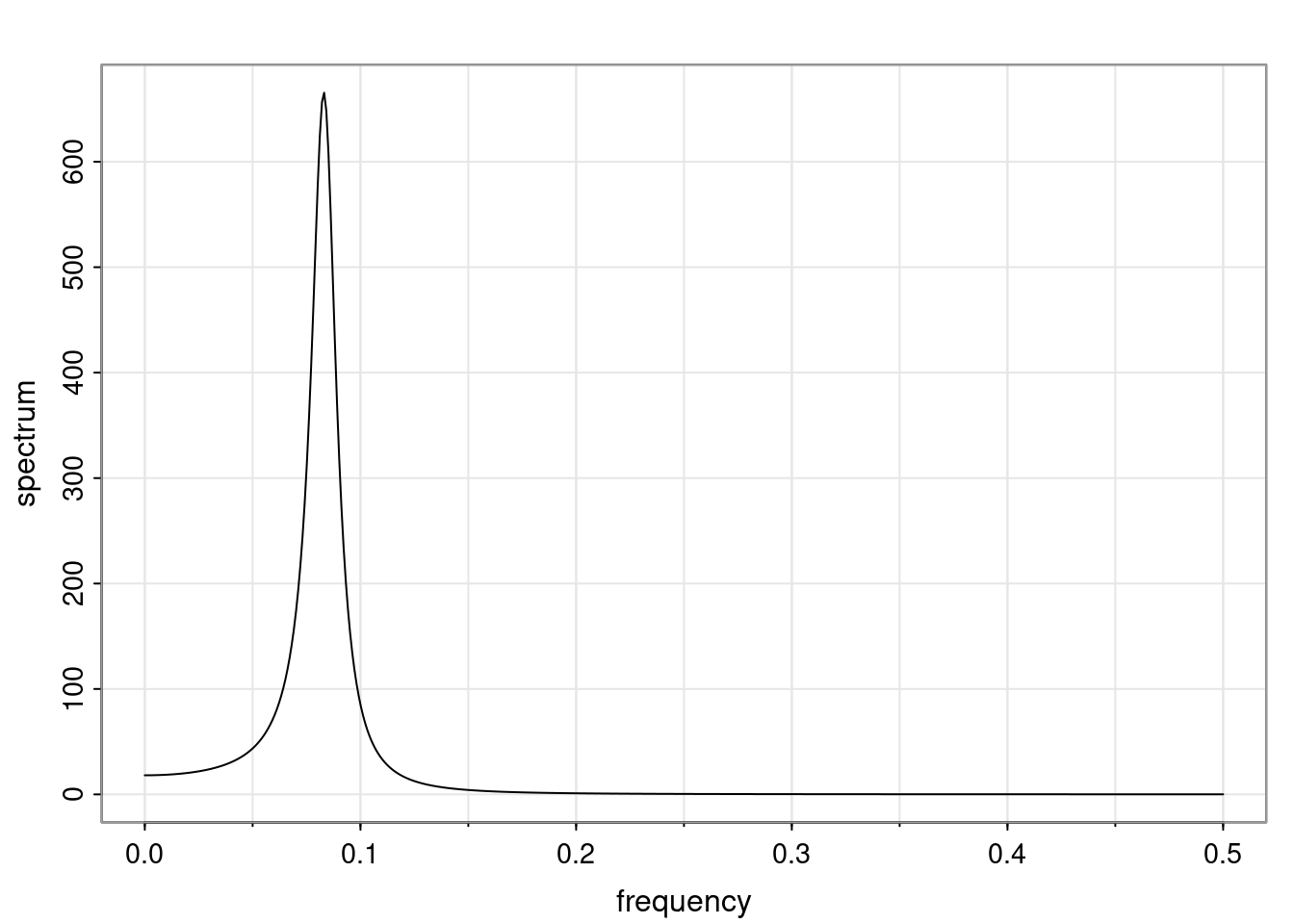

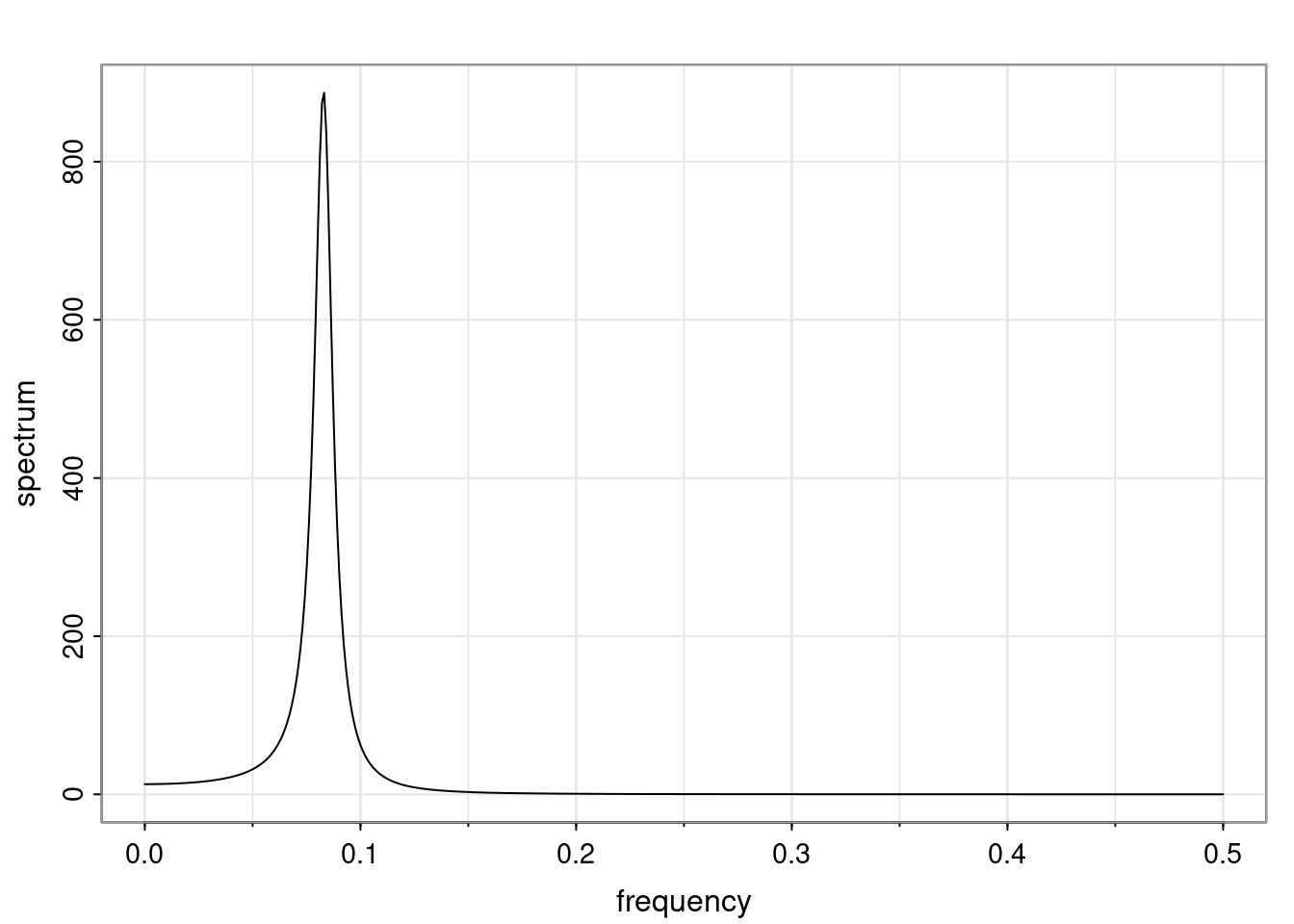

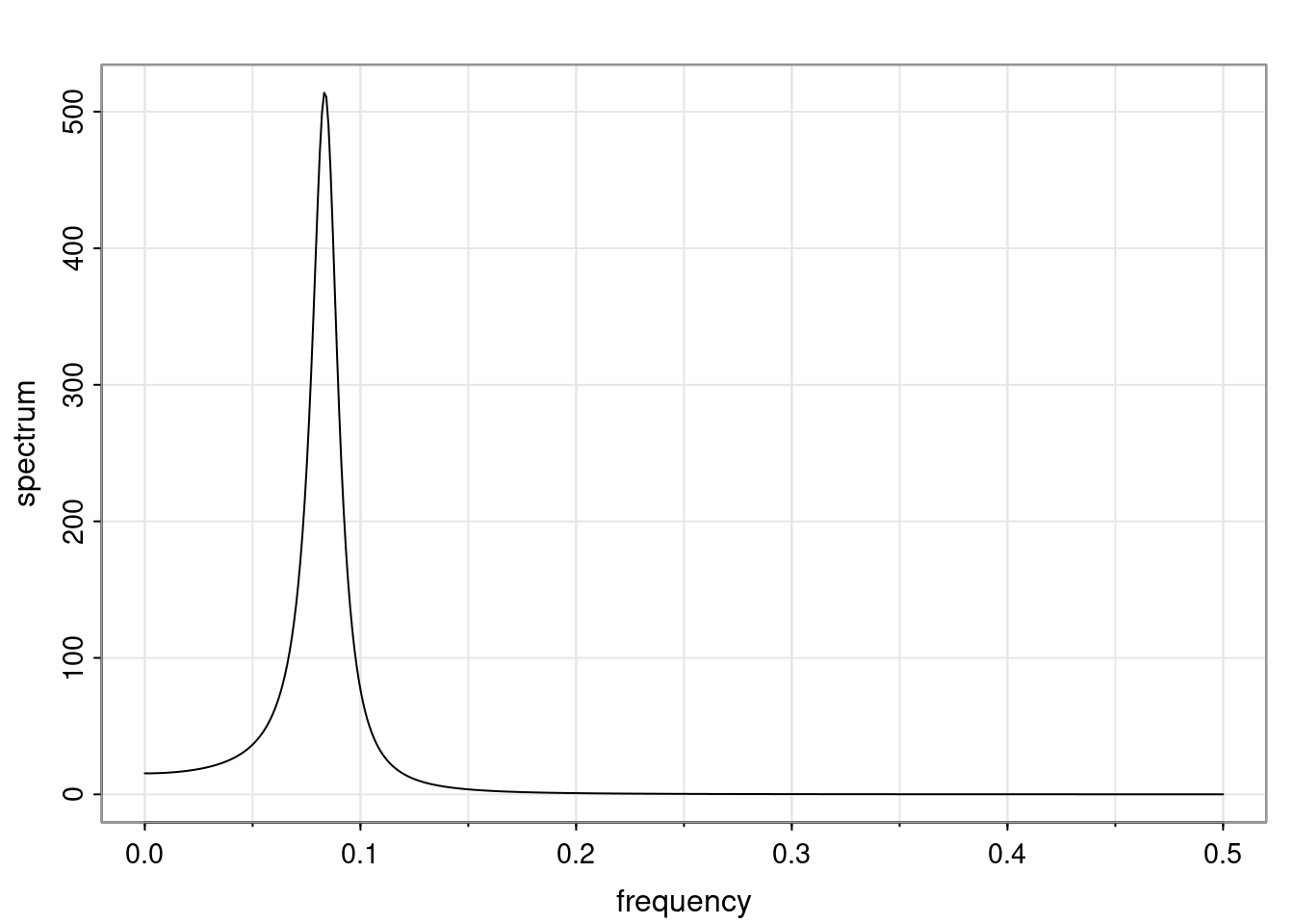

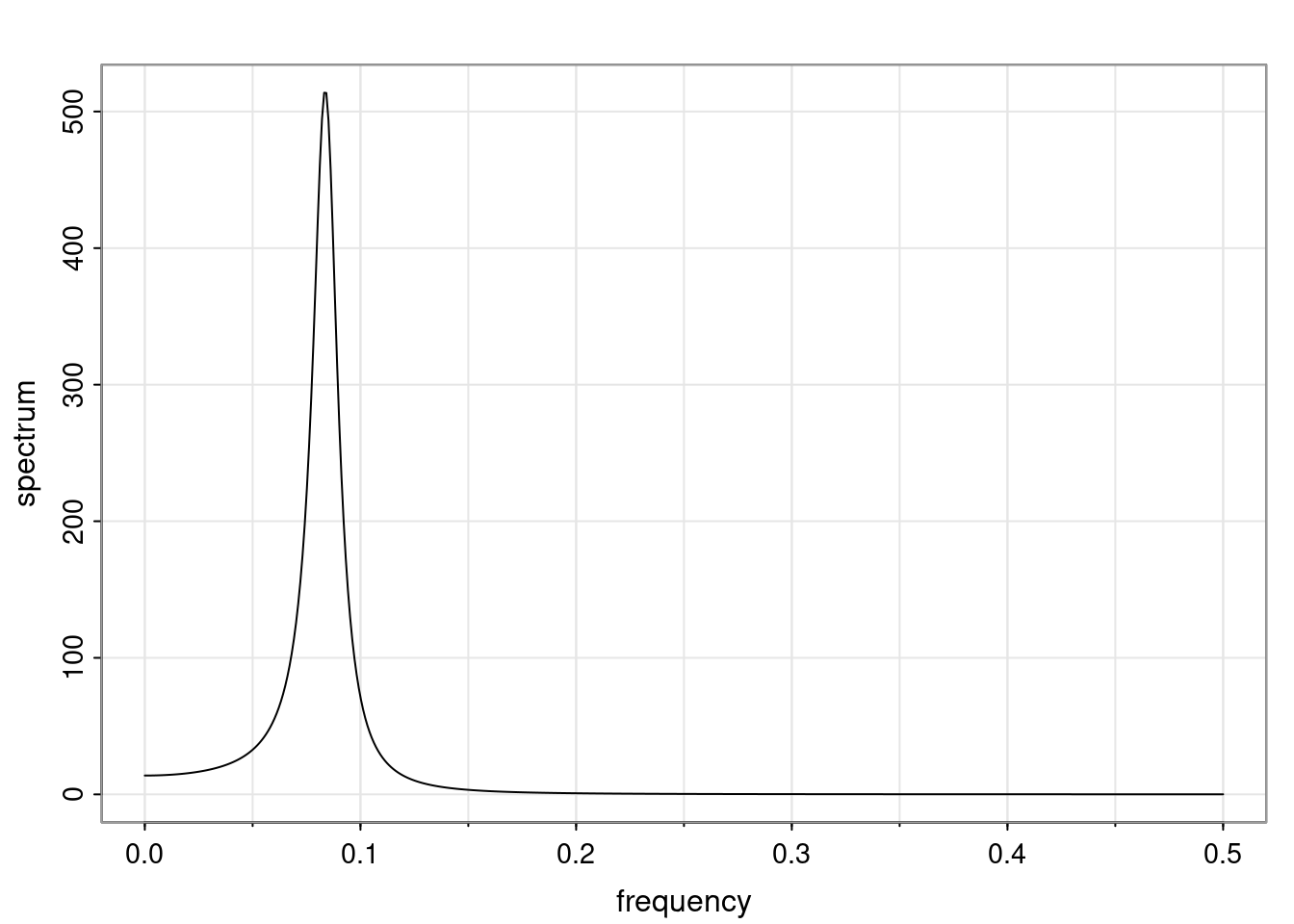

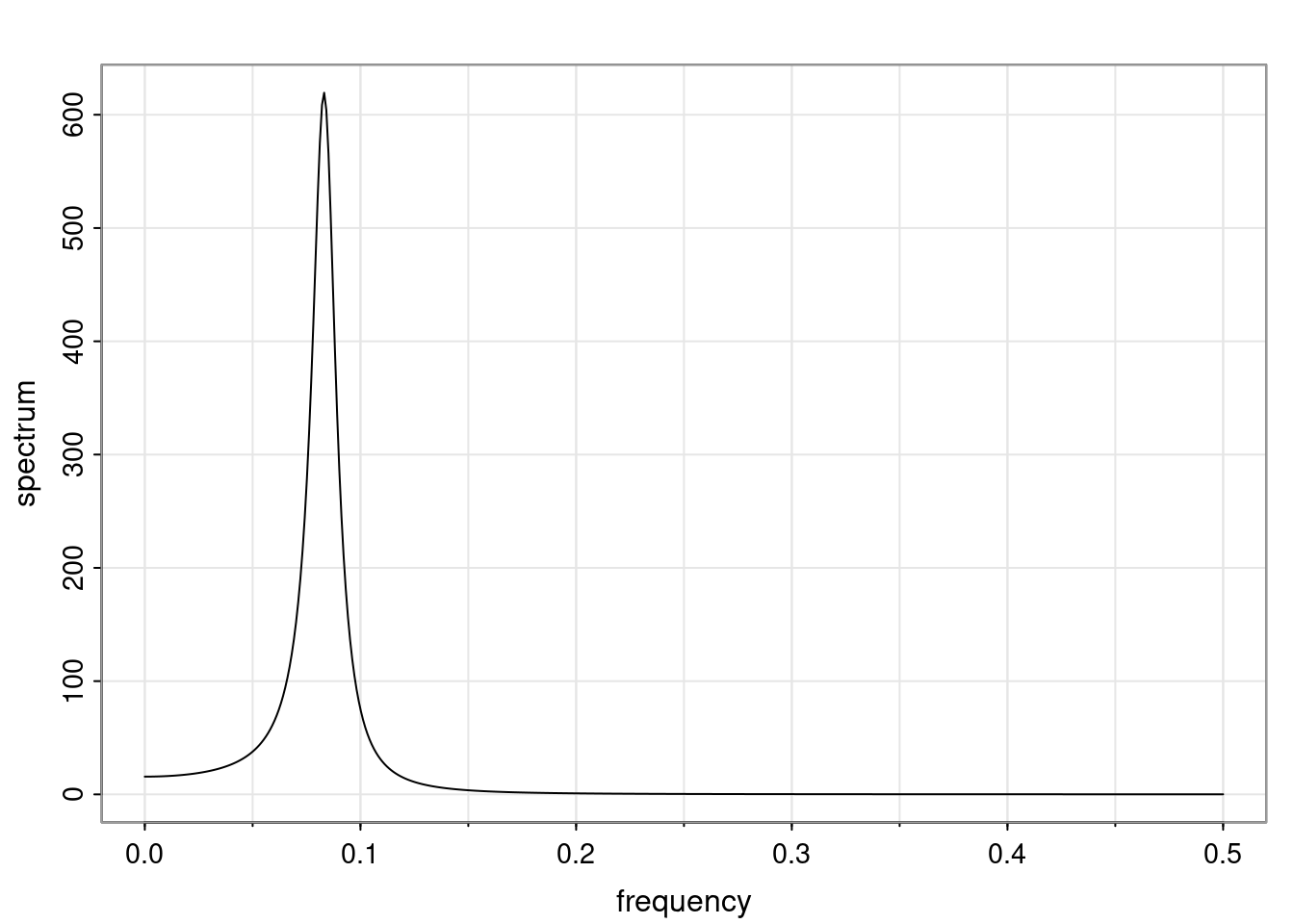

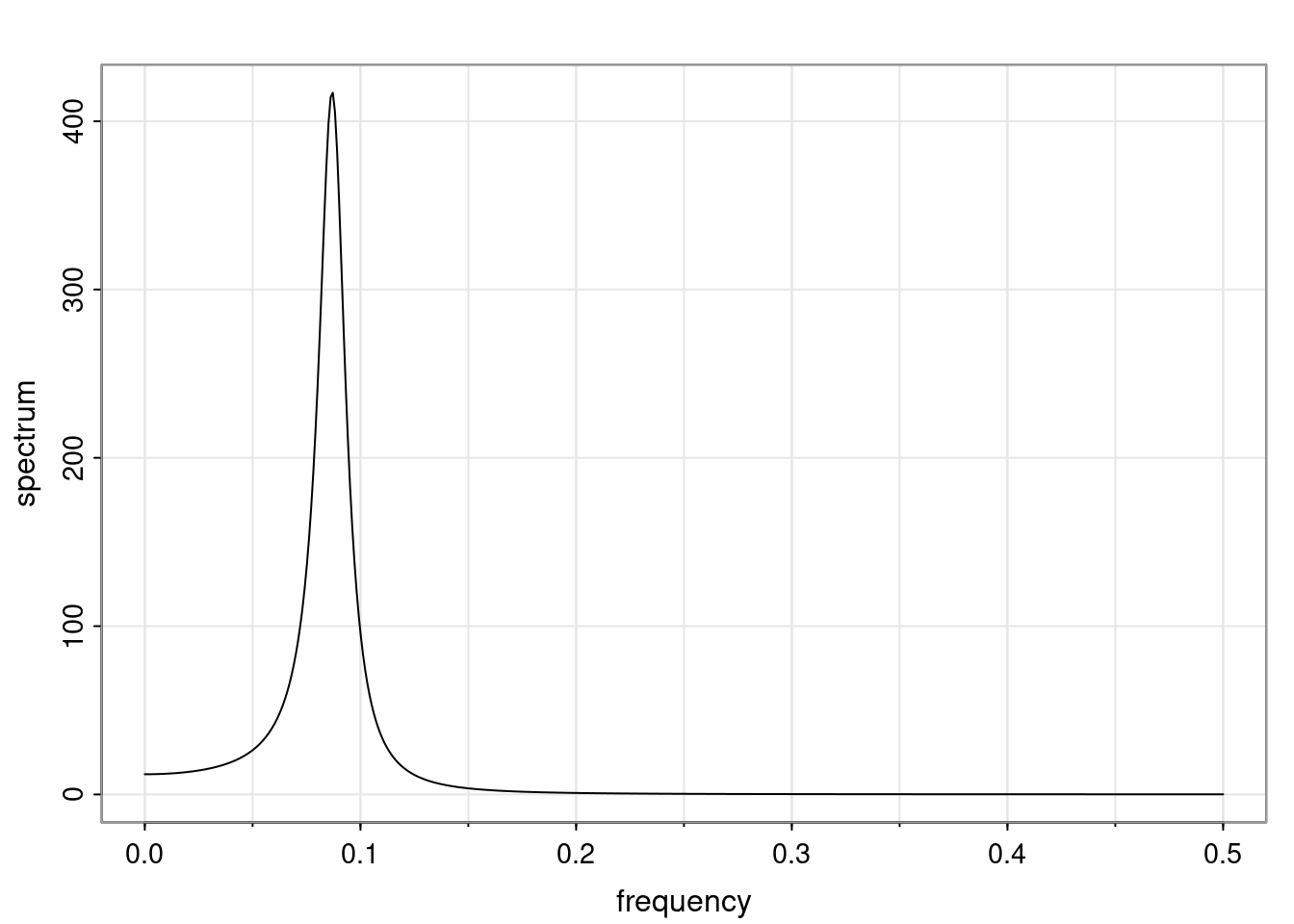

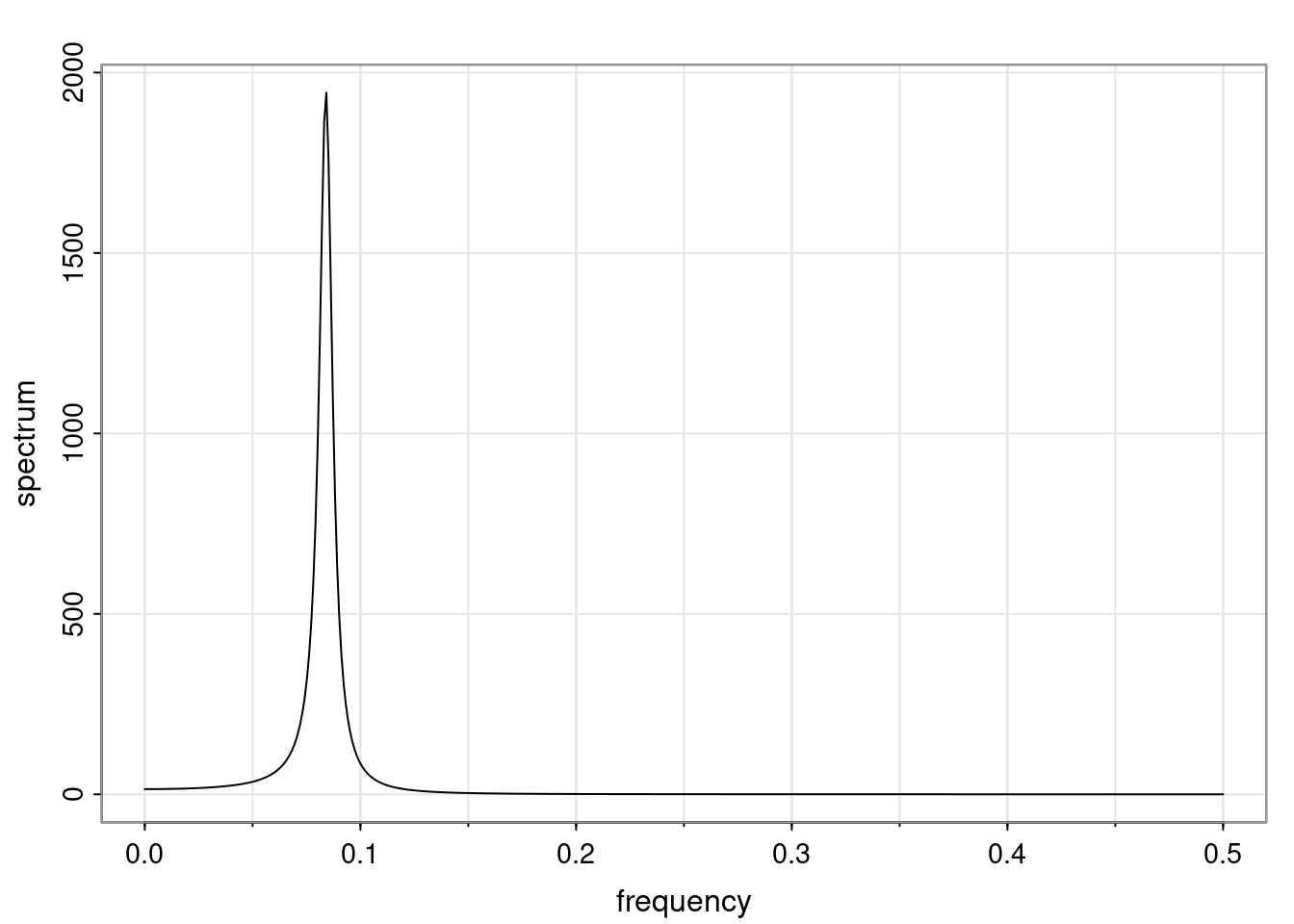

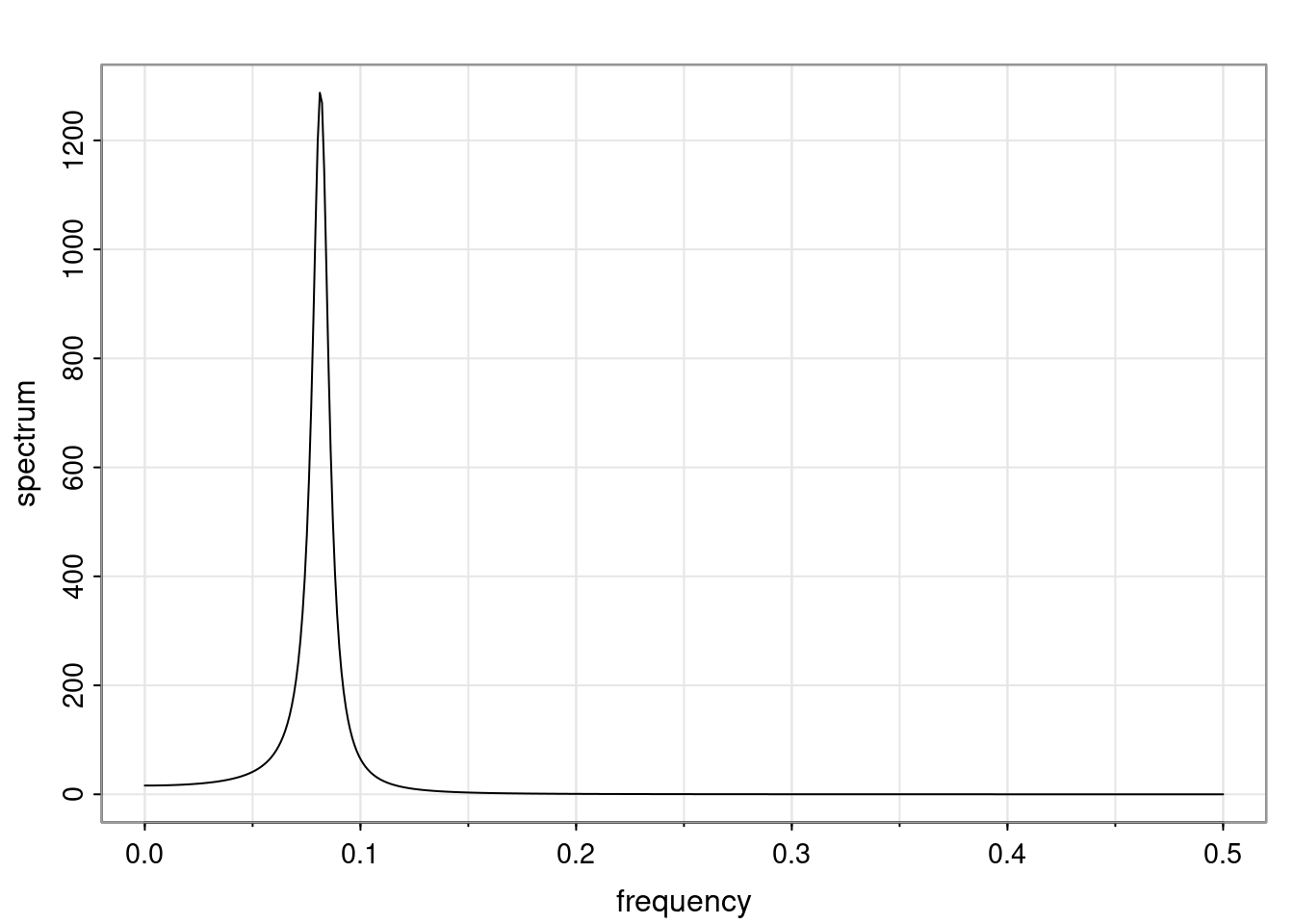

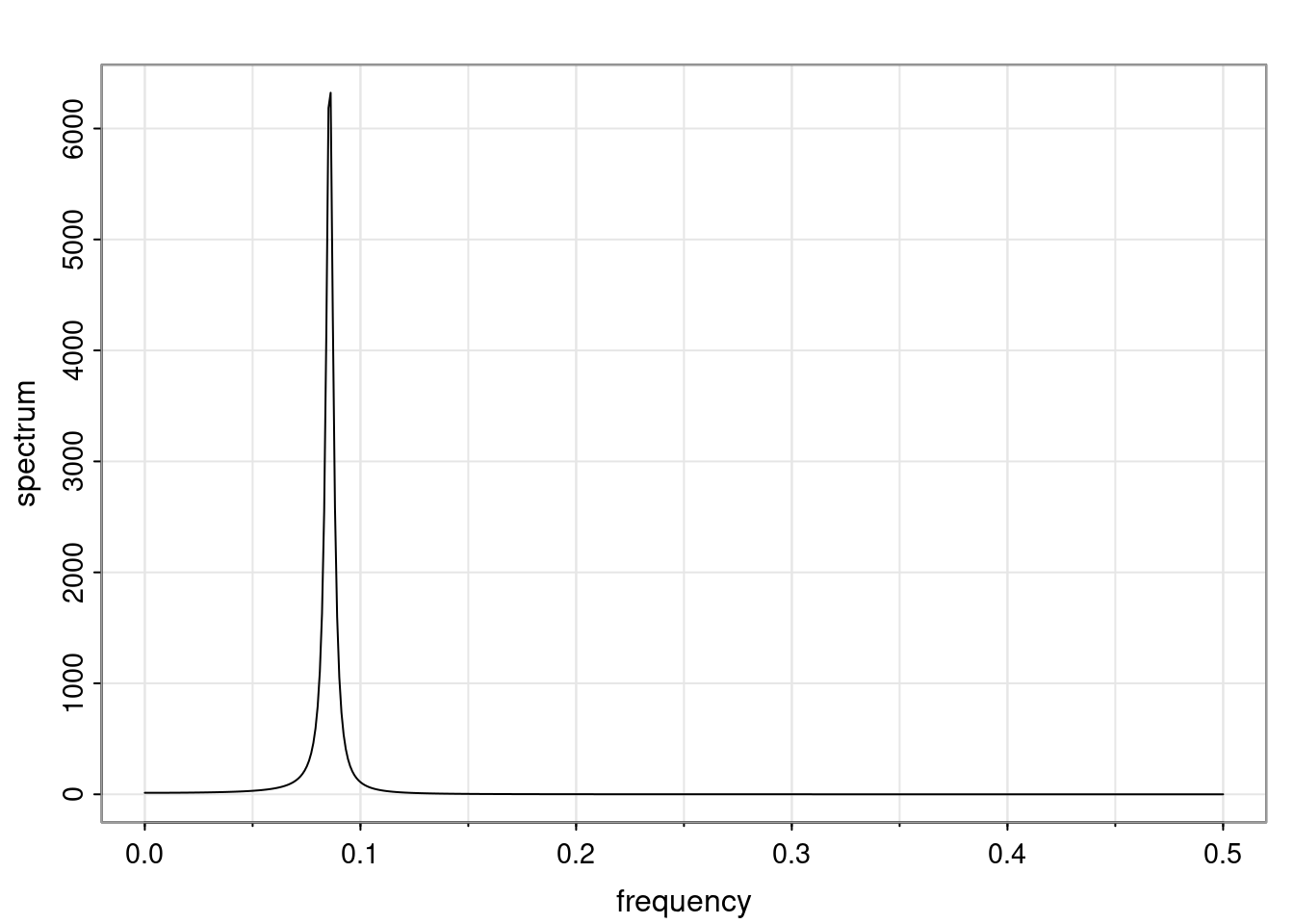

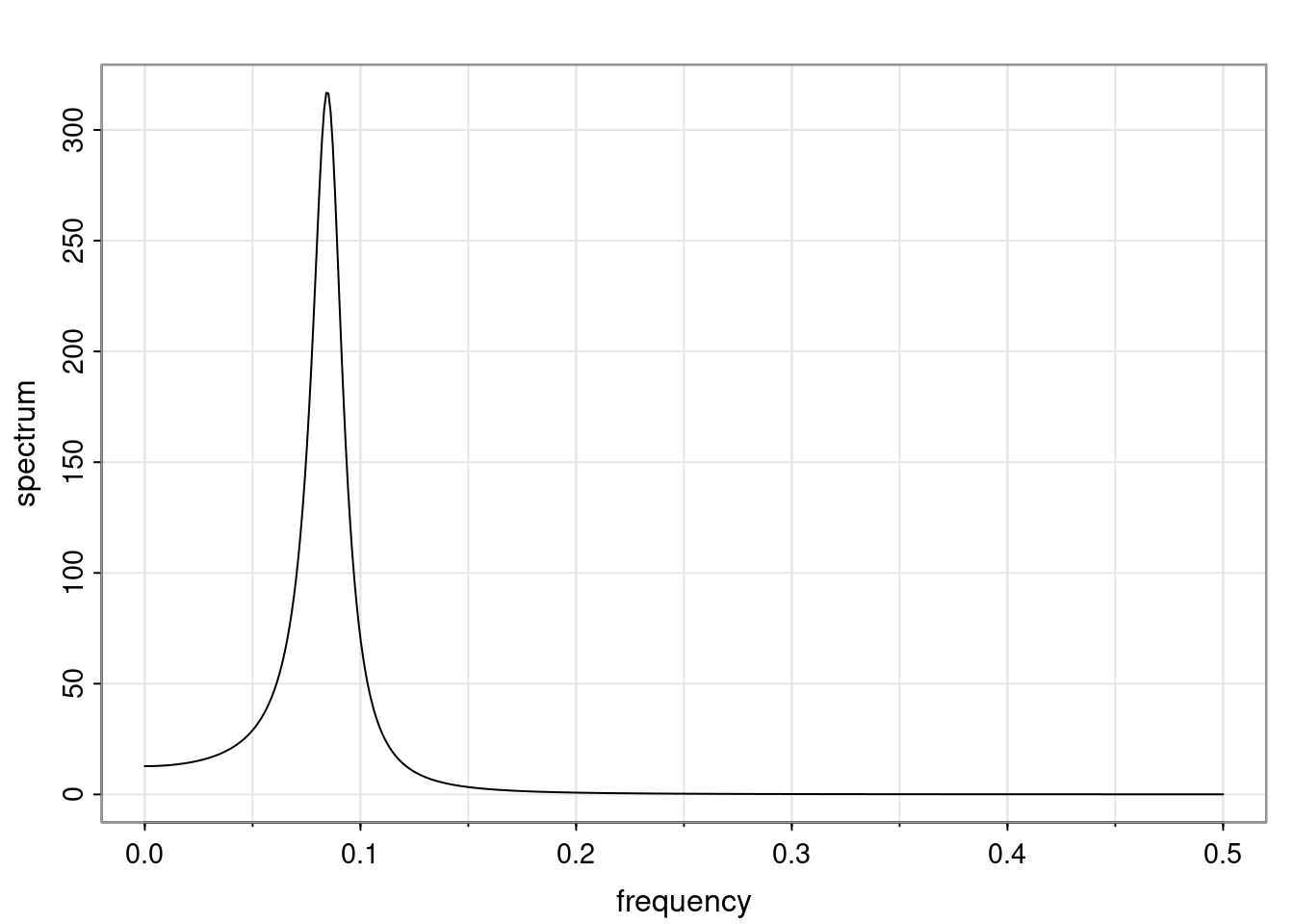

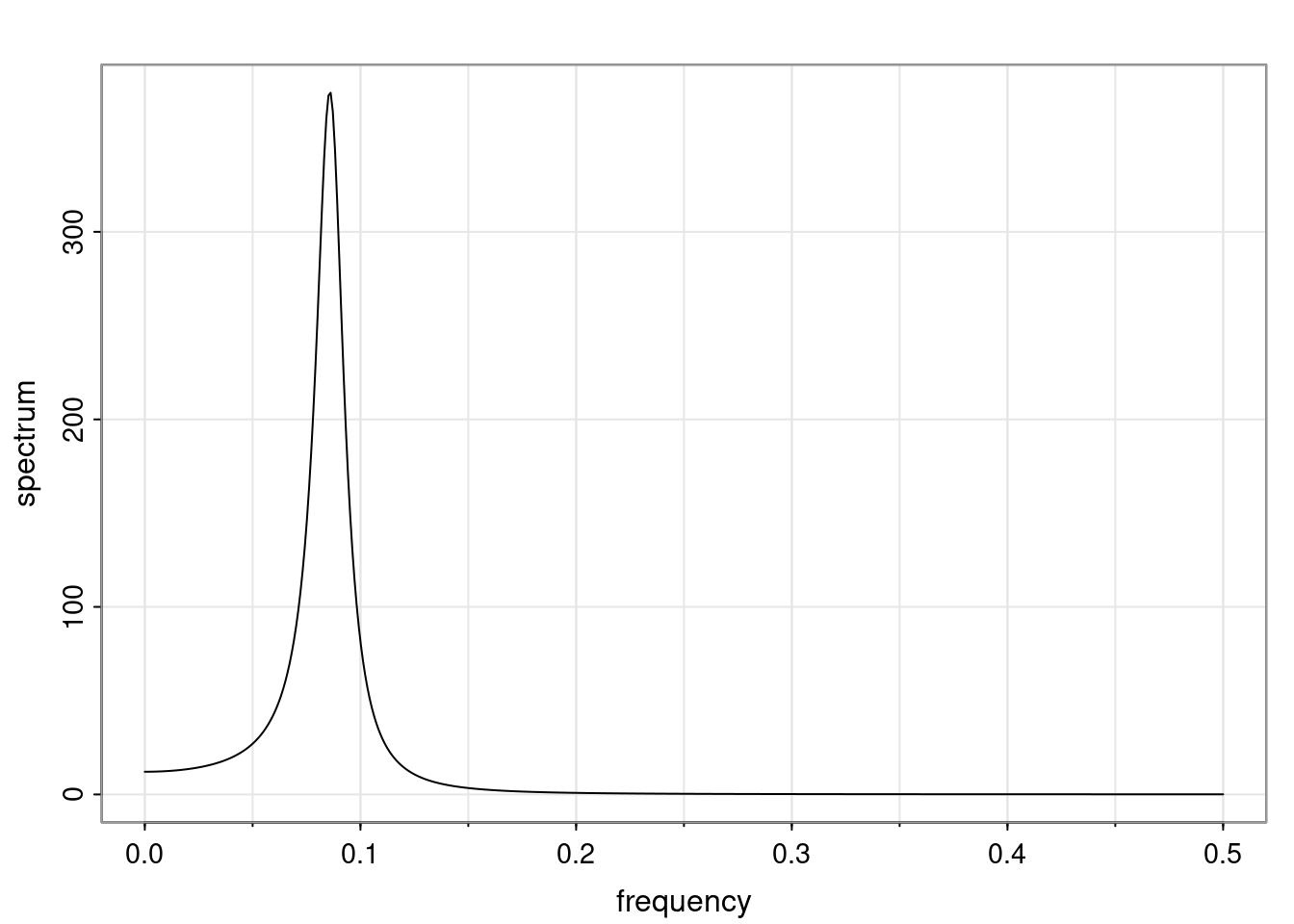

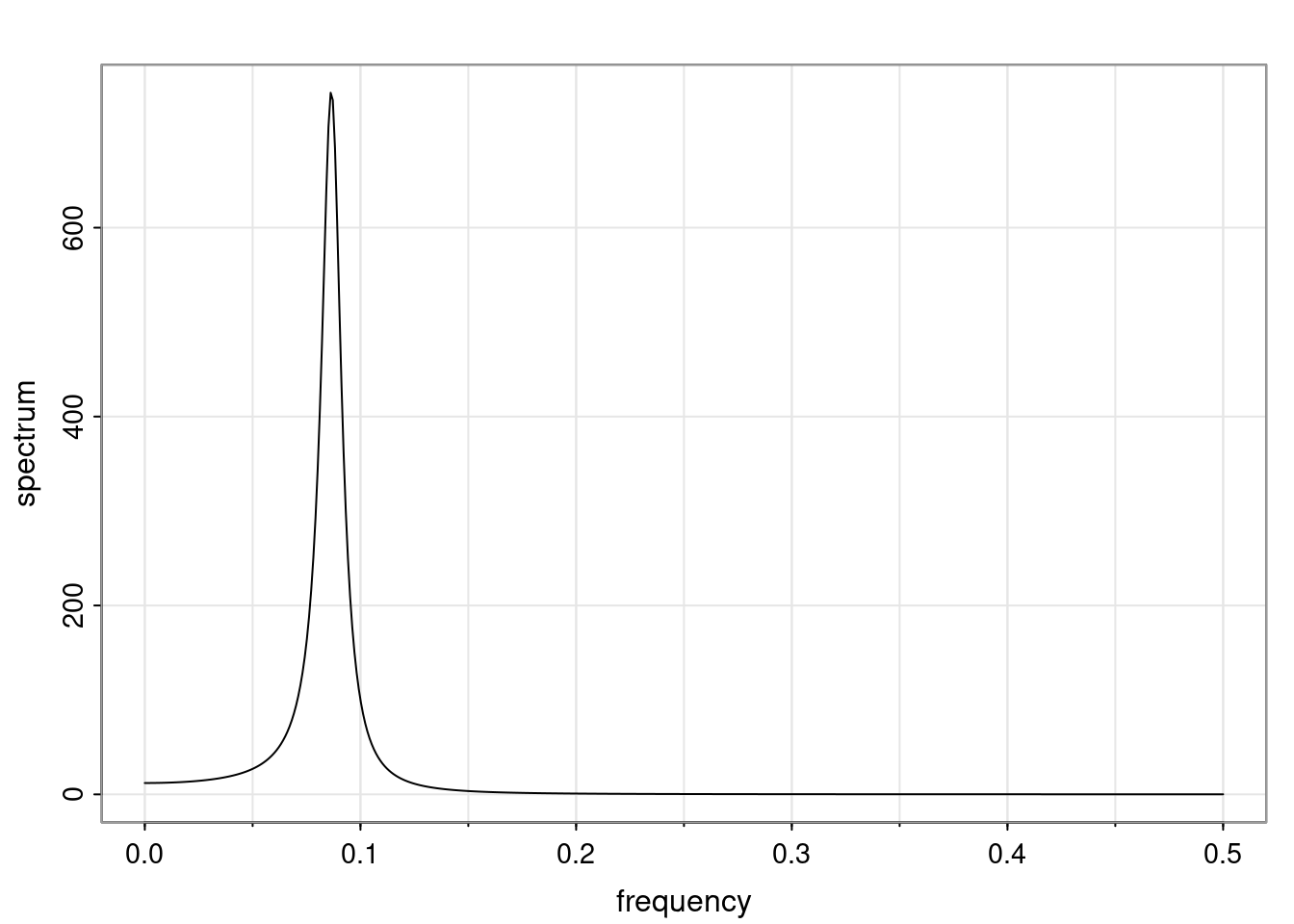

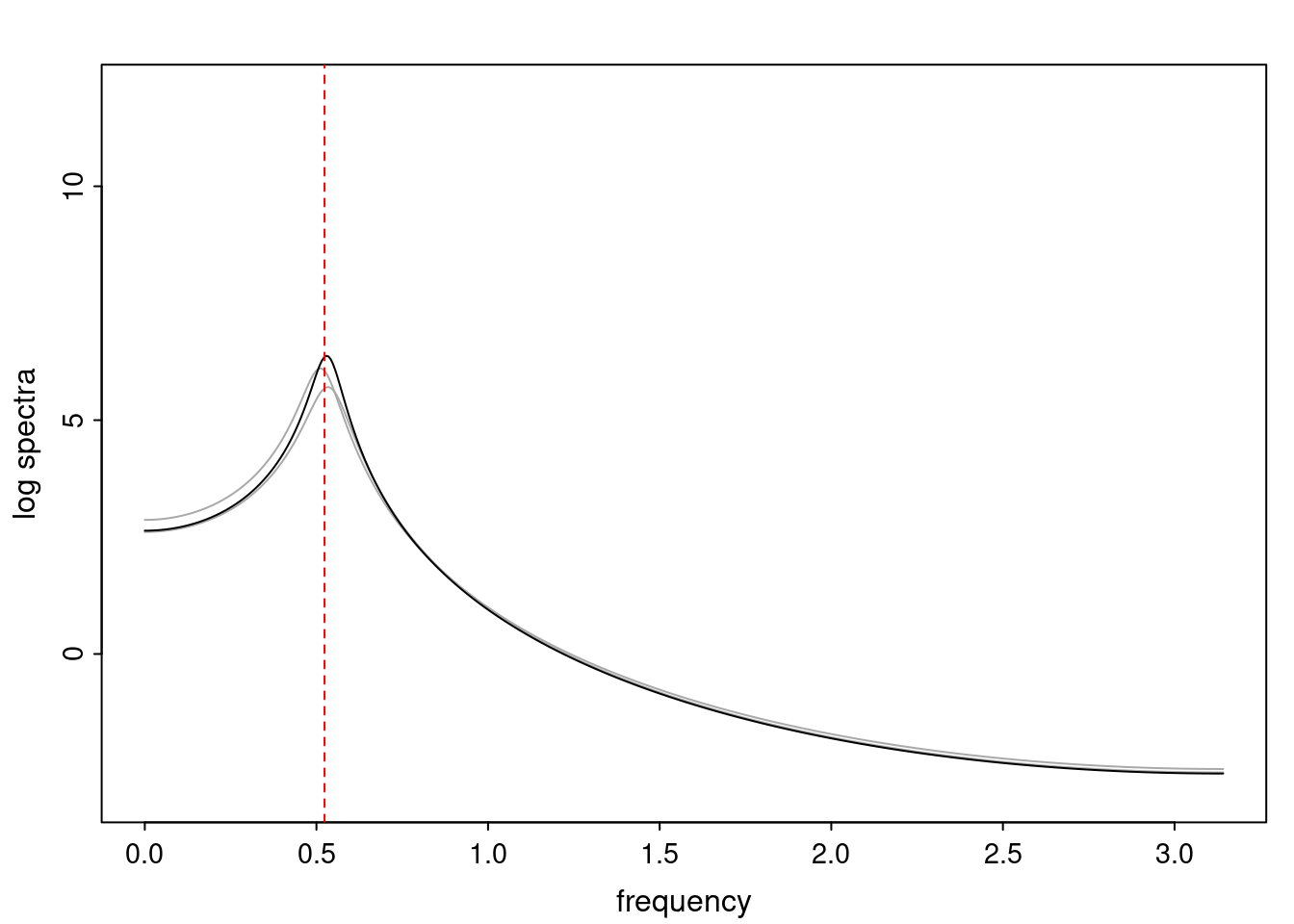

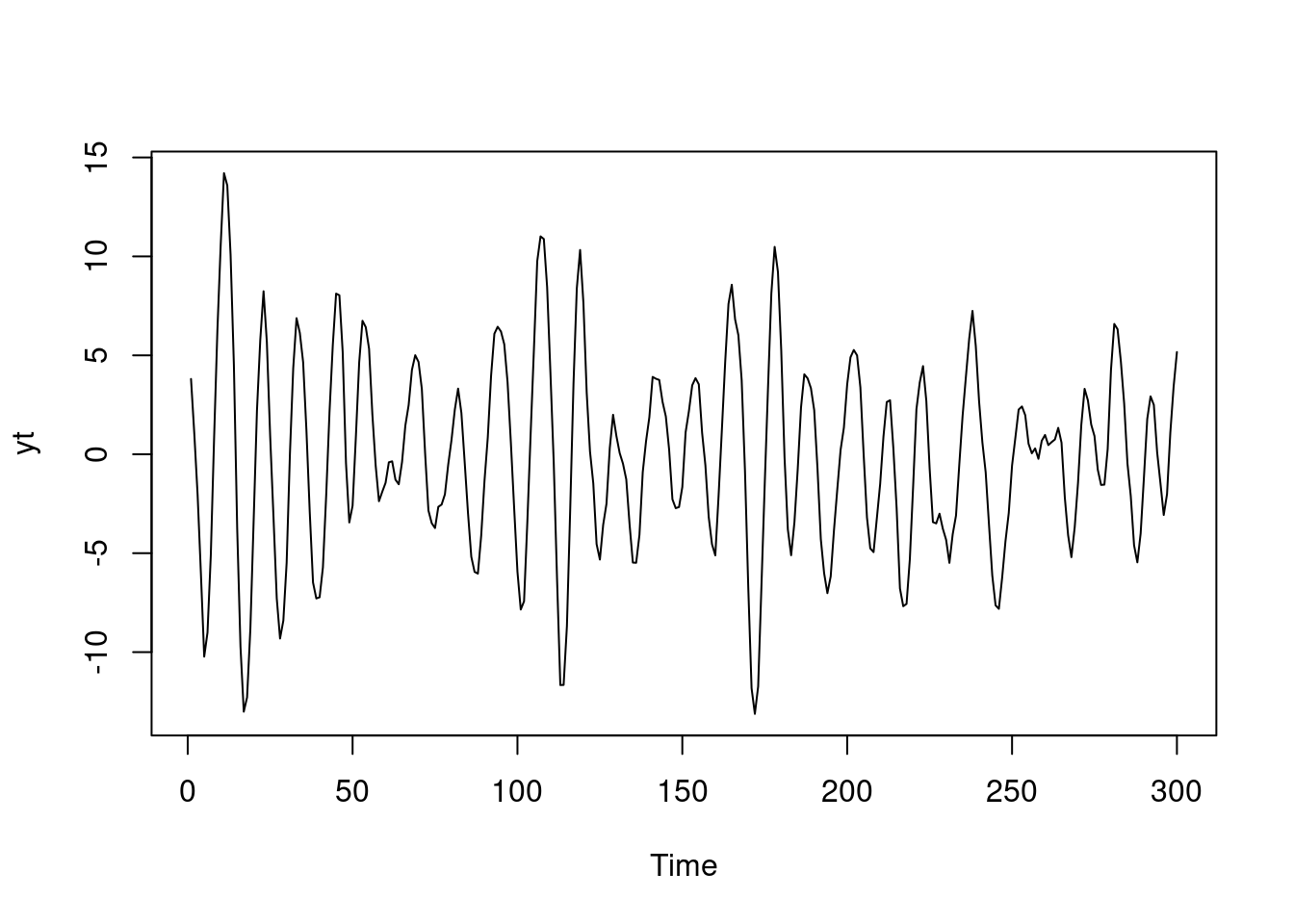

Again, why do we care? Well, if you look at what we have here, we have the power G to the power of h. Using that eigendecomposition, we can get to write this in this form. Whatever elements you have in the matrix of eigenvectors, they are now going to be functions of the reciprocal roots. The power that appears here, which is the number of steps ahead that you want to forecast in your time series for prediction, I’m just going to have the Alphas to the power of h. When I do this calculation, I can end up writing the forecast function just by doing that calculation as a sum from j equals 1 up to p of some constants. Those constants are going to be related to those E matrices but the important point is that what appears here is my Alpha to the power of h. What this means is I’m breaking this expected value of what I’m going to see in the future in terms of a function of the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial. You can see that if the process is stable, is going to be stationary, all the moduli of my reciprocal roots are going to be below one. This is going to decay exponentially as a function of h. You’re going to have something that decays exponentially. Depending on whether those reciprocal roots are real-valued or complex-valued, you’re going to have behavior here that may be quasiperiodic for complex-valued roots or just non-quasiperiodic for the real valued roots. The other thing that matters is, if you’re working with a stable process, are going to have moduli smaller than one. The contribution of each of the roots to these forecasts function is going to be dependent on how close that modulus of that reciprocal root is to one or minus one. For roots that have relatively large values of the modulus, then they are going to have more contribution in terms of what’s going to happen in the future. This provides a way to interpret the AR process.

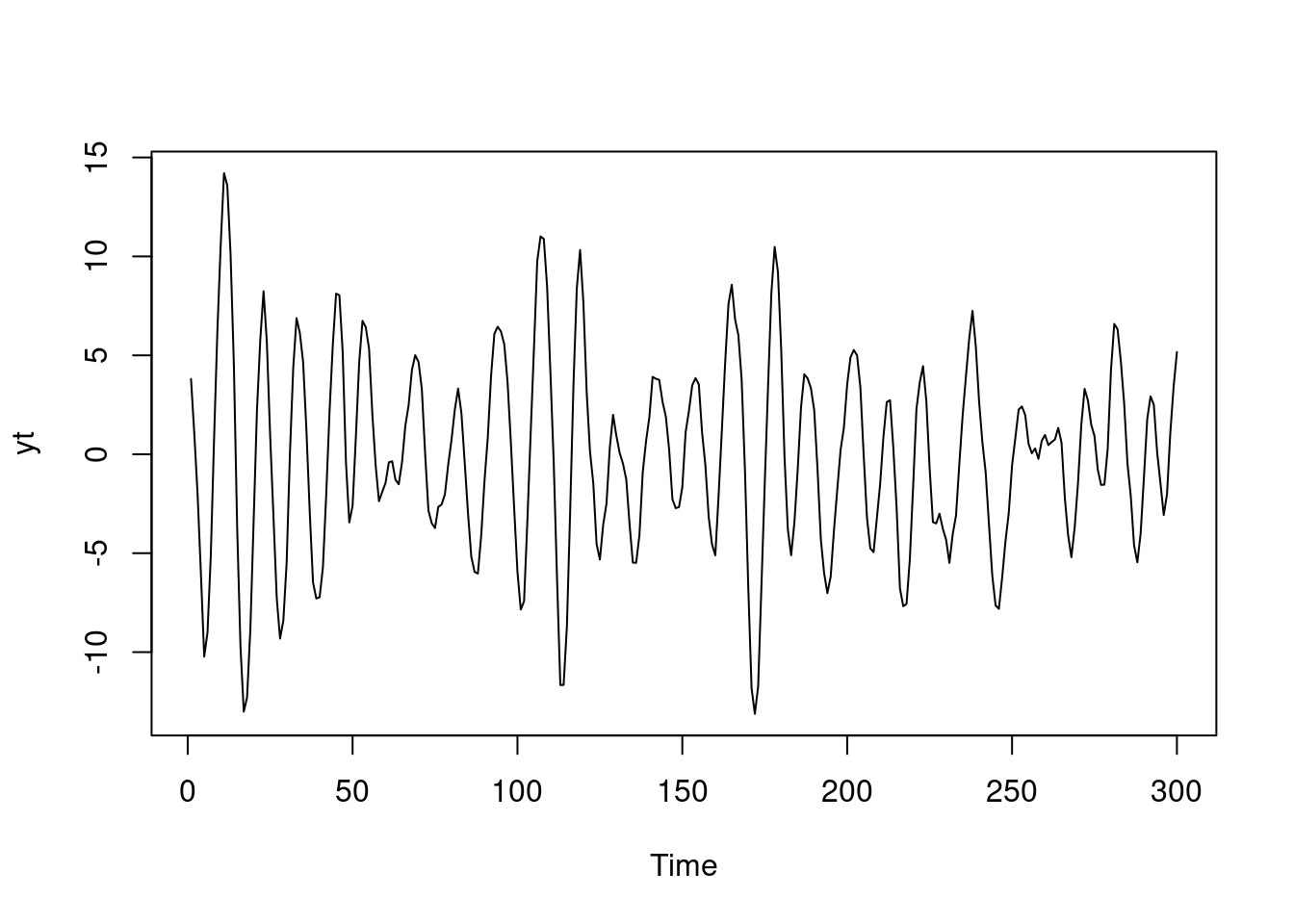

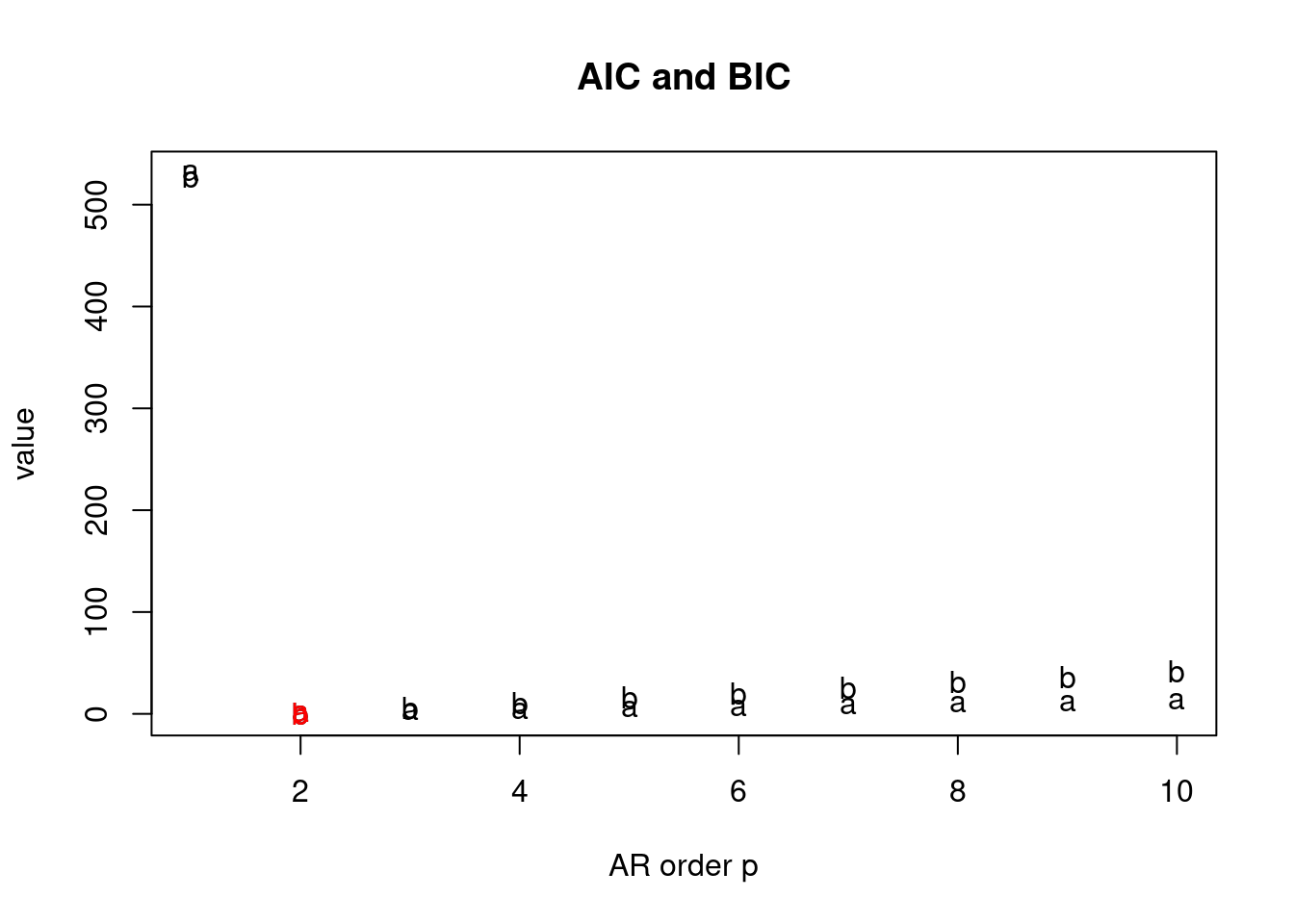

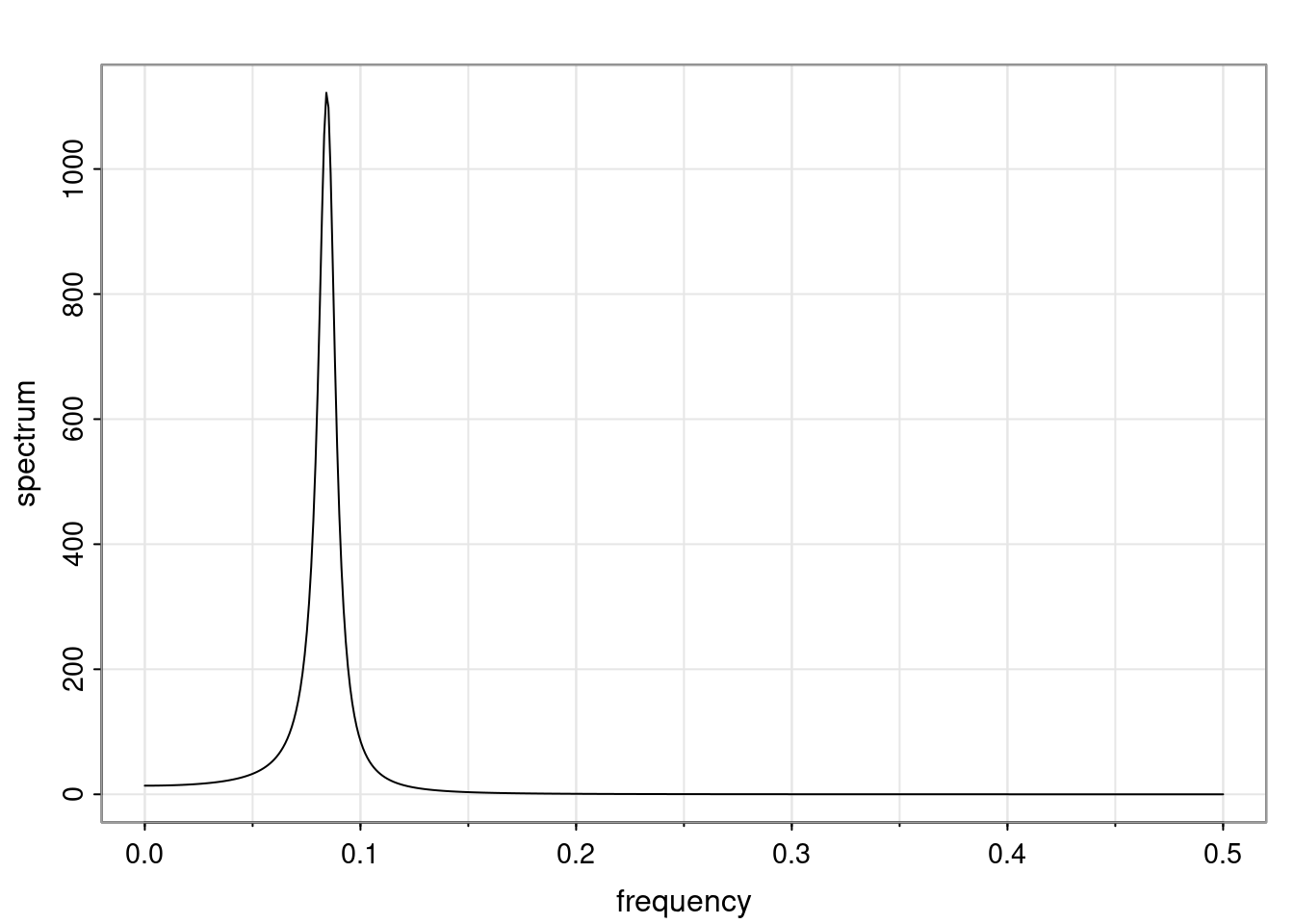

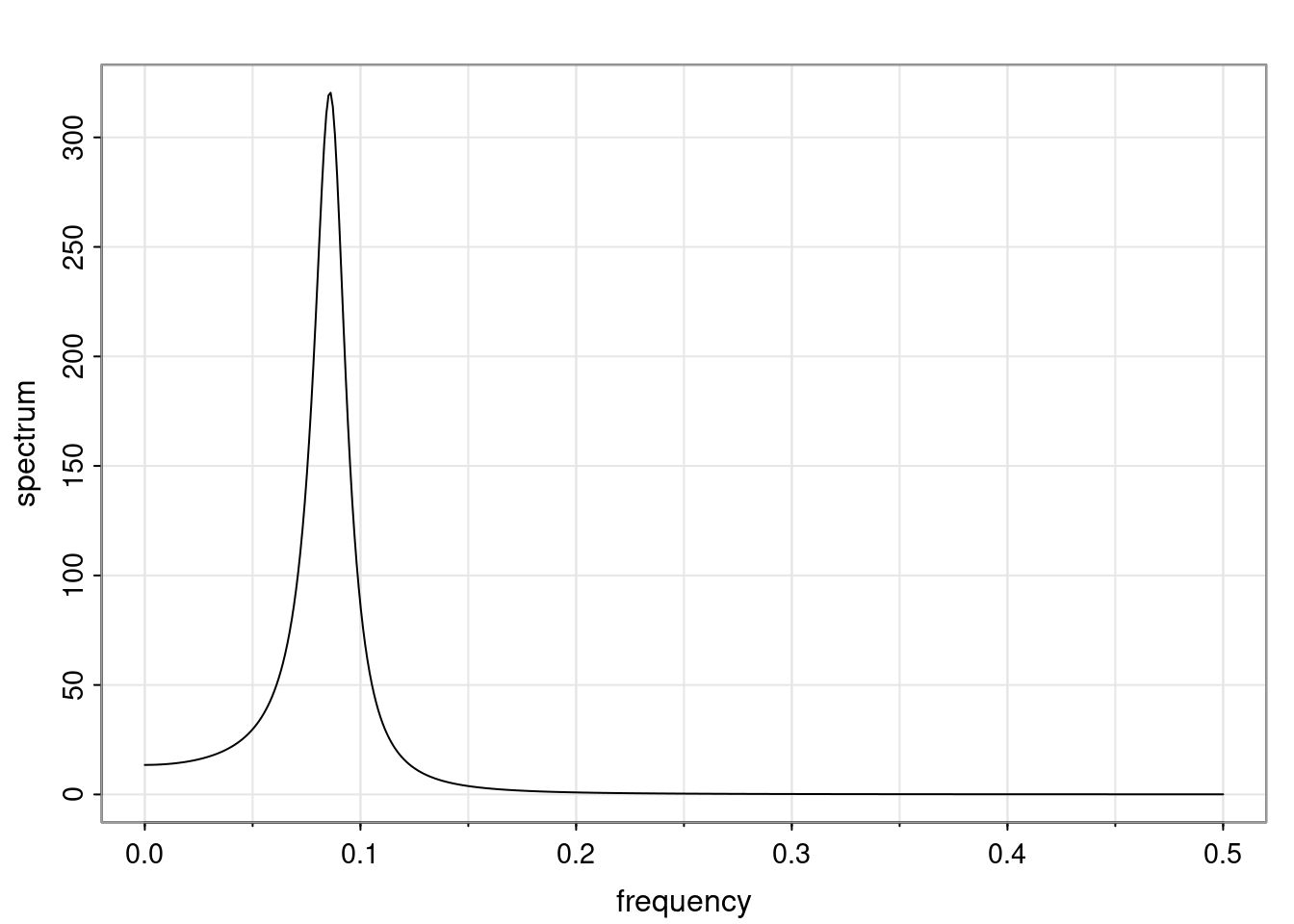

Examples (video)

Nulla eget cursus ipsum. Vivamus porttitor leo diam, sed volutpat lectus facilisis sit amet. Maecenas et pulvinar metus. Ut at dignissim tellus. In in tincidunt elit. Etiam vulputate lobortis arcu, vel faucibus leo lobortis ac. Aliquam erat volutpat. In interdum orci ac est euismod euismod. Nunc eleifend tristique risus, at lacinia odio commodo in. Sed aliquet ligula odio, sed tempor neque ultricies sit amet.

Etiam quis tortor luctus, pellentesque ante a, finibus dolor. Phasellus in nibh et magna pulvinar malesuada. Ut nisl ex, sagittis at sollicitudin et, sollicitudin id nunc. In id porta urna. Proin porta dolor dolor, vel dapibus nisi lacinia in. Pellentesque ante mauris, ornare non euismod a, fermentum ut sapien. Proin sed vehicula enim. Aliquam tortor odio, vestibulum vitae odio in, tempor molestie justo. Praesent maximus lacus nec leo maximus blandit.

Maecenas turpis velit, ultricies non elementum vel, luctus nec nunc. Nulla a diam interdum, faucibus sapien viverra, finibus metus. Donec non tortor diam. In ut elit aliquet, bibendum sem et, aliquam tortor. Donec congue, sem at rhoncus ultrices, nunc augue cursus erat, quis porttitor mauris libero ut ex. Nullam quis leo urna. Donec faucibus ligula eget pellentesque interdum. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Aenean rhoncus interdum erat ut ultricies. Aenean tempus ex non elit suscipit, quis dignissim enim efficitur. Proin laoreet enim massa, vitae laoreet nulla mollis quis.

ACF of the AR(p) (video)

Nunc ac dignissim magna. Vestibulum vitae egestas elit. Proin feugiat leo quis ante condimentum, eu ornare mauris feugiat. Pellentesque habitant morbi tristique senectus et netus et malesuada fames ac turpis egestas. Mauris cursus laoreet ex, dignissim bibendum est posuere iaculis. Suspendisse et maximus elit. In fringilla gravida ornare. Aenean id lectus pulvinar, sagittis felis nec, rutrum risus. Nam vel neque eu arcu blandit fringilla et in quam. Aliquam luctus est sit amet vestibulum eleifend. Phasellus elementum sagittis molestie. Proin tempor lorem arcu, at condimentum purus volutpat eu. Fusce et pellentesque ligula. Pellentesque id tellus at erat luctus fringilla. Suspendisse potenti.

Etiam maximus accumsan gravida. Maecenas at nunc dignissim, euismod enim ac, bibendum ipsum. Maecenas vehicula velit in nisl aliquet ultricies. Nam eget massa interdum, maximus arcu vel, pretium erat. Maecenas sit amet tempor purus, vitae aliquet nunc. Vivamus cursus urna velit, eleifend dictum magna laoreet ut. Duis eu erat mollis, blandit magna id, tincidunt ipsum. Integer massa nibh, commodo eu ex vel, venenatis efficitur ligula. Integer convallis lacus elit, maximus eleifend lacus ornare ac. Vestibulum scelerisque viverra urna id lacinia. Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia curae; Aenean eget enim at diam bibendum tincidunt eu non purus. Nullam id magna ultrices, sodales metus viverra, tempus turpis.

The AR(p): Review (Reading)

AR(p): Definition, stability, and stationarity

AR(p)

A time series follows a zero-mean autoregressive process of order p, of AR(p), if:

y_t = \phi_1 y_{t-1} + \phi_2 y_{t-2} + \ldots + \phi_p y_{t-p} + \epsilon_t \qquad

\tag{5}

where \phi_1, \ldots, \phi_p are the AR coefficients and \epsilon_t is a white noise process

with \epsilon_t \sim \text{i.i.d. } N(0, v), for all t.

The AR characteristic polynomial is given by

\Phi(u) = 1 - \phi_1 u - \phi_2 u^2 - \ldots - \phi_p u^p,

with u complex-valued.

The AR(p) process is stable if \Phi(u) = 0 only when |u| > 1. In this case, the process is also stationary and can be written as

y_t = \psi(B) \epsilon_t = \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} \psi_j \epsilon_{t-j},

with \psi_0 = 1 and \sum_{j=0}^{\infty} |\psi_j| < \infty. Here B denotes the backshift operator, so B^j \epsilon_t = \epsilon_{t-j} and

\psi(B) = 1 + \psi_1 B + \psi_2 B^2 + \ldots + \psi_j B^j + \ldots

The AR polynomial can also be written as

\Phi(u) = \prod_{j=1}^{p} (1 - \alpha_j u),

with \alpha_j being the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial. For the process to be stable (and consequently stationary), |\alpha_j| < 1 for all j = 1, \ldots, p.

AR(p): State-space representation

An AR(p) can also be represented using the following state-space or dynamic linear (DLM) model representation:

y_t = F' x_t,

x_t = G x_{t-1} + \omega_t,

with x_t = (y_t, y_{t-1}, \dots, y_{t-p+1})', F = (1, 0, \dots, 0)', \omega_t = (\epsilon_t, 0, \dots, 0)', and

G = \begin{pmatrix}

\phi_1 & \phi_2 & \phi_3 & \dots & \phi_{p-1} & \phi_p \\

1 & 0 & 0 & \dots & 0 & 0 \\

0 & 1 & 0 & \dots & 0 & 0 \\

\vdots & \ddots & \ddots & \ddots & & \vdots \\

0 & 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 & 0

\end{pmatrix}.

Using this representation, the expected behavior of the process in the future can be exhibited via the forecast function:

f_t(h) = E(y_{t+h} | y_{1:t}) = F' G^h x_t, \quad h > 0,

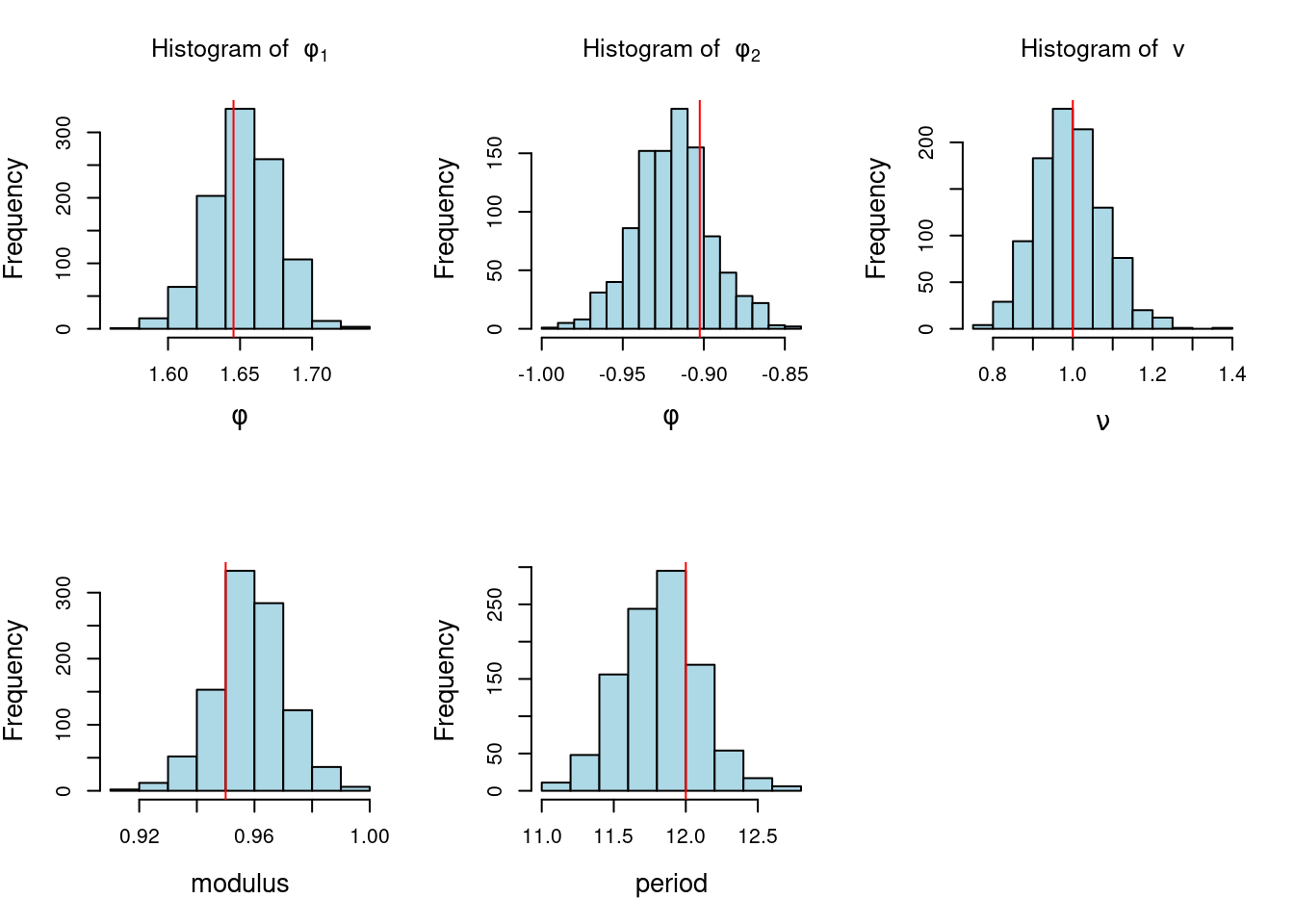

for any t \ge p. The eigenvalues of the matrix G are the reciprocal roots of the characteristic polynomial.

- The eigenvalues can be real-valued or complex-valued.

- If they are Complex-valued the eigenvalues/reciprocal roots appear in conjugate pairs.

Assuming the matrix G has p distinct eigenvalues, we can decompose G into G = E \Lambda E^{-1}, with

\Lambda = \text{diag}(\alpha_1, \dots, \alpha_p),

for a matrix of corresponding eigenvectors E. Then, G^h = E \Lambda^h E^{-1} and we have:

f_t(h) = \sum_{j=1}^{p} c_{tj} \alpha_j^h.

ACF of AR(p)

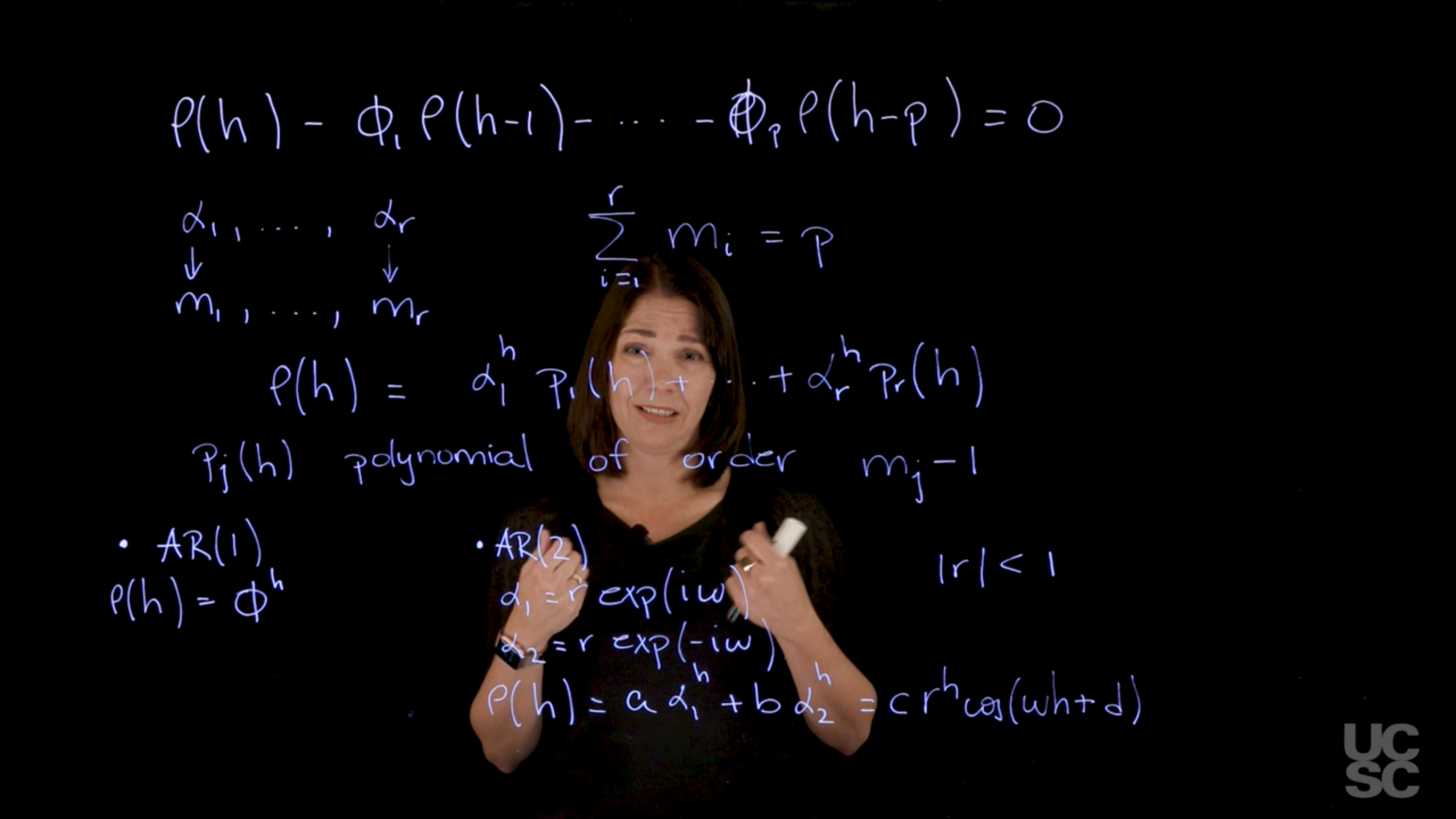

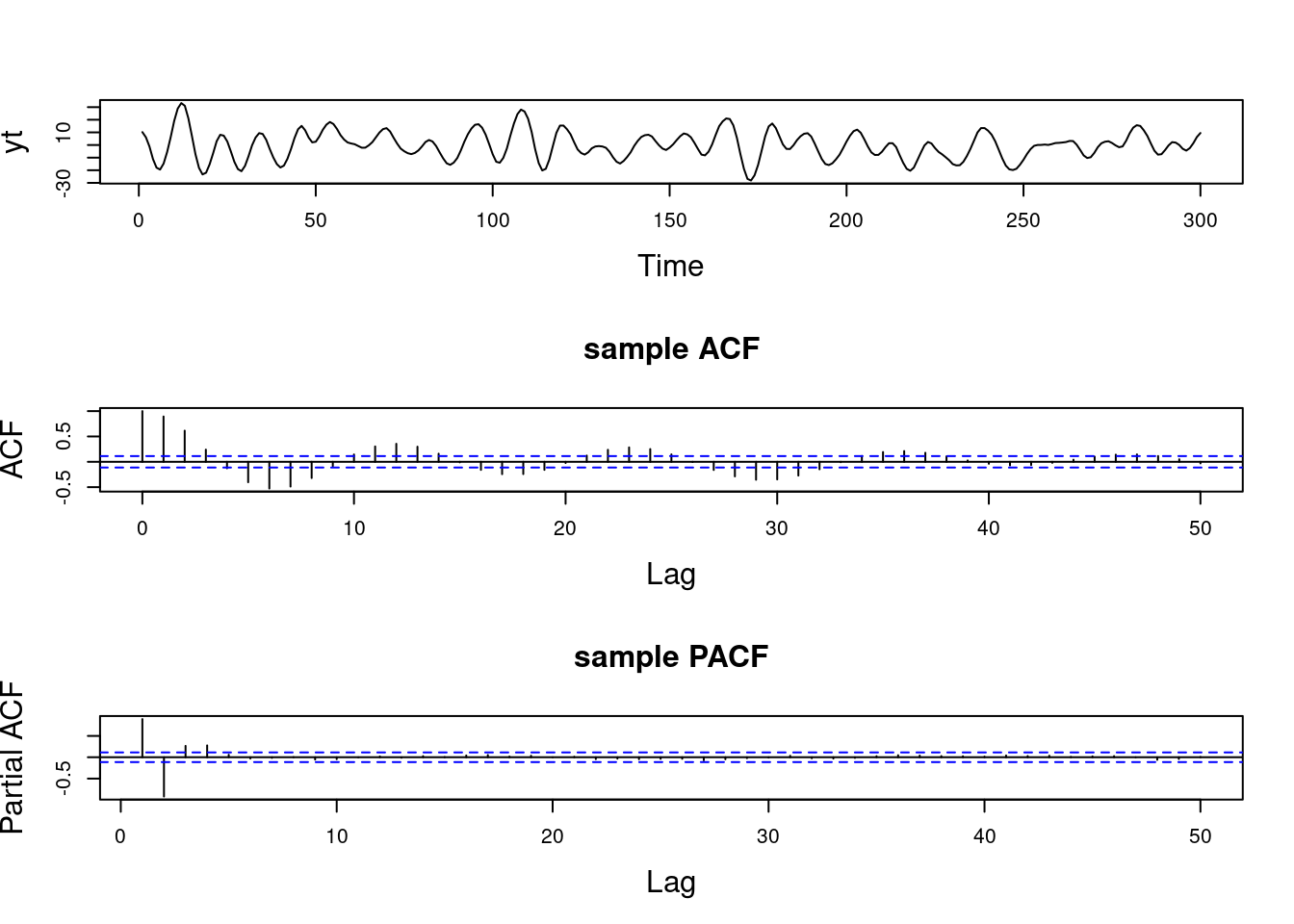

For a general AR(p), the ACF is given in terms of the homogeneous difference equation:

\rho(h) - \phi_1 \rho(h-1) - \ldots - \phi_p \rho(h-p) = 0, \quad h > 0.

Assuming that \alpha_1, \dots, \alpha_r denotes the characteristic reciprocal roots each with multiplicity m_1, \ldots, m_r, respectively, with \sum_{i=1}^{r} m_i = p. Then, the general solution is

\rho(h) = \alpha_1^h p_1(h) + \ldots + \alpha_r^h p_r(h),

with p_j(h) being a polynomial of degree m_j - 1.

Example: AR(1)

We already know that for h \ge 0, \rho(h) = \phi^h. Using the result above, we have

\rho(h) = a \phi^h,

and so to find a, we take \rho(0) = 1 = a \phi^0, hence a = 1.

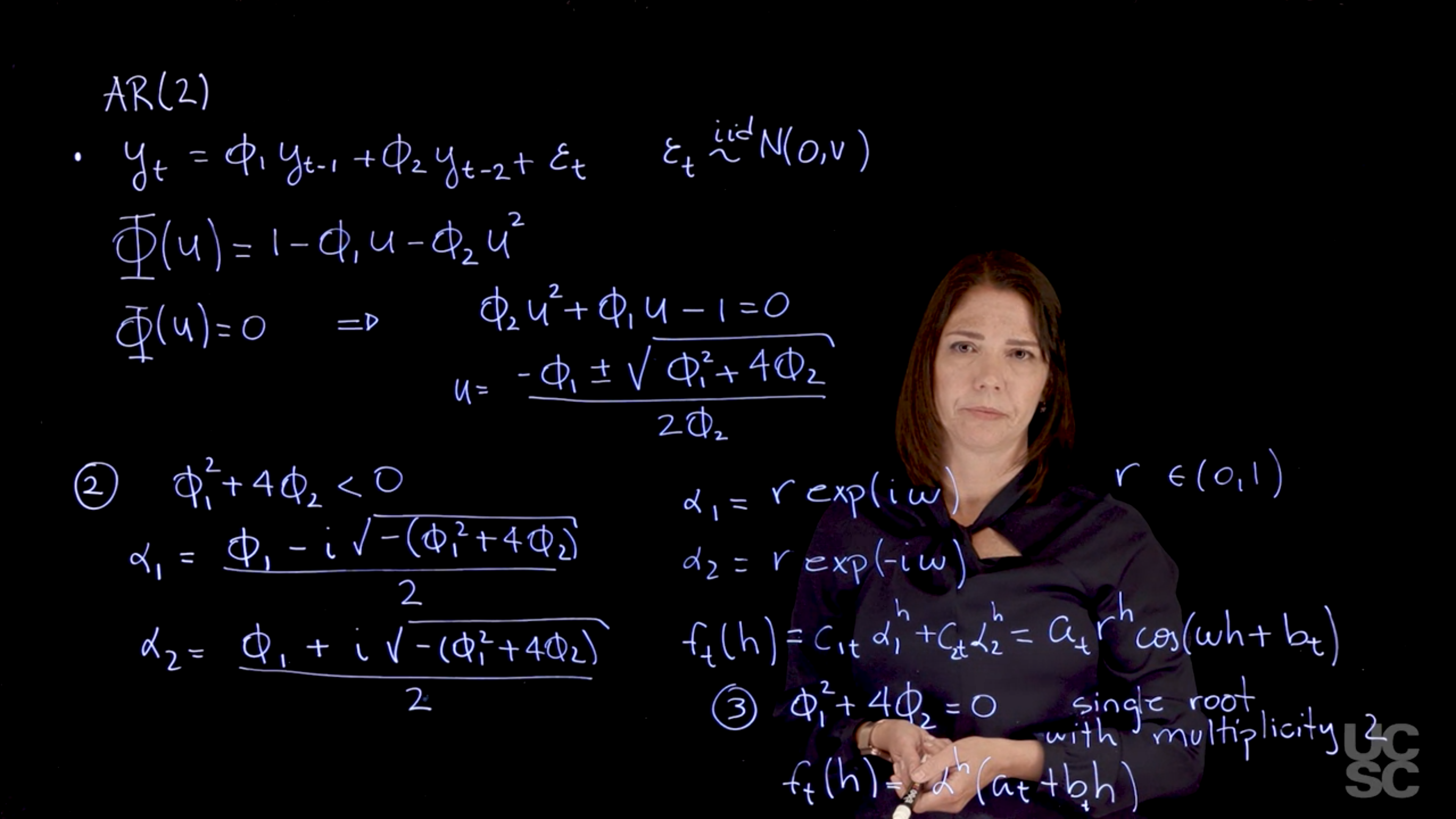

Example: AR(2)

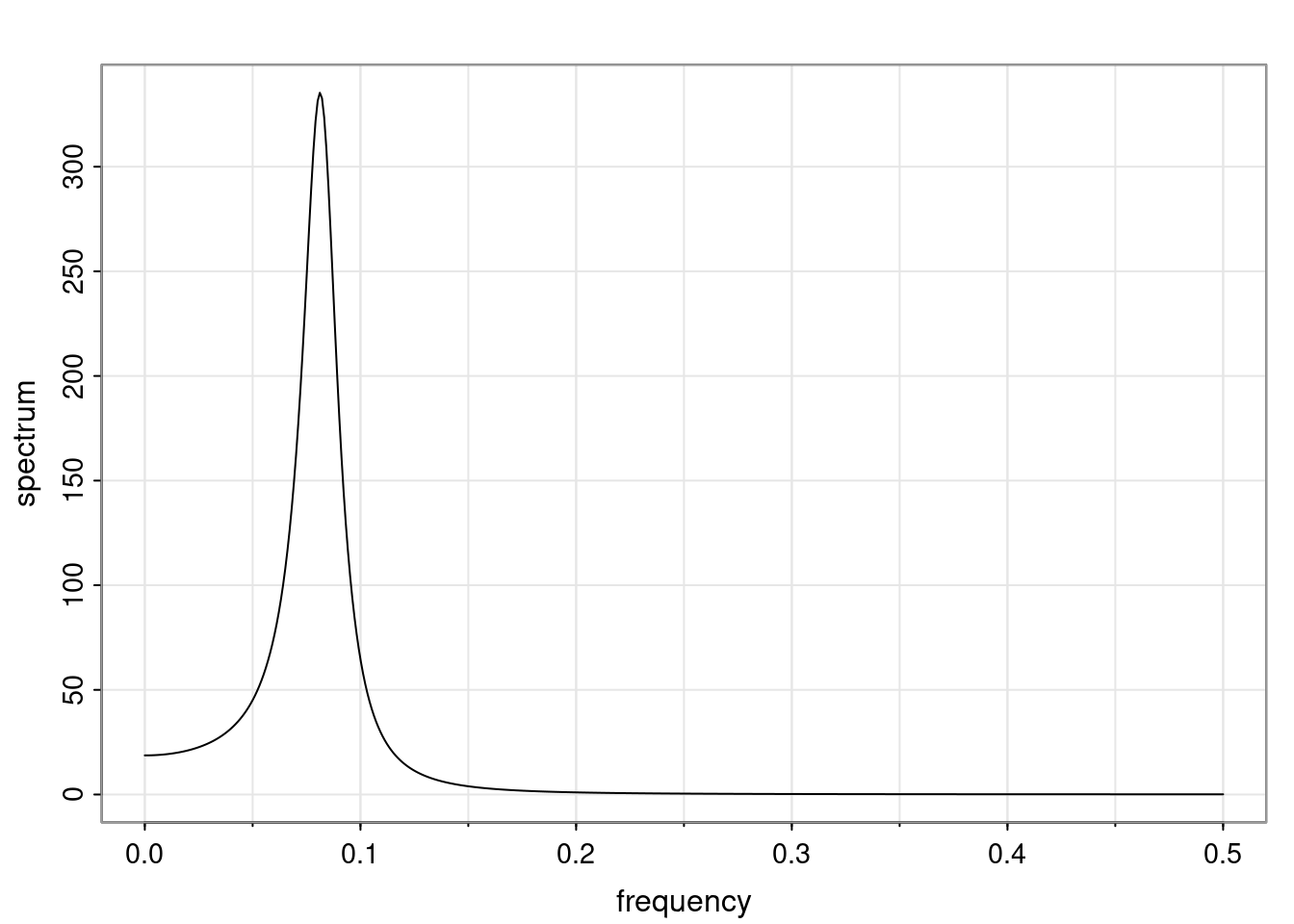

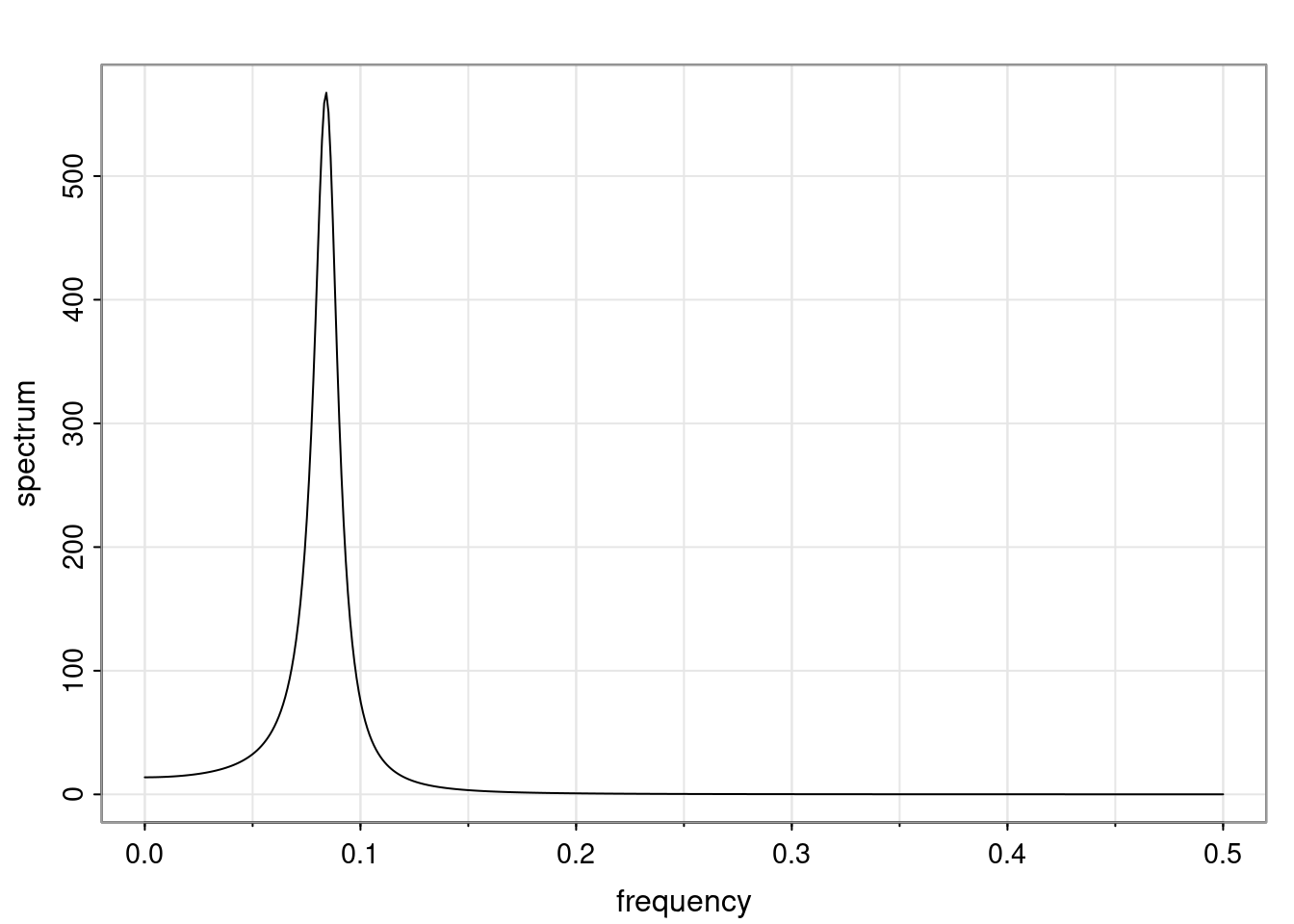

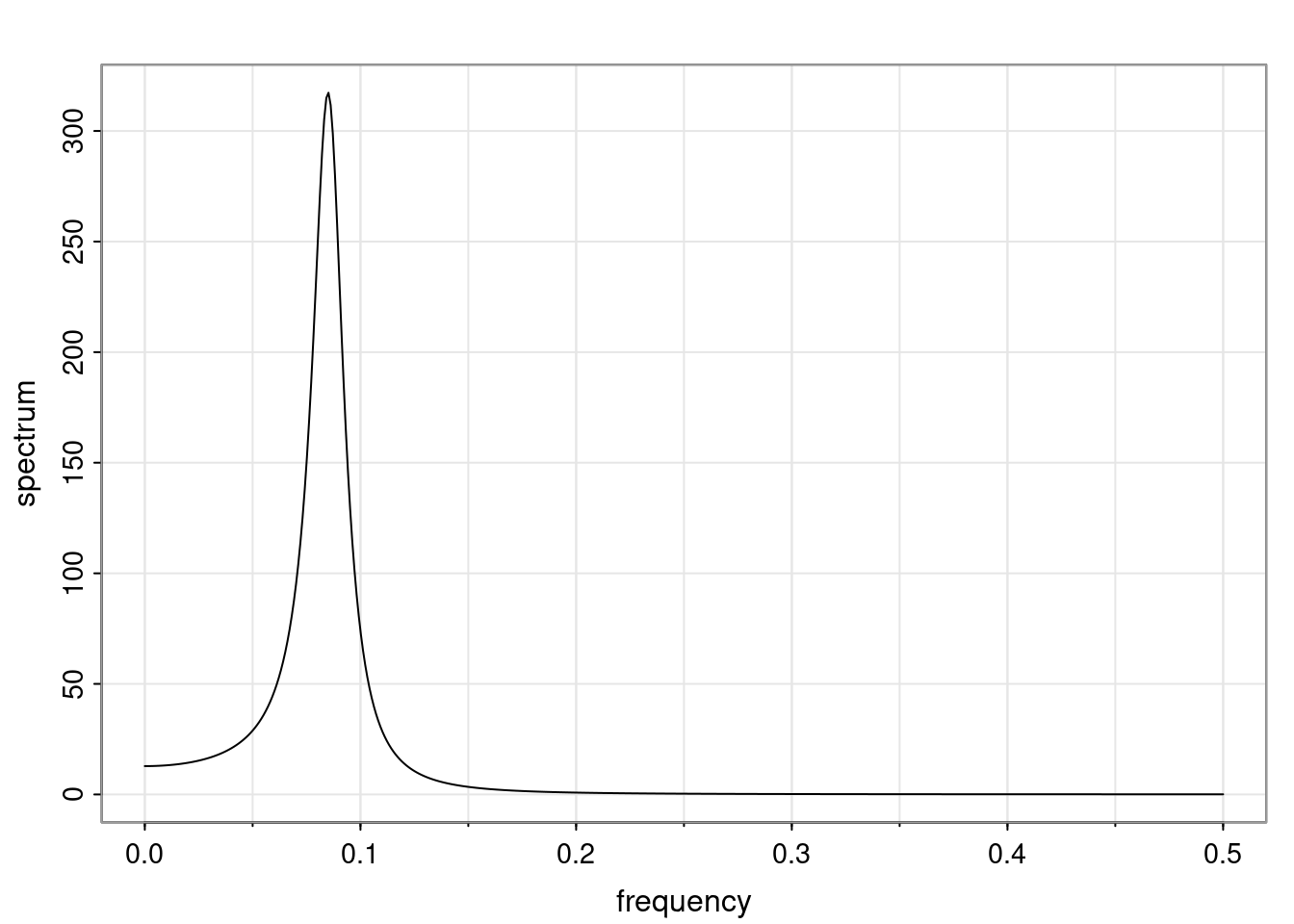

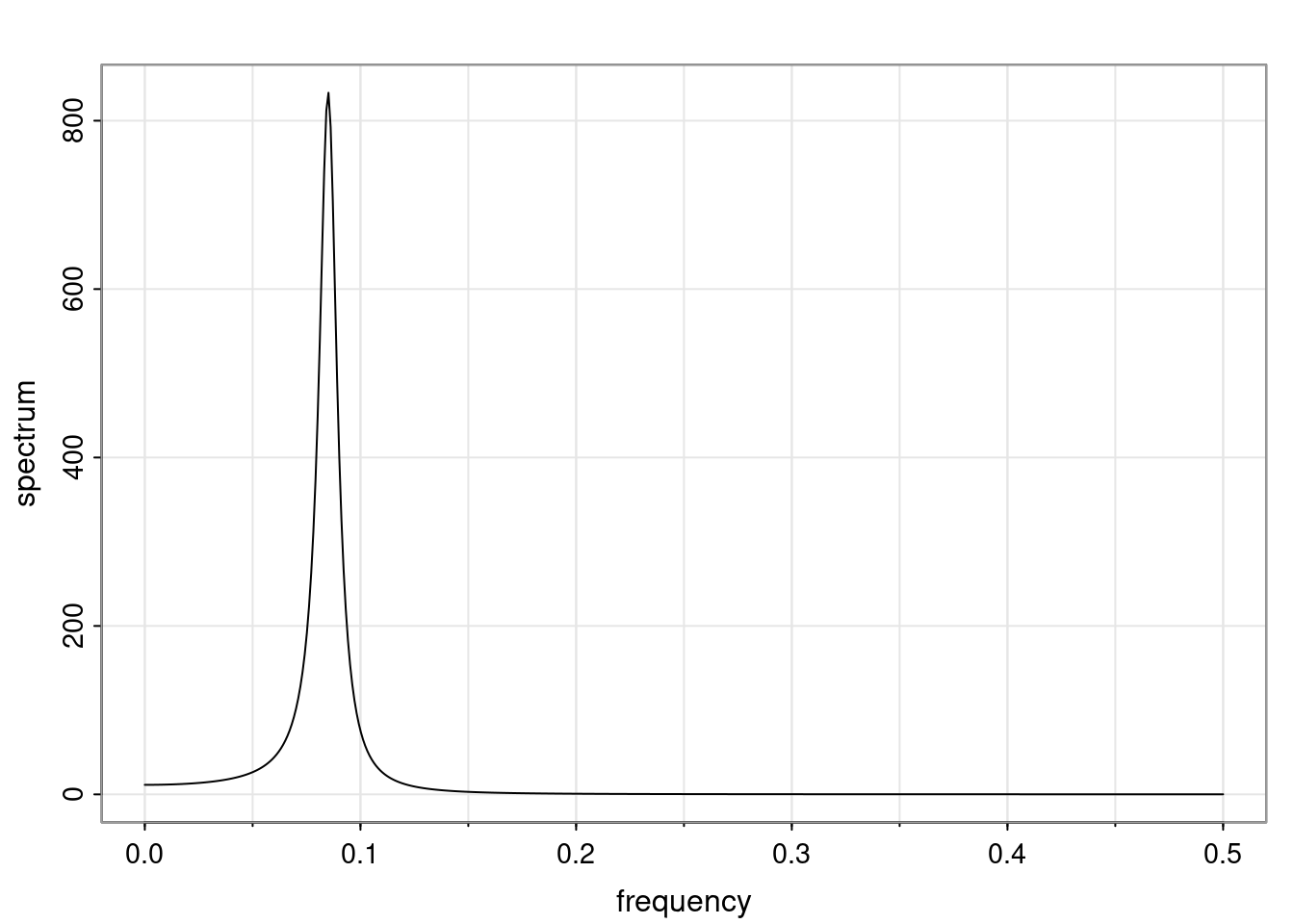

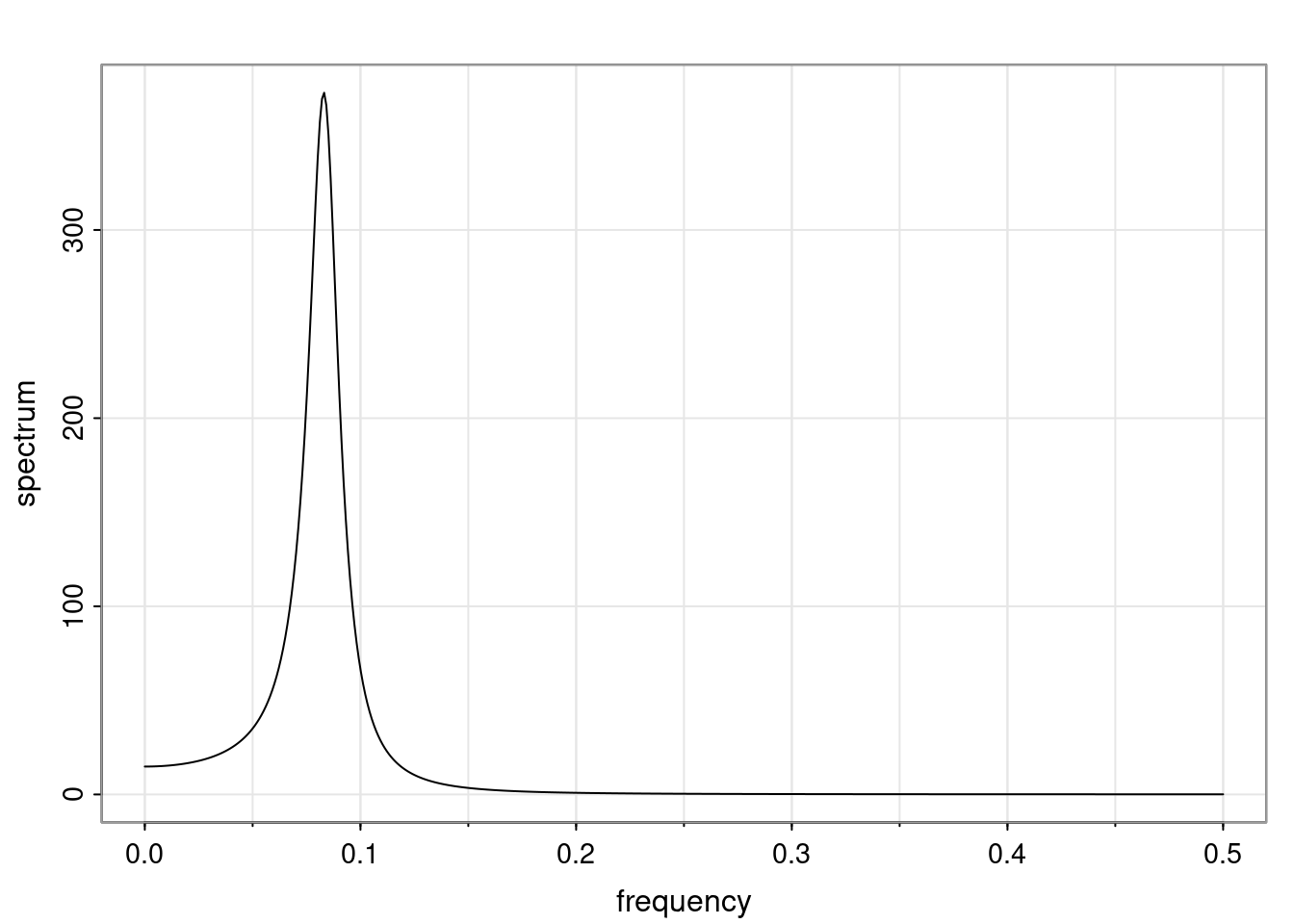

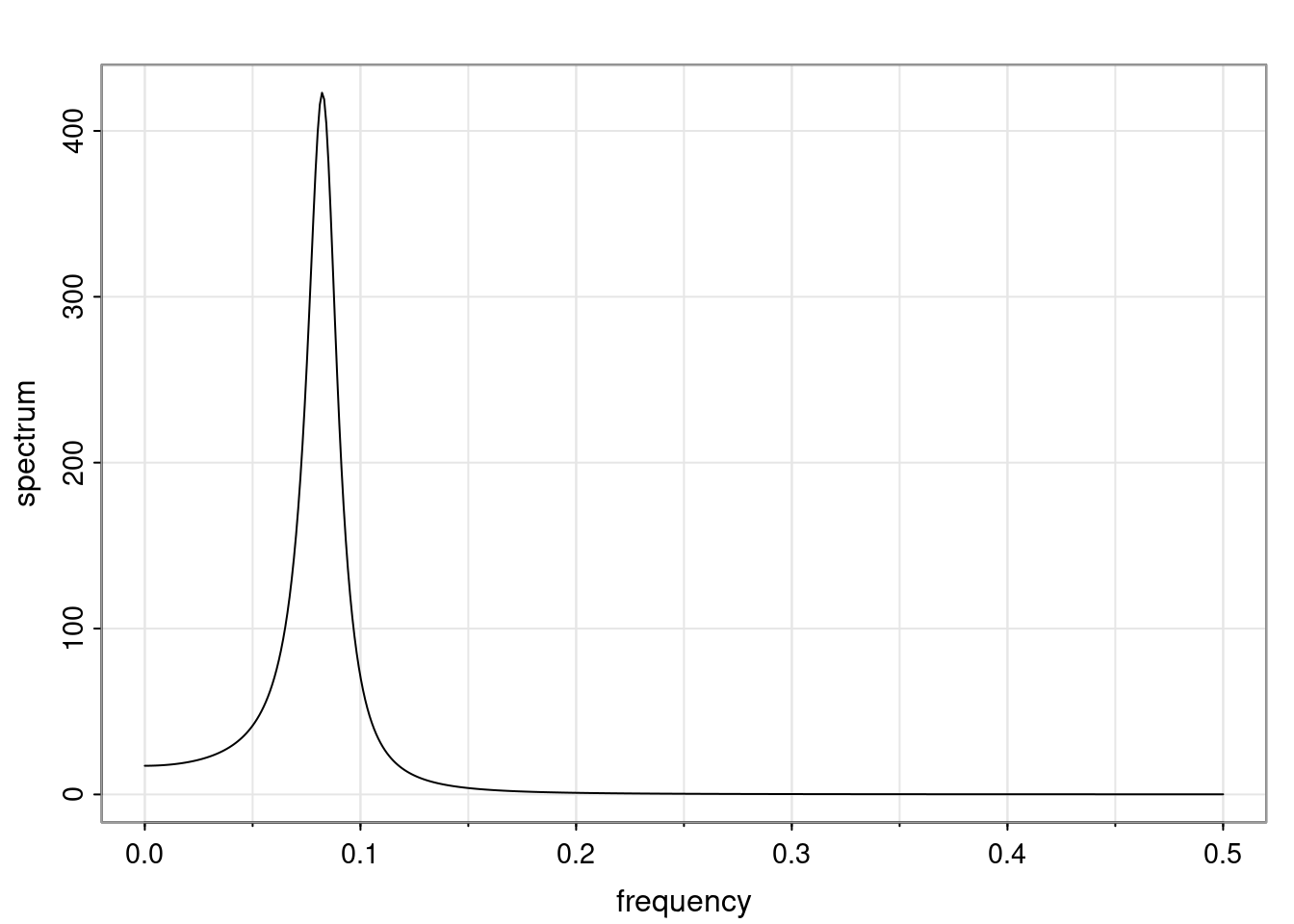

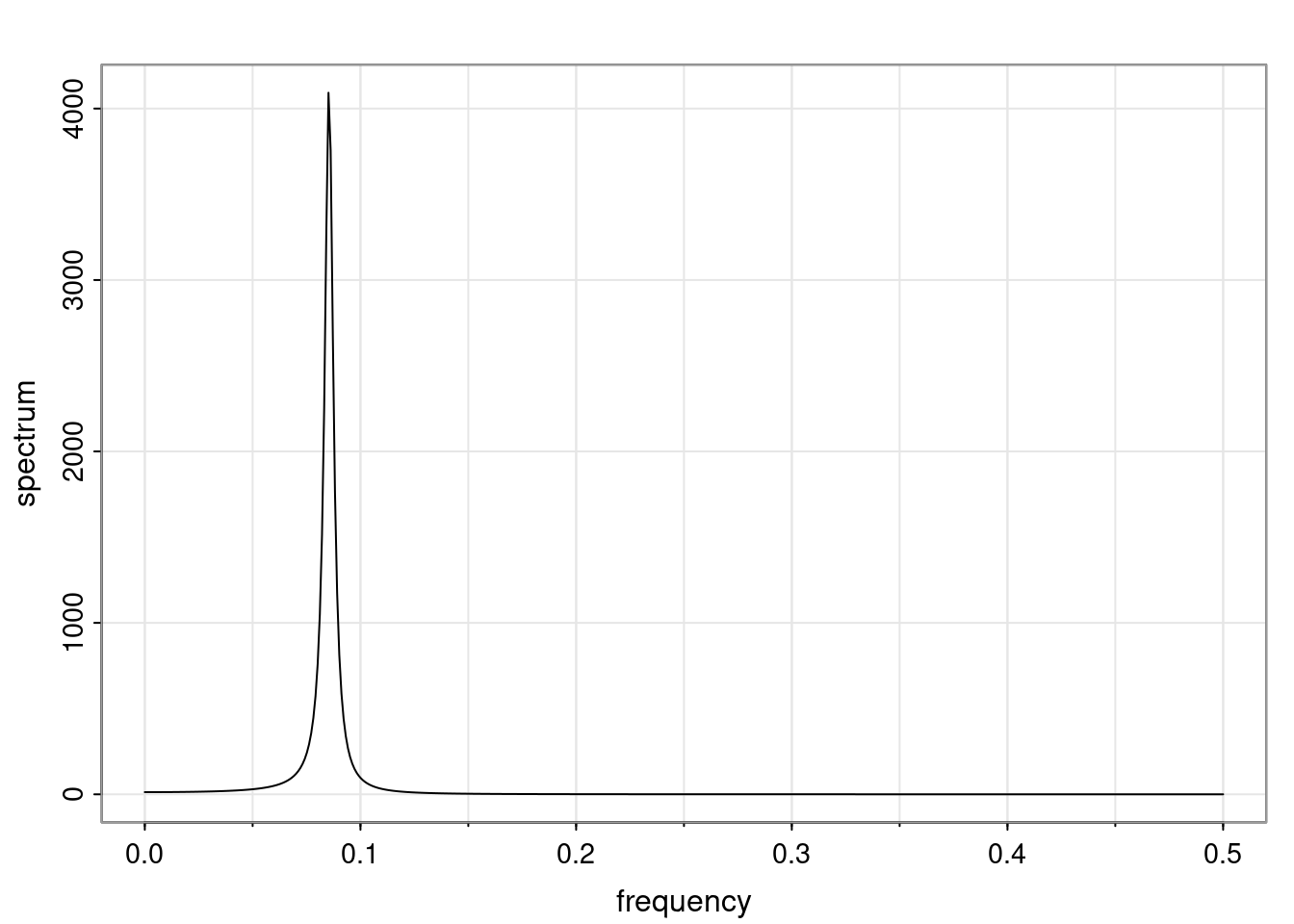

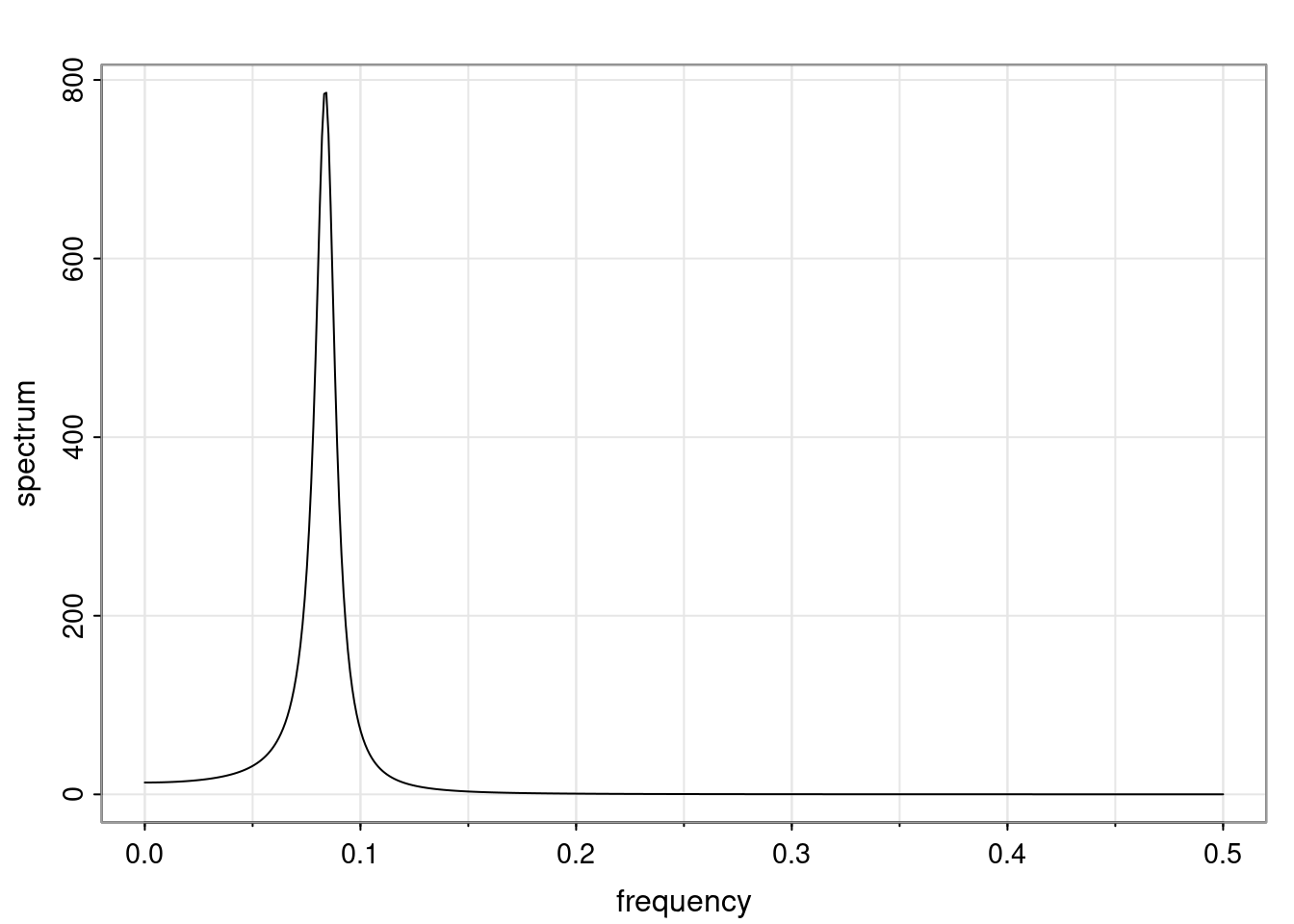

Similarly, using the result above in the case of two complex-valued reciprocal roots, we have

\rho(h) = a \alpha_1^h + b \alpha_2^h = c r^h \cos(\omega h + d).

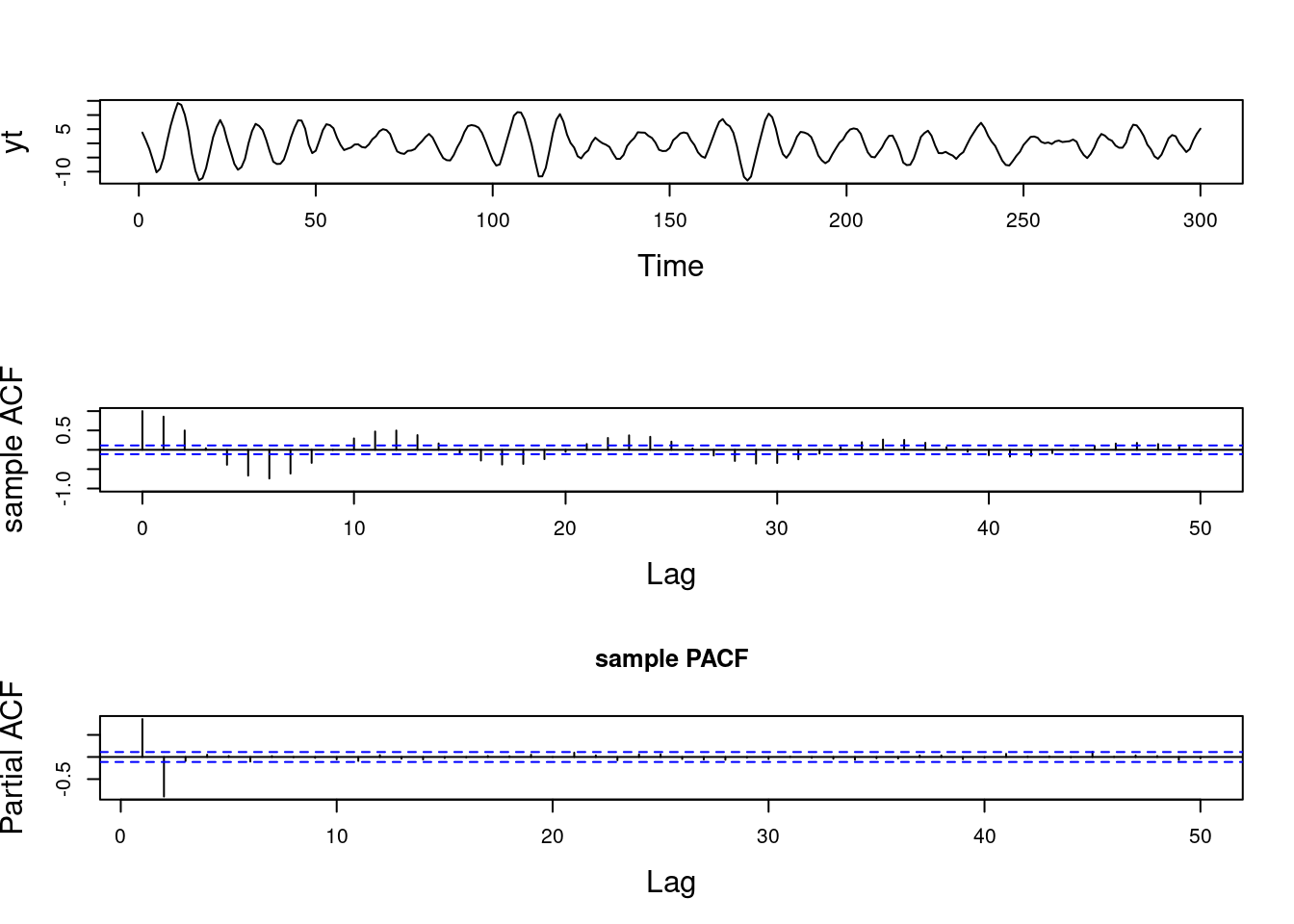

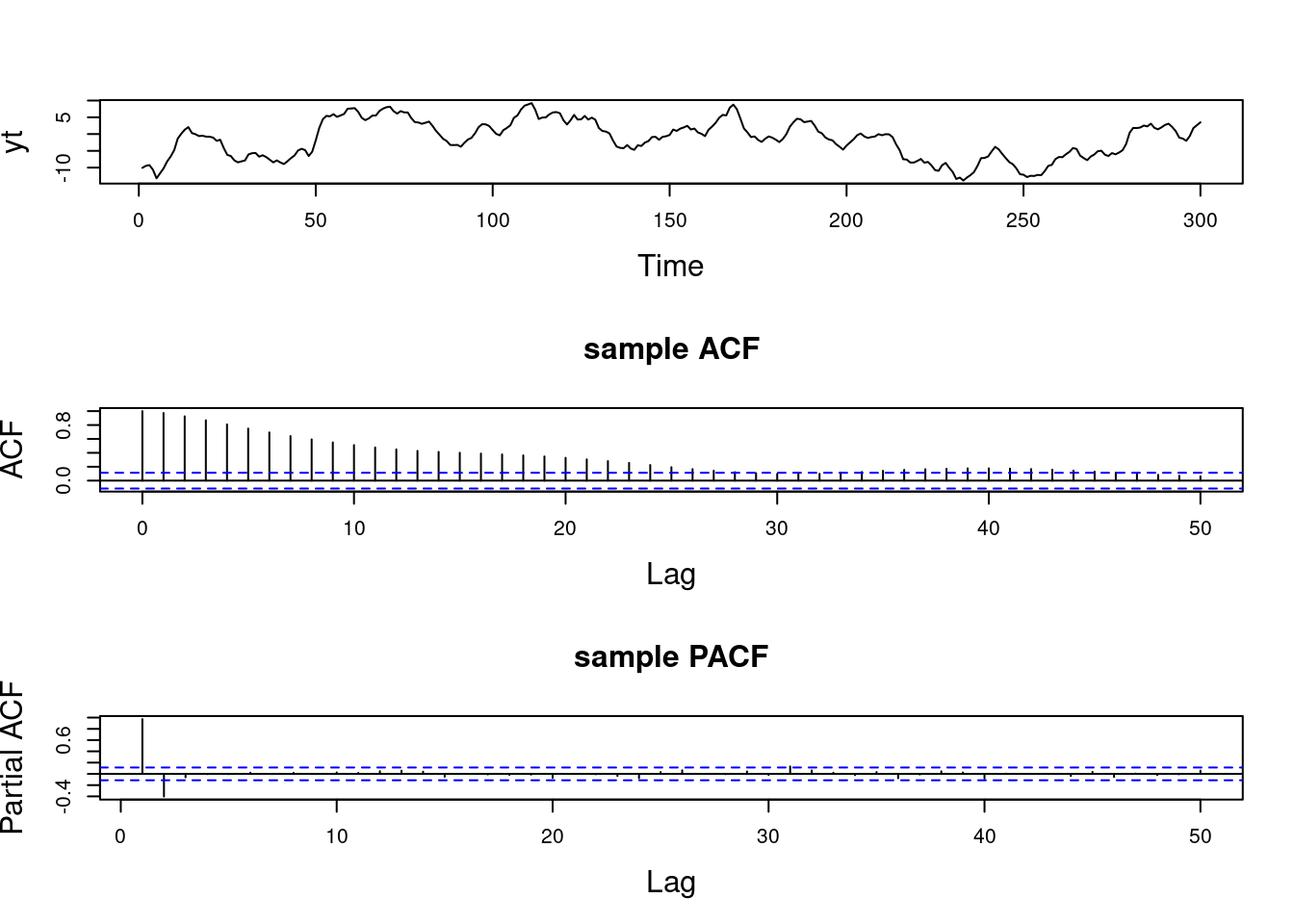

PACF of AR(p)

We can use the Durbin-Levinson recursion to obtain the PACF of an AR(p).

Using the same representation but substituting the true autocovariances and autocorrelations with their sampled versions, we can also obtain the sample PACF.

It is possible to show that the PACF of an AR(p) is equal to zero for h > p.

Quiz: The AR(p) process (Quiz)

Omitted due to Coursera’s Honor Code