This paper considers a setting for the evolution of a complex signaling systems

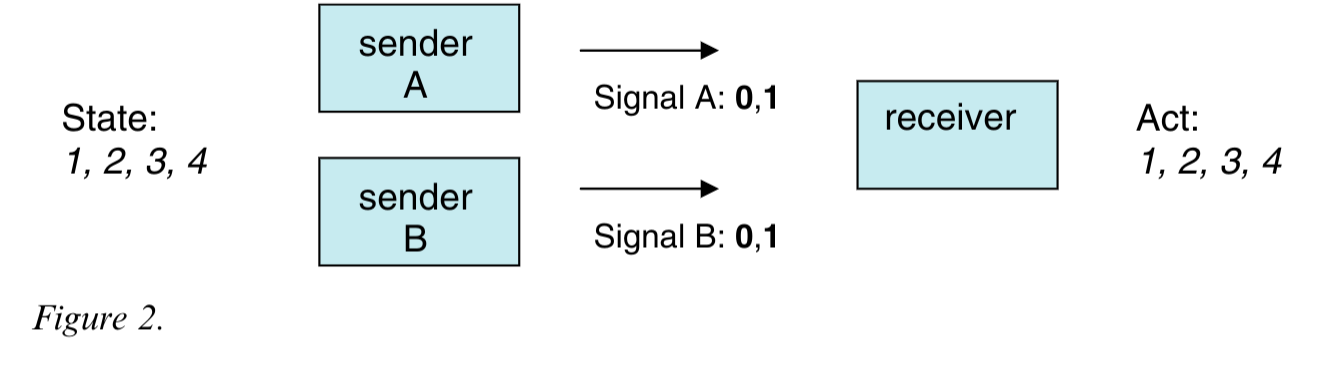

- in this case social evolution or reinforcement learning. As I have already implemented such a system based on Skyrym’s work I was interested in the results. I think this is one of the papers discussed in the book by Skyrms. The main contribution is an extension of the Lewis signaling game of multiple senders that send partial binary signals to the receiver. The receiver aggregates these into a sequence ordered by sender. A complex signaling system is thus learned in which senders spontaneously learn to send a specific partial state.

It may seem surprising that the senders learn to coordinate what part of the state to send even though they start out by picking the signals to send independently of each other.

Abstract

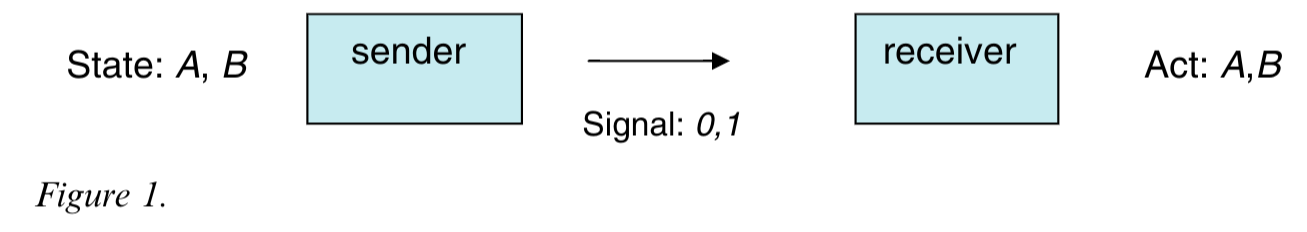

Signaling games with reinforcement learning have been used to model the evolution of term languages ((Lewis 1969); (Skyrms 2010)). In this article, syntactic games, extensions of David Lewis’s original sender–receiver game, are used to illustrate how a language that exploits available syntactic structure might evolve to code for states of the world. The evolution of a language occurs in the context of available vocabulary and syntax—the role played by each component is compared in the context of simple reinforcement learning

– (Barrett 2009)

The Review

First the Lewis signaling game is explained - the game is not presented in terms of game theory e.g. it’s extensive form but using a state transition diagram.

Later lewis signaling variant with two senders is introduced

The paper starts with the standard Lewis signaling game a metric for signaling success a few learning algorithms

- Urn Model after Richard Herrnstein’s matching law and with Rewards := {Succ: +1, Fail:0}

- Urn Model after Richard Herrnstein’s matching law and with Rewards := {Succ: +2, Fail:-1} AKA ARP model

- Bereby-Meyer and Erev 1998 “On learning to become a successful loser”

The Herrnstein’s matching law (Herrnstein 1961) is not a well suited to learning in the signaling system. It is not sample efficient (e.g. it does not learn from making mistakes thus most of the samples are discarded) nor can it escape form the numerous attraction basins of the (partial) pooling equilibria which represent local maxima of expected returns to locate the much rarer global maxima of the separating equilibria that we call signaling systems.

Thus the authors looked for algorithms that could converge faster and also overcome the attraction basins due to local minima of the partial pooling equilibria. Some alternatives listed by Skyrms in (Skyrms 2010) are:

- Thorndike’s law of effect (Thorndike 1927)

- Richard Herrnstein’s matching law (Herrnstein 1961)

- Roth-Erev learning algorithm (Roth and Erev 1995)

- Bush–Mosteller Reinforcement (Bush and Mosteller 1953) Has been shown to correspond the replicator dynamics in the limit of small learning rates.

- Yoella Bereby-Meyer and Ido Erev ARP model (Bereby-Meyer and Erev 1998)

This paper looks at a variant of the Roth-Erev learning which was published in (Bereby-Meyer and Erev 1998) by Bereby-Meyer and Erev titled “On Learning To Become a Successful Loser”. Here the authors consider different abstraction of losses in repeated choice tasks. They use a probability learning task. (basically to estimate p\neq0.5 in a Bernulli trial). They found that by adding constants to the payoff matrix enhanced the learning process and more significantly that learning in the loss domain was faster then in the gain domain.1

1 there are many games where lossess are much more common, also we might not be able to get a signal from a mistake….

Bereby-Meyer and ErevThe paper

To my considerable surprise, Barrett found that Roth–Erev reinforcement learners reliably learned to optimally categorize and signal. — (Skyrms 2010, 140)

In his popular science Classic “The blind watchmaker” (Dawkins 1986), the author, Richard Dawkins, suggest the notion of a blind watchmaker. The idea is that the blind watchmaker does not have to know how to make a watch rather he has to be able to learn by by trial and error how to make better watches. Given the millions of years, evolution’s blind watch maker seems to design wonders with much greater complexity than any watch.

The way I understand this ability to learn to coordinate is

- The senders don’t really learn to coordinate - we have a blind watchmaker at work here….

- Initially Senders don’t really have any meaning in the Lewis signaling game. Only when the environment assign a positive reward (which is a spontaneous symmetry breaking event) due to the a receiver taking the correct action. At this point the senders are bound to send the same signals they each sent before. That is the convention they are learning.

- Assuming they won’t use the same signal combinations again for a different state, this is repeated until all the states and signals are learned.

- There is no reason for the senders to send the same part of the state - they could alternate.

2 signaling systems for a 4 by 4 game

| state | sender 1 | sender 2 | receiver |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0,0 | 0 | 0 | 0,0 |

| 0,1 | 0 | 1 | 0,1 |

| 1,0 | 1 | 0 | 1,1 |

| 1,1 | 1 | 1 | 1,0 |

| state | sender 1 | sender 2 | receiver |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0,1 | 1 | 1 | 0,1 |

| 1,0 | 0 | 0 | 1,1 |

| 0,0 | 0 | 1 | 0,0 |

| 1,1 | 1 | 0 | 1,0 |

For sender 1 and sender 2 any mapping of the signals to state that is one to one works.

However in terms of learnability a system that has a correlated sender sub-state assignment is easier to learn. Is easier to learn because the receiver can learn the mapping of the signals to the state in a single step.

To sum up: senders are assigned a one to one mapping spontaneously whenever the receiver takes the correct action. If they are de correlated with each other or correlated with a sub-state is not important.

However we can see that an arbitrary assignment of the signals to the state is harder to learn. This is because the receiver has to learn the full mapping of the signals to the state. Whereas in the correlated case the receiver can reuse the mapping to generalize.

Note: here we assume that the agents consider the signaling system as mappings rather than a dictionary.

Criticism:

- The new game is not considered from a game theoretic point of view.

- The extensive form should be made clear.

- We don’t have just a new sender - we have seperate information sets for each sender. In RL the senders and the recievers all have different partial information corersponding to a highly localized view of the world.

- Senders don’t see each others signals - as if they must signal at the same time.

- We don’t know if it has similar equilibria as the lewis signaling game.

- We don’t now if there are new kinds of equilibria.

- We don’t know how they are distributed neumerically and this has bearing on the many tables shown in the paper. i.e. do the different empirical rates of success reflect what is expected in term of the relative numbers of equilibria in the game.

- The algorithms used in the paper do not learn to categorically exclude pooling equilibria. So they are slow to converge. Nor do they learn to exclude already solved state action pairs. This makes them slow to converge.

- When the initial distribution of signals is not uniform the agents should do better not worse as they should learn a coding that is more efficient. This notion of coding is mentioned in the paper’s title but we don’t get a satisfying result. Perhaps there is a better way to learn efficient coding for a signaling system.

Two approaches to the signaling system

- sender and receiver create the system spontaneously.

- sender envisions a signaling system, and receiver needs to learn it. There is just one correct signaling system.

- there are many systems and agents coordinate via a beliefs to exclude non-optimal systems.

- this is better because it can handle the case where two groups of agents have learned similar systems and the best common system should emerege.

- case when the sender dies by predation and is replaced by a new sender.

- how do we learn to coordinate without pooling equilibria?

- hint: excluding already solved state action pairs.

- how fast should a data efficient algorithm converge to a signaling system?

- hint: like a coupon collector problem a sum of negative binomials gives O(n log n)

- how can do better?

- as succsses are very rare early on using negative rewards for failure can speed up learning.

- using multiple learners can further improve convergence.

- using source coding should help if the states are not uniformly distributed

- how can we learn the most salient signaling system for an uneven distribution of states possibly changing over time?

- hint: if the urn model is directly learning the mapping this may be hard

- hint: consider an urn scheme that votes via a belief on the most salient signaling system.

- this would let the agents switch between signaling systems as the distribution of states changes. What is the overhead?

- The book by Skyrms suggests that different types of aggregations may lead to different signaling systems. He point out that conjunction is less powerful than concatenation.

- I Found that implementing different aggregation schemes can be challenging - particularly if one has not read this paper! In fact it is hard enough to come up with variants for hard coded aggregation schemes for just the two cases above.

- hint: using a FSM requries coordinating on some matrix of transitions.

- If one thinks of the desiderata for coding schemes - they should be easy to learn, easy to extend, easy to decode, and robust to errors. The easy to decode is also disrable here. I think that aggregation schemes are not very different from coding schemes once we have the ability to handle a sequence of signals.

- Another complexity is that we could consider different settings like in RL. Here if we follow the book, we have

- single sender single receiver (Lewis game)

- multiple senders each with a disjoint partially state and a single receiver (leads to conjunctive aggregations to recover the state)

- constrained binary signal and single receiver (full observability solves the sender decorolated coordination problem - that senders send different parts of the state)

- multiple senders with a fully observed state

- In reality there is a whole zoo of aggregation schemes that are in use in natural languages.

- template based aggregation for template based grammar and morphology (sequence of t signals)

- tree based aggregation leading to recursive structures.

- conjunctive aggregation for logical inference.

- hint operators with noop symbol for closing implied bracket

- sequence with nary operator + > to close the context.

- and ( A, B or C , D ) => and_n A or_n B C > D >

- encoding treess elegently using nary prefix operators

- and ( A, B or C , D ) => and_3 A or2 B C D

- operators take arity as thier first argument like

- and ( A, B or C , D ) => and 3 A or 2 B C D this can implement run length encoding too using

- RLENC arity repetition input+ 0 1 2 3

- and (aaabb aaabb aaabb) => RLENC 3 3 RLENC 3 3 a RLENC 3 2 b

- The issue here is that the aggregation scheme is not learned but fixed. If we were able to also learn an agreagation scheme we might understand how morphology, syntax and many other features of language emerge from a simple aggregation rule.

- How can we learn the most efficient aggregation for a signaling system?

- hint: using a template for the aggregation may be more efficient than learning the aggregation from scratch.

- I Found that implementing different aggregation schemes can be challenging - particularly if one has not read this paper! In fact it is hard enough to come up with variants for hard coded aggregation schemes for just the two cases above.

Citation

@online{bochman2024,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {The {Evolution} of {Coding} in Signaling Games},

date = {2024-06-10},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/reviews/2007/evolution_of_coding/},

langid = {en}

}