- Dialects, Nonnative writing

- Cognates and Borrowing

- Computational Models of Transliteration, Cognates and Borrowing

- Bilingual Embedding, Lexicon Induction (incl. models of cognates)

Introduction

This time we’re going to talk about language contact and change which i think is a you know very interesting and relevant topic if we are going to be thinking about models it’s relevant for a couple reasons one reason is because we’re going to be using lots of cross-lingual transfer approaches in this class another reason is like knowing that language is not like when we talk about english we’re not just talking about you know a single language but we’re talking about a language that’s constantly evolving constantly changing and you know same with any other language is a very important factor of multilingual nlp you know it’s multiple languages even within the same thing that we’re talking about so just to give an example of this from English which presumably everybody knows about I i have a letter from isaac newton from 1672 a letter from wilbur wright who invented the airplane in 1899 in an email from me in 2021 not because I think i’m on the same caliber as any of the other people here but rather from 2021 it was just convenient to get my email but if you look here you can see the letter from isaac newton which says stir to perform my late promise to you I shall without further ceremony acquaint you that in the beginning of the year 1666 at which time I applied my self to the grinding of optic glasses of other figures than spherical I procured me a triangular glass prism to try to there with the celebrated phenomena of colors this is by the way a letter to the editor of the journal so this is what you had to write when you wanted to submit a paper in in 1672. the letter from wilbur wright says dear sirs I have been interested in the problem of mechanical and human flight ever since as a boy I constructed a number of baths of various sizes after the style of Cayley’s and penalties machines my observations since have only convinced me more firmly that human flight is possible and practicable and this is a letter from wilbur wright to the smithsonian asking them for some like materials the final one is my email auto response so much less consequential but you’ll notice actually the letter from overwrite this doesn’t seem so strange it’s like a little bit more formal than we write things nowadays but you know it’s pretty close to the language we speak now it’s also written in a kind of modern typeface similar to corey or new or whatever that you see on your on your computer here from isaac newton it’s pretty different like you know all of the s’s are kind of the old style s that looks like an f you can see that he uses some words that we don’t use very much anymore like there with he also I procured me this isn’t the grammatical form that we really use anymore so you can see that the grammar is actually changing as well oh and actually it’s using another letter that we don’t we don’t use anymore the a a and e combine together so why do languages change if you

Why do languages change

want to learn more about this topic I highly recommend this book why do languages change and it’s pretty amusing it’s about 150 pages so it’s not a heavy read and i’ve learned lots of fun facts about why football is called sorry why soccer is called soccer in english and the name the reason behind the various names of cities in britain and stuff like this but it has this nice categorization in the second chapter that says languages change because of changes in the world so to give an example the way we communicate has changed a lot so I communicate via email as I showed you in the previous slide and so now we have a word

you allbecomingy'allin you know southern southern us dialect and i’m sure you can think of other things in the languages you’re aware of as well another reason is the opposite which is instead of being lazy and abbreviating things away we change things for emphasis or clarity so one of the examples in this book is that in old english the pronouns in in english for he she and they were i’m probably gonna pronounce them completely wrong but hey hill and high or something like that and these are too close together so they were confusable so they you know added additional things onto them to make this more clear and I think some of the people might have read this gibson 2019 survey on how efficiency shapes human language and so basically we have two pressures we want to be lazy we want to say things as efficiently as we can but on the other hand we can’t like say things so efficiently that everything converges into the same pronunciation in the same words because then we couldn’t communicate our thoughts so we have this pressure of making things simpler to make it more efficient and making things more complicated to make it more clear another thing is politeness and as a

Politeness

very interesting example of this politeness we have this google google word list here and this google word list is all of the words that people in google are not allowed to use in documentation or variable names or things like this and just to give some examples you’re not supposed to use well you’re not supposed to use agnostic because agnostic is a name for that’s also used in the us for non-religious and that might affect religious people [Music] another thing i’m assuming this sorry I don’t like you can confirm with google if that’s correct but that’s my guess not supposed to use the word below for some reason maybe it is like indicative of like inferiority or something like this in general you’re not supposed to use words that are indicative of race for example especially if they have a negative or positive connotation cell phone is an americanism so that’s that’s they’re just trying to be more clear and make it so everybody can understand and say mobile phone chubby because that could be derogatory for for people who are like overweight or something so you can see that there’s all these all these things that people like change the way they used to say things for politeness another example is misunderstanding

Misunderstanding

The word bead apparently in english originally meant prayer but it got mistaken because when people are from the catholic faith they they count prayers on little balls and when people heard this they thought bead meant ball instead of prayer so they started using it that way another thing is group identity and prestige this isn’t a really wonderful paper that talks about how people who belong to a certain group in this case forums about beer adopt the way that people speak on that forum and this is something called entrainment it’s a thing where you start adopting the way people speak in order to fit into the group and in this case the group started saying that beer had aroma but then some at some point they started everybody started saying smell maybe an influencer said smell or something like this and then they all switched over to bad so if you’re using the appropriate way of saying things then you know that makes you more cool and so so you do that and another good example of this is actually we were talking about german and how english is a germanic language but actually I don’t know the actual numbers but I think probably half or more of the words in english are from french and the reason why is because you know french people conquered england or much of england at some point and so all of the kind of posh you know like words about government and stuff like that like constitution or election or legislation come from french whereas words like hand and mouth and you know just kind of common everyday words come from german so there was a prestige element with saying things in french so all the kind of higher society words came from french and also structural reasons like if you adopt words from other languages they’re hard to say in that language so you you change them around and stuff like this so basically what I want to point out here is you know language is not static we’re not saying it the same way that we did before but there’s very good reasons why we’re not you know why we’re changing the way we speak I know there was a lot of different things were there any questions about these for comments

Lexical Changes

We also have lexical changes and these can be including things like cognates and lone words that arise from language contact so cognates and loanwords are two varieties of words that are shared across different languages cognates are words that basically start out in a some sort of parent language and and propagate their way into the languages just by you know being used over and over and over again but they change due to the underlying phonetic changes in the language or other factors so this is an example that I gave in the first in the first class but I just posted it here again this is an example of how the word two in english evolved from proto-indo-european. You can see that in english it turned into two in german it’s something like

zweiyou know there are many many other ones and everything else in the indo-european family.One interesting thing is words like q are so frequent that they don’t you know have major changes they don’t get overcome by words in other languages or things like this so basically you know like the more frequent the word is the more likely it is to have descended from some sort of original language and there’s also interesting research not a whole lot of it but on like reconstruction of you know the original pronunciation of the word based on all these different things I see you nodding yes

Loanwords

another example is loanwords so this is just one of my favorite examples the word orchestra originally came from greek it was adopted into the english language just because it’s a cognate you know it was english descended from from the same family as greek but that got adopted into japanese is a loanword and it became orchestra so they changed the pronunciation because you need to change it in order for it to be pronounced pronounceable in japanese and then there was the change in the world in that we we’re not talking about orchestras as much and instead we started having singing machines where it would play music for you and then you would sing and this is called karaoke in japanese where para is an original japanese word that stands for empty and okay is the words from orchestra so it’s basically empty orca and then that got readapted back into english is karaoke so it’s kind of like the okay is from orchestra originally and it came in the circular path here so loanwords you know don’t always have as interesting a story as this but very often they have to do with technology that was invented in that country it got a name in that language and then it gets moved back so the orchestra was invented in europe I got imported to japan and then karaoke was invented in japan and got imported into or well invented in east asia i’m not sure exactly what was invented but got reimported back into the us so like one words very often happen for this precisely this reason it’s to express a concept that wasn’t really around before so it comes back

Language Contact

so if we look at language contact in the lexicon this is a very good introduction of how language contact works and how it’s the major driving factor behind language change and to give just another example of this in addition to the english example to demonstrate that this happens all over the world there’s swahili which is a major language in southeast africa a hundred million speakers and there was a lot of trade between 800 a.d and 1920 and because of this there was a lot of contact between swahili speaking places and arabic speaking places and so there are estimates that say 40 of swahili types are borrowed from arabic largely probably because a lot of the concepts corresponding to these types came together with with trade and this is a very very common this is a very common trend and often it’s a resource-rich donor language that has lots of you know economic influence in the places where the recipient language has received these and basically it goes both directions obviously it’s not just like english to japanese or japanese english it goes in both ways but the amount also you know often tends to be proportional to the number of speakers in the influence

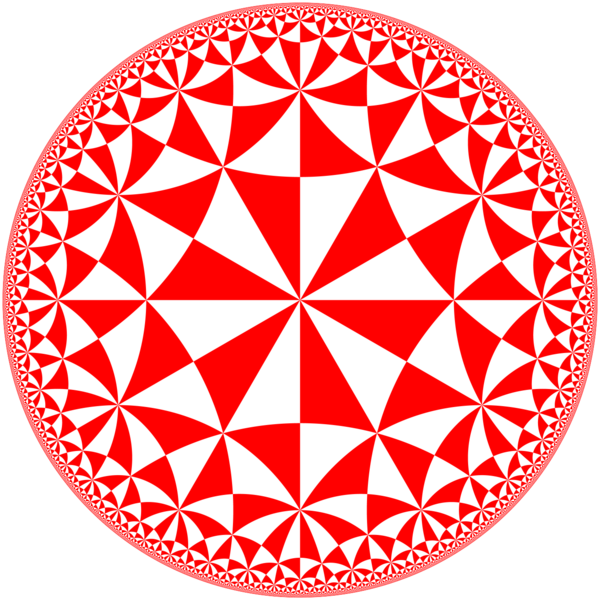

Crosslingual lexical similarities

so because of this there are now cross-lingual lexical similarities where you know one one language borrows words from another language but it changes them to be pronounceable or they change due to evolution and other things like this and so often one thing that you would like to do is you’d like to identify things that are you know equivalent across languages and likely to be mutual translations and this is an example of falafel which I think also was i it was likely adopted into into english I guess from hebrew or arabic perhaps probably hebrew

Stratified lexicon structure

There’s a kind of stratified lexicon structure and the core lexicon is words that originally appeared in the language they’re words that just you know have been here for forever like the word to or the word hand or something like this there’s also or beer or bread there’s also fully assimilated words in for example in english cookie sugar coffee orange other examples would be like election constitution or things like this we don’t even think that they’re loan words and then we have we have partially assimilated words and partially assimilated words are words that could be essentially you can tell that they’re foreign origin based on their like based on just the fact that they haven’t been there for very long like a priori or something like this or deus ex machina or something where it’s like you know you don’t you have a reason to believe that they’re from other languages and then peripheral are kind of things like entities or you know place names or things like this

peripheral vocabulary

Peripheral vocabulary are proper names in specialized terms and very often these will have very similar or exactly the same pronunciation across many different languages borrowing they might be similar they might have similar spelling and then you have content words in the in the core lexicon like like night from one ancestral language

lexicon induction

In order to to take advantage of this one thing that you can do is cross-lingual lexicon induction and basically what this is is this is identifying words that mean the same thing across different languages and of course this is this is easier if they’re words of similar origin because if they are then the spelling could be the same the pronunciation could be the same this could give you hints about how which words correspond to each other so lexicon induction the task itself is basically in a way a classification task where you’re given a word in a language like this arabic word here and you have a very large number of words in the in the lexicon from the other language like hebrew and you try to pick which one is the correct translation here so this is obviously a hard task because you know any classification problem with like 100k way classification problem is going to be difficult but you can take advantage of these kind of structural similarities to do a good job of this

Transliteration

so for peripheral things especially proper names or things where we can assume that the spelling is similar there are models of transliteration and transliteration is essentially a a problem of taking in a word in one language and trying to output the word in the other language knowing that the only thing that differs between them is the pronunciation so this would be an example like new york where this is translated basically pronunciation by pronunciation into the other one into the other language and there’s lots of models for this early models for this used finite state transducers there’s also lstms with attention or you know just using a regular sequence sequence model to solve this but in addition to this one of the features of transliteration is that transliteration tends to be done monotonically so the input and the output tend to be in the same in the same order so there’s also models that take explicit like advantage of this so yeah this is this is one one task that you can do with respect to cross-linkable lexicon cross-lingual lexical learning there’s with respect to like if you think transliteration is interesting oh sorry i forgot one one important thing so just because something’s an entity doesn’t mean it’s just a transliteration problem doesn’t mean that like the only thing you need to do is map the pronunciation so just to give an example carnegie mellon university if you think about it in your language i think it’s probably likely that you don’t just pronounce university unless university in your language is also pronounced similarly to university like for example in in japanese that would be hanagi meron where carnegie mellon is transliterated but daigaku is the japanese version of university so because of this named entity translation is not just transliteration it’s a mix of transliteration and translation that being said there are shared tasks on named entity transliteration and you can do things like measuring word accuracy in the top one measure like the f score of words in the top one or you can treat it as a transliteration mining task where you have entities in one language and a huge list of entities in the other language and see how well you can identify entities there and there’s also downstream evaluations and things like empty and information extraction as well so also relatively recently there was this paper presented on a large-scale name transliteration resource with 1.6 million named entities across 180 languages so if you’re interested in entities or entity linking or any anything with regards to this you can take a look at this paper here

Cognate loan words

Next we have cognates and loan words and cognates and loanwords are the ones that I talked about before and one of the interesting things about this is there’s a lot of different factors that go into what actually happens when you borrow a word and here are two examples from the previous arabic or sorry three examples from the previous arabic and swahili example but you can have things like adopting the syllable structure to be appropriate for the for the language degemination so swahili doesn’t allow consonant clusters so it removes consonant cluster and vowel substitution because certain vowels are more natural here you can also modify the morphology apply morphology from the target language and other things like this or adapt consonants appropriately so what you can see is basically this is assimilating the word into the language to make it seem like natural pronunciation in the language so there’s a huge amount of linguistic

lexical borrowing

resource research on lexical borrowing like case studies of lexical borrowing across language pairs what kinds of phonological morphological phenomena happened in borrowing case studies of socio-linguistic phenomena and borrowing like what what words tend to be borrowed what words tend to not be borrowed etc

cognates

There’s a fairly large number of like cognate in loanword models that do things like phonologically weighted levenshtein distance so basically this waits likely to happen phonological substitutions to upgrade ones that are more likely like you might swap a vowel into a vowel but not a consonant into a vowel and other other things like the ones that I listed below and there’s also similar

cognate databases

cognate databases across 338 languages 3.1 million cognate pairs and 35 writing systems so if you’re interested in in studying more about this you can do this too and there’s also a lexical

lexical databases

borrowing database world load word database so i’m not gonna go into a whole lot unsupervised lexicon induction of detail about this here but there’s also unsupervised models of lexicon induction and basically the the way that most of these models work now is they work either as an unsupervised task of identifying lexicon items like I talked about before you know given a certain word what are all the what is the word in the other language that corresponds to this word and in the unsupervised setting what you do is you learn monolingual embeddings first and these monolingual embeddings basically capture the the either spelling or distributional characteristics of each of the words you then find an alignment between the embedding spaces by like rotating one of the two embedding spaces to match the other one using a distributional similarity between the the two aligned embedding spaces you find nearest neighbors to induce a lexicon and you perform supervised alignment to minimize the distance between lexical items further so it’s kind of an iterative process where you start out with an unsupervised objective identify a few pairs with high confidence and then provide propose sorry then perform supervised alignment and there’s a very nice extensive survey of different methods that you can use to do this here if if this is of more interest so basically the this is a method that’s used to obtain bilingual dictionaries that you can then use for downstream tasks as well cool so basically that that’s all I have for the lecture part for today and I talked a little bit about language contact language change and how this affects the lexicon are there any questions before we go into the discussion part

assimilated

it’s something that like obviously english speakers you know recognizes something that didn’t originate in english like if you ask anybody they they would know and so I think that would say that’s basically partially assimilated you know a lot of a lot of people know what lasse fear means but they would recognize that something something foreign I guess

lifeschool

That’s a really good question and I i think basically the knowing about these things could lead you to be able to create better applications so if you think about the if you think about the simplest possible way to have any sort of like life school sharing between languages it’s train a model on lots of different languages and hope that something good happens and that’s actually what we do right now a lot of the times so we have like a character based model or a subword based model and we train it on lots of different languages or we train it and then we do alignment here and I think actually a lot of the stuff that I presented here was more forward-looking in that it’s like this is the way that lexical sharing actually happens in language and there’s not a whole lot of work that actually applies it in an intelligent way to doing these things one example that I i can give is this is a paper where we used explicit morphological and phonological embeddings to try to like do better information sharing between languages this was back when we just used like word to back embeddings or things like this it wasn’t when we used bert or or other things here so I think you know similar language similar methods like this could be applied to learning like multilingual birds or multilingual machine translation models or something like that as well so yeah

Outline

- Introduction: Language Contact and Change

- Language is Dynamic: Languages are always evolving, not static. Examples from Isaac Newton’s letter (1672) compared to Wilbur Wright’s (1899) and modern email illustrate language change over time.

- Relevance to Multilingual NLP: Multilingual NLP must consider language evolution, especially with cross-lingual transfer approaches.

- Why Languages Change

- Changes in the World:

- New technologies and concepts lead to new words (e.g., “email”).

- Obsolete terms disappear (e.g., “radiogram”).

- Laziness/Efficiency:

- Words are shortened for efficiency (e.g., “telephone” to “phone”).

- Emphasis/Clarity:

- Changes to avoid confusion, like pronoun shifts (e.g., “he/heo/hi” to “he/she/they”).

- Politeness:

- Avoiding offensive or culturally insensitive language (e.g., Google’s word list).

- Misunderstanding:

- Word meanings change due to misinterpretation (e.g., “bead” from “prayer” to “small ball”).

- Group Identity/Prestige:

- Adopting language to fit in or sound sophisticated (e.g., aroma -> smell). French influence in English, where posh words like “constitution” come from French.

- Structural Reasons:

- Adapting words to fit the phonetic and morphological rules of a language.

- Changes in the World:

- Lexical Changes

- Cognates: Words with a shared ancestor, evolving from a parent language. Example: “Two” in English and “zwei” in German.

- Loanwords: Words adopted from another language. Example: “Orchestra” from Greek to Japanese (オーケストラ), then adapted to “karaoke”.

- Language Contact and the Lexicon

- Definition: Language contact is the use of multiple languages in the same place at the same time.

- Driving Force: Language contact is a major driver of language change.

- Case Study: Arabic-Swahili

- Historical Context: Trade between 800-1920 AD led to significant language contact.

- Influence: Approximately 40% of Swahili words are borrowed from Arabic.

- Lexical Borrowing

- Pervasiveness: Common in languages, especially from resource-rich or socially influential ones.

- Cross-Lingual Lexical Similarities

- Bridging Languages: Identifying orthographically or phonetically similar words across languages that are likely mutual translations.

- Lexicon Structure

- Core: Basic, frequently used words (e.g., beer, bread).

- Assimilated: Integrated loanwords (e.g., cookie, sugar, coffee, orange).

- Peripheral: Proper nouns and specialized terms (e.g., New York, Luxembourg).

- Cross-Lingual Lexical Learning

- Cross-Lingual Lexicon Induction: Identifying word meanings across languages.

- Transliteration Models

- Models: Finite State Transducers (FSTs), LSTMs with attention.

- Evaluation: Word accuracy, F-score, ranking metrics like Mean Reciprocal Rank (MRR).

- Resources: Databases of named entities.

- Cognates and Loanwords: Adaptation

- Phonological and Morphological Integration:

- Syllable structure adaptation.

- Consonant cluster removal (degemination).

- Vowel substitution.

- Application of target language morphology.

- Consonant adaptation.

- Examples (Arabic-Swahili): Adaptation of words like “minister” and “palace”.

- Phonological and Morphological Integration:

- Linguistic Research on Lexical Borrowing

- Case studies in language pairs (e.g., Cantonese, Korean).

- Phonological, morphological, and syntactic integration.

- Sociolinguistic phenomena in borrowing.

- Cognate and Loanword Models

- Phonologically-weighted Levenshtein distance.

- Phonetic and semantic distance.

- Generative models of sound laws and word evolution.

- Optimality-theoretic constraint-based learning.

- Cognate and Lexical Borrowing Databases

- Cognate databases with millions of cognate pairs across many languages.

- Lexical borrowing databases like the World Loanword Database.

- Bilingual Lexicon Induction

- Steps:

- Learn monolingual embeddings.

- Align embedding spaces.

- Find nearest neighbors to induce lexicon.

- Perform supervised alignment to minimize distance between lexicon items.

- Steps:

- Discussion Points

- How knowledge of lexical sharing can improve applications.

- Examples of using morphological and phonological embeddings for information sharing between languages.

- Discussion options:

- Efficiency in language.

- Historical influences and loanwords in specific languages.

Papers

- Gibson 2019: Survey on how efficiency shapes human language.

- Danescu-Niculescu-Mizil et al. 2013: Paper about group identity and prestige.

- Itô & Mester ’95: Work on core-periphery lexicon structure.

- Knight & Graehl ’98: Work on FSTs for transliteration models.

- Rosca & Breuel’16: Work on LSTMs with attention for transliteration models.

- Wu & Cotterell’19: Work on exact hard monotonic attention for character-level transduction.

- Mann & Yarowsky ’01, Dellert ’18: Phonologically-weighted Levenshtein distance between phonetic sequences.

- Kondrak ’01, Kondrak, Marcu & Knight ’03: Phonetic + semantic distance.

- Bouchard-Côté et al. ’09: Log-linear model with Optimality-theoretic features.

- Hall & Klein ’10, ’11: Generative models of sound laws and word evolution for cognate identification.

- Tsvetkov & Dyer ’16: Optimality-theoretic constraint-based learning for loanword identification.

- Soisalon-Soininen & Granroth-Wilding ’19: Cognate identification using Siamese networks.

- Yip ’93, Kang ’03, Kenstowicz & Suchato ’06, Benson ’59, Friesner ’09, Schwarzwald ’98, Ojo ’77, Schadeberg ’09, Johnson ’14, Haspelmath & Tadmor ’09: Case studies of lexical borrowing in language pairs.

- Holden ’76, Van Coetsem ’88, Ahn & Iverson ’04, Kawahara ’08, Hock & Joseph ’09, Calabrese & Wetzels ’09, Kang ’11; Rabeno ’97, Repetti ’06; Whitney ’81, Moravcsik ’78, Myers-Scotton ’02: Case studies of phonological/morphological phenomena in borrowing.

- Guy ’90, McMahon ’94, Sankoff ’02, Appel & Muysken ’05: Case studies of sociolinguistic phenomena in borrowing.

Additionally, the lecture mentions a paper that uses explicit morphological and phonological embeddings to improve information sharing between languages. There is also a paper presented on a large-scale name transliteration resource with 1.6 million named entities across 180 languages.

Citation

@online{bochman2022,

author = {Bochman, Oren},

title = {Language {Contact} and {Change}},

date = {2022-02-10},

url = {https://orenbochman.github.io/notes-nlp/notes/cs11-737/cs11-737-w08-contact/},

langid = {en}

}